Did that title make some of you cringe? Curl into a little ball and whimper? Dash screaming from the room?

That’s right, folks: it’s once again time for my yearly foray into the mysteries of synopsis-writing. You didn’t think I was going to let you send off those query letters you’ve just perfected with just a so-so synopsis, did you?

I’m kind of excited to be exploring the subject again, to tell you the truth. Having recently had to produce several synopses on a tight deadline myself — yes, Virginia: unlike query letters, agented writers still have to produce synopses on a regular basis — I’m fresh from that oh, God, how can I possibly give any sense of my book in so short a space? feeling this time around. So I’ve been overhauling my classic advice on the subject, fine-tuning it so what I say is in fact what I do.

Before I launch into the resulting avalanche of insights, however, I want to give you all a heads-up about some alternate reading material that might help everyone understand the culture within which synopses, queries, and manuscript submissions tend to be read.

A bit surprised? I don’t blame you; this is sort of out of character for me. As the proprietor of a self-consciously practical blog on all things writerly, I seldom use this space to urge my readers to click elsewhere and read any of the many articles out there about the state of the publishing business. I assume, perhaps wrongly, that most of my readers don’t come to Author! Author! primarily because they a little extra time to kill: as those of you who stuck with me through my recent How to Write a Really Good Query Letter series, I tend to operate on the proposition that we’re all here to work.

Not that we don’t have a quite a bit of lighthearted fun on the way, of course. But I figure that those of you deeply interested in the dire predictions that keep cropping up about the future of books can track them down on your own. (As, I must admit, I do on a regular basis.)

Today, I’m going to make an exception. In the last week or so, a couple of really informative essays have popped up on the web. The first, a series of observations in the Barnes & Noble Review about, you guessed it, the state of modern publishing, is by former Random House executive editor-in-chief Daniel Menaker. I think it’s essential reading for any aspiring writer — or published one, for that matter — seeking to understand why getting a good book published isn’t as simple as just writing and submitting it.

In the midst of some jaw-dropping statements like, “Genuine literary discernment is often a liability in editors,” Menaker gives a particularly strong explanation for why, contrary to prevailing writerly rumor, editors expect the books they acquire not to require much editing, raising the submission bar to the point that some agency websites now suggest in their guidelines that queriers have their books freelance-edited before even beginning to look for an agent. Quoth Mssr. Menaker:

The sheer book-length nature of books combined with the seemingly inexorable reductions in editorial staffs and the number of submissions most editors receive, to say nothing of the welter of non-editorial tasks that most editors have to perform, including holding the hands of intensely self-absorbed and insecure writers, fielding frequently irate calls from agents, attending endless and vapid and ritualistic meetings, having one largely empty ceremonial lunch after another, supplementing publicity efforts, writing or revising flap copy, ditto catalog copy, refereeing jacket-design disputes, and so on — all these conditions taken together make the job of a trade-book acquisitions editor these days fundamentally impossible. The shrift given to actual close and considered editing almost has to be short and is growing shorter, another very old and evergreen publishing story but truer now than ever before. (Speaking of shortness, the attention-distraction of the Internet and the intrusion of work into everyday life, by means of electronic devices, appear to me to have worked, maybe on a subliminal level, to reduce the length of the average trade hardcover book.)?

That’s a mouthful, isn’t it? Which made your stomach knot tighter, the bit about book length or that slap about writers’ insecurities?

It’s a bit of a depressing read, admittedly, but I cannot emphasize enough how essential it is to a career writer’s long-term happiness to gain a realistic conception of how the publishing industry works. Since rejection feels so personal, it can be hard for an isolated writer to differentiate between rebuffs based upon a weakness in the manuscript itself, a book concept that’s just not likely to sell well in the current market, and a knee-jerk reaction to something as basic as length. It’s far, far too easy to become bitter or to assume, wrongly, that one’s writing can be the only possible reason for rejection.

Don’t do that to yourself, I implore you. It’s not good for you, and it’s not good for your writing.

The second piece I’d like to call to your attention is a fascinating discussion of ethnic diversity (or lack thereof) in the children’s book market by children’s author, poet, and playwright Zetta Elliott. An excerpt would not really do justice to her passionate and persuasive argument against the homogenization of literature — children’s, YA, and adult — but if you’re even vaguely interested in how publishers define who their target markets are and aren’t, and how that can limit where they look for new authorial voices, I would strongly recommend checking out her post.

Back to the business at hand: some of your hands have been waving in the air since the third paragraph of this post. “What on earth do you mean, Anne?” shout impatient hand-raisers everywhere. “I thought synopsis-writing was just yet another annoying hoop through which I was going to need to jump in order to land an agent, a skill to be instrumentally acquired, then swiftly forgotten because I’d never have to use it again. Why would I ever need to write one other than to tuck into a query or submission packet?”

You’re sitting down, I hope? It may come as a surprise to some of you, but synopsis-writing is a task that dogs a professional writer at pretty much every step of her career. Just a few examples how:

* An aspiring writer almost always has to produce one at either the querying or submission stages of finding an agent.

* A nonfiction writer penning a proposal needs to synopsize the book she’s trying to sell, regardless of whether s/he is already represented by an agent.

* Agented writers are often asked to produce a synopsis of a new book projects before they invest much time in writing them, so their agents can assess the concepts’ marketability and start to think about editors who might be interested.

Because the more successful you are as a writer of books, the more often you are likely be asked to produce one of the darned things, synopsis-writing is a fabulous skill to add to your writer’s tool kit as early in your career as possible. Amazingly frequently, though, writers both aspiring and agented avoid even thinking about the methodology of constructing one of the darned things until the last possible nanosecond before they need one, as if writing an effective synopsis were purely a matter of luck or inspiration.

It isn’t. It’s a learned skill. We’re going to be spending this segment of the query packet contents series learning it.

What makes me so sure that pretty much every writer out there could use a crash course in the craft of synopsis writing, or at the very least a refresher? A couple of reasons. First, let me ask you something: if you had only an hour to produce a synopsis for your current book project, could you do it?

Okay, what if I asked you for a 1-page synopsis and gave you only 15 minutes?

I’m not asking to be cruel, I assure you: as a working professional writer, I’ve actually had to work under deadlines that short. And even when I had longer to crank something out, why would I want to squander my scarce writing time producing a document that will never be seen by my readers, since it’s only for internal agency or publishing house use? I’d rather just do a quick, competent job and get on with the rest of my work.

I’m guessing that chorus of small whimpering sounds means that some of you share the same aspiration.

The second reason I suspect even those of you who have written them before could stand a refresher is that you can’t throw a piece of bread at any good-sized writers’ conference in the English-speaking world without hitting at least one writer complaining vociferously about how awful it is to have to summarize a 500-page book in just a couple of pages. I don’t think I’ve ever met a writer at any stage of the game who actually LIKES to write them, but those of us farther along tend to regard them as a necessary evil, a professional obligation to be met quickly and with a minimum of fuss, to get it out of the way.

Judging by conference talk (and, if I’m honest, by the reaction of some of my students when I teach synopsis-writing classes), aspiring writers are more likely to respond with frustration, often to the point of feeling downright insulted by the necessity of synopses for their books at all.

Most often, the complaints center on the synopsis’ torturous brevity. Why, your garden-variety querier shakes his fist at the heavens and cries, need it be so cruelly short? What on earth could be the practical difference between reading a 5-page synopsis and a 6-page one, if not to make a higher hurdle for those trying to break into a notoriously hard-to-break-into business? And how much more could even the sharpest-eyed Millicent learn from a 1-page synopsis that she could glean from a descriptive paragraph in a query letter?

I can answer that last one: about three times as much, usually.

As we’ve already seen with so many aspects of the querying and submission process, confusion about what is required and why often adds considerably to synopsis-writers’ stress. While the tiny teasers required for pitches and query letters are short for practical, easily-understood reasons — time and the necessity for the letter’s being a single page, which also boils down to a time issue, since the single-page restriction exists to speed up Millicent the agency screener’s progress — it’s less clear why, say, an agent would ask to see a synopsis of a manuscript he is ostensibly planning to read.

I sympathize with the confusion, but I must say, I always cringe a little when I hear writers express such resentments. I want to take them aside and say, “Honey, you really need to be careful that attitude doesn’t show up on the page — because, honestly, that happens more than you’d think, and it’s never, ever, EVER helpful to the writer.”

Not to say that these feelings are not completely legitimate in and of themselves, or even a healthy, natural response to a task perceived to be enormous. Let’s face it, the first time most of us sit down to do it, it feels as though we’ve been asked to rewrite our entire books from scratch, but in miniature. From a writerly point of view, if a story takes an entire book-length manuscript to tell well, boiling it down to 5 or 3 or even — sacre bleu! — 1 page seems completely unreasonable, if not actually impossible.

Which it would be, if that were what a synopsis was universally expected to achieve. Fortunately for writers everywhere, it isn’t. Not by a long shot.

Aren’t you glad you were already sitting down?

As I’m going to illustrate over the next week or two, an aspiring writer’s impression of what a synopsis is supposed to be is often quite different from what the pros have become resigned to producing, just as producing a master’s thesis seems like a much, much larger task to those who haven’t written one than those of us who have.

And don’t even get me started on dissertations.

Once a writer comes to understand the actual purpose and uses of the synopsis — some of which are far from self-evident — s/he usually finds it considerably easier to write. So, explanation maven that I am, I’m going to devote this series to clarifying just what it is you are and aren’t being asked to do in a synopsis, why, and how to avoid the most common pitfalls.

Relax; you can do this. Since I haven’t talked about synopses in depth for a good, long while, let’s start with the absolute basics:

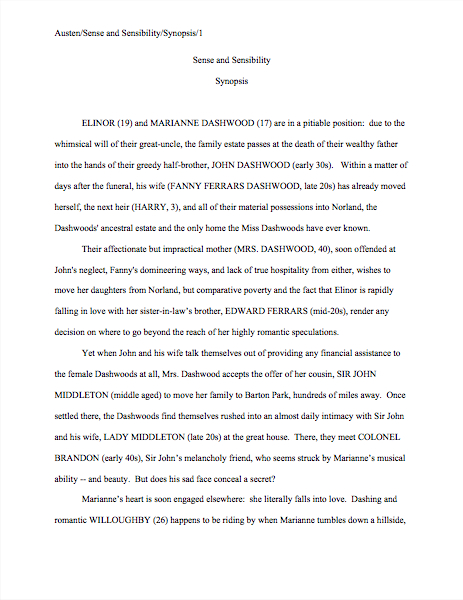

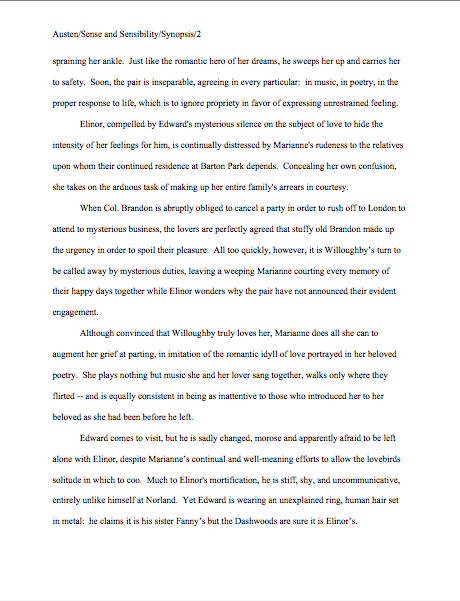

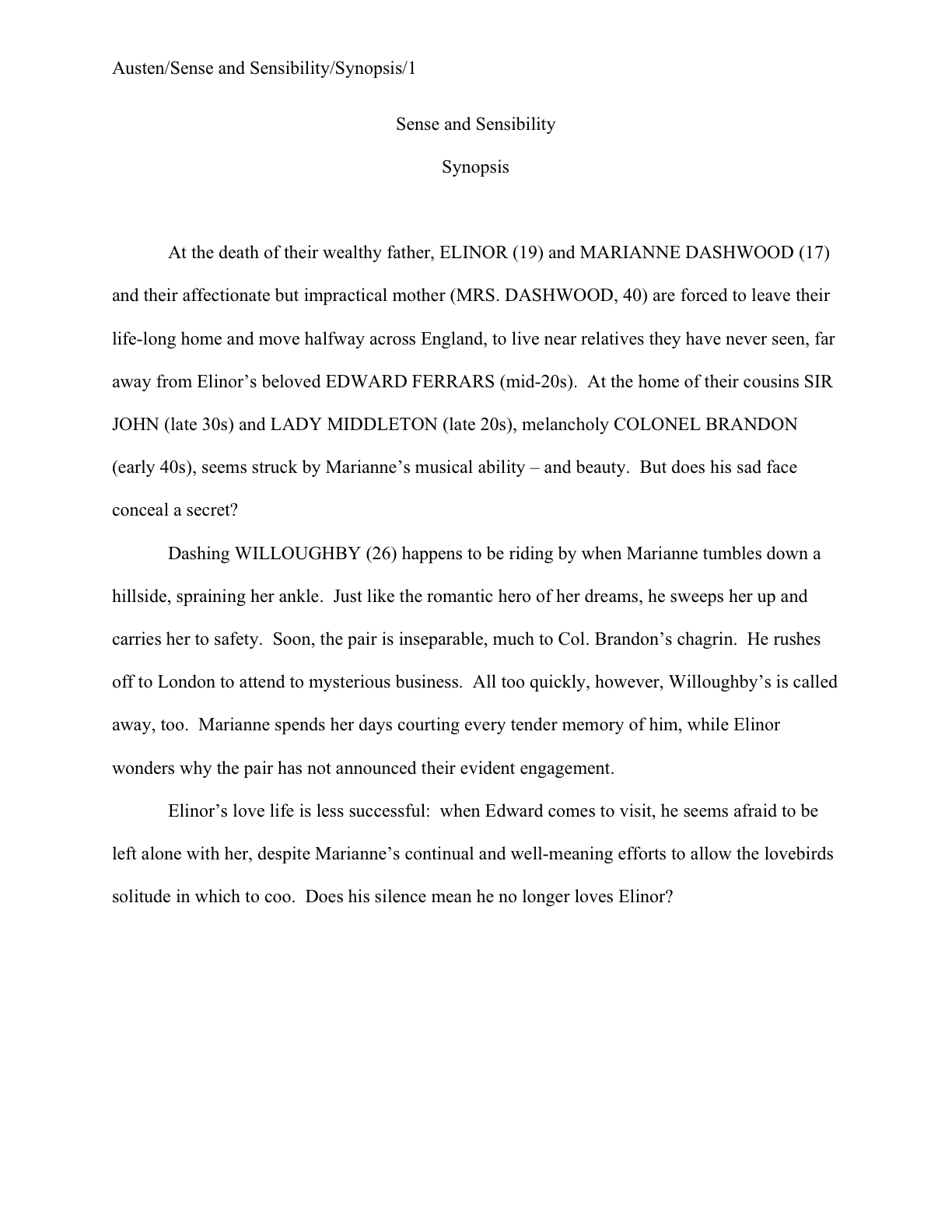

A synopsis is a brief overview IN THE PRESENT TENSE of the entire plot of a novel or the whole argument of a book. Unlike an outline, which presents a story arc in a series of bullet points (essentially), a synopsis is fully fleshed-out prose. Ideally, it should be written in a similar voice and tone to the book it summarizes, but even for a first-person novel, it should be written in the third person.

The lone exception on the voice front: a memoir’s synopsis can be written in both the past tense and should be written in the first person. Go figure. (Don’t worry — I’ll be showing you concrete examples of both in the days to come.)

Typically, professional synopses are 5 pages in standard manuscript format (and thus double-spaced, with 1-inch margins, in Times, Times New Roman, or Courier typefaces; see my parenthetical comment in the examples to come). Querying or submission synopses may be the standard 5 pages or shorter, depending upon the requirements of the requesting agent, editor, or contest — so do make sure to double-check any written guidelines an agency’s website, small press’ submission standards, or contest’s rules might provide.

Yes, Virginia, in the series to come, I will be discussing how to write both long and short versions.

That’s new for me: for the first few years I blogged, I merely talked about the long form, since it was the industry standard; much shorter, and you’re really talking about a book concept (if you’re unfamiliar with the term, please see the BOOK CONCEPT category at right) or a longish pitch, rather than a plot overview. However, over the last couple of years (not entirely uncoincidentally, as more and more agents began accepting e-queries), agencies began to request shorter synopses from queriers, often as little as a single page. There’s nothing like an industry standard for a shorter length, though. Sometimes, an agent will ask for 3, or a contest for 2. It varies.

Let me repeat that a third time, just in case anyone out there missed the vital point: not every agent wants the same length synopsis; there isn’t an absolute industry standard length for a querying, submission, or contest synopsis. So if any of you had been hoping to write a single version to use in every conceivable context, I’m afraid you’re out of luck.

That resentment I mentioned earlier is starting to rise like steam, isn’t it? Yes, in response to that great unspoken shout that just rose from my readership, it would indeed be INFINITELY easier on aspiring writers everywhere if we could simply produce a single submission packet that would fly at any agency in the land.

Feel free to find that maddening — it’s far, far healthier not to deny the emotion. While you’re grumbling, however, let’s take a look at why an agency or contest might want a shorter synopsis.

Like so much else in the industry, time is the decisive factor: synopses are shorthand reference guides that enable overworked agency staffs (yes, Millicent really is overworked — and often not paid very much to boot) to sort through submissions quickly. And obviously, a 1-page synopsis takes less time to read than a 5-page one.

“Well, duh, Anne,” our Virginia huffs, clearly irate at being used as every essayist’s straw woman for decades. “I also understand the time-saving imperative; you’ve certainly hammered on it often enough. What I don’t understand is, if the goal is to save time in screening submissions, why would anyone ever ask for a synopsis that was longer than a page? And if Millicent is so darned harried, why wouldn’t she just go off the descriptive paragraph in the query letter?”

Fabulous questions, Virginia. You’ve come a long way since that question about the existence of Santa Claus.

Remember, though, Ms. V, it’s not as though the average agency or small publishing house reads the query letter and submission side-by-side: they’re often read by different people, under different circumstances. Synopses are often read by people (the marketing department in a publishing house, for instance) who have direct access to neither the initial query nor the manuscript. Frequently, if an agent has asked to see the first 50 pages of a manuscript and likes it, she’ll scan the synopsis to see what happens in the rest of the book. Ditto with contest judges, who have only the synopsis and a few pages of a book in front of them.

And, of course, some agents will use a synopsis promotionally, to cajole an editor into reading a manuscript — but again, 5-page synopses are traditional for this purpose. As nearly as I can tell, the shorter synopses that have recently become so popular typically aren’t used for marketing outside the agency at all.

Why not? Well, realistically, a 1-page synopsis is just a written pitch, not a genuine plot summary, and thus not all that useful for an agent to have on hand if an editor starts asking pesky follow-up questions like, “Okay, so what happens next?”

Do I hear some confused murmuring out there? Let’s let Virginia be your spokesperson: “Wait — this makes it sound as though my novel synopsis is never going to see the light of day outside the agency. If I have to spend all of this time and effort perfecting a synopsis, why don’t all agents just forward it to editors who might be interested, rather than the entire manuscript of my novel?”

Ah, that would be logical, wouldn’t it? But as with so many other flawed human institutions, logic does not necessarily dictate why things are done the way they are within the industry; much of the time, tradition does.

Thus, the argument often heard against trying to sell a first novel on synopsis alone: fiction is just not sold that way, my dear. Publishing houses buy on the manuscript itself, not the summary. Nonfiction, by contrast, is seldom sold on a finished manuscript.

So for a novel, the synopsis is primarily a marketing tool for landing an agent, rather than something that sticks with the book throughout the marketing process. (This is not true of nonfiction, where the synopsis is part of the book proposal. For some helpful how-to on constructing one, check out the HOW TO WRITE A BOOK PROPOSAL on the archive list at right.)

I’m not quite sure why agents aren’t more upfront at conferences about the synopsis being primarily an in-house document when they request it. Ditto with pretty much any other non-manuscript materials they request from a novelist — indications of target market, author bio, etc. (For nonfiction, of course, all of these would be included within the aforementioned book proposal.)

Requiring this kind of information used to be purely the province of the non-fiction agent. Increasingly over the last decade or so, however, fiction writers are being asked to provide this kind of information to save agents — you guessed it — time. Since the tendency in recent years has been to transfer as much of the agents’ work to potential clients as possible, it wouldn’t surprise me in the slightest if agents started asking for the full NF packet from novelists within the next few years.

Crunching a dry cracker should help quell the nausea that prospect induced, Virginia. Let’s not worry about that dread day until it happens, shall we? For now, let’s stick to the current requirements.

Why is the 5-page synopsis more popular than, say, 3 pages? Well, 5 pages in standard format is roughly 1250 words, enough space to give some fairly intense detail. By contrast, a jacket blurb is usually between 100 and 250 words, only enough to give a general impression or set up a premise.

I point this out, because far too many writers new to the biz submit jacket blurbs to agents, editors, and contests, rather than synopses: marketing puff pieces, rather than plot descriptions or argument outlines. This is a mistake: publishing houses have marketing departments for producing advertising copy.

And in a query packet synopsis, praise for a manuscript or book proposal, rather than an actual description of its plot or premise, is not going to help Millicent decide whether her boss is likely to be interested in the book in question. In a synopsis from a heretofore-unpublished writer, what industry professionals want to see is not self-praise, or a claim that every left-handed teenage boy in North America will be drawn to this book (even it it’s true), but a summary of what the book is ABOUT.

In other words, like the query, the synopsis is a poor place to boast. Since the jacket blurb-type synopsis is so common, many agencies use it as — wait for it, Virginia — an easy excuse to reject a submission unread.

Yes, that’s a trifle unfair to those new to the biz, but the industry logic runs thus: a writer who doesn’t know the difference between a blurb and a synopsis is probably also unfamiliar with other industry norms, such as standard format and turn-around times. Thus (they reason), it’s more efficient to throw that fish back, to wait until it grows, before they invest serious amounts of time in frying it.

With such good bait, they really don’t stay up nights worrying about the fish that got away.

“In heaven’s name,” Virginia cries, “WHY? They must let a huge number of really talented writers who don’t happen to know the ropes slip through their nets!”

To borrow your metaphor, Virginia, there are a whole lot of fish in the submission sea — and exponentially more in the querying ocean. as I MAY have pointed out once or twice before in this forum, agencies (and contests) typically receive so many well-written submissions that their screeners are actively looking for reasons to reject them, not to accept them. An unprofessional synopsis is an easy excuse to thin the ranks of the contenders.

Before anyone begins pouting: as always, I’m pointing out the intensity of the competition not to depress or intimidate you, but to help you understand just how often good writers get rejected for, well, reasons other than the one we all tend to assume. That fact alone strikes me as excellent incentive to learn what an agency, contest, or small publisher wants to see in a synopsis.

And let him have it just that way, to quote the late, great Fats Waller.

The hard fact is, they receive so many queries in any given week that they can afford to be as selective as they like about synopses — and ask for any length they want. Which explains the variation in requested length: every agent, just like every editor and contest judge, is an individual, not an identical cog in a mammoth machine. An aspiring writer CAN choose ignore their personal preferences and give them all the same thing — submitting a 5-page synopsis to one but do you really want to begin the relationship by demonstrating an inability to follow directions?

I know: it’s awful to think of one’s own work — or indeed, that of any dedicated writer — being treated that way. If I ran the universe, synopses would not be treated this way. Instead, each agency would present soon-to-query writers with a clear, concise how-to for its preferred synopsis style — and if a writer submitted a back jacket blurb, Millicent the agency screener would chuckle indulgently, hand-write a nice little note advising the writer to revise and resubmit, then tuck it into an envelope along with that clear, concise list.

Or, better yet, every agency in the biz would send a representative to a vast agenting conference, a sort of UN of author representation, where delegates would hammer out a set of universal standards for judging synopses, to take the guesswork out of it once and for all. Once codified, bands of laughing nymphs would distribute these helpful standards to every writer currently producing English prose, and bands of freelance editors would set up stalls in the foyers of libraries across the world, to assist aspiring writers in conforming to the new standards.

Unfortunately, as you may perhaps have noticed in recent months, I do not run the universe, so we writers have to deal with the prevailing lack of clear norms. However much speakers at conferences, writing gurus, and agents themselves speak of the publishing industry as monolithic, it isn’t: individual agents, and thus individual agencies, like different things.

The result is — and I do hate to be the one to break this to you, Virginia — no single synopsis you write is going to please everybody in the industry.

Sounds a bit familiar? It should — the same principle applies to query letters.

As convenient as it would be for aspiring writers everywhere if you could just write the darned things once and make copies as needed, it’s seldom in your interest to do so. Literally the only pressure for standardization comes from writers, who pretty uniformly wish that there were a single formula for the darned thing, so they could write it once and never think about it again.

You could make the argument that there should be an industry standard until you’re blue in the face, but the fact remains that, in the long run, you will be far, far better off if you give each what s/he asks to see. Just that way.

Well, so much for synopses. Tomorrow, we’ll move on to author bios.

Just kidding; the synopsis is a tall order, and I’m going to walk you through both its construction and past its most common pitfalls. In a couple of weeks, you’ll be advising other writers how to do it — and you’ll have yet another formidable tool in your marketing kit.

Keep asking those probing questions, Virginia: this process is far from intuitive. And, as always, keep up the good work!