Fair warning, campers: today’s is going to be a long, long post, even by my standards. Yes, I could have chopped it in half, but for the sake of readers in the months to come who will be tracking down the rules-only part of this series on standard format for manuscripts in the archives, I wanted to cram the list of rules into as few posts as possible.

While the applying these rules to a manuscript already in progress may seem like a pain, remember, practice makes habitual. After a while, the impulse to conform to the rules of standard format becomes second nature. Trust me, it’s a learned instinct that can save a writer oodles of time and misery come deadline time.

How, you ask? Well, to a writer for whom proper formatting has become automatic, there is no last-minute scramble to change the text. It came into the world correct — which, in turn, saves a writer revision time.

And sometimes, those conserved minutes and hours can save the writer’s proverbial backside as well. Scoff not: even a psychic with a very, very poor track record for predictions could tell you that there will be times in your career when you don’t have the time to proofread as closely as you would like. At some point, that half an hour it would take to reformat will make the difference between making and missing your deadline.

Perversely, this is a kind of stress that will probably make you happy — perhaps not in the moment you are experiencing it, but in general. The more successful you are as a writer — ANY kind of writer — the more often you will be in a hurry, predictably. No one has more last-minute deadlines than a writer with a book contract…just ask any author whose agent is breathing down her neck after a deadline has passed. Or about which neither the editor nor agent remembered to tell her in the first place.

Oh, how I wish I were kidding about that. And don’t even get me started on the phenomenon of one’s agent calling the day after Thanksgiving to announce, “I told the editor that you could have the last third of the book completely reworked by Christmas — that’s not going to be a problem, is it?”

Think you’re going to want to be worrying about your formatting at that juncture? (And no, I wasn’t making up that last example, either; I had a lousy holiday season that year, as long-term readers of this blog may recall.) Believe me, you’re going to be kissing yourself in retrospect for learning how to handle the rote matters right the first time, so you can concentrate on the hard stuff.

That’s the good news about how easily standard format sinks into one’s very bones. The down side, is that once people — like, say, the average agent, editor, or Millicent — have spent enough time staring at professionally-formatted manuscripts, anything else starts to look, well, unprofessional.

The implications of this mindset are vast. First, it means that IF AN AGENT OR EDITOR REQUESTED YOU TO SEND PAGES, S/HE IS EXPECTING THEM TO BE IN STANDARD FORMAT, unless s/he SPECIFICALLY tells you otherwise.

Translation: it’s so much assumed that s/he probably won’t even mention it, because most agents and editors believe that these rules are already part of every serious book-writer’s MO.

So much so, in fact, that agents who’ve read my blog sometimes ask me why I go over these rules so often. Doesn’t everyone already know them? Isn’t this information already widely available? Aren’t there, you know, books on how to put a manuscript together?

I’ll leave those of you reading this post to answer those for yourselves. Suffice it to say that our old pal Millicent the agency screener believes the answers to be: because I like it, yes, yes, and yes.

Second, this mindset means that seemingly little choices like font and whether to use a doubled dash or an emdash — of which more below — can make a HUGE difference to how Millicent perceives a manuscript. (Yes, I know: I point this out with some frequency. However, as it still seems to come as a great surprise to the vast majority aspiring writers; I can only assume that my voice hasn’t been carrying very far when I’ve said it the last 700 times.)

I hate to be the one to break it to you, but professional-level critique is HARSH; it’s like having your unmade-up face examined under a very, very bright light by someone who isn’t afraid to hurt your feelings by pointing out flaws. In the industry, this level of scrutiny is not considered even remotely mean. Actually, if your work generates tell-it-like-it-is feedback from a pro, you should be a bit flattered — it’s how they habitually treat professional authors.

Yet the aforementioned vast majority of submitting writers seem to assume, at least implicitly, that agents and their staffs will be hugely sympathetic readers of their submissions, willing to overlook technical problems because of the quality of the writing or the strength of the story.

I’m not going to lie to you — every once in a very, very long while, the odd exception that justifies this belief does in fact occur. If the writing is absolutely beautiful, or the story is drool-worthy, but the formatting is all akimbo and the spelling is lousy, there’s an outside chance that someone at an agency might be in a saintly enough mood to overlook the problems and take a chance on the writer.

You could also have a Horatio Alger moment where you find a billionaire’s wallet, return it to him still stuffed with thousand-dollar bills, and he adopts you as his new-found son or daughter.

Anything is possible, of course. But it’s probably prudent to assume, when your writing’s at stake, that yours is not going to be the one in 10,000,000 exception.

Virtually all of the time, an agent, editor, contest judge, or screener’s first reaction to an improperly-formatted manuscript is the same as to one that is dull but technically perfect: speedy rejection.

Yes, from a writerly point of view, this is indeed trying. Yet as I believe I may have mentioned once or twice before, I do not run the universe, and thus do not make the rules.

Sorry. No matter how much I would like to absolve you from some of them, it is outside my power. Take it up with the fairy godmother who neglected to endow me with that gift at birth, okay?

Until you have successfully made your case with her, I’m going to stick to using the skills that she DID grant me, a childhood filled with professional writers who made me learn to do it the right way the first time. Let’s recap some of the habits they inculcated, shall we?

(1) All manuscripts should be printed or typed in black ink and double-spaced, with one-inch margins around all edges of the page, on 20-lb or better white paper.

(2) All manuscripts should be printed on ONE side of the page and unbound in any way.

(3) The text should be left-justified, NOT block-justified. By definition, manuscripts should NOT resemble published books in this respect.

(4) The preferred typefaces are 12-point Times, Times New Roman, Courier, or Courier New — unless you’re writing screenplays, in which case you may only use Courier. For book manuscripts, pick one (and ONLY one) and use it consistently throughout your entire submission packet.

(5) The ENTIRE manuscript should be in the same font and size. Industry standard is 12-point.

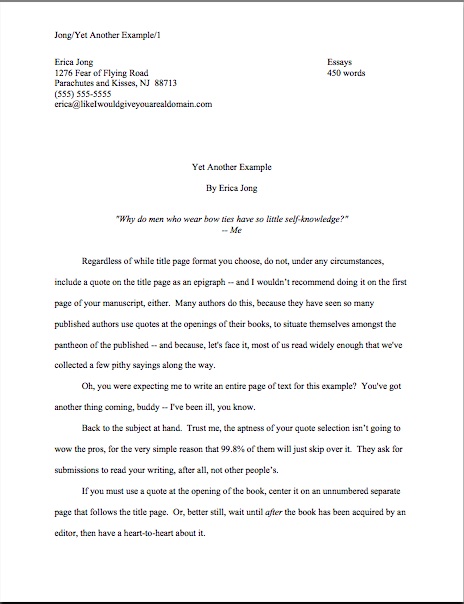

(6) Do NOT use boldface anywhere in the manuscript BUT on the title page — and not even there, necessarily.

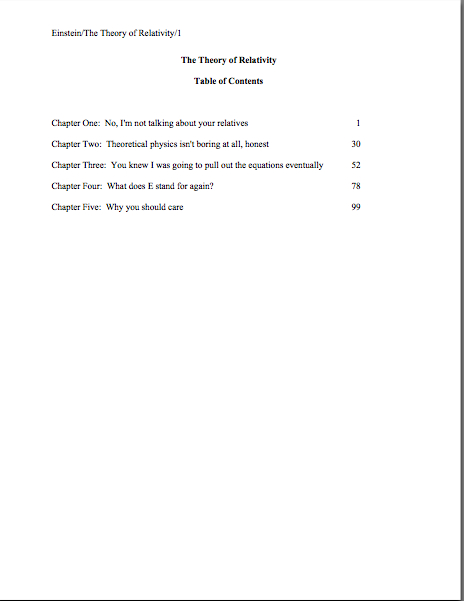

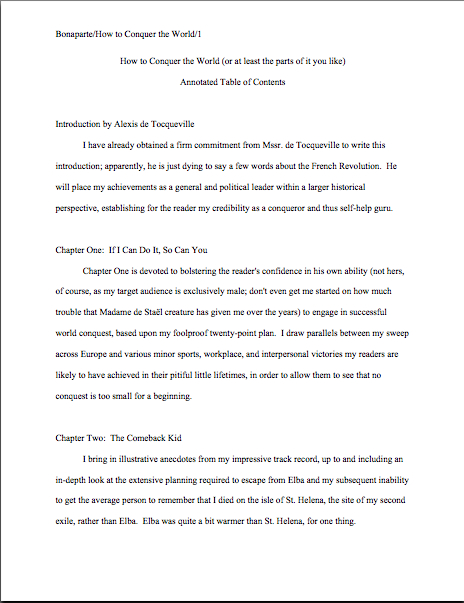

(7) EVERY page in the manuscript should be numbered EXCEPT the title page.

(8) Each page of the manuscript (other than the title page) should have a standard slug line in the header. The page number should appear in the slug line, not anywhere else on the page.

(9) The first page of each chapter should begin a third of the way down the page, with the chapter title appearing on the FIRST line of the page, NOT on the line immediately above where the text begins.

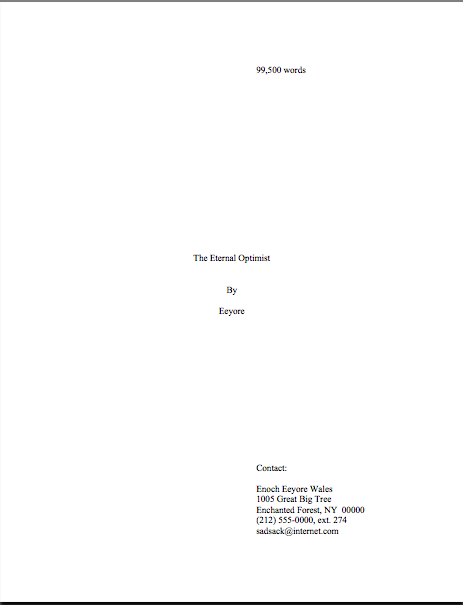

(10) Contact information for the author belongs on the title page, NOT on page 1.

(11) Every submission should include a title page, even partial manuscripts.

Everyone clear on all that? Good. Let’s move on.

(12) The beginning of EVERY paragraph of text should be indented five spaces. No exceptions, EVER.

To put it another way: NOTHING you send to anyone in the industry should EVER be in block-style business format. And for a pretty good reason: despite the fact that everyone from CEOs to the proverbial little old lady from Pasadena has been known to use block format from time to time(and blogs are set up to use nothing else), technically, non-indented paragraphs are not proper for English prose.

Period. Don’t bother quibbling about it — and don’t skip lines between paragraphs, either. (The logic for that last bit follows in a moment, never fear.)

That loud clicking sound that some of you may have found distracting was the sound of light bulbs going on over the heads of all of those readers who have been submitting their manuscripts (and probably their queries as well) in block paragraphs. Yes, what all of you newly well-lit souls are thinking right now is quite true: those queries and submissions may well have been rejected at first glance by a Millicent in a bad mood. (And when, really, is she not?)

Yes, even if you submitted those manuscripts via e-mail. (See why I’m always harping on how submitting in hard copy, or at the very worst as a Word attachment, is inherently better for a submitter?)

Why the knee-jerk response? Well, although literacy has become decreasingly valued in the world at large, the people who have devoted themselves to bringing good writing to publications still tend to take it awfully darned seriously. To publishing types, any document with no indentations, skipping a line between paragraphs, and the whole shebang left-justified carries the stigma of (ugh) business correspondence — and that’s definitely not good.

Why, you ask? Well, do you really want the person you’re trying to impress with your literary genius to wonder about your literacy?

I thought not. And which do you think is going to strike format-minded industry professionals as more literate, a query letter in business format or one in correspondence format (indented paragraphs, date and signature halfway across the page, no skipped line between paragraphs)?

Uh-huh. And don’t you wish that someone had told you THAT before you sent out your first query letter?

Trust me on this one: indent your paragraphs in any document that’s ever going to pass under the nose of anyone even remotely affiliated with the publishing industry.

Including the first paragraph of every chapter, incidentally. Yes, published books — particularly mysteries, I notice — often begin chapters and sections without indentation. But again, that lack of indentation was the editor’s choice, not the author’s, and copying it in a submission, no matter to whom it is intended as an homage, might get your work knocked out of consideration.

(13) Don’t skip an extra line between paragraphs, except to indicate a section break.

I’m serious about that being the ONLY exception: skip an extra line to indicate a section break in the text, and for no other reason.

Really, this guideline is just common sense — so it’s a continual surprise to professional readers how often we see manuscripts that are single-spaced with a line skipped between paragraphs (much like blog format, seen here in all of its glory).

Why surprising? Well, since the entire manuscript should be double-spaced with indented paragraphs, there is no need to skip a line to indicate a paragraph break. (Which is, in case you were not aware of it, what a skipped line between paragraph means in a single-spaced or non-indented document.) In a double-spaced document, a skipped line means a section break, period.

Also — and this is far from insignificant, from a professional reader’s point of view — it’s COMPLETELY impossible to edit a single-spaced document, either in hard copy or on screen. The eye skips between lines too easily, and in hard copy, there’s nowhere to scrawl comments like Mr. Dickens, was it the best of times or was it the worst of times? It could hardly have been both!

So why do aspiring writers so often blithely send off manuscripts with skipped lines, single-spaced or otherwise? My guess would be for one of two reasons: either they think business format is proper English formatting (which it isn’t) or they’re used to seeing skipped lines in print. Magazine articles, mostly.

But — feel free to shout it along with me now; you know the words — A MANUSCRIPT SHOULD NOT RESEMBLE A PUBLISHED PIECE OF WRITING.

The * * * section break is obsolete, as is the #; no one will fault you for using either — although most Millicents will roll their eyes upon seeing one of these old-fashioned formats, the latter is in fact proper for short story format. However, every agent I know makes old-fashioned writers take them out of book manuscripts prior to submission — but still, these throwbacks to the age of typewriters are no longer necessary in a submission to an agency or publishing house.

Why were they ever used at all? To alert the typesetter that the missing line of text was intentional.

One caveat to contest-entrants: do check contest rules carefully, because some competitions still require * or #. You’d be amazed at how seldom long-running contests update their rules.

(14) NOTHING in a manuscript should be underlined. Titles of songs and publications, as well as words in foreign languages and those you wish to emphasize, should be italicized.

Fair warning: if you consult an old style manual (or a website that is relying upon an old style manual), you may be urged to underline the words and phrases mentioned above. And just so you know, anyone who follows AP style will tell you to underline these. As will anyone who learned how to format a manuscript before the home computer became common, for the exceedingly simple reason that the average typewriter doesn’t feature italic keys as well as regular type; underlining used to be the only option.

DO NOT LISTEN TO THESE TEMPTERS: AP style is for journalism, not book publishing. They are different fields, and have different standards. And although I remain fond of typewriters — growing up in a house filled with writers, the sound used to lull me to sleep as a child — the fact is, the publishing industry now assumes that all manuscripts are produced on computers. In Word, even.

So DO NOT BE TEMPTED. In a submission for the book industry, NOTHING should be underlined. Ever.

Professional readers are AMAZED at how often otherwise perfectly-formatted manuscripts get this backwards — seriously, many’s the time that a bunch of us has sat around and talked about it at the bar that’s never more than 100 yards from any writers’ conference in North America. According to this informal and often not entirely sober polling data, an aspiring writer would have to be consulting a very, very outdated list of formatting restrictions to believe that underlining is ever acceptable.

Or, to put it another way: since your future agent is going to make you change all of that underlining to italics anyway, you might as well get out of the habit of underlining now. Like, say, before submitting your manuscript — because if Millicent happens to be having a bad day (again, what’s the probability?) when she happens upon underlining in a submission, she is very, very likely to roll her eyes and think, “Oh, God, not another one.”

Italics are one of the few concessions manuscript format has made to the computer age — again, for practical reasons: underlining uses more ink than italics in the book production process. Thus, italics are cheaper. So when should you use them and why?

(a) The logic behind italicizing foreign words is very straightforward: you don’t want the agent of your dreams to think you’ve made a typo, do you?

(b) The logic behind using italics for emphasis, as we’ve all seen a million times in print, is even more straightforward: writers used to use underlining for this. So did hand-writers.

(c) Some authors like to use italics to indicate thought, but there is no hard-and-fast rule on this. Before you make the choice, do be aware that many agents and editors actively dislike this practice. Their logic, as I understand it: a good writer should be able to make it clear that a character is thinking something, or indicate inflection, without resorting to funny type.

I have to confess, as a reader, I’m with them on that last one, but that’s just my personal preference.

However, there are many other agents and editors who think it is perfectly fine — but you are unlikely to learn which is which until after you have sent in your manuscript, alas. You submit your work, you take your chances.

There is no fail-safe for this choice. Sorry.

(15) All numbers (except for dates) under 100 should be written out in full: twenty-five, not 25. But numbers over 100 should be written as numbers: 1,243, not one thousand, two hundred and forty-three.

I’m surprised how often otherwise industry-savvy writers are unaware of this one, but the instinct to correct it in a submission is universal in professional readers. Translation: NOT doing it will not help you win friends and influence people at agencies and publishing houses.

Like pointing out foreign-language words with special formatting, this formatting rule was originally for the benefit of the manual typesetters. When numbers are entered as numbers, a single slip of a finger can result in an error, whereas when numbers are written out, the error has to be in the inputer’s mind.

Again, be warned, those of you who have been taught by teachers who adhere to the AP style: they will tell you to write out only numbers under 10.

Yes, this is true for newspaper articles, where space is at a premium, but in a book manuscript, it is WRONG, WRONG, WRONG.

Did I mention it was wrong? And that my aged eyes have actually seen contest entries knocked out of finalist consideration over this particular issue? More than once? And within the year?

(16) Dashes should be doubled — rather than using an emdash — with a space at either end. Hyphens are single and are not given extra spaces at either end, as in self-congratulatory.

Yes, yes, I know: you’ve probably heard that this rule is obsolete, too, gone the way of underlining. The usual argument for its demise: books no longer preserve these spaces, for reasons of printing economy, so many writing teachers tell their students just to go ahead and eliminate them. An AP-trained teacher will tell you to use the longer emdash, as will the Chicago Manual of Style.

In this, however, they are wrong, at least as far as manuscripts are concerned. Standard format is invariable upon this point: a doubled dash with a space on either end is correct; anything else is not. And yes, it is indeed a common enough pet peeve that the pros will complain to one another about how often submitters do it.

They also whine about how often they see manuscripts where this rule is applied inconsistently: two-thirds of the dashes doubled, perhaps, sometimes with a space at either end and sometimes not, with the odd emdash and single dash dotting the text as well. It may seem like a minor, easily-fixable phenomenon from the writer’s side of the submission envelope, but believe me, inconsistency drives people trained to spot minor errors nuts.

Your word-processing program probably changes a double dash to an emdash automatically, but CHANGE IT BACK. Any agent would make you do this before agreeing to submit your manuscript to an editor, so you might as well get into this salutary habit as soon as possible.

(17) Adhere to the standard rules of punctuation and grammar, not what it being done on the moment in newspapers, magazines, books, or on the Internet — including the rule calling for TWO spaces after every period and colon.

In other words, do as Strunk & White say, not what others do. Assume that Millicent graduated with honors from the best undergraduate English department in the country, taught by the grumpiest, meanest, least tolerant stickler for grammar that ever snarled at a student unfortunate enough to have made a typo, and you’ll be fine.

Imagining half the adults around me in my formative years who on the slightest hint of grammatical impropriety even in spoken English will work, too.

The primary deviation from proper grammar I’ve been seeing in recent years is leaving only one space, rather than the standard two, after a period. Yes, printed books often do this, to save paper (the fewer the spaces on a page, the more words can be crammed onto it, right?). A number of writing-advice websites, I notice, and even some writing teachers have been telling people that this is the wave of the future — and that adhering to the two-space norm makes a manuscript look obsolete.

At the risk of sounding like the harsh grammar-mongers of my youth, poppycock.

There is a very, very practical reason to preserve that extra space after each sentence in a manuscript: ease of reading and thus editing. As anyone who has ever edited a long piece of writing can tell you, the white space on the page is where the comments — grammatical changes, pointing out flow problems, asking, “Does the brother really need to die here?” — go.

Less white space, less room to comment. It really is that simple.

Translation: until everyone in the industry makes the transition editing in soft copy — which is, as I have pointed out many times in this forum, both harder and less efficient than scanning a printed page — the two-space rule is highly unlikely to change.

However, as some of you are probably already gearing up to tell me in the comments, one does hear differing opinions on this subject; it’s not all that uncommon, for instance, for an agent relatively new to the game to announce at conferences that NOBODY still expects that single space. If you’re planning to submit to her, by all means, listen to her — but I would advise against assuming that she is speaking for everybody in the industry.

Why? Well, the agents and editors who still edit in hard copy feel pretty strongly about the two-space rule — which is, incidentally, still the norm for typing in the English language; I’ve literally never heard an editor at a conference insist that the norm is a single space, for instance, although that will probably change over time as the industry becomes more computer-savvy. So whenever I hear a young agent telling a roomful of eager aspiring writers that absolutely nobody in publishing wants to see the second space after the period anymore, I always think, “I wonder if he’ll still be giving that advice after the first time submits to an old-school senior editor who lectures him for fifteen minutes on the rules of the English language.”

Because the old-schoolers are, if anything, more vehement than the advocates for change, I would not allow any of my editing clients submit with a single space. Nor have any of them (or I) ever been asked to change their two spaces after periods and colons to a single space. I just mention.

All of which is to say: make your own choice and be consistent about it throughout your manuscript; don’t kid yourself that an experienced professional reader isn’t going to notice if you sometimes use one format, sometimes the other. (Later in this series, I will show you the same page of text both ways, so you may see why it’s pretty obvious which is being used.)

There you have it: the rules. Practice them until they are imbedded into your very bones, my friends: literally every page of text you submit to an agent, editor, or literary contest (yes, including the synopsis) for the rest of your professional life should be in standard format.

Oh, and it’s a good idea to make sure everything is spelled correctly, too, and to turn off the widow/orphan control; it makes pages into an uneven number of lines.

If you’re having a hard time absorbing all of these rules in one fell swoop, don’t despair: for the next couple of weeks, we’re going to be observing them in their natural habitat, the manuscript.

Tomorrow, though, I’m going to take a break in this rather breathless series to bring you a treat: another post in our episodic series on various aspects of censorship. Make sure to tune in; this one’s going to be especially fascinating for any of you who ever gave even passing thought to whether your work could possibly fit comfortably within a single book category.

In the meantime, keep pondering your entries for the First Periodic Author! Author! Awards for Expressive Excellence — and, as always, keep up the good work!