“A little brains, a little talent — with an emphasis on the latter.”

I was thinking about you the other day, campers, as well as our ongoing series on how to prepare to pitch your book to an agent. While searching fruitlessly for interesting flooring for our mother-in-law apartment (every square foot of previous floor was lost to a tenant’s particularly aggressive cat; believe me, you’ll sleep better tonight if you don’t know the specifics), I stumbled upon one of the worst salespeople it has ever been my hard fate to meet. As a long-time student of human labor both stellar and awful and the people who perform it across a variety of fields, I was, naturally, fascinated.

He wasn’t bad at his job in any of the usual senses: he was not ignorant of the theory or practice of floor covering, nor did he appear to be unconversant with the ways a consumer might conceivably purchase some in an ideal world. His particular gift lay in the direction of implying that he did not care whether I opted to buy Marmoleum from his shop or from another emporium. He managed to convey, not once but perpetually, that while he was an affable guy, he was reaching the end of his rope with all of us darned people bugging him by coming into his store and expecting him to evince some interest in getting our floors covered. If only he were left alone, his every tone and gesture screamed loud and clear, he might just get some work done.

No, you’re not confused. His work did indeed involve selling floor coverings. Or so I surmised, perhaps rashly, from the fact that the shop sold nothing else.

Had he been merely incompetent, I probably would have found him merely annoying or dismissed him as yet another example of the Peter Principle in action. (If you have never read Laurence J. Peter and Raymond Hull’s classic analysis of how hierarchies operate and have ever remotely considered setting a comedy in a workplace, run, don’t walk, to pick up a copy.) There was a touch of genius in just how creative his ineptness was. Clearly, this man worked at being bad at his work.

He didn’t just try to talk me out of considering, say, Tarkett; he generously invested five full minutes in explaining precisely how difficult it would be to order, how unsure he was that the samples he had were representative of what the company had to offer these days, and how only a color-blind idiot would find what he had in stock neither ugly nor uninteresting. (He had a point there.) Then, for the coup de grace, he told a highly unsavory anecdote about how his former Tarkett representative had been summarily fired so, he claimed, her employers would not have to pay her back commissions.

A lesser man might not have shared the actual disputed dollar amount or the gripping details of the subsequent court case, but our fellow was made of sterner stuff — unlike, apparently, any floor covering he could recommend. By the end of his account, he not only had impressed upon me that he didn’t particularly wish to sell any Tarkett on moral grounds; he made me feel that I was a sorry excuse for a human being for ever having considered buying it.

I’m ashamed to say that I would have, too. If only they still made the pattern I liked.

It did not occur to me to question the veracity of this tale of woe and uproar until he was well into a searing indictment of bamboo hardwoods and the madmen who purvey them. His passion for that topic so absorbed him that he barely put any energy at all into brushing off the poor soul on a fool’s errand seeking some carpeting for his daughter’s bedroom.

Midway through his blistering exposé of vinyl laminate and all of its disreputable relatives, I waved a few samples of Marmoleum in front of his face. “Would you think too badly of me,” I inquired meekly, “if I took these home to see how they might look next to the kitchen cabinets?”

He snorted. “If you don’t mind giving business to foreigners.” Then, evidently suspecting that he might have gone a trifle too far, he added, “I do have one of the best installers in the Pacific Northwest for that, though. I think he’s still on work release…”

I thought about his sales technique long after I had written up my own sales slip, forced a deposit upon him, and made my way past the stacks and rolls of flooring that for reasons best known to the Almighty had not yet been snapped up by an eager consumer. “Wow,” I found myself murmuring, “have I ever heard a lot of book pitches like that.”

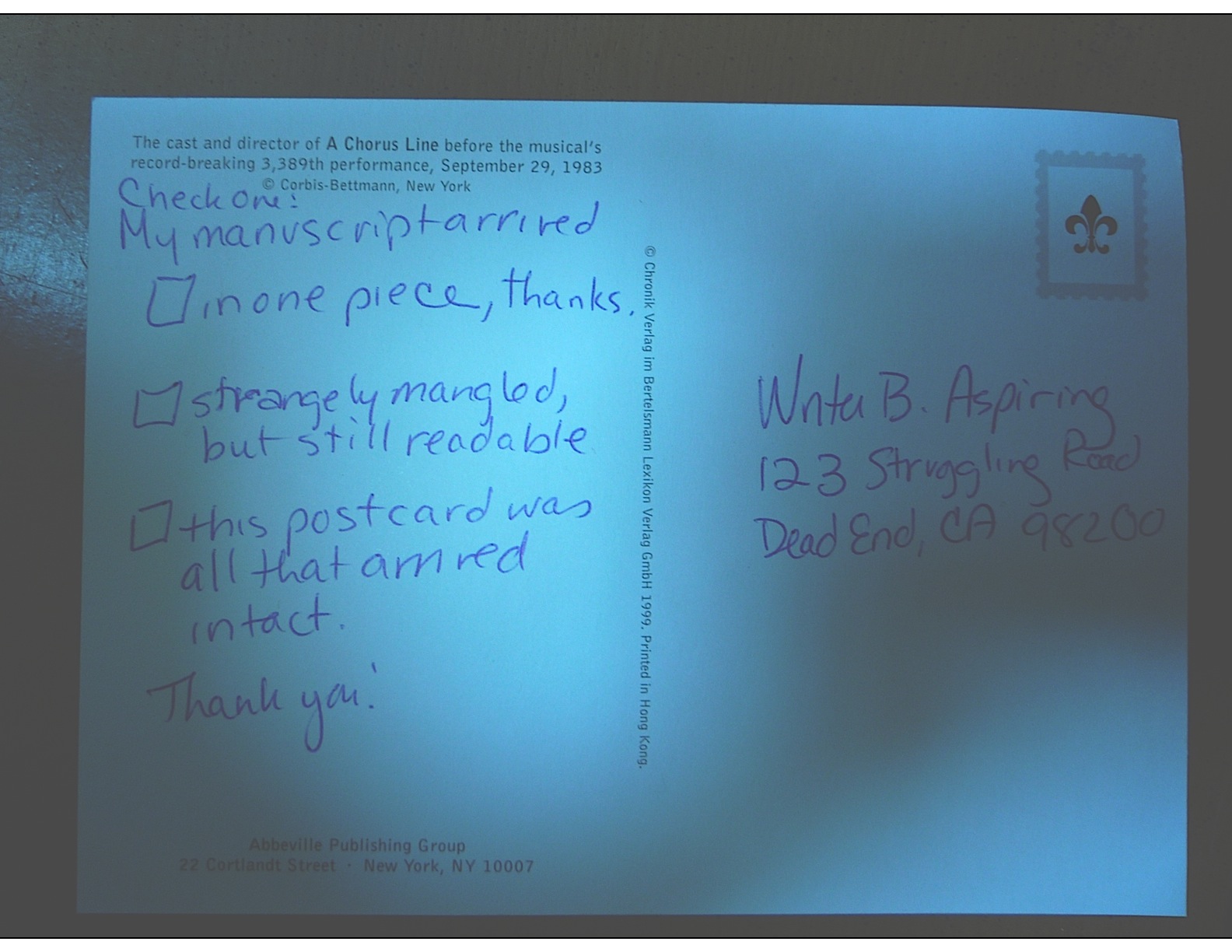

As I mentioned last time, it’s genuinely striking how many aspiring writers pitch as though their goal were to talk an agent or editor out of seriously considering their books. “It’s okay if you don’t want to see pages,” they will assure astonished agents. “It’s already been rejected quite a few times.”

You think I’m making that up, don’t you? Oh, how I wish I were. I also would prefer that this little gem were solely the product of my fevered brain: “My book really isn’t like anything else on the market. I know that agents are only interested in finding the next bestseller.”

Or that I had dreamed hearing this: “What’s my book about? Well, it’s sort of…it’s based on something that really happened. To me. I mean, it’s kind of autobiographical. It’s fiction, though, but I really lived it.”

That last one made some of you do a double-take, didn’t it? “But Anne,” those of you who write thinly-veiled autobiography point out, “that’s not a dissuasive statement. That’s just a statement of fact, isn’t it?”

Not to someone who has heard a lot of pitches, no. Many, if not most, first-time novelists troll their own lives for material; it’s practically a truism that a first novel is as much about the author as about its ostensible subject matter. Yes, even if it is set on the Planet Targ; you thought it wouldn’t be obvious that the three-eyed hydra prone to spitting venom on our blameless heroine was based on the lady who works two cubicles down from you?

As my old friend Philip Dick liked to say: never piss off a living writer. We have ways of making you look bad in perpetuity.

So in wasting even a few seconds in informing an agent that your book is at least semi-autobiographical, you’re probably not telling her something she doesn’t already suspect. (Also, it’s about me and autobiographical mean the same thing; trust me, it’s irritating if you mention both.) Contrary to astoundingly popular opinion amongst aspiring writers, the mere fact that something actually happened does not mean that it will be interesting in print.

As the pros like to say, it all depends on the writing. That means — out comes the broken record again — that your goal in the pitch should be not to convey how much you care about your subject matter or how close you are to it, but to make it sound intriguing enough that the agent or editor in front of you will ask to read some pages.

Leading off with “Well, it’s semi-autobiographical,” is seldom the best way to achieve that. Why? Well, think about it from the point of view of someone who pitches books for a living: because pitches are prone to being cut off in the middle, an agent will generally bring up the book’s prime selling point first.

Is the fact that your novel is based on something that really happened to you honestly the most important thing about it? Is it why you believe a browser in a bookstore would pick it up?

Unless you happen to be a celebrity with national name recognition, probably not. So I ask you: if you had only a single breath to tell that potential reader why to grab your book and peruse the first few pages, as opposed to the one next to it on the shelf, what would you say?

Essentially, you’re in the same position in an informal pitch: what does the agent absolutely need to know about your book?

You should be leading with that information, not assuming that the hearer will glean it from a description of the plot. That’s especially true in an elevator speech: since the average hallway pitcher has only about 30 seconds to make her case, she needs to get to the crux right away.

You have a bit more leeway in a formal pitch meeting, but still, is it in your best interest to talk about the Tarkett saleslady? Wouldn’t you be better served by investing the time in making the Marmoleum sound wonderful?

In order to be able to present your book’s good points successfully, you are going to need to figure out what those good points are. To that end, last time, I suggested that a dandy way to prepare for a conversation with a real, live agent or editor was to sit down and come up with a list of selling points for your book. Or, if you’re pitching nonfiction, how to figure out the highlights of your platform.

Not just vague assertions about why an editor at a publishing house would find it an excellent example of its species of book — that much is assumed, right? — but reasons that an actual real-world book customer might want to pluck that book from a shelf and carry it up to the cash register. It may seem like a pain to generate such a list before you pitch or query, but believe me, it is hundreds of times easier to land an agent for a book if you know why readers will want to buy it.

Trust me, “I spent three years writing it!” is not a reason that is going to fly very well with agents and editors.

Remember, pretty much everyone who approaches them has expended scads of time, energy, and heart’s blood on his book. Contrary to what practically every movie involving a sports competition has implicitly told you, a writer’s wanting to get published more than the next person at a writers’ conference is not going to impress the people making decisions about who does and doesn’t get published.

That means, in practice, that to an agent or editor, the intensity of a writer’s desire to get published is simply irrelevant to a pitch. So are the reasons the writer chose to sit down and write a book in the first place. And, at the risk of engendering howls of protest from those of you accustomed to judging literature by the effort required to produce it, so is how difficult it was to write.

Sad to report, a disproportionately high percentage of pitchers (and quite a few queriers as well) make the serious marketing mistake of giving into the impulse to tell the pitchee about how miserable it was to write this particular book, how discouraging the process was, how hard it was to wrest time for writing from friends, family, job, or volunteering at the local pet rescue. Or, still worse, yielding to the temptation to list how many agents have rejected it, at how many conferences they’ve pitched it, how close a competitor of the person sitting in front of them was to picking it up six months ago, etc.

The more disastrously a pitch meeting is going, the more furiously these pitchers will insist, often with hot tears trembling in their eyes, that this book represents their life’s blood, and so — the implication runs — only the coldest-hearted of monsters would refuse them Their Big Chance. (For some extended examples of this particular species of pitching debacle, please see an earlier post on the subject.) But why would this be important to the hearer? After all, isn’t it only reasonable to assume that pretty much every writer willing to invest substantial time and resources in pitching at a writers’ conference wants to succeed that much?

Sometimes, a pitcher will get so carried away with the passion of describing his suffering that they will forget to pitch the book at all. (Yes, really.) And then he’s astonished when his outburst has precisely the opposite effect of what he intended: rather than sweeping the agent or editor off her feet with his intense love for this manuscript and all he has put himself through to bring it to the attention of an admiring world, all they’ve achieved is to convince the pro that these writers have a heck of a lot to learn about why agents and editors pick up books.

Surprised? Don’t be. A writer who melts down the first time he has to talk about his book in a professional context generally sets off flashing neon lights in an agent’s mind: this client will be a heck of a lot of work. Once that thought is triggered, a pitch would have to be awfully good to wipe out that initial impression of time-consuming hyperemotionalism.

Unfortunately, pitchers who play the emotion card often believe that it’s the best way to make a good impression. Rather than basing their pitch on their books’ legitimate selling points, they fall prey to what I like to call the Great Little League Fantasy: the philosophy so beloved of amateur coaches and those who make movies about them that decrees that all that’s necessary to win in an competitive situation is to believe in oneself.

Or one’s team. Or one’s horse in the Grand National, one’s car in the Big Race, or one’s case before the Supreme Court. You’ve gotta have heart, we’re all urged to believe, miles and miles and miles of heart.

Given the pervasiveness of this dubious philosophy, you can hardly blame pitchers for embracing it. They believe, apparently, that pitching (or querying) is all about demonstrating just how much their hearts are in their work. Yet as charming as that may be (or pathetic, depending upon the number of tears shed during the pitch meeting), this approach typically does not work. In fact, what it generally produces is profound embarrassment in both listener and pitcher.

Which is why, counterintuitively, figuring out who will want to read your book and why is partially about heart: preventing yours from getting broken into seventeen million pieces while trying to find a home for your work.

I’m quite serious about this: I’m trying to get you to think about your work in market terms not merely to help you pitch better, but to pull the pin gently on a grenade that can be pretty devastating to the self-esteem. A lot of writers mistake professional questions about marketability for critique, hearing the fairly straightforward question, “So, why would someone want to read this book?” as “Why on earth would ANYONE want to read YOUR book? It hasn’t a prayer!”

Faced with what they perceive to be scathing criticism, some writers shrink away from agents and editors who ask this perfectly reasonable question — a reluctance to hear professional feedback which, in turn, can very easily lead to an unwillingness to pitch or query ever again.

“They’re all so mean,” such writers say, firmly keeping their work out of the public eye. “It’s just not worth it.”

This response saddens me, because the only book that hasn’t a prayer of being published is the one that is never submitted at all.

There are niche markets for practically every taste, after all. Your job in generating selling points is to show (not tell) that there is indeed a market for your book.

Ooh, that hit some nerves, didn’t it? I can hear some of you, particularly novelists, tapping your feet impatiently. “Um, Anne?” some of you seem to be saying, with a nervous glance at your calendars, “I can understand why this might be a useful document for querying by letter, or for sending along with my submission, but have you forgotten that I will be giving pitches at a conference just a week or so away? Is this really the best time to be spending hours coming up with my book’s selling points?”

My readers are so smart; you always ask the right questions at precisely the right time. So here is a short, short answer: yes.

Before you pitch is exactly when you should devote some serious thought to your book’s selling points; after, it will be too late. Because, you see, if your book has market appeal over and above its writing style (and the vast majority of books do), you should — and I hope by now you’ve anticipated what I’m about to say — make darned sure that your pitch either mentions or demonstrates it.

Not in a general, “Well, I think a lot of readers will like it,” sort of way, but by citing specific, fact-based reasons that they will clamor to read it. Preferably backed by the kind of verifiable statistics we discussed last time.

Why? Because it will make you look professional in the eyes of the agent or editor sitting in front of you — and, I must say it, better than the twenty-five pitchers before you who did not talk about their work in professional terms. Not to mention that dear, pitiful person who wept for the entire ten-minute pitch meeting about how frustrating it was to try to find an agent for a cozy mystery these days.

Thank God she didn’t also make the mistake of buying Tarkett. Then she really would have a reason to weep.

The more solid reasons you can give for believing that your book concept is marketable, the stronger your pitch will be. Think about it: no agent is going to ask to see a manuscript purely because its author says it is well-written, any more than our old pal Millicent the agency screener would respond to a query that mentioned the author’s mother thought the book was the best thing she had ever read with a phone call demanding that the author overnight the whole thing to her.

“Good enough for your mom? Then it’s good enough for me!” is not, alas, a common sentiment in the publishing industry. (But don’t tell Mom; she’ll be so disappointed.)

So let’s get back to constructing that list of selling points for your manuscript, shall we? To recap:

(1) Any experience that makes you an expert on the subject matter of your book.

(2) Any educational credentials you might happen to have, whether they are writing-related or not.

(3) Any honors that might have been bestowed upon you in the course of your long, checkered existence.

(4) Any former publications (paid or unpaid) or public speaking experience.

All of these are legitimate selling points for most books, but try not to get too bogged down in listing the standard prestige items. Naturally, you should include any previous publications and/or writing degrees, but if you have few or no previous publications, awards, and writing degrees to your credit, do not despair. We shall be going through a long list of potential categories in order that everyone will be able to recognize at least a couple of possibilities to add to her personal list.

Let’s get cracking, shall we?

(5) Relevant life experience.

This is well worth including, if it helped fill in some important background for the book. Is your novel about coal miners based upon your twenty years of experience in the coalmining industry? Is your protagonist’s kid sister’s horrifying trauma at a teen beauty pageant based loosely upon your years as Miss Junior Succotash? Mention it.

And if you are writing about firefighting, and you happen to be a firefighter, you need to be explicit about it. It may seem self-evident to you, but remember, the agents and editors to whom you will be pitching will probably not be able to guess whether you have a platform from just looking at you.

There’s a reason that they habitually ask NF writers, “So what’s your platform?” after all.

“Wait just a nit-picking minute, Anne,” those of you who have been paying attention cry. “How precisely is Point #5 different from stammering out in a pitch meeting (or saying in a query letter) that my novel is sort of autobiographical? Wouldn’t an agent or editor translate that as, ‘This book is a memoir with the names changed. Since it is based upon true events, I will be totally unwilling to revise it to your specifications.’”

The distinction I am drawing here is a subtle one, admittedly. Having the background experience to write credibly about a particular situation is a legitimate selling point: in interviews, you will be able to speak at length about the real-life situation.

However, industry professionals simply assume that fiction writers draw upon their own backgrounds for material. But to them, a book that recounts true events in its author’s life is a memoir, not a novel. And, as I mentioned above, contrary to the pervasive movie-of-the-week philosophy, the mere fact that a story is true does not make it more appealing; it merely means potential legal problems.

So how should you handle it? Make the case for the book’s being fascinating first, then demonstrate your credibility by mentioning your credentials afterward.

Either way, that life experience belongs on your list, right?

(6) Associations and affiliations.

If you are writing on a topic that is of interest to some national organization, list it. Also, if you are a member of a group willing to promote (or review) your work, mention it. Some examples:

The Harpo Marx Fan Club has 120, 000 members in the U.S. alone, as well as a monthly newsletter, guaranteeing substantial speaking engagement interest.

Buddy Holly is a well-known graduate of Yale University, which virtually guarantees a mention of her book on tulip cultivation in the alumni newsletter. Currently, the Yale News reaches over 28 million readers bimonthly.

Perhaps it goes without mentioning again, but I pulled all of the examples I am using in this list out of thin air. Probably not the best idea to quote me on any of ’em, therefore.

(7) Trends and recent bestsellers.

If there is a marketing, popular, or research trend that touches on the subject matter of your book, add it to your list. If there has been a recent upsurge in sales of books on your topic, or a television show devoted to it, mention it. (Recent, in industry terms, means within the last five years.)

Even if these trends support a secondary subject in your book, they are still worth including. If you can back your assertion with legitimate numbers (see my earlier posts on the joys of statistics), all the better. Some examples:

Ferret ownership has risen 28% in the last five years, according to the National Rodent-Handlers Association.

Last year’s major bestseller, THAT HORRIBLE GUMBY by Pokey, sold over 97 million copies. It is reasonable to expect that its readers will be anxious to read Gumby’s reply.

(8) Statistics.

At risk of repeating myself, if you are writing about a condition affecting human beings, there are almost certainly statistics available about how many people in the country are affected by it. As we discussed last time, including the real statistics in your pitch minimizes the probability of the agent or editor’s guess being far too low.

Get your information from the most credible sources possible, and cite them. Some examples:

400,000 Americans are diagnosed annually with Inappropriate Giggling Syndrome, creating a large audience potentially eager for this book.

According to a recent study in the Toronto Star, 90% of Canadians have receding hairlines, pointing to an immense potential Canadian market for this book.

(9) Recent press coverage.

I say this lovingly, of course, but people in the publishing industry have a respect for the printed word that borders on the mystical. Minor Greek deities were less revered in 600 B.C. That remains true, even in the midst of the current and ongoing banshee howls over the purportedly imminent demise of same.

Thus, if you can find recent articles related to your topic, you can credibly them as evidence that the public is eager to learn more about it. Possible examples:

So far in 2011 the Chicago Tribune has run 347 articles on mining accidents, pointing to a clear media interest in the safety of mine shafts.

In the last six months, the New York Times has written twelve times about Warren G. Harding; clearly the public is clamoring to hear more about this important president’s love life.

(10) Your book’s relation to current events and future trends.

I hesitate to mention this one, because it’s actually not the current trends that dictate whether a book pitched or queried now will fly off the shelves after it is published: it’s the events that will be happening then.

Current events are inherently tricky as selling points, since it takes a long time for a book to move from proposal to bookstand. Ideally, your pitch to an agent should speak to the trends of at least two years from now, when the book will actually be published.

(In response to that loud unspoken “Whaaa?” I just heard out there: after you land an agent, figure one year for you to revise it to your agent’s specifications and for the agent to market it — a conservative estimate, incidentally — and another year between signing the contract and the book’s actually hitting the shelves. If my memoir had been printed according to its original publication timeline, it would have been the fastest agent-signing to bookshelf progression of which anyone I know had ever heard: 16 months, a positively blistering pace.)

However, if you can make a plausible case for the future importance of your book, go ahead and include it on your list. You can also project a current trend forward. Some examples:

At its current rate of progress through the courts, Christopher Robin’s habeas corpus case will be heard by the Supreme Court in late 2013, guaranteeing substantial press coverage for Pooh’s exposé, OUT OF THE TOY CLOSET.

If tooth decay continues at its current rate, by 2021, no Americans will have any teeth at all. Thus, it follows that a book on denture care should be in ever-increasing demand.

(11) Particular strengths of the book.

You’d be surprised at how well a statement like, BREATHING THROUGH YOUR KNEES is the first novel in publishing history to take on the heartbreak of kneecap dysplasia can work in a pitch or a query letter. If it’s true, that is; if it’s not, and the agent knows it isn’t, few things can get your book rejected faster.

Try to think about how your book could actually improve people’s lives — or speak to their experience. Don’t just assume interest; specify why. (Speaking as someone who has spent the last year having various medical professionals try to wrest her kneecap back into place, I can tell you now that the process’ dramatic appeal isn’t immediately apparent to just anyone.)

So what is your book’s distinguishing characteristic? How is it different and better from other offerings currently available within its book category? How is it different and better than the most recent bestseller on the subject?

One caveat: avoid cutting down other books on the market; try to point out how your book is good and/or useful, not how another book is bad and/or a plague upon humanity.

Why? Well, publishing is a small world: you can never be absolutely sure that the person to whom you are pitching didn’t go to college with the editor of the book on the negative end of the comparison. Or dated the author. Or represented the book himself.

I would strongly urge those of you who write literary fiction to spend a few hours brainstorming on this point. How does your book deal with language differently from anything else currently on the market? How does its dialogue reveal character in a new and startling way? Why might a professor choose to teach it in an English literature class?

Again, remember to stick to the FACTS here, not subjective assessment. It’s perfectly legitimate to say that the writing is very literary, but don’t actually say that the writing is gorgeous.

Even if it undeniably is. That’s the kind of assessment that publishing types tend to trust only if it comes from one of three sources: a well-respected contest (in the form of an award), the reviews of previous publications — and the evidence of their own eyes.

Seriously, this is a notorious pet peeve: almost universally, agents and editors tend to respond badly when a writer actually says that his book is well-written; they want to make up their minds on that point themselves. It tends to provoke a “Show, don’t tell!” response.

In fact, it’s not at all unusual for agents to tell their screeners to assume that anyone who announces in a query letter that this is the best book in the Western literary canon is a bad writer. Next!

Be careful not to sound as if you are boasting. If you can legitimately say, for instance, that your book features the most sensitive characterization of a dyslexic 2-year-old ever seen in a novel, be prepared to back that up with direct comparisons to other books, so it will be heard as a statement of fact, not a value judgment.

Stick to what is genuinely one-of-a-kind about your book — and don’t be afraid to draw direct factual comparisons with other books in the category that have sold well recently. For example:

While Elizabeth Taylor’s current bestseller, EYESHADOW YOUR WAY TO SUCCESS, deals obliquely with the problem of eyelash loss, my book, EYELASH: THE KEY TO A HAPPY, HEALTHY FUTURE, provides much more detailed guidelines on eyelash care.

(12) Any research or interviews you may have done for the book.

If you have done significant research or extensive interviews, list it here. This is especially important if you are writing a nonfiction book, as any background that makes you an expert on your topic is a legitimate part of your platform.

Leonardo DiCaprio has spent the past eighteen years studying the problem of hair mousse failure, rendering him one of the world’s foremost authorities.

Tiger Woods interviewed over 600 married women for his book, HOW TO KEEP THE PERFECT MARRIAGE.

(13) Promotion already in place.

Yes, the kind of resources commonly associated with having a strong platform — name recognition, your own television show, owning a newspaper chain, and the like — will impress agents and editors. You’d be surprised, though how far more modest promotional efforts can go toward suggesting that you are a writer who is savvy about how book marketing actually works.

Having a website already established that lists an author’s bio, a synopsis of the upcoming book, and future speaking engagements, for instance, is helpful in establishing your professional credibility. Frankly, the publishing industry as a whole has been a TRIFLE slow to come alive to the promotional possibilities of the Internet, beyond simply throwing up static websites.

For this reason, almost any web-based marketing plan you may have is going to come across as impressive. Consider having your nephew (or some similarly computer-savvy person who is fond enough of you to work for pizza) put together a site for you, if you don’t already have one.

(14) What makes your take on the subject matter of your book fresh.

This is the time to bring up what makes your work new, exciting, original. If you don’t know what makes your book different and better than what’s already on the shelves, how can you expect an agent or editor to guess?

Actually, I like to see every list of selling points include at least one bullet’s worth of material addressing this point, because it’s awfully important. Again, what we’re looking for here are not merely qualitative assessments (“This is the best book on sailboarding since MOBY DICK!”), but content-filled comparisons (“It’s would be the only book on the market that instructs the reader in the fine art of harpooning from a sailboard.”)

Finished brainstorming your way through all of these points? Terrific. Let’s do something productive with it.

(1) Go through your list and cull the less impressive points. Ideally, you will want to end up with somewhere between 3 and 10, enough to fit comfortably as bullet points on a double-spaced page.

(2) Reduce each point to a single sentence. Yes, this is a pain for those of us who spend our lives meticulously crafting beautiful paragraphs, but trust me, when you are consulting a list in a hurry, shorter is better.

(3) When your list is finished, label it MARKETING POINTS, and keep it by your side until your first book signing. Or when you are practicing answering the question, “So what’s your platform?”

Heck, you might even want to have it handy when you’re giving interviews about your book. Once you’ve come up with a great list of reasons that your book should sell, you’re going to want to bring those reasons up every time you talk about the book, right?

Oh, and keep a copy handy to your writing space. It’s a great pick-me-up for when you start to ask yourself, “Remind me — why I am I putting in all of this work?”

Believe me, in retrospect, you will be glad to have a few of these reasons written down before you meet with — or query — the agent of your dreams. Trust me on this one. And remember me kindly when, down the line, your agent or editor raves about how prepared you were to market your work.

There’s more to being an agent’s dream client than just showing up with a beautifully-written book, you know: there’s arriving with a fully-stocked writer’s toolkit.

Exhausted? I hope not, because for the next couple of weeks, we’re going to be continuing this series at a pretty blistering pace. Next time, I shall move on to constructing those magic few words that will summarize your book in half a breath’s worth of speech. So prepare yourselves to get pithy, everybody.

I’m off to wrestle with flooring decisions. Who knew that they would be so fraught with ethical peril? Keep up the good work!