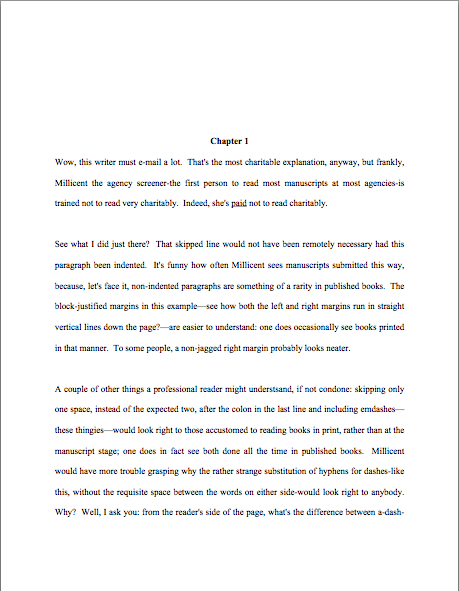

A few weeks ago, while I was deep in the throes of contemplating what subject I should tackle for this, my 1600th post at Author! Author!, a non-writer — or so I surmise, from the bent of her discourse — abruptly flung a rather profound question in my direction. It was, happily for today’s post, one of those questions that would never, ever occur to anyone who had devoted serious time to courting a Muse.

“You’ve been blogging for 7 1/2 years on the same subject?” she gasped, practically indignant with incredulity. “You’ve posted hundreds of times, haven’t you? It’s only writing — what could you possibly still have to say?”

I know, I know: I was sorely tempted to laugh, too. From a writer’s or editor’s perspective, the notion that everything an aspiring writer could possibly need or want to know about the ins and outs of writing and revising a manuscript, let alone how to land an agent, work with a publishing house, promote a book, and/or launch into one’s next writing project, could be covered adequately in a mere 1599 blog posts borders on the absurd. Writing a compelling book constitutes one of the most challenging endeavors life offers to a creative persons mind, heart, and soul; it’s not as though there’s a simple, one-size-fits-all formula for literary success.

At the same time, I could hear in her question an echo of a quite ubiquitous compound misconception about writing. It runs a little something like this: if people are born with certain talents, then good writers are born, not made; if true writers tumble onto this terrestrial sphere already knowing deep down how to write, then all a gifted person needs to do is put pen to paper and let the Muse speak in order to produce a solid piece of writing; since all solid pieces of writing inevitably find a home — an old-fashioned publishing euphemism for being offered a contract by an agent or publishing house — if a writer has been experiencing any difficulty whatsoever getting her book published, she must not be talented. Q.E.D.

With a slight caveat: all of those presumptions are false. Demonstrably so — egregiously so, even. Just ask virtually any author of an overnight bestseller: good books are typically years, or even decades, in the making.

What could I possibly still want to say to writers to help them improve their manuscripts’ chances of success? How long have you got?

We’ve come a long way together, campers: when Author! Author! first took its baby steps back in August, 2005, in its original incarnation as the Resident Writer spot on the nation’s largest writers’ association’s website, little did I — or, I imagine, my earliest readers, some of whom are still loyal commenters, bless ‘em — imagine that I will still be dreaming up post for you all so many years into the future.

Heck, at the outset, I had only envisioned a matter of months. The Organization that Shall Remain Nameless had projected even less: when it first recruited me to churn out advice for aspiring writers everywhere, my brief was to do it a couple of times per week for a month, to see how it went. They didn’t want me to blog, per se — in order to comment, intrepid souls had to e-mail the organization, which then forwarded questions it deemed appropriate to me.

As your contributions flew in and my posts flew up, I have to confess, the Organization that Shall Remain Nameless seemed rather taken aback. Who knew, its president asked, and frequently, that there were so many writers out there longing for some straightforward, practical-minded advice on how to navigate a Byzantine and apparently sometimes arbitrary system? What publishing professional could have sensed the confusion so many first-time writers felt when faced with the welter of advice barked at them online? What do you mean, the guidelines found on the web often directly contradict one another?

And what on earth was the insidious source of this bizarre preference for the advice-giver’s being nice to writers while explaining things to them? It wasn’t as though much of the online advisors actually in the know — as opposed to the vast majority of writing advice that stems from opinion, rumor, and something that somebody may have heard an agent say at a conference somewhere once — were ever huffy, standoffish, or dismissive when they explained what a query letter was, right?

That rolling thunderclap you just heard bouncing off the edges of the universe was, of course, the roars of laughter from every writer who tried to find credible guidance for their writing careers online around about 2006.

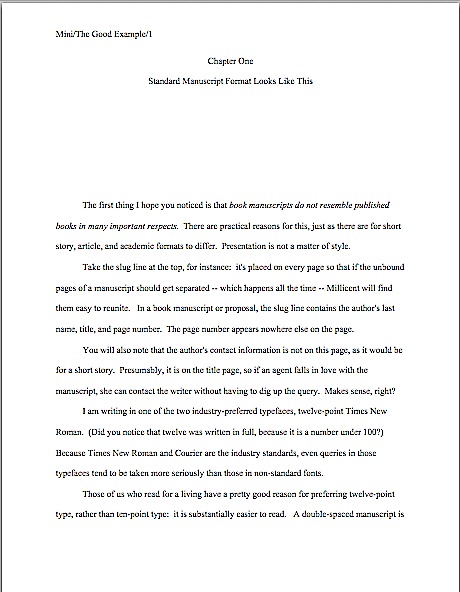

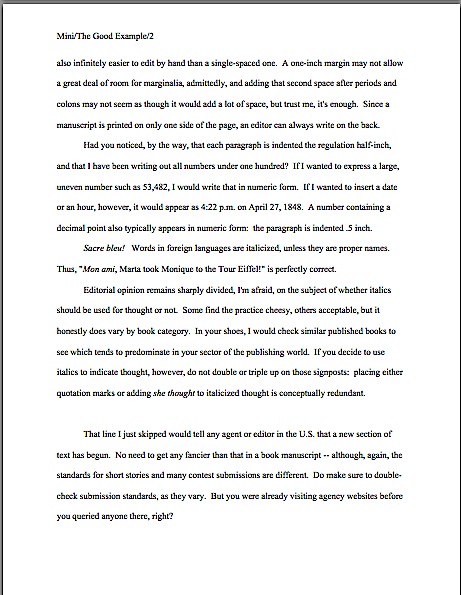

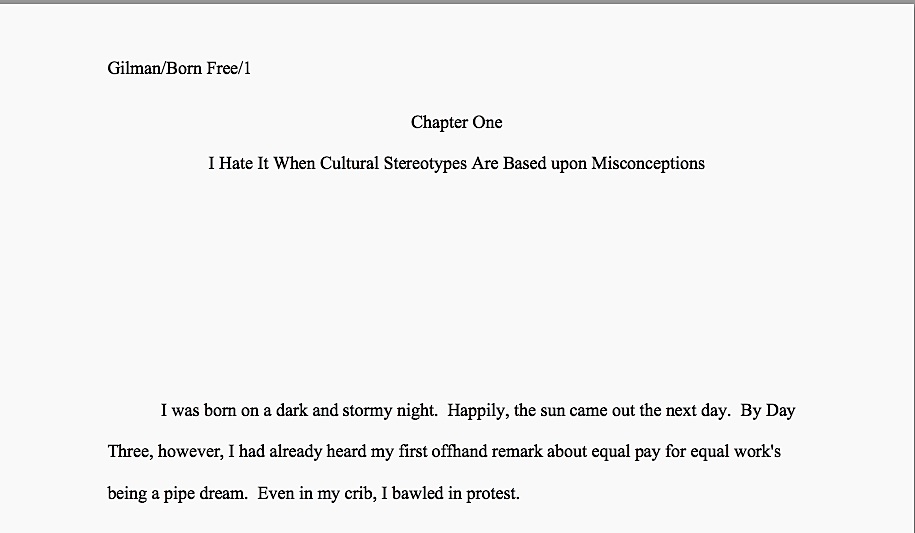

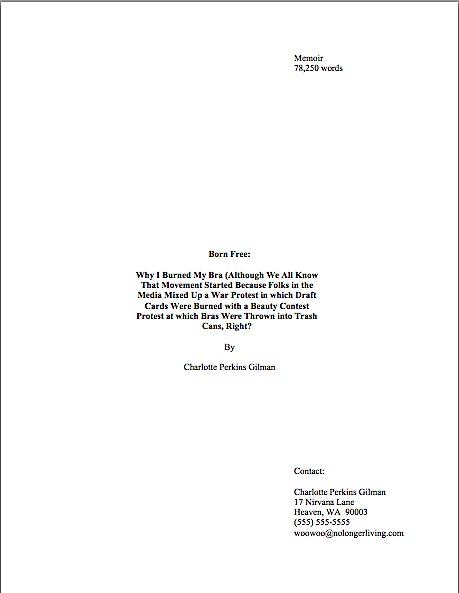

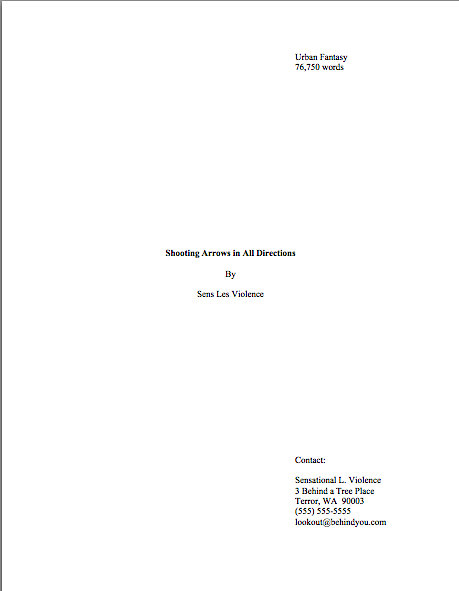

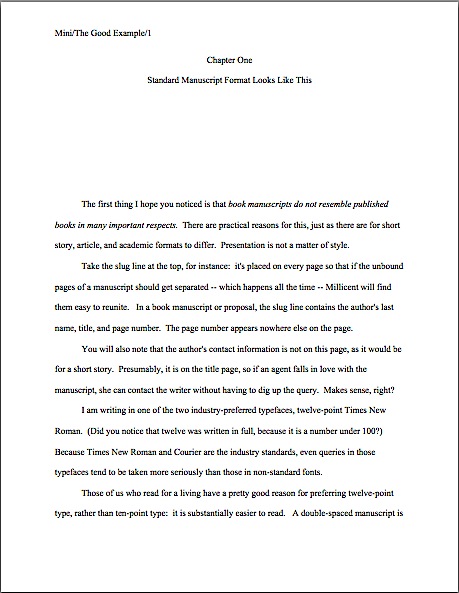

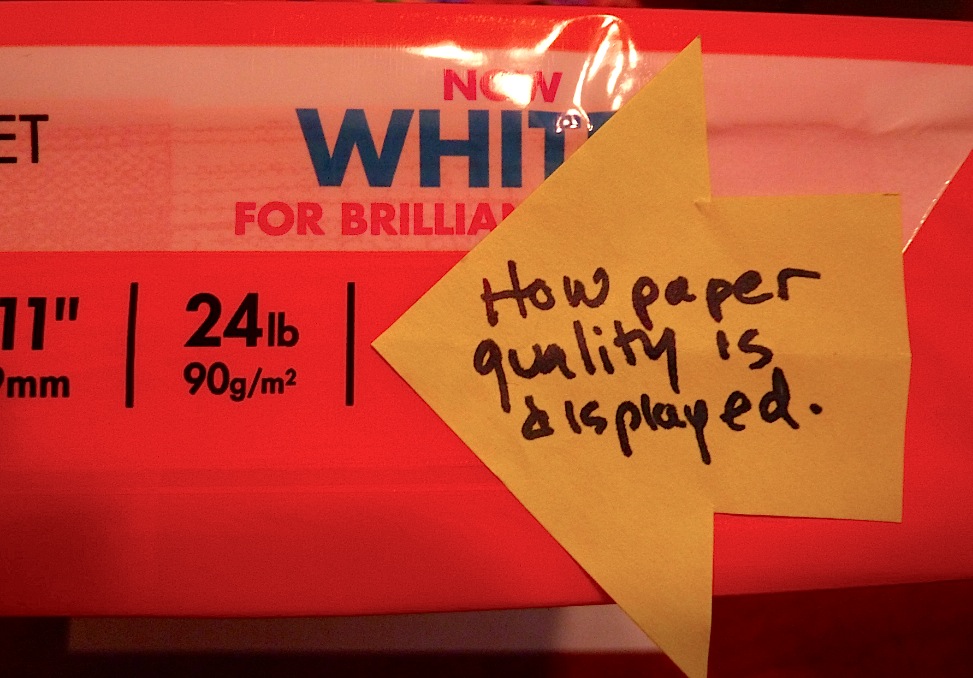

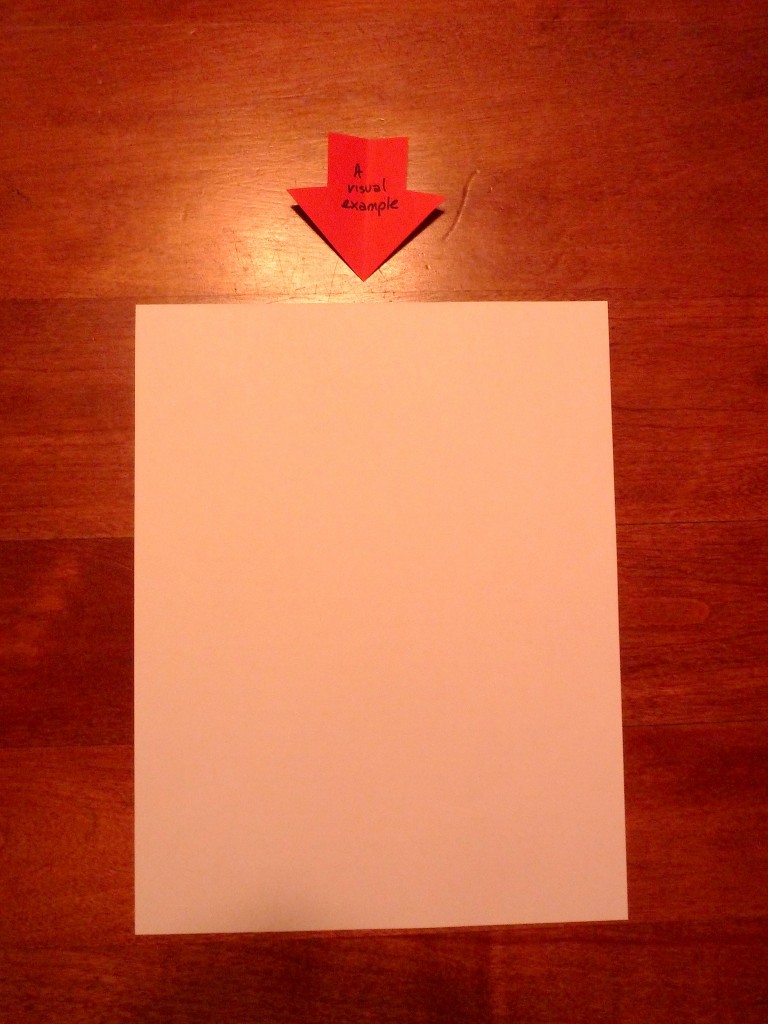

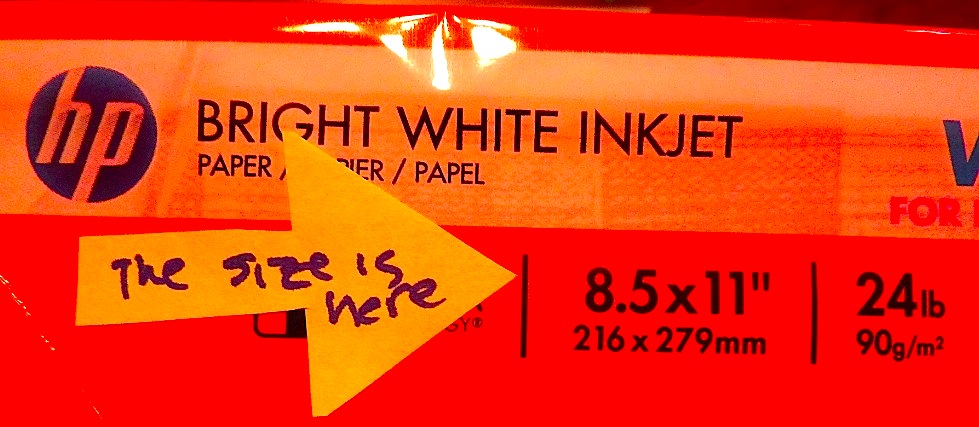

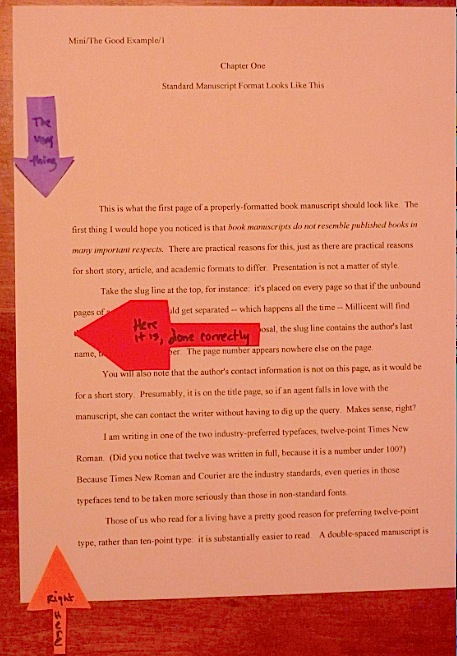

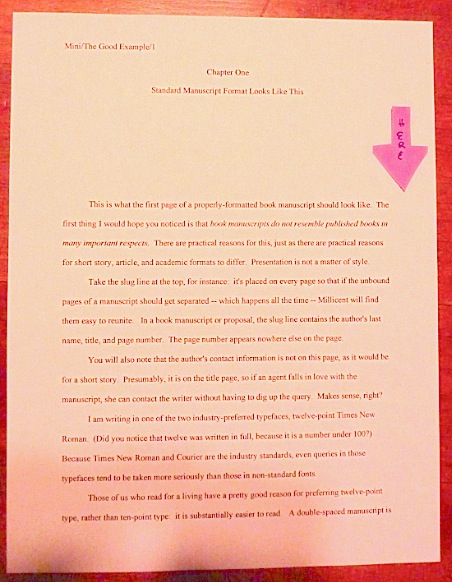

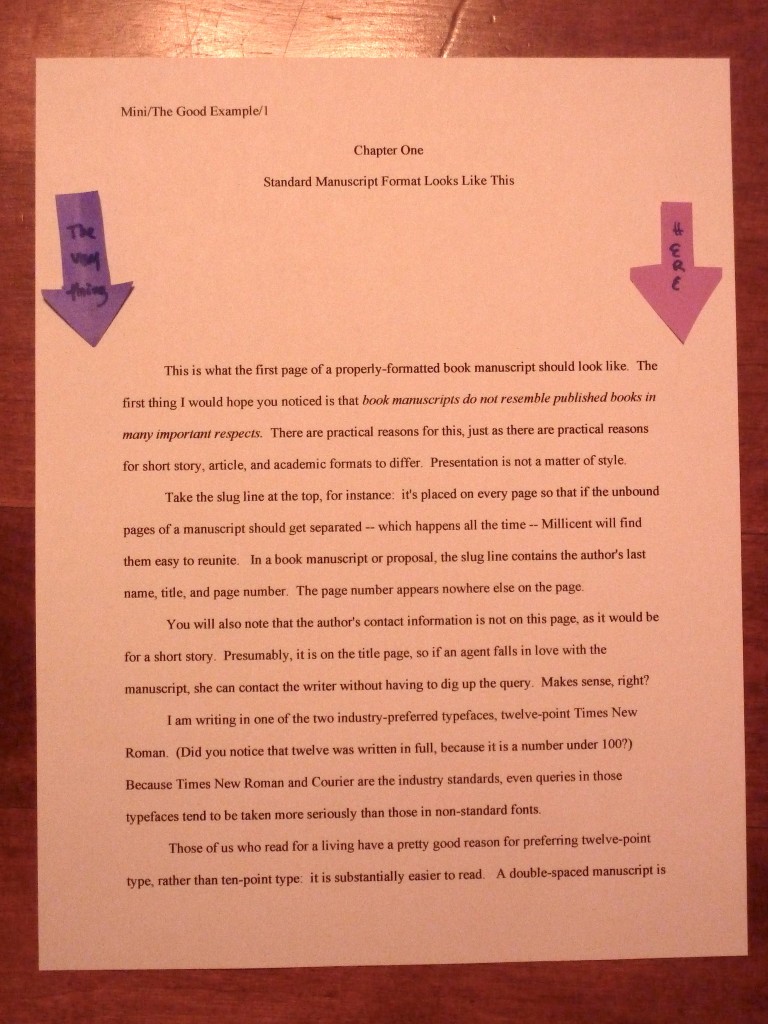

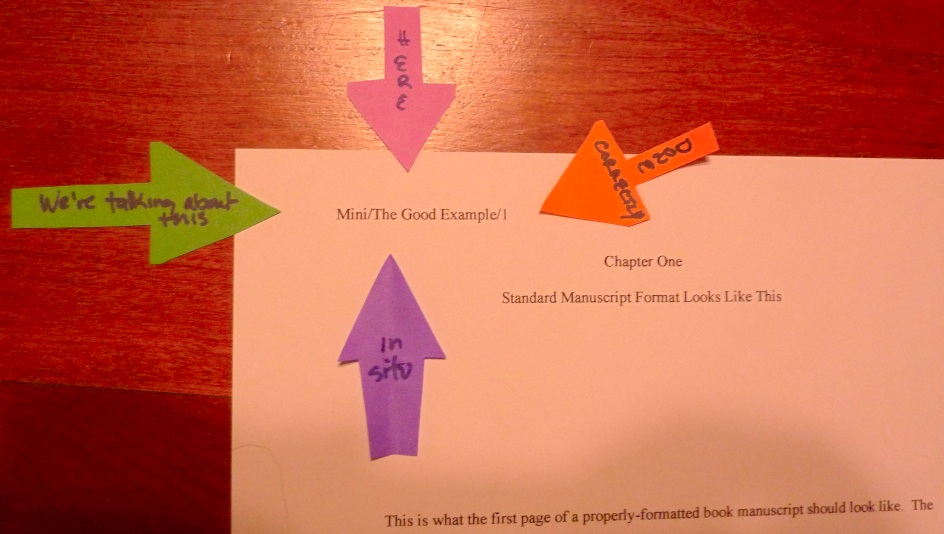

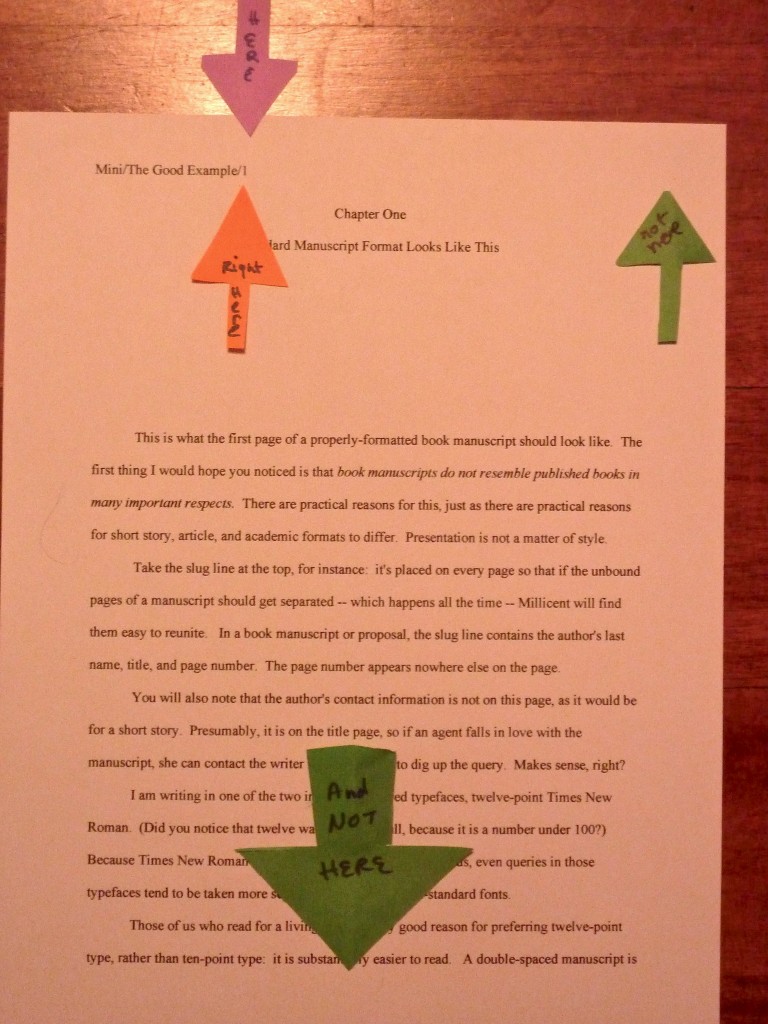

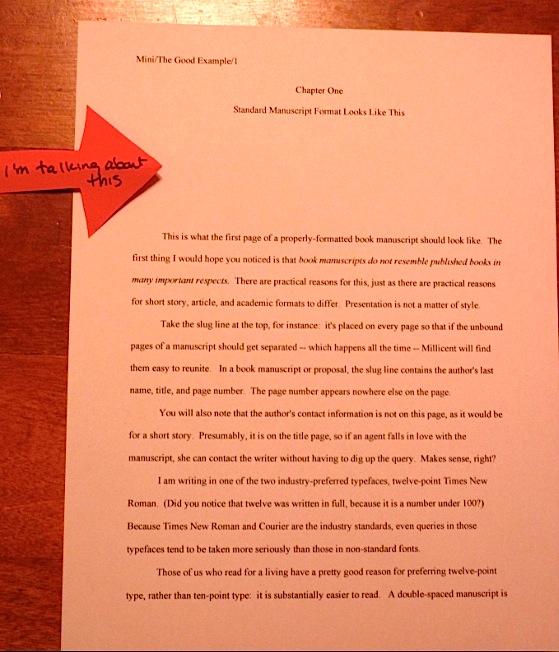

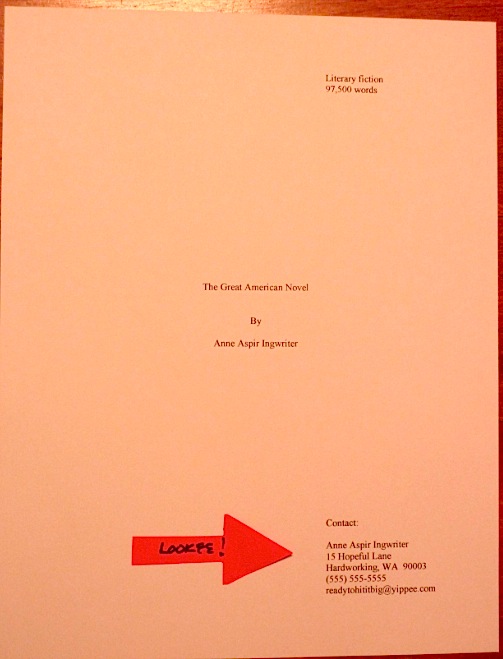

Yet the officers of the Organization that Shall Remain Nameless were not the only ones mystified that there was any audience at all for, say, my posts on how to format a manuscript professionally. Or how to give a pitch. Or how to spot editor-irritating red flags in your own writing. They actually tried to talk me out of blogging about some of these things — because every writer serious about getting published already knows all of that, right?

So why precisely did I think it would be valuable for my readers to be able to see one another’s questions and comments? If I was so interested in building writing community, they suggested, why didn’t I join them in transforming what had arguably been the writers’ association best at helping its members get published into a force to help those already in print find a wider audience? Wouldn’t that be, you know, more upbeat and, well, inspirational than giving all of that pesky and potentially depressing practical advice?

Almost a year and many brisk arguments about respect for writers later, I decided to start my own website. That enabled me to turn Author! Author! into a true blog, a space that welcomed writers struggling and established to share their thoughts, questions, concerns, and, sometimes, their often quite justified irritation at the apparently increasing number of hoops through which good writing — and, consequently, good writers — were being expected to jump prior to publication.

Oh, those of you new to searching for an agent have no idea how tough things were back then. A few of the larger agencies had just started not responding to queries if the answer was no — can you believe it? Some agencies, although far from all, agents had begun accepting e-mailed queries, but naturally, your chances were generally better if your approached them by letter. And I don’t want to shock you, but occasionally, an agent would request a full manuscript, but send a form-letter rejection.

Picture the horror: a book turned down, and the writer had no idea why!

Ah, those days seem so innocent now, do they not? How time flies when you don’t know whether your manuscript is moldering third from the top in a backlogged submission pile, has been rejected without comment, or simply got lost in the mail. Sometimes, it feels as though those much-vaunted hoops have not only gotten smaller, but have been set on fire.

Let’s face it: the always long and generally bumpy road to publication has gotten longer and bumpier in recent years. Not that it was ever true that all that was necessary in order to see your work in print was to write a good book, of course; that’s a pretty myth that has been making folks in publishing circles roll their eyes since approximately fifteen minutes after Gutenberg came rushing out of his workshop, waving a mechanically-printed piece of paper. Timing, what’s currently selling well, what is expected to sell well a couple of years hence, when a book acquired now by a traditional publisher would actual come out, the agent of your dreams’ experience with trying to sell a book similar to yours — all of this, and even just plain, dumb luck, have pretty much always affected what readers found beckoning them from the shelves.

But you’d never know that from most of what people say about how books get published, would you? To hear folks talk, you’d think that the only factor involved was writing talent. Or that agencies and publishing houses were charitable organizations, selflessly devoted to the noble task of bringing the best books written every year to an admiring public.

Because, of course, there is universal agreement about what constitutes good writing, right? And good writing in one genre is identical to good writing for every type of book, isn’t it?

None of that is true, of course — and honestly, no one who works with manuscripts for a living could survive long believing it. The daily heartbreak would be too painful to bear.

But I don’t need to explain that to those of you who have been at this writing gig for a while, do I? I’m sure you recall vividly how you felt the day when you realized that not every good, or even great, manuscript written got published, my friends. Or has that terrible sense of betrayal long since receded into the dim realm of memory? Or, as we discussed over the holidays, does it spring to gory life afresh each time some well-meaning soul who has never put pen to paper asks, “What, you still haven’t published your book? But you’ve been at it for years!”

Now, you could answer those questions literally, I suppose, grimly listing every obstacle even the best manuscript faces on its way to traditional publication. You could, too, explain at length why you have chosen to pursue traditional publishing, if you have, or why you have decided to self-publish, if that’s your route.

I could also have given that flabbergasted lady who asked me why I thought there was anything left to say about writing a stirring speech about the vital importance of craft to fine literature. Or regaled her with horror stories about good memoirs suddenly slapped with gratuitous lawsuits. I could even, I suppose, have launched into a two-hour lecture on common misuses of the semicolon without running out of examples, but honestly, what would have been the point? If wonderful writing conveys the impression of having been the first set of words to travel from a talented author’s fingertips to a keyboard, why dispel that illusion?

Instead of quibbling over whether it’s ever likely — or possible — for a first draft to take the literary world by storm, may I suggest that those of us who write could use our time together more productively? For today, at least, let’s tune out all of the insistent voices telling us that if only we were really talented, our work would already be gracing the shelves of the nearest public library, and settle down into a nice, serious discussion of craft.

Humor me: I’ve been at this more than 7 1/2 years. In the blogging realm, that makes me a great-grandmother.

At the risk of sounding as though I’m 105 — the number of candles on my own great-grandmother’s last cake, incidentally; the women in my family are cookies of great toughness — I’d like to turn our collective attention to a craft problem that seldom gets discussed in these decadent days: how movies and television have caused many manuscripts, fiction and nonfiction both, to introduce their characters in a specific manner.

Do I hear peals of laughter bouncing off the corners of the cosmos again? “Oh, come on, Anne,” readers not old enough to have followed Walter Winchell snicker, “isn’t it a trifle late in the day to be focusing on such a problem? At this juncture, I feel it safe to say that TV and movies are here to stay.”

Ah, but that’s just my point: they are here to stay, and the fact that those forms of storytelling are limited to exploiting only two of the audience’s senses — vision and hearing — for creating their effects has, as we have discussed many times before, prompted generation after generation of novelists and memoirists to create narratives that call upon no other sense. If, at the end of a hard day of reading submissions, an alien from the planet Targ were to appear to our old pal, Millicent the agency screener and ask her how many senses the average Earthling possesses, a good 95% of the pages she had seen recently would prompt her to answer, “Two.”

A swift glance at the human head, however, would prove her wrong. Why, I’ve seen people sporting noses and tongues, in addition to eyes and ears, and I’m not ashamed to say it. If you’re willing to cast those overworked peepers down our subject’s body, you might even catch the hands, skin, muscles, and so forth responding to external stimuli.

So would it really be so outrageous to incorporate some sensations your characters acquire through other sensible organs, as Jane Austen liked to call them? Millicent would be so pleased.

If you’d really like to make her happy — and it would behoove you to consider her felicity: her perception of your writing, after all, is what stands between your manuscript and a reading by the agent or editor of your dreams — how about bucking another trend ushered in by the advent of movies and television? What about introducing a new character’s physical characteristics slowly, over the course of a scene or even several, rather than describing the fresh arrival top to toe the instant he enters the book?

“Sacre bleu!” I hear the overwhelming majority of hopeful novelists and memoirists shouting. “Are you mad? The other characters in the scene — including, if I’m writing in either the first or the tight third person, my protagonist — will first experience that new person visually! Naturally, I must stop the ongoing action dead in its tracks in order to show the reader what s/he looks like. If I didn’t, the reader might — gasp! — form a mental image that’s different from what I’m seeing in my head!”

Why, yes, that’s possible. Indeed, it’s probable. But I ask you: is that necessarily a problem? No narrative describes a character down to the last mitochondrion in his last cell, after all; something is always left to the reader’s imagination.

Which is, if we’re being truthful about it, a reflection of real life, is it not? Rarely, for instance, would an initial glance reveal everything about a character’s looks. Clothes hide a lot, if they’re doing their job, and distance can be quite a concealer. And really, do you count every freckle on the face of each person passing you on the street?

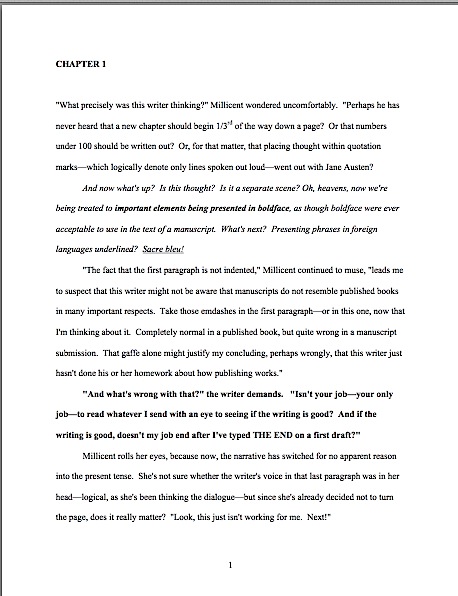

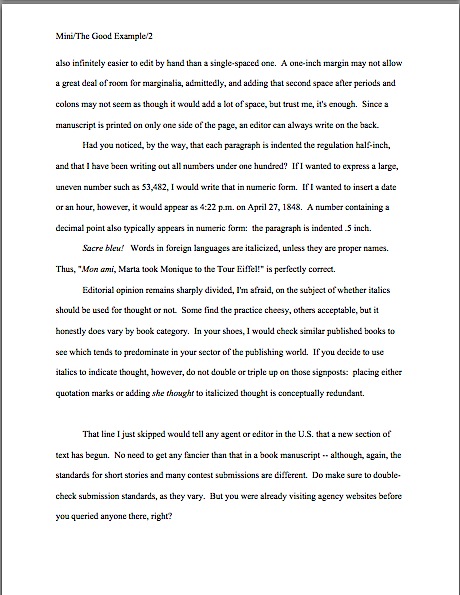

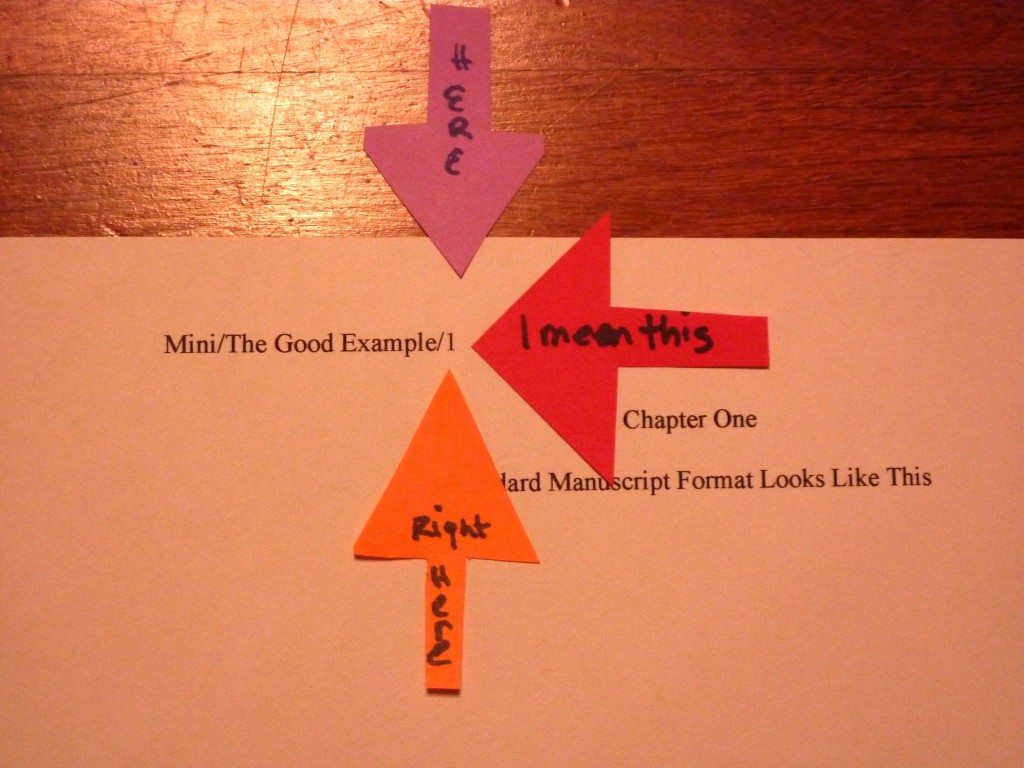

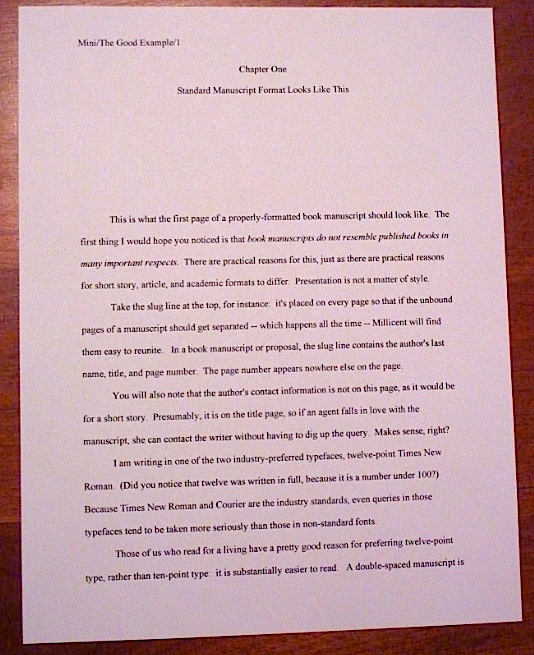

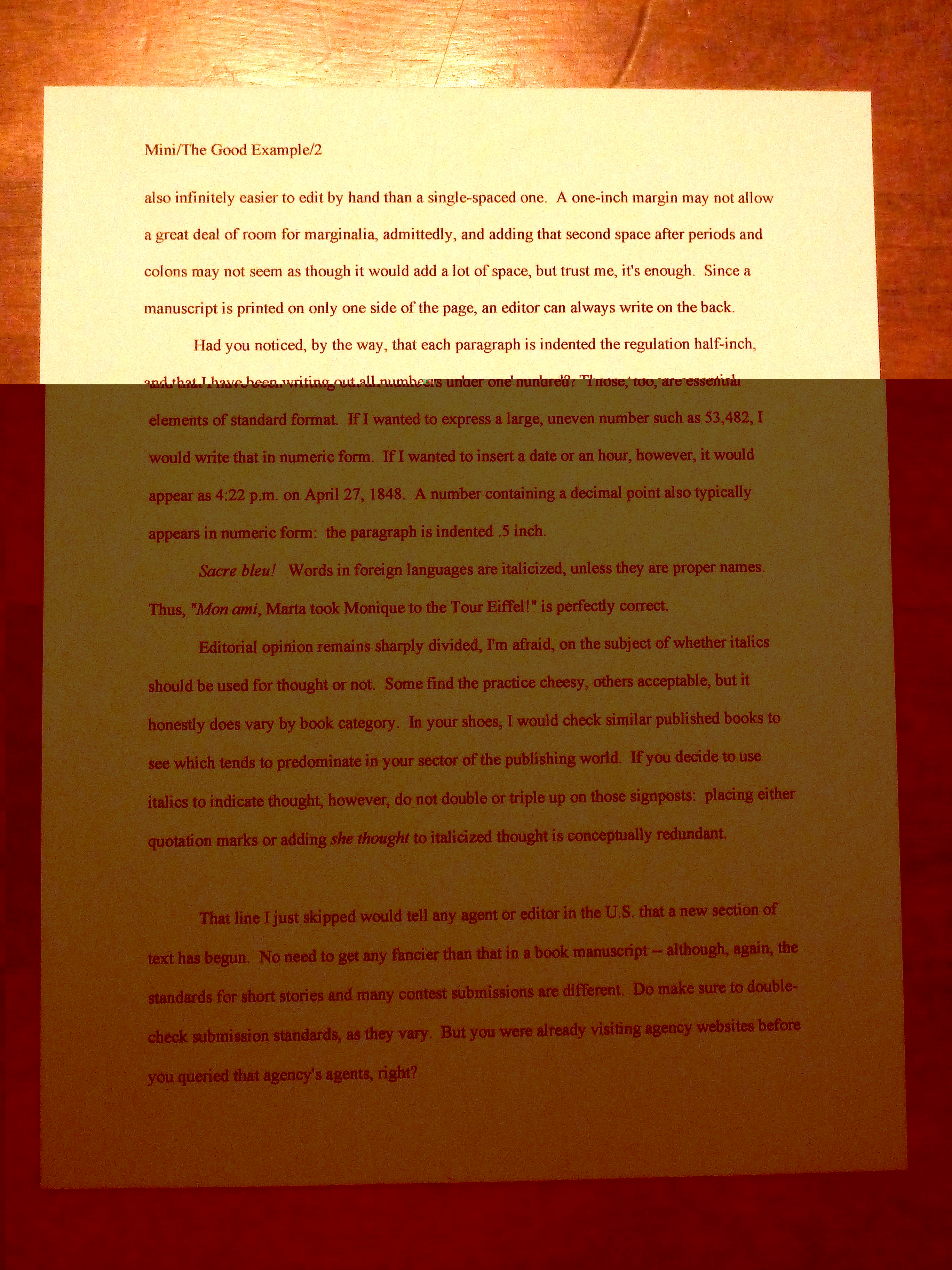

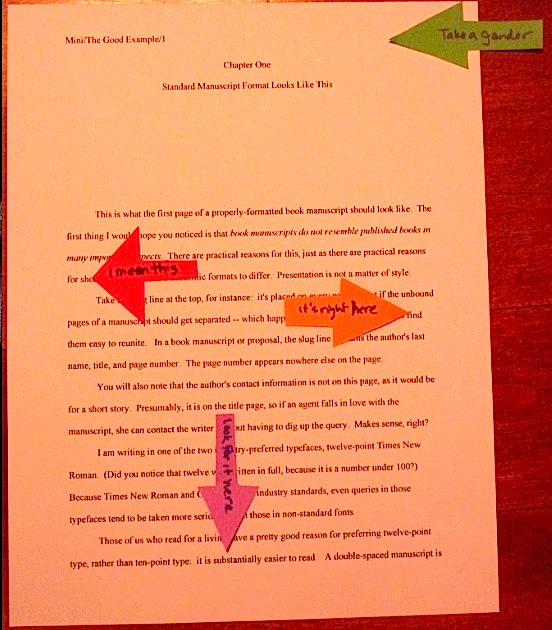

You might be surprised by how many narratives do, especially in the opening pages of a book. Take a gander at how Millicent all too often makes a protagonist’s acquaintance.

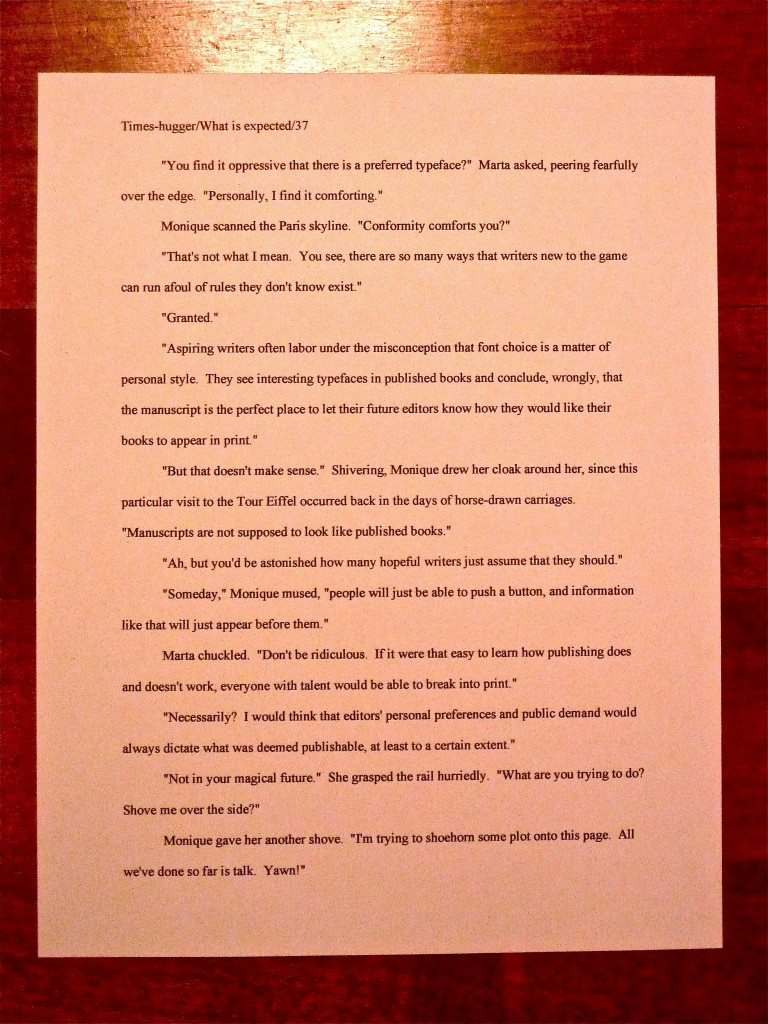

A lean man loped into the distance, shading the horizon with his length even from eighty yards away. Tall as his hero, Abe Lincoln, Jake’s narrow face was hidden by a full beard as red as the hair he had cut himself without a mirror. Calluses deformed his hands, speaking eloquently of years spent yanking on ropes as touch as he was. That those ropes had harnessed the wind for merchant ships was apparent from his bow-legged gait. Pointy of elbow and knee, his body seemed to be moving more slowly than the rest of him as he strode toward the Arbogasts’ encampment.

Henriette eyed him as he approached. His eyes were blue, as washed-out as the baked sky above. Bushy eyebrows punctuated his thoughts. Clearly, those thoughts were deep; how else could she have spotted his anger at twenty paces?

His long nose stretched as he spoke. “Good day, madam,” he said, his dry lips cracking under the strain of speech, “but could I interest you in some life insurance?”

Now, there’s nothing inherently wrong with this description, as descriptions go. Millicent might legitimately wonder if Henriette is secretly Superman, given how sharp her vision seems to be at such great distances (has anybody ever seen Henriette and Superman together?), and it goes on for quite some time, but she might well forgive that: the scene does call for Henriette to watch Jake walking toward her. Millie be less likely to overlook the five uses of as in the first paragraph, admittedly, but you can’t have everything.

Oh, you hadn’t noticed them? Any professional reader undoubtedly would, and for good reason: as is as common in the average submission as…well, anything you’d care to name is anywhere it’s common.

That means — and it’s a perpetual astonishment to those of us who read for a living how seldom aspiring writers seem to think of this — that by definition, over-reliance on as cannot be a matter of individual authorial voice. Voice consists of how an author’s narratives differ from how other writers’ work reads on the page, not in how it’s similar. Nor can it sound just like ordinary people talk, another extremely popular narrative choice. For a new voice to strike Millicent and her boss as original, it must be unique to the author.

The same holds true, by the way, for the ultra-common narrative practice of blurting out everything there is to know about a character visually at his initial appearance: it’s not an original or creative means of slipping the guy into the story. It can’t possibly be, since that tactic has over the past half-century struck a hefty proportion of the writing population as the right or even the only way to bring a new character into a story.

Don’t believe that someone who reads manuscripts all day, every day would quickly tire of how fond writers are of this method. Okay, let’s take a peek at the next few paragraphs of Henriette’s saga.

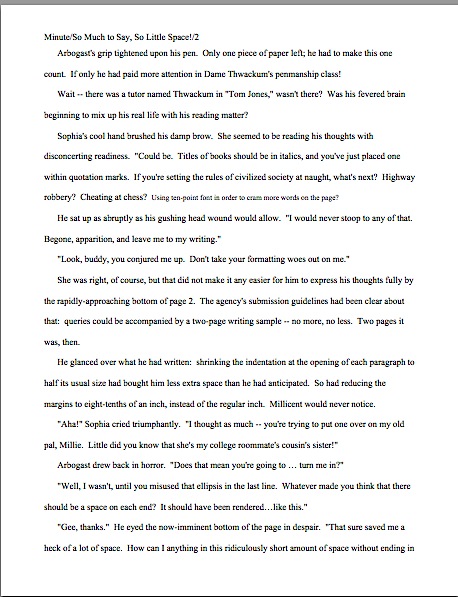

She backed away, her brown suede skirt catching on the nearby sagebrush. She tossed her long, blonde hair out of her face. Her hazel eyes, just the color of the trim on her prim, gray high-necked blouse, so appropriate for the schoolmarm/demolitions expert that she was, snapped as strongly as her voice. A pleasing contralto, when she was not furious, but Jake might never get a chance to hear her sing.

“On your way, mister,” she hissed, adjusting her two-inch leather belt with the fetching iron clasp. Marvin had forged that clasp for her, just before he was carried off by a pack of angry rattlesnakes. She could still envision his tuxedo-clad body rolling above its stripy captors, his black patent leather shoes shining in the harsh midday sun. “We don’t cotton to your kind here.”

An unspecified sound of vague origin came from behind her. She whirled around, scuffing her stylish mid-calf boots. She almost broke one of her lengthy, scarlet-polished fingernails while drawing her gun.

Morris grinned back at her, his tanned, rugged face scrunching into a sea of sun-bleached stubble. His pine-green eyes blinked at the reflection from the full-length mirror Jake had whipped out from under his tattered corduroy coat. It showed her trim backside admirably, or at least as much as was visible under her violet bustle. Her hair — which could be described no other way than as long and blonde — tumbled down her back, confined only by her late mother’s cherished magenta hair ribbon.

Morris caught sight of himself in the mirror. My, he was looking the worse for wear. He wore an open-collared poet’s shirt as red as the previous day’s sunset over a well-cut pant of vermillion velvet. Dust obscured the paisley pattern at the cuff and neck, embroidered by his half-sister, Marguerite, who could be spotted across the street at a second-floor window, playing the cello. Her ebony locks trailed over her bare shoulder as her loosely-cut orange tea gown slipped from its accustomed place.

Had enough yet? Millicent would — and we’re still on page 1. So could you really blame her if she cried over this manuscript, “For heaven’s sake, stop showing me what these people look like and have them do something!”

To which I would like to add my own editorial cri de coeur: would somebody please tell this writer that while clothes may make the man in some real-world contexts, it’s really not all that character-revealing to describe a person’s outfit on the page? Come on, admit it: after a while, Henriette’s story started to read like a clothing catalogue. But since it’s a novel set in 1872, long before any of the characters could reasonably have been expected to watch Project Runway marathons, could we possibly spring for another consonant and let the man wear what most people call them, pants, instead of a pant?

Does that slumped posture and defeated moaning mean that some of you manuscript-revisers are finding seeing these storytelling habits from Millicent’s perspective convincing? “Okay, Anne,” you sigh, “you got me. Swayed by the cultural dominance of visual storytelling, I’ve grown accustomed to describing a face, a body, a hank of hair, etc., as soon as I reveal a character’s existence to the refer. But honestly, I’m not sure how to structure these descriptions differently. Unless you’re suggesting that Henriette should have smelled or tasted each new arrival?”

Well, that would be an interesting approach. It would also, I suspect, be a quite different book, one not aimed at the middle grade reader, if you catch my drift.

Your options are legion, you will be happy to hear: once a writer breaks free of the perceived necessity to run a narrative camera, so to speak, over each character as she traipses onto the page, how to reveal what appearance-related detail becomes a matter of style. And that, my friends, should be as original as your voice.

If my goal in blogging were merely to be inspirational, as Author! Author!’s original hosts had hoped, that would have been a dandy place to end the post, wouldn’t it? That last paragraph, while undoubtedly possessed of some sterling writing truths, did not cough up much actual guidance. And you fine people, I know from long experience, come to this site for practical advice, illustrated by examples.

For insight into how breaking up a physical description for a new character can knock the style ball out of the proverbial park, I can do no better than to direct your attention to that much-copied miracle of authorial originality, Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. To render this example even more frantically literary, I have transcribed these excerpts from the 1908 F.F. Collier and Son edition (W. Blaydes, translator) Philip K. Dick gave me for my eleventh birthday.

Why that particular edition, for a reader so young? Because the Colliers had the foresight to corral another novelist in whose work Philip had been trying to interest me, into writing the introduction. Henry James was considered a real up-and-comer at the turn of the twentieth century.

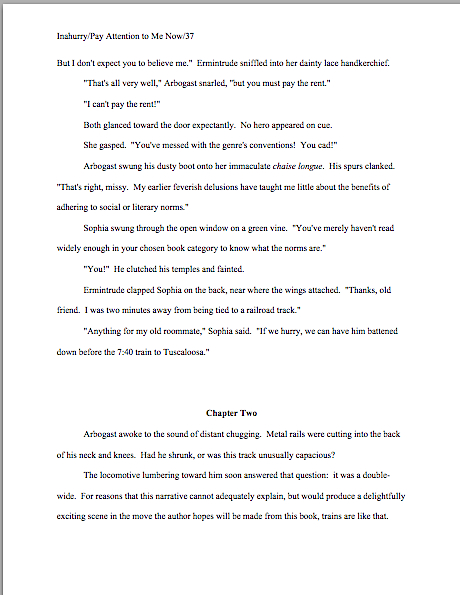

Feeling sufficiently highbrow? Excellent. Here’s the reader’s first glimpse of the immortal Emma Bovary:

A young woman, clad in a dress of blue merino trimmed with three flounces, came to the threshold of the house to receive M. Bovary, whom she introduced into the kitchen where there blazed a big fire. The breakfast of the household was ready prepared and boiling hot, in little pots of unequal size, distributed about. Damp clothes were drying within the chimney-place…

That’s it. Rather sparse as physical descriptions go, isn’t it, considering that this novel’s account of this woman’s passions is arguably one of the most acclaimed in Western literature? Yet at this moment, set amongst the various objects and activities in M. Roulaut’s household, she almost seems to get lost among the furniture.

Ah, but just look at the next time she appears. Charles, the hero of the book so far, now begins to notice her, but not entirely positively.

To provide splints, someone went to fetch a bundle of laths from under the carts. Charles selected one of them, cut it in pieces and polished it with a splinter of glass, while the servant tore up sheets to make bandages and Mlle. Emma tried to sew the necessary bolsters. As she was a long time finding her needle-case, her father grew impatient; she made no reply to him, but, as she sewed, she pricked her fingers, which she then raised to her mouth and sucked.

That’s a nice hunk of character development, isn’t it? Very space-efficient, too: in those few lines, we learn her first name, that she’s not very good at sewing, and that she’s not especially well-organized, as well as quite a lot about her relationship with her father. Could a minute description of her face, figure, and petticoat have accomplished as much so quickly?

But wait: there’s more. Watch how the extreme specificity of Flaubert’s choice of an ostensibly practically-employed body part draws Charles’ sudden observation. At this point in the novel, he and Emma have known each other for two pages.

Charles was surprised by the whiteness of her nails. They were bright, fine at the tips, ore polished than the ivories of Dieppe, and cut almond-shape. Her hand, however, was not beautiful: hardly, perhaps, pale enough, and rather lean about the finger joints; it was too long, also, and without soft inflections of line in the contours.

His being so critical of her caught you off guard, did it not? The paragraph continues:

A feature really beautiful in her was her eyes; although they were brown, they seemed black by reason of their lashes, and her glance came to you frankly with a candid assurance.

This passage reveals as much about Charles as about Emma, I think: how brilliant to show the reader only what happens to catch this rather limited man’s notice. Because his observation has so far been almost entirely limited to the physical, it isn’t until half a page later that the reader gains any sense that he’s ever heard her speak. Even then, the reader only gets to hear Charles’ vague summaries of what she says, rather than seeing her choice of words.

The conversation at first turned on the sick man, then on the weather, the extreme cold, the wolves that scoured the fields at night. Mlle. Rouault did not find a country life very amusing, now especially that the care of the farm devolved almost entirely on herself alone. As the room was chilly, she shivered as she ate, and the shivering caused her full lips, which in her moments of silence she had a habit of biting, to part slightly.

Didn’t take Charles — or the narrative — long to slip back to the external, did it? Now, and only now, is the reader allowed the kind of unfettered, close-up look at her that Millicent so often finds beginning in the first sentence in the book that mentions the character.

Her neck issued from a white turned-down collar. Her hair, so smooth and glossy that each of the two black fillets in which it was arranged seemed a single solid mass, was divided by a fine parting in the middle, which rose or sank slightly as it followed the curve of her skull; and, covering all but the lobe of the ears, it was gathered behind into a large chignon, with a waved spring towards the temples, which the country doctor now observed for the first time in his life. Her cheeks were pink over the bones. She carried, passed in masculine style between two buttons of her bodice, eye-glasses of tortoise-shell.

Quite a sensuous means of tipping the reader off that she’s a fellow reader, isn’t it? Two paragraphs later, we hear her speak for the first time:

“Are you looking for something?” she asked.

The initial words a major character speaks in a story, I’ve found, are often key to developing character on the page. Choose them carefully: in a third-person narrative, it’s the first time that this person can speak for herself. Make them count.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not urging any of you to copy Flaubert. His narrative voice would be pretty hard to sell in the current literary market, for one thing — did you catch all of those which clauses that would have been edited out today? — and, frankly, his work has been so well-loved for so long that a novel that aped his word use would instantly strike most Millicents as derivative. As some wise person once said, a strong authorial voice is unique.

Oh, wait, that was me, and it was just a few minutes ago. How time flies when we’re talking craft.

I hear those gusty sighs out there, and you’re quite right: developing an individual voice and polishing your style can be time-consuming. It took Flaubert five years to write Madame Bovary.

Take that, naysayers who cling to the notion that the only true measure of talent is whether a first draft is publishable. The Muses love the writer willing to roll up her sleeves, take a long, hard look at her own work, and invest some serious effort in making sure that all of that glorious inspiration shows up on the page.

So what, in the end, did I say to the lady who exclaimed over the notion that I could possibly have spent more than seven years writing about writing? Oh, I treated to her the usual explanation of how tastes change, trends waver, and the demands of professional writing differ from year to year, if not day to day. If the expression in her stark blue eyes was any indication, she lost interest midway through my third sentence.

The true answer, however, came to me later: in all of these years, and in 1599 posts, I had never shared my favorite depiction of falling in love with you charming people. A shallow love, to be sure, but a memorable description. And for the prompt to whip out this volume, I owe that lady some thanks.

Do I have more to say about writing? Just try to stop me. Keep up the good work!