Of all the many, many mysteries that keep those of us who handle manuscripts for a living up at night, none is so recalcitrant — and, even more trying to the editorial mind, positively immune to diagnostic analysis — than why it so often seems to come as a complete surprise to memoirists to be asked, “What’s your book about?” From a publishing perspective, few questions could be more straightforward, or more predictable: presumably, something occurred in the memoirist’s life that he thought would make a good story on paper, right?

To your garden-variety memoirist, however, answering this inherently loaded question is complicated. Or so publishing professionals surmise, from the long pause that typically ensues. Often preceded by a gusty sigh and succeeded by a sudden avalanche of seemingly unrelated personal anecdotes.

That’s the standard response, by the way, regardless of the context in which a memoirist is asked what her book is about. Be it at a writers’ conference, in a social interaction at the bar that’s never more than a hundred yards from any writers’ conference in North America, at a party mostly peopled by non-writers (oh, we do manage to mingle occasionally), or even in a pitch meeting, people writing about their own lives tend to change the subject. Rather quickly, too.

If you’ll forgive my saying so, memoirists, that’s a pretty remarkable reaction, at least to those of us prone to hanging out with writers. Published and as-yet-to-be published writers are notoriously fond of talking about their work, sometimes to the exclusion of actually working on new projects. Heck, there’s even an old joke about it:

Aspiring writer at cocktail party: I hear you’re an agent. I’ve written a book…

Agent (instantly scoping the exits): I’d love to hear about it, but I’m afraid I have only an hour left to live.

Hey, I didn’t say it was a good joke, but it is reflective of the way the rest of the world views writers. A writer’s will to communicate tends to be pretty strong, after all; even a shy writer will often burst into chattiness when given the slightest encouragement to talk about his work-in-progress. So it just doesn’t make sense to the rest of the human population when someone writing about what should be the most absorbing topic of all, dear self, doesn’t seem to want to talk about it.

Indeed, from the intensity of that sigh that’s always blowing those of us kind enough to inquire over sideways, the mere mention of it seems to be quite painful. As a memoirist myself, someone who recently wrote an explanatory introduction for somebody else’s memoir, a lifetime interview subject for biographies about the famous and semi-famous (I’d tell you about it, but that would involve blurting out my life story; oh, the pain), and a frequent editor of memoir, I think I can tell you why.

What we have hear, my friends, is a failure to communicate. What a memoir-writer hears is not the question, “So what is your book about, anyway?” but something closer to, “Sum up your life in fifty words or less. Kindly include a brief summary of the meaning of life in general while you are at it. Please bear in mind that how you will be remembered after your death rides on this answer. Ready — go!”

Just so you know, writers of the real: that’s not what’s being asked here. The Inquisition is not breaking out the thumbscrews, demanding a confession. Not at a cocktail party, not at a writers’ conference, and certainly not when anyone that might conceivably be able to help you get your memoir published brings it up.

So what are these fine folks asking? Precisely what they would ask any other writer. What they are hoping to hear is a short, cogent summary of your book’s story arc.

Imagine their surprise, then, when the memoirist abruptly clams up. Or starts muttering into her drink a shaggy dog tale about the summer of 1982 — a particularly effective evasive technique, as 1982 was for so many of us a year best forgotten altogether.

And those are the courteous responses. Sometimes, the well-meaning questioner will merely elicit a begrudging snort of, “Well, obviously, it’s about me.”

Of course, any prospective author is perfectly at liberty to shorten her list of friends to contact when her book comes out — oh, you thought the recipient of such a dismissive answer was going to break down the doors of his local indie bookseller to buy that memoir? — but you’d be astonished at how frequently agents and editors hear this type of comeback. Without, apparently, anticipating that the response to it will not be particularly gratified, “Well, thanks for filling me in, Noah Webster. Twenty years in publishing, and I had yet to learn the definition of memoir.”

Okay, so most publishing types’ mothers taught them not to be this rude to relative strangers. To the pros, though, any of these replies is perplexing, at best, and at worst, a sign of a complete misunderstanding of how and why anyone not already personally connected with an author might become interested in a memoir.

They have a point, practically speaking. To those who have never tackled the difficult and emotionally-draining task of writing their own stories, it’s well-neigh incomprehensible that anyone hoping to sell a manuscript or proposal could not instantly answer what is, after all, a question any agent representing the book, any editor acquiring the book, any publicist pushing the book, and any reader remotely likely to pick up the book would need to know right off the bat. Surely, having a story to tell is a prerequisite to telling it.

So how could one hope to market a book without knowing what it was about? Heck, how could one hope to write a book without having a clear idea of its story arc?

Actually, those questions puzzle most fiction writers, too, as well as the people that love them. Oh, novelists are not immune to that lengthy hesitation — combined, nine times out of ten, with a gusty sigh — in response to the more general, “So what do you write?” Yet fiction-writers usually manage to follow up with an account that bears at least some embryonic resemblance to the plots of their books.

Astonishingly often, though, memoirists do not — and sometimes seemingly cannot, even if they have already successfully proposed their books. Take Diane, for instance, a courageous memoirist who has recently sold a searing tale of self-revelation to a major publisher; she said that I could share her experience here on condition of changing her name, age, sex, height, weight, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, profession, familial background, and any other identifier that might conceivably render her recognizable to anyone she has ever known. Particularly her book’s acquiring editor.

A truly gifted anecdotalist, Diane has lead a remarkable life (about which I can, of course, tell you nothing); a skilled writer with substantial journalism experience (oops), she is likely to tell it well. Being familiar with how the publishing industry works, she had little trouble pulling together a book proposal, tossing off the requisite marketing materials in three weeks and polishing off a gem of a sample chapter in six. Her agent, Tyrone, fell in love with what was for Diane a new type of writing and was able to sell the book to an eager editor within a remarkably short time to Grace, a very talented editor with a great track record of handling personal memoir with aplomb.

The publication contract specified a not unusually short time in which to complete the manuscript: six months.

Well might you choke, memoirists. At that point, Diane had written only the sample chapter and the first three paragraphs of Chapter 2.

As is all too easy for those new to the game to forget, a book proposal is a job application: the writer makes the case that she is the best person currently occupying the earth’s crust to write a particular book, right? Implicit in that case, however, is the expectation that she will be able to produce that book by a deadline.

None of this was news to Diane, of course, at least not at an intellectual level. She knew that she was a fairly typical position for a first-time memoirist: she would need to write the book she had proposed on a not-unreasonable deadline — or what would have been a reasonable deadline, were advances still large enough to take time off work to complete a writing project. Not necessarily the easiest task in the world, certainly, given that it had taken her six weeks of nights and weekends to compose that nice sample chapter; at the rate she had been writing so far, it would only take another two years to write the book as she had conceived it.

But she did not have two years; she had six months. And Grace had, as acquiring editors of nonfiction so often do, asked for a few changes to the book’s proposed running order. As well as some minor tweaks to the voice.

Does the monumental gasp that just shook a nearby forest indicate that some of you memoirists were not aware that could happen? If so, you’re not alone: since writers so often work in isolation, it’s not at all uncommon for a first-time book proposer to forget (or not to know in the first place) that since the proposal is a job application for the position of writing the book, the publisher hiring the writer generally has the contractual right to ask for changes in that book. And that can be awfully difficult for personal memoirists, who have often spent years working up the nerve to write their life stories in the first place, much less to someone else’s specifications.

Fortunately, Tyrone had experience working with first-time memoirists; he had the foresight to warn Diane before he started circulating the book proposal that the book she had in mind might not be what precisely the acquiring editor would like to see in the published version. So when Diane received the news that Grace felt that the storyline was getting a little lost in the welter of chapters proposed in the Annotated Table of Contents.

“Just stick to the book’s major story arc,” she said, “and we’ll be fine. If this book sells well, we can always work the other material into your next.”

Stop that sighing, memoirists. The furniture in my studio is only battened down to the level appropriate for earthquakes, not hurricanes.

Still, Diane had worked on short deadlines before, and this one was not all that short. Besides, Grace clearly knew what she was talking about; she had spotted a legitimate flaw in the Annotated Table of Contents. Diane hadn’t really thought much about the structure of the book, beyond simply presenting what had happened to her in chronological order. Streamlining her story a little should not be all that hard, right?

Her opinion on the subject shifted slightly over the next three months: writing a personal memoir is notoriously prone to stirring up long-dead emotions. The brain does not seem to make a very great distinction between reliving an event vividly enough to write about it well and living through a current event. Understandably, Diane felt as though she had been going through intensive therapy in her spare time, on a deadline, while holding a full-time job.

Now, Diane saw her previously-manageable task as a gargantuan one. Presuming that she had the stamina to finish drafting the book by her ever-nearing deadline, something she was beginning to doubt was humanly possible, would she be writing it as she wished, or would she simply end up throwing words onto paper? Under those unreasonable circumstances, how could she possibly maintain sufficient perspective on that terrible period of her life to come up with a satisfying dramatic arc? She felt she would be lucky just to get the whole story into a Word file on time.

So she did what most first-time memoirists do: she just wrote the story of that period of her life in chronological order. She wasn’t altogether happy with the manuscript, but she did get it to Grace before the deadline.

Hard to blame her for embracing that tactic, isn’t it? Most of us don’t think of our own lives as having a story arc. We live; things happen; if we’re self-aware, we might occasionally learn something from the process. And when we talk about our lives out loud, that’s not much of a storytelling barrier: verbal anecdotes don’t require much specific detail, character development, or ongoing plot.

Nor does sentence structure typically make or break an anecdote. Summary statements can work just fine. Indeed, it’s not unheard-of for every sentence of a perfectly marvelous anecdote to begin with the phrase I was…

Unfortunately, as Grace pointed out to Diane after the first draft had winged its merry way to the publishing house, that particular type of storytelling, while fine in the right context, just doesn’t fly on the printed page. Memoir readers expect fully fleshed-out scenes, complete with dialogue; too many summary statements back-to-back can start to seem, well, vague. Could the text be more specific?

Then, too, just referring to a major character as my brother was going to get awfully tedious awfully fast for a reader; Diane was going to have to do some character development for the guy. Like, for instance, letting the reader know what he looked like and why, if he lived in Bolivia, he seemed to be dropping by her apartment in Chicago on every ten pages.

Oh, and while Diane was at it, could she be a trifle more choosy about what was and was not important enough to the central story arc to keep on the page? “I raised this concern about the proposal,” Grace pointed out, and rightly. “I know it’s hard to think about yourself as a protagonist in a book, but you have to remember that is how the reader is going to think of you. While a side story might seem vital to how you, a member of your family, or one of your friends would recall this part of your life, you’re not writing the story for people who already know it.”

While this was, from a professional perspective, pretty terrific advice — after all, the art of memoir consists as much in deciding what to leave out as in what to include — Diane felt overwhelmed by it, as well as by her two-month revision deadline. Completely understandable, right? Here she was, frantically rewriting some of her favorite passages and slashing others (oh, her mother would be furious to see her favorite scene in Chapter 5 go!), and now that Grace had forced her to contemplate it, she had to admit that she still had no clear notion of what the overall message of that period of her life was. Why wasn’t it enough to present what actually happened, directly and honestly?

Come to think of it, wasn’t it just a touch dishonest to cut out things that had actually happened? Didn’t she owe it to the reader to give a complete picture, even if that meant boring Grace a little? Wasn’t it compromising her vision as an author to mold her work to the specifications of an editor who was…oh, my God, was Grace asking her to change the story of her life?

Naturally, she wasn’t asking any such thing, as I told Diane when she called me in a panic. Grace, like all conscientious editors, was merely being the reader’s advocate: prodding the writer to make the reading experience as entertaining and absorbing as possible on the printed page.

Need you sigh with such force, memoirists? You just blew my cat across the room. “But Anne,” some of you protest, “doesn’t Diane have a pretty good point here? She had envisioned her story a particular way, crammed with everyday detail. That kind of slice-of-life writing can be very effective: I like a memoir that makes me feel that I’m inhabiting the narrator’s world. So isn’t she right to fight tooth and nail for her earlier draft?”

Ah, that’s often a writer’s first response to professional feedback: to regard it as inherently hostile to one’s vision of the book, rather than as practical advice about how to present that vision most effectively. But that’s usually not what’s going on — and it certainly wasn’t in this case. Grace was genuinely trying to make the book a better read.

And, frankly, she was right about limiting the proportion of the book devoted to depicting Diane’s everyday life vs. the extraordinary events that interrupted it. Grace believed, and with good reason, that as a non-celebrity memoir, the audience for this book would be drawn far more to the dramatic, unique parts of the story than to the parts that dealt with ordinary life. Let’s face it, just as everyday dialogue would be positively stultifying transcribed to the novel page , quite a lot of what occurs in even the most exciting life would not make for very thrilling reading.

Oh, you thought that “Some weather we’re having.” “Yeah. Hot enough for you?” “Sure could use some rain.” was going to win you the Pulitzer? Grace was quite right in maintaining that the art of memoir very largely lies in selecting what to leave out — and that Diane’s very gripping first-person narrative was getting watered down by too many scenes about…

Wait, what were they about? It was hard for the reader to tell; they seemed to be on the page simply because they had happened.

I know, I know: that’s not an entirely unreasonable selection criterion for, say, a blog. As the Internet has demonstrated time and again, people like to get a peek into other people’s lives. That does not mean, however, there’s a huge book-reading audience out there potentially fascinated with what any given writer had for breakfast, his interactions with his cat, and how he sweeps dried mud from his shoes.

Sort of seems like sacrilege to say it, given how the media tends to celebrate the Twitterverse these days, doesn’t it? Yes, there are plenty of venues where it is perfectly acceptable — nay, encouraged — to share even the smallest details of one’s personal life, but by and large, strangers do not pay to find out what Writer X had for lunch today.

Oh, sure, your Facebook friends might like to hear about it, but it’s hard to imagine plowing through 400 pages of printed-out status updates, isn’t it? I hope it has not escaped your notice, memoirists, that by and large, the people vitally interested in those day-to-day specifics are not total strangers, but those who already know you personally.

In case I’m being too subtle here: the no doubt well-deserved loving attention of your kith and kin to the contrary, writing down everything that happens to you seldom works in a book. Real life is too random, and, frankly, it’s lousy at plot development.

Indeed, reality is not always even particularly believable, at least on the page. As Mark Twain liked to say — wow, I’ve been quoting hi a lot lately, have I not? — truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities. Truth isn’t.

Sorry to break that to those of you who had been following those gusty sighs with, “Well, this really happened to me.” Of course it did. You’re writing a memoir. The mere fact that you lived it doesn’t excuse you from making it one heck of a great read, does it?

Or, to put it another way, the simple fact that something really happened does not render it inherently interesting for a reader; that’s the writer’s job. Agents and editors like to say that it all depends on the writing, but for a memoir, I would add that it also depends upon understanding what is and is not essential to the story you’re telling.

The reader does not need to know what every cobblestone on the street looked like in order to be thrilled by the scene when bloodhounds chased you from one end of that street to the other. (Oh, did I bury the lead there? That’s also a pretty common problem in memoir manuscripts: the most important element is hidden in the middle of a paragraph ostensibly about something else. Rather like this piece of advice: annoying for a skimmer, isn’t it?) To entice a reader to keep following a protagonist, real or not, through hundreds of pages, a narrative needs to convey a sense of forward motion based upon dramatic development, not just the progression of time.

“But Anne!” social media enthusiasts shout, and who could blame you? “Celebrities tweet about mundane personal details all the time, and I’ve heard that publicists tell the famous point-blank that posting about real-like activities (especially with pictures!) is one of the best ways to build up a social media following. People like to feel they are in the know — and while we could quibble about whether anything said to People magazine could be construed as private, there’s certainly a demonstrable market for it. So while I agree that quite a lot of it is stultifying, both on the screen and on the printed page, you can’t deny that celebrity memoir often does get down to the what-I-ate-for-breakfast level. And those books sell.”

Good point, enthusiasts, but from a publishing point of view, celebrity memoirs that dwell upon the ordinary sell despite containing ho-hum specifics, not because of them. What causes a reader to pick up the book is already being familiar with the author, at least by reputation. The ability to draw that type of instant recognition is integral to a celebrity author’s platform.

I hear some of you grumbling about how celebrity-chasing limits the number of publishing slots available for non-celebrity memoir, but honestly, public attraction to the private lives of celebrities is hardly a recent development. Cartoons of Marie Antoinette’s alleged palace escapades were hot sellers in the years leading up to the first French Revolution. A satire of Julius Caesar’s relationship with a prince he’d bested in battle enjoyed wide circulation. Cleopatra’s P.R. people worked overtime not to get the word out that, unlike her dim-witted brother, she spoke so many languages that she could conduct treaty discussions with foreign dignitaries herself, but to convince regular folk to regard her as the incarnation of Aphrodite. Just ask the hundreds of spectators who showed up to watch her have dinner on a boat with the earthly embodiment of the war god, Marc Antony.

I venture to say, however, that just because the world is evidently stuffed with people willing to read half a page about a celebrity’s breakfast-eating habits because they hope that the following page will talk about something more glamorous, it does not render that half a page inherently exciting. Unless the celebrity in question happens to wake up one day and decides to consume something genuinely remarkable — like, say, an elephant or the cornerstone to the Chrysler Building — it’s just ordinary stuff.

I say this, incidentally, as someone who regularly gets accosted by biographers trying to find out what certain literary luminaries preferred in a breakfast cereal. Which just goes to show you: the more famous a writer becomes, the more likely he is to be judged by something other than his writing.

There are, of course, quite a few genuinely interesting and well-written celebrity memoirs and biographies; I don’t mean to cast aspersions on those book categories. I’m merely suggesting that it might be quite a bit easier for someone who already has a national platform to get an ordinary breakfast table scene published than it would be for anyone else.

Like, say, Diane. I think that Grace was doing her a favor, actually: most memoir readers would be more critical than she of a memoir that got bogged down in mundanties. When is it better for a writer to hear a hard truth like that, do you think — early enough in the publication process that she can do something about it, or after the book comes out, in the online reviews?

Speaking as a person who would rather identify and nip problems in the bud, rather than the more popular tactics of ignoring them or waiting until they have grown into trees to chop them down, I must admit that I’m a big fan of the former. Yes, it’s nice to hear nothing but praise of one’s writing, but to improve it, trenchant critique is your friend.

Which, I am happy to report, Diane did quickly come to realize. Grace’s revision requests were not unreasonable; they were aimed at making the story they both loved more marketable. Together, they managed to come up with a final version that this reader, at least, found pretty compelling. Streamlined to within an inch of its life.

What may we conclude from Diane’s story? Perhaps nothing; like so many real-life sagas, it may well be just a series of events from which a bystander can learn little. It’s also possible, I suppose, that this tale was just my heavy-handed, editorial-minded way of saying hey, writers, you might want to consider the possibility that your editor is right. It has been known to happen, you know, and far more frequently than revision-wary aspiring writers tend to presume before their work has had the benefit of professional feedback.

No doubt due to my aforementioned fondness for tackling writing problems as soon as they pop their green shoots above ground, I believe that Diane’s problem evolved from that lengthy pause and gusty sigh after being asked, “So what is your book about?” Like the overwhelming majority of first-time memoirists, she simply hadn’t thought about it much — not, that is, until writing on a deadline and to a publishing house’s expectations forced her to contemplate the issue.

So in the interest of saving you chagrin down the line, I ask you, memoirists: what is your book about? What is its essential story arc? And how can you sift through the myriad events of your fascinating life to present it to the reader as fascinating?

Why, yes, those are some mighty big questions, now that you mention it. Would I really be doing your book a favor if I asked easier ones?

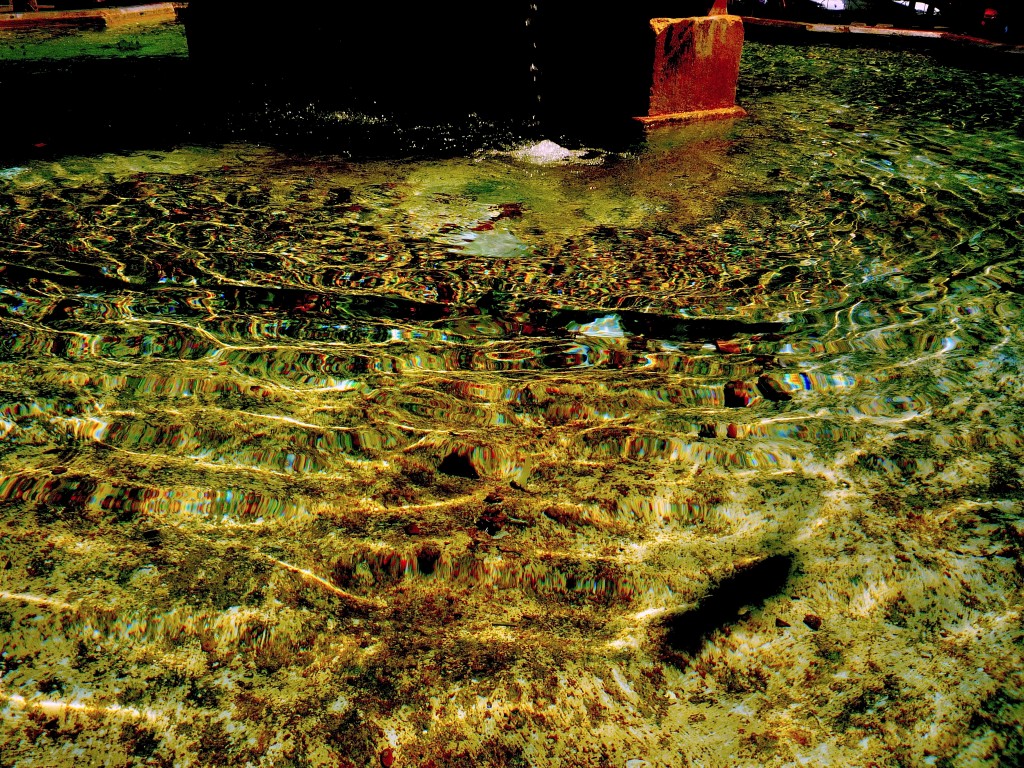

To forearm you for the moment that most good memoirists face, the instant when you honestly cannot tell whether a particular detail, scene, or relationship adds to or distracts from your story arc, let me leave you with my favorite memoir-related image. It requires some set-up: while autobiographies consist of what the author can remember (or, as is common for presidential memoir, what ended up in a journal) of a particular period of time, memoir frequently concentrates upon a single life-changing event or decision — and the effects of that occurrence upon one’s subsequent life and world.

Imagine that event or decision as a stone you have thrown into the pond of your life. Show the reader that stone’s trajectory; describe it and the flinging process in as much loving detail as you like. Make the reader feel as though she had thrown it herself. Then, and only then, will you be in a position to figure out which of the ripples on the pond resulted from shying that rock, and which were caused by the wind.

Keep up the good work!