Have you noticed a theme running through the last few posts, campers? Yes, we’ve ostensibly been talking about dialogue, but in that fine tradition of narrative where there’s more going on than what’s going on, as Millicent the agency screener might put it, I’ve been sneaking in some other lessons as well. Many of them, as some of you may have noticed, have related to reducing the passivity of one’s protagonist(s).

On the off chance that I’ve been too subtle: a protagonist who merely observes the plot, rather than being a force — or, ideally, the primary force — driving it forward can bring an otherwise exciting story to a grinding halt while s/he ruminates. (Confidential to Elizabeth: you’re welcome.) Similarly, a protagonist who contributes minimally to a scene, remains silent, or does not respond to stimuli that would cause the calmest herd of elephants to stampede for the nearest exit can sap tension.

So it’s not entirely surprising, is it, that a protagonist who is purely reactive on page 1 might cause Millicent to worry about how exciting s/he will be to follow for the rest of the book? Let’s face it, even if the opening scene is chock full of unexpected conflict, seeing it through the eyes and psyche of a protagonist seemingly determined not to get involved, or even one who just doesn’t ask particularly incisive questions, may make it seem, well, less exciting.

Not to mention making the protagonist come across as less intelligent than the author probably intended. Last time, we saw how a character’s repeating what has just been said to him can markedly lowers his apparent I.Q. by a few dozen points. When a protagonist stops the story in its tracks to draw conclusions that would cause a reasonably intelligent eight-year-old to exclaim, “Well, duh!”, it can have a similar effect. Imagine, for instance, having to follow Pauline through a 380-page novel.

Pauline struggled against her bonds, but it was no use. Her tormentor must have been an Eagle Scout with a specialty in knotting, to tie her to the railroad track this firmly. “You don’t mean to…hurt me, do you?”

“Of course not.” Edgar sneered, twirling his mustache. “It’s the oncoming train that’s going to hurt you. Quite a lot, I should think.”

Her eyes widened to the circumference of her Aunt Bettina’s favorite teacups, the ones with the wee lilacs painted upon them. “Are you trying to kill me? Why? What have I ever done to you?”

“Oh, I don’t know.” Depressed, he flopped onto a nearby pile of burlap sacks. “I just have this thing for tying pretty women to railroad tracks. You happened to be here.” He buried his head in his elegant hands. “God, I really need to establish some standards.”

Was he weakening? Over the roar of the engine, it was so hard to be sure. “Edgar? If you don’t do something, I shall be squashed flatter than the proverbial pancake.”

He did not even lift his head. “I doubt it. With my luck, a handsome stranger will suddenly appear to rescue you.”

A shadow crossed her face. “Why, hello there, little lady,” a stranger blessed with undeniable good looks said. “You look like you could use some help.”

She had to shout to be heard over the wheels. “Yes, I could. You see, Edgar’s tied me to the train tracks, and there’s a train coming.”

Miffed at me for ending the scene before we found out it Pauline survived? Come on, admit it — you were tempted to shout, “Well, duh!” in response to some of Pauline’s statements, were you not? Who could blame you, when apparently her only role in the scene is to point out the obvious?

Millicent would have stopped reading, too, but she would have diagnosed the problem here differently. “Why doesn’t this writer trust my intelligence?” she would mutter, reaching for the nearest form-letter rejection. “Why does s/he assume that I’m too stupid to be able to follow this series of events — and a cliché-ridden series of events at that — without continual explanations of what’s going on?”

That’s a question for the ages, Millicent. In this case, the writer may have considered Pauline’s affection for the obvious funny. Or those frequent unnecessary statements may be Hollywood narration: instead of the narrative’s showing what’s happening, the dialogue’s carries the burden, even though the situation must be clear to the two characters to whom Pauline is speaking.

Or — and this is a possibility we have not yet considered in this series — this scene is lifted from a book category where the imperiled protagonist is expected to be purely reactive.

Didn’t see that one coming, did you? All too often, those of us who teach writing to writers speak as though good writing were good writing, independent of genre, but that’s not always the case. Every book category has its own conventions; what would be considered normal in one may seem downright poky in another.

Case in point: our Pauline. Her tendency to lie there and wait for someone to untie her would be a drawback in a mainstream fiction or high-end women’s fiction manuscript, but for a rather wide segment of the WIP (Women in Peril) romance market, a certain amount of passivity is a positive boon. Heck, if this example were WIP, Pauline might not only be tied to a train track — she might be menaced by a lion wielding a Tommy gun.

As opposed to, say, a bulletproof lady too quick to be lashed down with large steaks in her capacious pockets in case of lion attack. The latter would make a great heroine of an Action/Adventure — and the last thing Millicent would expect her to be is passive.

Unless, of course, Pauline is the love interest in a thriller. Starting to see how this works?

Even if she were a passive protagonist in a genre more accepting of passivity (usually in females; in the U.S., genuinely passive male protagonists tend to be limited to YA or literary fiction), it would dangerous to depict the old girl being purely reactive on page 1: the Millicent who reads WIP at the agency of your dreams may also be screening fantasy, science fiction, mystery, or any of the other genres that tend to feature active female protagonists. As a general rule, then, it’s better strategy to show your protagonist being active and smart on page 1.

Which is to say: place your protagonist in an exciting situation, not just next to it.

Also, you might want to make it clear from the first line of page 1 who your protagonist is. Not who in the philosophical sense, or even in the demographic sense, but which character the reader is supposed to be following.

Stop laughing; this is a serious issue for our Millie. Remember, in order to recommend a manuscript to her boss, she has to be able to tell the agent of your dreams what the book is about — and about whom. Being a literary optimist, she begins each new submission with the expectation that she’s going to be telling her boss about it.

Unless the text signals her otherwise, she’s going to assume that the first name mentioned is the protagonist’s. Imagine her dismay, then, when the book turns out a page, or two, or fifty-seven later to be about someone else entirely.

I can still hear you giggling, but seriously, it’s often quite hard to tell. Don’t believe me? Okay, here’s a fairly typical opening page in a close third-person Women’s Fiction narrative. Based on the first few lines, who is the protagonist?

Were you surprised by the sudden switch to Emma? Millicent would have been. Perhaps not enough to stop reading, but enough to wonder why the first half-page sent her assumptions careening in the wrong direction.

That little bait-and-switch would be even more likely to annoy her on this page than others, because Emma seems like the less interesting protagonist option here. Not only is she an observer of the action — Casey’s the one experiencing the tension, in addition to having apparently been married to someone with allegedly rather nasty habits — but she comes across as, well, a bit slow on the uptake.

How so, you ask? Do you know very many super-geniuses who have to count on their fingers to tell time?

Now, as a professional reader, it’s fairly obvious to me that the writer’s intention here was not to make Emma seem unintelligent. My guess would be that the finger-counting episode is merely an excuse to mention how the rings threw the dull light back at the ceiling — not a bad image for a first page. But that wasn’t what jumped out at you first from this page, was it?

Or it wouldn’t have, if you were Millicent. There are three — count ‘em on your fingers: three — of her other pet peeves just clamoring for her attention. Allow me to stick a Sharpie in her hand and let her have at it:

Thanks, Millie; why don’t you go score yourself a latte and try to calm down a little? I can take it from here.

Now that we’re alone again, be honest: in your initial scan of the page, had you noticed all of the issues that so annoyed Millicent? Any of them?

Probably not, if you were reading purely for story and writing style, instead of the myriad little green and red flags that are constantly waving at her from the submission page. Let’s take her concerns one at a time, so we may understand why each bugged her — and consider whether they would have bugged her in submissions in other book categories.

Opening with an unidentified speaker: Millicent remains perpetually mystified by how popular such openings are. Depending upon the categories her boss represents, she might see anywhere from a handful to dozens of submissions with dialogue as their first lines on any given day. A good third of those will probably not identify the speaker right off the bat.

Why would the vast majority of Millicents frown upon that choice, other than the sheer fact that they see it so very often? A very practical reason: before they can possibly make the case to their respective boss agents that this manuscript is about an interesting protagonist faced with an interesting conflict, they will have to (a) identify the protagonist, (b) identify the primary conflict s/he faces, and (c) determine whether (a) and (b) are interesting enough to captivate a reader for three or four hundred pages.

Given that mission, it’s bound to miff them if they can’t tell if the first line of the book is spoken by the protagonist — or, indeed, anyone else. In this case, the reader isn’t let in on the secret of the speaker’s identity for another 6 lines. That’s an eternity, in screeners’ terms — especially when, as here, the first character named turns out not to be the speaker. And even on line 7, the reader is left to assume that Emma was the initial speaker, even though logically, any one of the everyone mentioned in line 7 could have said it.

So let me give voice to the question that Millicent would be asking herself by the middle of the third line: since presumably both of the characters introduced here knew who spoke that first line, what precisely did the narrative gain by not identifying the speaker for the reader’s benefit on line 1?

99.9% of the time, the honest answer will be, “Not much.” So why force Millicent to play a guessing game we already know she dislikes, if it’s not necessary to the scene?

Go ahead and tell her who is speaking, what’s going on, who the players are, and what that unnamed thing that jumps out of the closet and terrifies the protagonist looks like. If you want to create suspense, withholding information from the reader is not Millicent’s favorite means of generating it.

That’s not to say, however, that your garden-variety Millicent has a fetish for identifying every speaker every time. As we have discussed, she regards the old-fashioned practice of including some version of he said with every speech as both old-fashioned and unnecessary. Which leads me to…

Including unnecessary tag lines: chant it with me now, campers: unless there is some genuine doubt about who is saying what when (as in the first line of text here), most tag lines (he said, she asked, they averred) aren’t actually necessary for clarity. Quotation marks around sentences are pretty darned effective at alerting readers to the fact that those sentences were spoken aloud. And frankly, unless tag lines carry an adverb or indicates tone, they usually don’t add much to a scene other than clarity about who is saying what when.

Most editors will axe unnecessary tag lines on sight — although again, the pervasiveness of tag lines in published books does vary from category to category. If you are not sure about the norms in yours, hie yourself hence to the nearest well-stocked bookstore and start reading the first few pages of books similar to yours. If abundant tag lines are expected, you should be able to tell pretty quickly.

Chances are that you won’t find many — nor would you in second or third novel manuscripts by published authors. Since most adult fiction minimizes their use, novelists who have worked with an editor on a past book project will usually omit them in subsequent manuscripts. So common is this self-editing trick amongst the previously published that to a well-trained Millicent or experienced contest judge, limiting tag line use is usually taken as a sign of professionalism.

Which means, in practice, that the opposite is true as well — a manuscript peppered with unnecessary tag lines tends to strike the pros as under-edited. Paragraph 2 of our example illustrates why beautifully: at the end of a five-line paragraph largely concerned with how Casey is feeling, wouldn’t it have been pretty astonishing if the speaker in the last line had been anybody but Casey?

The same principle applies to paragraph 4. Since the paragraph opens with Casey swallowing, it’s obvious that she is both the speaker and the thinker later in the paragraph — and the one that follows. (Although since a rather hefty percentage of Millicents frown upon the too-frequent use of single-line non-dialogue paragraphs — as I mentioned earlier in this series, it takes at least two sentences to form a narrative paragraph in English, technically — I would advise reserving them for instances when the single sentence is startling enough to warrant breaking the rule for dramatic impact. In this instance, I don’t think the thought line is astonishing enough to rise to that standard.)

Starting to see how Millicent considers a broad array of little things in coming up with her very quick assessment of page 1 and the submission? Although she may not spend very much time on a submission before she rejects it, what she does read, she reads very closely. Remember, agents, editors, and their screeners tend not to read like other people: instead of reading a page or even a paragraph before making up their minds, they consider each sentence individually; if they like it, they move on to the next.

All of this is imperative to keep in mind when revising your opening pages. Page 1 not only needs to hook Millicent’s interest and be free of technical errors — every line, every sentence needs to encourage her to keep reading.

In fact, it’s not a bad idea to think of page 1’s primary purpose (at the submission stage, anyway) as convincing a professional reader to turn the first page and read on. In pursuit of that laudable goal, let’s consider Millicent’s scrawl at the bottom of the page.

Having enough happen on page 1 that a reader can tell what the book is about: this is such a common page 1 (and Chapter 1) faux pas for both novel and memoir manuscripts that some professional readers believe it to be synonymous with a first-time submission. In my experience, that’s not always true. A lot of writers like to take their time warming up to their stories.

So much so, in fact, that it’s not all that rare to discover a perfectly marvelous first line for the book in the middle of page 4. Or 54.

How does this happen? As we’ve discussed earlier in this series, opening pages often get bogged down in backstory or character development, rather than jumping right into some relevant conflict. US-based agents and editors tend to get a trifle impatient with stories that are slow to start. (UK and Canadian agents and editors seem quite a bit friendlier to the gradual lead-in.) Their preference for a page 1 that hooks the reader into conflict right off the bat has clashed, as one might have predicted, with the rise of the Jungian Heroic Journey as a narrative structure.

You know what I’m talking about, right? Since the release of the first Star Wars movie, it’s been one of the standard screenplay structures: the story starts in the everyday world; the protagonist is issued a challenge that calls him into an unusual conflict that tests his character and forces him to confront his deepest fears; he meets allies and enemies along the way; he must grow and change in order to attain his goal — and in doing so, he changes the world. At least the small part of it to which he returns at the end of the story.

It’s a lovely structure for a storyline, actually, flexible enough to fit an incredibly broad swathe of tales. But can anybody spot a slight drawback for applying this structure to a novel or memoir?

Hint: you might want to take another peek at today’s example before answering that question.

Very frequently, this structure encourages writers to present the ordinary world at the beginning of the story as, well, ordinary — and the protagonist as similarly ho-hum The extraordinary circumstances to come, they figure, will seem more extraordinary by contrast. Over the course of an entire novel, that’s pretty sound reasoning (although one of the great tests of a writer is to write about the mundane in a fascinating way), but it can inadvertently create an opening scene that is less of a grabber than it could be.

Or, as I suspect is happening in this case, a page 1 that might not be sufficiently reflective of the pacing or excitement level of the rest of the book. And that’s a real shame, since I happen to know that something happens on page 2 that would make Millicent’s eyebrows shoot skyward so hard that they would knock her bangs out of place.

Those of you who like slow-revealing plots have had your hands in the air for quite a while now, haven’t you? “But Anne,” you protest, and not without justification, “I want to lull my readers into a false sense of security. That way, when the first thrilling plot twist occurs, it comes out of a clear blue sky.”

I can understand the impulse, lovers of things that go bump on page 3, but since submissions and contest entries are evaluated one line at a time, holding back on page 1 might not make the best strategic sense at the submission stage. Trust me, she’ll appreciate that bump far more if you can work it into one of your first few paragraphs.

Here’s an idea: why not start the book with it? Nothing tells a reader — professional or otherwise — that a story is going to be exciting than its being exciting right from the word go.

Bear in mind, though, that what constitutes excitement varies by book category. Yes, Millicent is always looking for an interesting protagonist facing an interesting conflict, but what that conflict entails and how actively she would expect the protagonist to react to it varies wildly.

But whether readers in your chosen category will want to see your protagonist weeping pitifully on a train track, fighting off lions bare-handed, or grinding her teeth when her boss dumps an hour’s worth of work on her desk at 4:59 p.m., you might want to invest some revision time in making sure your first page makes that conflict look darned fascinating — and that your protagonist seems like she’d be fun to watch work through it. Whatever your conflicts might be, keep up the good work!

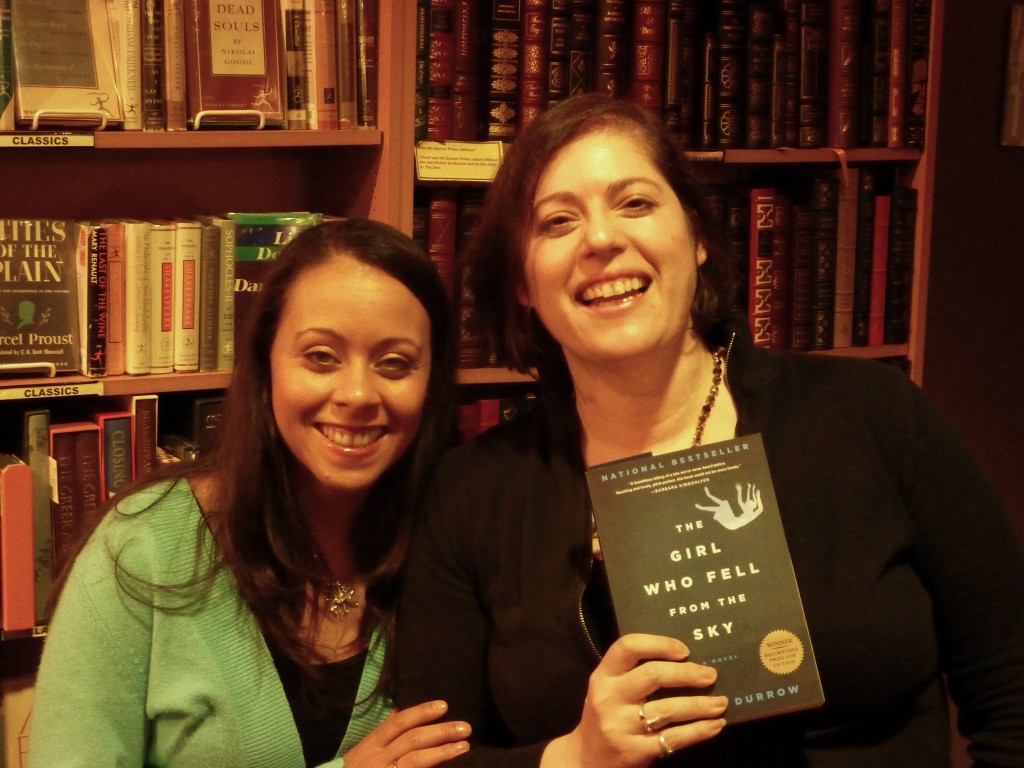

Rachel, the daughter of a Danish mother and a black G.I., becomes the sole survivor of a family tragedy after a fateful morning on their Chicago rooftop.

Rachel, the daughter of a Danish mother and a black G.I., becomes the sole survivor of a family tragedy after a fateful morning on their Chicago rooftop.

YA has its own distinctive conventions, particularly with respect to voice and subject matter. If it is not apparent from the first paragraph of page 1 that a manuscript is YA, even the best-written YA manuscript runs the risk of rejection on that ground alone.

YA has its own distinctive conventions, particularly with respect to voice and subject matter. If it is not apparent from the first paragraph of page 1 that a manuscript is YA, even the best-written YA manuscript runs the risk of rejection on that ground alone.