Jet lag does in fact go away sometime, doesn’t it? I’ve been home for several days now, and I’m still a bit out of it. Of course, that may be the result of a small part of my brain’s continuing to operate in French — specifically, the part that governs what I say to people who bump into me in grocery stores — while the rest is merrily going about its business in English.

Which is why, in case you’ve been wondering, I’ve been holding off on launching into my long-promised series on the ins and outs of formal writing retreats. The spirit is willing, but the connective logic is weak.

So brace yourself for a couple of segue posts, please, to move us from craft to artists’ colonies. In the great tradition of Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups, I’ll try to work in writing retreat examples into my discussions of craft, and craft tips into my treatment of retreats, to ease the transition.

In yesterday’s post, I covered a broad array of topics, ranging from voice to submission strategies to the desirability of learning something about one’s subject matter before writing about it. In the midst of a blizzard of advice on that last point, I mentioned in passing that when writers just guess at the probable life details and reactions of characters unlike themselves, they tend to end up with characters whose beauty and brains are inversely proportional, whose behavior and/or speech can be predicted as soon as the narrative drops a hint about their race/gender/sexual orientation/national origin/job/whatever, and/or who act exactly as though some great celestial casting director called up the nearest muse and said, “Hello, Euterpe? Got anything in a bimbo cheerleader?”

In other words, the result on the page is often a stereotype. And because, let’s face it, since television and movies are the happy hunting ground of stereotypes, writers may not necessarily even notice that they’ve imbibed the odd cliché.

A pop quiz for long-time readers of this blog: why might that present a problem in a manuscript submission? For precisely the same reason that a savvy submitter should avoid every other form of predictability in those first few pages: because Millicent the agency screener tends not to like it.

Even amongst agents, editors, and judges who are not easily affronted, stereotypes tend not to engender positive reactions. What tends to get caught by the broom of a sweeping generalization is not Millicent’s imagination, but the submission. If it seems too stereotypical, it’s often swept all the way into the rejection pile.

Why, you ask? Because by definition, a characterization that we’ve all seen a hundred times before, if not a thousand, is not fresh. Nor do stereotypes tend to be all that subtle. And that’s a problem in Millicent’s eyes, because in a new writer, what she’s really looking to see is originality of worldview and strength of voice, in addition to serious writing talent.

When a writer speaks in stereotypes, it’s extremely difficult to see where her authorial voice differs markedly from, say, the average episodic TV writer’s. It’s just not all that impressive — or, frankly, all that memorable.

I’m bringing this up today in part because yesterday’s post talked so much about the perils of writing the real, either in memoir form or in the ever-popular reality-thinly-disguised-as-fiction tome. Many, many people, including writers, genuinely believe various stereotypes to be true; therein lies the power of a cliché. The very pervasiveness of certain hackneyed icons in the cultural lexicon — the dumb jock, the intellectually brilliant woman with no social skills, the morals-deficient lawyer, the corrupt politician, to name but four — render them very tempting to incorporate in a manuscript as shortcuts, especially when trying to tell a story in an expeditious manner.

Don’t believe me? Okay, which would require more narrative description and character development, the high school cheerleader without a brain in her head, or the one who burns to become a nuclear physicist? At this point in dramatic history, all a pressed-for-time writer really has to do is use the word cheerleader to evoke the former for a reader, right?

Unless, of course, a submission that uses this shortcut happens to fall upon the desk of a Millicent who not only was a high school cheerleader, but also was the captain of the chess team. At Dartmouth. To her, a manuscript that relies upon the usual stereotype isn’t going to look as though it’s appealing to universal understandings of human interaction; it’s going to come across as a sweeping generalization.

Can you really blame her fingers for itching to reach for the broom?

Interestingly, when Millicents, their boss agents, and the editors to whom they cater gather to share mutual complaints in that bar that’s never more than 100 yards from any writers’ conference in North America, it’s not just the common stereotypes that tend to rank high on their pet peeve lists. The annoying co-worker, however defined, crops up just as often.

Why, you ask? Well, for several reasons, chief among which is that every writer currently crawling the crust of the earth has in fact had to work with someone less than pleasant at one time or another. That such unsavory souls would end up populating the pages of submissions follows as night the day.

If these charming souls appeared in novel and memoir submissions in vividly-drawn glory, that actually might not be a problem. 99% of the time, however, the annoying co-worker is presented in exactly the same way as a stereotype: without detail, under the apparent writerly assumption that what rankles the author will necessarily irk the reader.

Unfortunately, that’s seldom the case — it can take a lot of page space for a character to start to irritate a reader. So instead of allowing the character to demonstrate annoying traits and allowing the reader to draw her own conclusions, many a narrative will convey that a particular character is grating by telling the reader directly (“Georgette was grating”), providing the conclusion indirectly (through the subtle use of such phrases as, “Georgette had a grating voice that cut through my concentration like nails on a chalkboard”), or through the protagonist’s thoughts (“God, Georgette is grating!”)

Pardon my asking, but as a reader, I need to know: what about Georgette was so darned irritating? For that matter, what about her voice made it grating? It’s the writer’s job to show me, not tell me, right?

I cannot even begin to count the number of novels I have edited that contained scenes where the reader is clearly supposed to be incensed at one of the characters, yet it is not at all apparent from the action of the scene why. Invariably, when I have asked the authors about these scenes, they turn out to be lifted directly from real life. (No surprise there: these scenes are pretty easy for professionals to spot, because the protagonist is ALWAYS presented as in the right for every instant of the scene, a state of grace quite unusual in real life. It doesn’t ring true.)

The author is always quite astonished that his own take on the real-life scene did not translate into instantaneous sympathy in every conceivable reader. Ultimately, this is a point-of-view problem — the author is just too close to the material to be able to tell that the scene doesn’t read the way he anticipated.

Did I just see some antennae springing up out there? “Hey, wait a minute,” alert readers of yesterday’s post are muttering just about now, “isn’t this sort of what Edith Wharton was talking about yesterday? Mightn’t an author’s maintaining objective distance from the material — in this case, the annoying co-worker — have helped nip this particular problem in the bud long before the manuscript landed on Millicent’s desk?”

Why, yes, now that you mention it, it would. What a remarkable coincidence that she and I should have been discussing this on consecutive days.

Let’s look at the benefits of some objective distance in action. Many writers assume (wrongly) that if someone is irritating in real life, and they reproduce the guy down to the last whisker follicle, he will be annoying on the page as well, but that is not necessarily true. Often, the author’s anger so spills into the account that the villain starts to appear maligned, from the reader’s perspective. If his presentation is too obviously biased, the reader may start to identify with him, and in the worst cases, actually take the villain’s side against the hero. I have read scenes where the case against the villain is so marked that most readers would decide that the hero is the impossible one, not the villain.

This character assassination has clearly not gone as planned. A little more objective distance might have made it go better. Who was it that said, revenge is a dish best served cold?

Yes, I called it revenge, because revenge it usually is. Most writers are very aware of the retributive powers of their work. As my beloved old mentor, the science fiction writer Philip K. Dick, was fond of saying, “Never screw over a living writer. They can always get back at you on the page.”

Oh, stop blushing. You didn’t honestly think that when you included that horrible co-worker in three scenes of your novel that you were doing her a FAVOR, did you?

My most vivid personal experience of this species of writerly vitriol was not as the author, thank goodness, but as the intended victim. And at the risk of having this story backfire on me, I’m going to tell you about it as nonfiction.

Call it a memoir excerpt.

More years ago than I care to recall, I was in residence at an artists’ colony. (See? I told you I was going to work in an example from a writers’ retreat!) Now, retreats vary a great deal; mine have ranged from a fragrant month-long stay in a cedar cabin in far-northern Minnesota, where all of the writers were asked to remain silent until 4 p.m. each day (ah, dear departed Norcroft! I shall always think of you fondly, my dear – which is saying something, as I had a close personal encounter with an absolutely mammoth wolf there, and a poet-in-residence rode her bicycle straight into a sleepy brown bear. And both of us would still return in an instant) to my recent sojourn in a medieval village in southwestern France to a let’s-revisit-the-early-1970s meat market, complete with hot tub, in the Sierra foothills.

Had I mentioned that it pays to do your homework before you apply?

This particular colony had more or less taken over a small, rural New England town, so almost everyone I saw for a month was a painter, a sculptor, or a writer. The writers were a tiny minority; you could see the resentment flash in their eyes when they visited the painters’ massive, light-drenched studios, and compared them to the dark caves to which they had been assigned.

I elected to write in my room, in order to catch some occasional sunlight, and for the first couple of weeks, was most happy and productive there. Okay, so sharing meals in a dining hall was a bit high school-like, conducive to tensions about who would get to sit at the Living Legend in Residence’s table, squabbles between the writers and the painters about whether one should wait until after lunch to start drinking, or break out the bottles at breakfast (most of the writers were on the first-mentioned team, most of the painters on the latter), and the usual bickerings and flirtations, serious and otherwise, endemic to any group of people forced to spend time together whether or not they have a great deal in common.

An environment ripe, in other words, for people to start to find their co-residents annoying.

Now, one classic way to deal with the inevitable annoying co-resident problem is to bring a buddy or three along on a retreat; that way, if the writer in the next cubicle becomes too irritating, one has some back-up when one goes to demand that she stop snapping her gum every 27 seconds, for Pete’s sake. Personally, when I go on a writing retreat, I like to leave the trappings of my quotidian life behind, but there’s no denying that at a retreat of any size, there can be real value in having someone to whom to vent about that darned gum-popper. (Who taught her to blow bubbles? A horse?)

Doubtless for this reason, several artists had brought their significant others to the New England village retreat — or, to be more accurate, these pairs had applied together: writer and photographer, painter and writer, etc. (Generally speaking, one of the tell-tale differences between a serious artists’ retreat and a casual one is whether you have to write, paint, sculpt, or photograph your way in; at a retreat that takes just anyone, the application will not require you to submit any of your work.)

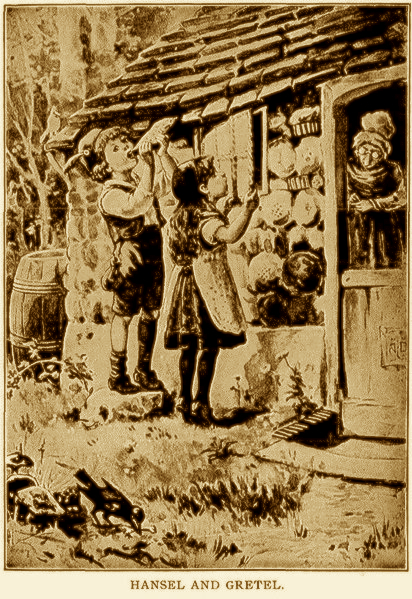

One of these pairs was a very talented young couple, she a writer brimming with potential, he a sculptor of great promise. Although every fiber of my being longs to use their real names, I shall not. Let’s call them Hansel and Gretel, to remove all temptation.

Hansel was an extremely friendly guy, always eager to have a spirited conversation on topics artistic or social. Actually, he was sort of the dining hall’s Lothario, flirting with…hmm, let’s see how best to represent how he directed his attentions…everything with skin. In fairness to him, none of the residents was all that surprised that he often brought the conversation around to sex; honestly, once you’d seen his sculpture studio packed with representations of breasts, legs, pudenda, buttocks, and breasts, you’d have to be kind of dense not to notice where his mind liked to wander.

Being possessed of skin myself, I was naturally not exempt from his attentions, but generally speaking, I tend to reserve serious romantic intentions for…again, how to put this…people capable of talking about something other than themselves. Oh, and perhaps I’m shallow, but I harbor an absurd prejudice in favor of the attractive.

An artists’ retreat tends to be a small community, however; one usually ends up faking friendliness with an annoying co-resident or two. Since there was no getting away from the guy — believe me, I tried — I listened to him with some amusement whenever we happened to sit at the same table. I loaned him a book or two. We had coffee a couple of times when there was nobody else in the town’s only coffee shop. And then I went back to my room and wrote for 50 hours a week.

Imagine my surprise, then, when Gretel started fuming at me like a dragon over the salad bar. Apparently, she thought I was after her man.

Now, I don’t know anything about the internal workings of their marriage; perhaps they derived pleasure from manufacturing jealousy scenes. I don’t, but there’s just no polite way of saying, “HIM? Please; I DO have standards” to an angry wife, is there? So I started sitting at a different table in the dining hall.

A little junior high schoolish? Yes, but better that than Gretel’s being miserable — and frankly, who needed the drama? I was there to write.

Another phenomenon that often characterizes a mixed residency — i.e., one where different types of artists cohabitate — is a requirement to share one’s work-in-progress. At this particular retreat, the fellowship that each writer received included a rule that each of us had to do a public reading while we were in residence.

Being a “Hey – I’ve got a barn, and you’ve got costumes!” sort of person, I organized other, informal readings as well, so we writers could benefit from feedback and hearing one another’s work. I invited Gretel to each of these shindigs; she never came. Eventually, my only contact with her was being on the receiving end of homicidal stares in the dining hall, as if I’d poisoned her cat or something.

It was almost enough to make me wish that I HAD flirted with her mostly unattractive husband.

But I was writing twelve hours a day (yes, Virginia, there IS a good reason to go on a retreat!), so I didn’t think about it much. I had made friends at the retreat, my work was going well, and if Gretel didn’t like me, well, we wouldn’t do our laundry at the same time. (You have to do your own laundry at every artists’ retreat on earth; don’t harbor any fantasies about that.) My friends teased me a little about being such a femme fatale that I didn’t even need to do anything but eat a sandwich near the couple to spark a fit of jealous pique, but that was it.

At the end of the third week of our residency, it was Gretel’s turn to give her formal reading to the entire population of the colony, a few local residents who wandered in because there was nothing else to do in town, and the very important, repeated National Book Award nominee who had dropped by (in exchange for a hefty honorarium) to shed the effulgence of her decades of success upon the resident writers. Since it was such a critical audience, most of the writers elected to read highly polished work, short stories they had already published, excerpts from novels long on the shelves. Unlike my more congenial, small reading groups, it wasn’t an atmosphere conducive to experimentation.

Four writers were scheduled to read that night. The first two shared beautifully varnished work, safe stuff, clearly written long before they’d arrived at the retreat. Then Gretel stood up and announced that she was going to read two short pieces she had written here at the colony. She glanced over at me venomously, and my guts told me there was going to be trouble.

How much trouble, you ask with bated breath? Well, her first piece was a lengthy interior monologue, a first-person extravaganza describing Hansel and Gretel — both mentioned by name on page 1, incidentally — having sex in vivid detail. Just sex, without any emotional content to the scene, a straightforward account of a mechanical act which included – I kid you not – a literal countdown to the final climax: “Ten…nine…eight…”

It was so like a late-1960’s journalistic account of a rocket launching that I kept expecting her to say, “Houston, we’ve got a problem.”

I cringed for her — honestly, I did. I have no objection to writers who turn their diaries into works for public consumption, but this was graphic without being either arousing or instructive. I’d read some of Gretel’s other work: she was a better writer than this. So what point was she trying to make by reading this…how shall I put it?…literarily uninteresting junk?

Maybe I just wasn’t the right audience for her piece: the painters in the back row, the ones who had been drinking since breakfast, waved their bottles, hooting and hollering. Still, looking around the auditorium, I didn’t seem to be the only auditor relieved when it ended. (“Three…two…one.”) Call me judgmental, but I tend to think that when half the participants are pleased the act is over, it’s not the best romantic coupling imaginable.

Gretel’s second piece took place at a wedding reception. Again, it was written in the first person, again with herself and her husband identified by name, again an interior monologue. However, this had some legitimately comic moments in the course of the first few paragraphs. As I said, Gretel could write.

Somewhere in the middle of page 2, a new character entered the scene, sat down at a table, picked up a sandwich – and suddenly, the interior monologue shifted from a gently amused description of a social event to a jealously-inflamed tirade that included the immortal lines, “Keep away from my husband, bitch!” and “Are those real?”

Need I even mention that her physical description of the object of these jabs would have enabled any police department in North America to pick me up right away?

She read it extremely well; her voice, her entire demeanor altered, like a hissing cat, arching her back in preparation for a fight. Fury looked great on her. From a literary standpoint, though, the piece fell flat: the character that everyone in the room knew perfectly well was me never actually said or did anything seductive at all; her mere presence was enough to spark almost incoherent rage in the narrator. While that might have been interesting as a dramatic device, Gretel hadn’t done enough character development for either “Gretel” or “Jan”– cleverly disguised name, eh?– for the reader either to sympathize with the former or find the latter threatening in any way.

There was no ending to the story. She just stopped, worn out from passion. And Hansel sat there, purple-faced, avoiding the eyes of his sculptor friends, until she finished.

The first comment from the audience was, “Why did the narrator hate Jan so much? What had she done to the narrator?”

I was very nice to Gretel afterward; what else could I do? I laughed at her in-text jokes whenever it was remotely possible, congratulated her warmly on her vibrant dialogue in front of the National Book Award nominee, and made a point of passing along a book of Dorothy Parker short stories to her the next day.

Others were not so kind, either to her or to Hansel. The more considerate ones merely laughed at them behind their backs. (“Three…two…one.”) Others depicted her in cartoon form, or acted out her performance; someone even wrote a parody of her piece and passed it around.

True, I did have to live for the next week with the nickname Mata Hari, but compared to being known as the writer whose act of fictional revenge had so badly belly flopped, I wouldn’t have cared if everyone had called me Lizzie Borden. And, of course, it became quite apparent that every time I went out of my way to be courteous to Gretel after that, every time I smiled at her in a hallway when others wouldn’t, I was only pouring salt on her wounded ego.

Is there anything more stinging than someone you hate feeling sorry for you?

If your answer was any flavor of yes, you might want to consider waiting until you’ve developed some objective distance from your annoying co-worker before committing her to print. Think at least twice about what you’re putting on the page, particularly for work you are submitting to contests, agencies, or small presses – or, heaven forbid, reading to a group of people you want to like you, or at any rate your narrator.

Believe me, revenge fantasies tend to announce themselves screamingly from the page, at least to a professional reader. If you’re still angry, maybe it’s not the right time to write about it for publication. Your journal, fine. But until you have gained some perspective — at least enough to perform some legitimate character development for that person you hate — consider giving it a rest. Otherwise, your readers’ sympathies may ricochet, and move in directions that you may not like.

It’s always a good idea to get objective feedback on anything you write before you loose it on the world, but if you incorporate painful real-life scenes into your fiction, sharing before promotion becomes ABSOLUTELY IMPERATIVE. If you work out your aggressions at your computer — and, let’s face it, a lot of us do — please, please join a writing group.

To be blunt about it, finding good first readers you can trust can save you from looking like an irate junior high schooler on a rampage.

And Gretel, honey, in the unlikely event that you ever read this, you might want to remember: revenge is a dish best served cold. Or, as Philip used to say, never screw over a living writer. You never know who might end up writing a blog.

Hey, I’m only human. Which is precisely why I wasn’t writing blog posts on my most recent retreat while I was in residence. It can take some time — and in this case, distance, judging by my lingering jet lag — to gain perspective.

Keep up the good work!