Hint: not like this

I’m going to try something a little different today, campers. This post is for all of you strong, silent types: instead of explaining at my usual great length how to put together a manuscript for submission to the agent of your dreams, I’m going to show you.

What brought on this change in tactic? Well, last time, I gave those of you that had just pitched your work successfully to an agent — which, contrary to astoundingly pervasive opinion amongst conference-goers, means that the agent asked to see all or part of your manuscript or book proposal, not offered on the spot to represent you — a brief overview of what that agent would expect to see in a submission. I did that not only to aid writers in a whirl about how to get their work out the door, but also to provide advance knowledge to those of you planning upon pitching at a writers’ conference in the months to come and those of you planning to send out queries. In fact, I shall be devoting the rest of the week to this worthy endeavor.

Why devote so much energy to talking about something as seemingly simply straightforward as packing up a manuscript and sending it to someone that has asked to see it? Because knowing what’s expected can both streamline the submission process and render the preparation stage substantially less stressful. Because there’s more to it than meets the eye. And, frankly, because most submitters do some part of it wrong.

How? Oh, in a broad array of ways. Some manuscripts are formatted as if they were published books. Others are mostly correct, but do not apply the rules consistently or present the text in a wacky font. Still others cherry-pick which rules to follow, or combine the rules for short stories and those for book-length works into an unholy mish-mash of styles.

And those are just the manuscripts put together by writers that are aware that some standards for professional presentation exist. Agents see plenty of submissions from those that evidently believe that everything from margin width to typeface is purely an expression of individual style.

Back in the decadent days when being asked to submit a manuscript meant, if not an offer of representation, then at least an explanation of why the agent was passing on the project, rejected writers were often firmly but kindly told to learn the ropes before submitting again. And today, many agencies have been considerate enough to post some indication of their formatting requirements on their websites. But more often than not, submitters whose manuscripts deviated from expectations never find out that unprofessional presentation played any role at all in their rejection.

So how are they to learn how to improve their writing’s chances of pleasing the pros?

This evening, I’m going to be concentrating on the cosmetic expectations for a manuscript. But before my long-term readers roll their eyes — yes, yes, I know, I do talk about standard format quite a bit — let me hasten to add that in this post, I am going to present manuscript pages in a different manner than I ever have before.

You see, I’ve been talking about standard format for manuscripts for almost seven years now at Author! Author!, long enough to notice some trends. First trend: this is one of the few writer-oriented online sources for in-depth explanations of how and why professional manuscripts are formatted in a very specific manner — and are formatted differently than short stories, magazine articles, or published books. As the sharper-eyed among you may have gleaned from the fact that I devote several weeks of every year to discussing standard format and providing visual examples (the latest rendition begins here), I take that responsibility very seriously.

Which is why the second trend troubles me a little: whenever a sponsor a writing contest — and I am offering two this summer, one aimed at adult writers writing for the adult market and a second for writers under voting age and adult YA writers — a good two-thirds of the entries are improperly formatted. Not just in one or two minor respects, either. I’m talking about infractions serious enough that, even if they would not necessarily prompt our old pal, Millicent the agency screener, to reject those pages on the spot, they would at least encourage her to take the writing less seriously.

Why might someone that reads submissions for a living respond that drastically? Chant it with me now, long-time readers: because all professional book-length manuscripts handled by US-based agencies and publishing houses look essentially the same, writing presented in any other manner distracts Millicent. So if you want your work to claim her full attention, it’s very much to your advantage to present it as the pros do.

I could encourage you to embrace this excellent strategy in a number of ways. I could, for instance, keep inventing reasons to shoehorn the link to the rules for standard format for book manuscripts. I could also make adhering to the strictures of standard format a requirement for entering a writing contest, and then construct a post in which I list the rules one by one, showing how incorporating each would change how a manuscript aimed at an adult audience appeared on the page. I could even, I suppose, take a theoretical entry to a young writers’ contest, apply the rules to it, and post the results.

All of that would be helpful, I suspect, to the many, many aspiring writers who have never seen a professionally-formatted manuscript in person. Yet I must confess, I worry about writers that learn more easily from visual examples than extensive explanation. Not to mention those that are in just too much of a hurry to read through post after post of careful demonstration of the rules in practice.

Today, then, I am going to present standard format for book manuscripts in the quickest, visually clearest way that I can: I’m going to draw you a map.

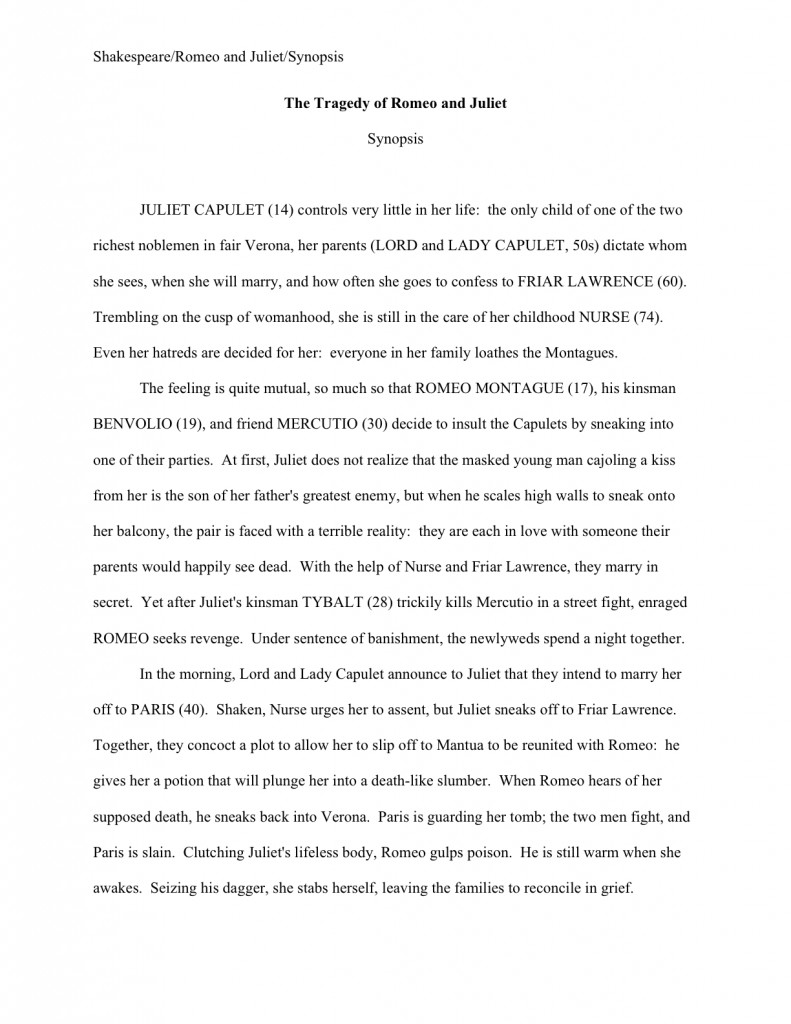

Or, to be a trifle more precise about it, this post will provide a guide to the professional manuscript page that will allow those new to it to navigate around it with ease. Let’s start by taking a peek at the first three pages an agent would expect to see in a manuscript, as the agent would expect to see it: the title page, page 1, and page 2.

Pretty innocuous presentation, isn’t it? (If you’re experiencing difficulty seeing the details, try holding down the COMMAND key and pressing + repeatedly to enlarge the images.) As we may see, book manuscripts differ from published books in many important respects. Some respects that might not be obvious above:

Book manuscripts should be typed or printed in black ink on 20-lb or heavier white paper.

I encourage my clients to use bright white 24-lb paper; it doesn’t wilt.

Manuscripts are printed or typed on one side of the page and are unbound in any way.

The preferred typefaces for manuscripts are 12-point Times New Roman or Courier.

No matter how cool your desired typeface looks, or how great the title page looks with 14-point type, keep the entire manuscript in the same font and typeface.

Due to the limitations of blog format, you’re just going to have to take my word for it that all of these things were true of the manuscript pages I am about to show you. I printed them out and labeled their constituent parts, so we could talk about them more easily. Then I slapped the result onto the nearest table, and snapped some glamour shots. The lighting could have been better, but here they are, in all their glory.

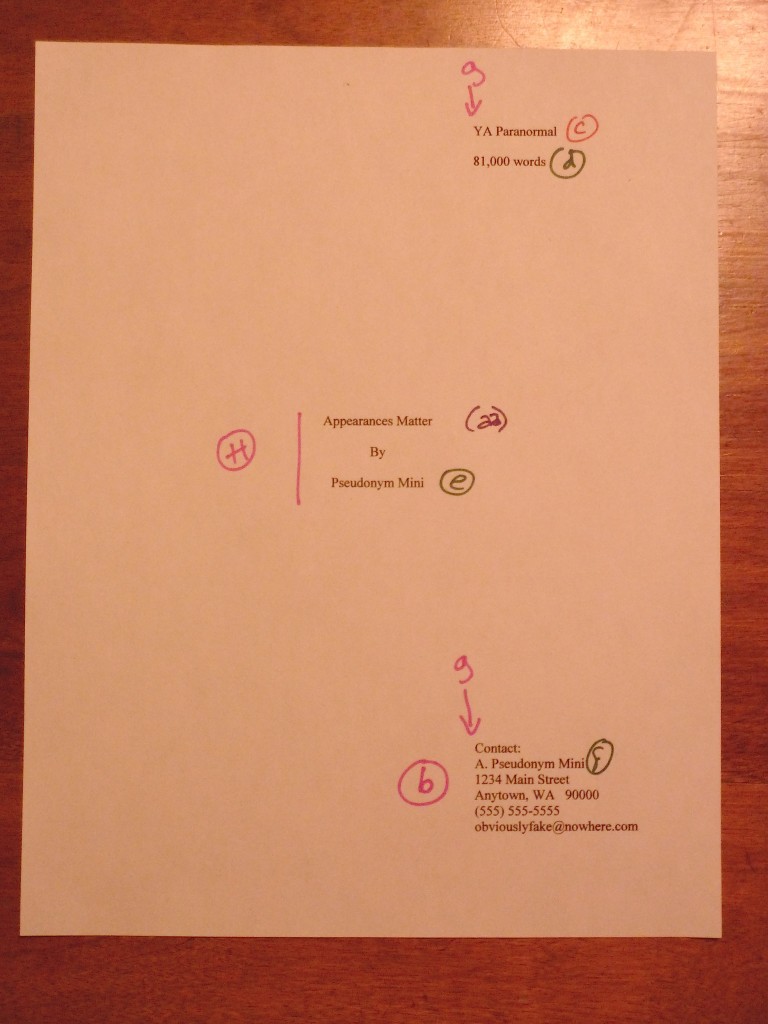

I’ll go into the reasoning behind including a title page in a submission (it’s a good idea, even if you’ve been asked to send only the first few pages) in tomorrow’s post, so for now, let’s just note what information it contains and where it appears on the page. A professionally-formatted title page presents:

A professionally-formatted title page should include all of the following: the manuscript’s book category (c), word count (d), author’s intended publication name (e), author’s real name (f), and author’s contact information (b).

Don’t worry; I shall be defining all of these terms in my next post.

The title and author’s pen name should be centered on the page. (h)

The book category, word count, and contact information should all be lined up vertically on the page. (g)

The easiest way to pull this off is to set a tab at 4″ or 4.5″.

Do not use boldface anywhere in the manuscript but on the title page — and even there, it’s optional.

As you may see here, I have elected not to use it. If I did, the only place where it would be appropriate is at (aa), the title.

Contact information for the author belongs on the title page, not page 1. (b)

Which is, of course, a nicety that would escape the notice of a submitter that believed that short story format (in which the word count and contact information are presented on page 1) and book manuscript format were identical. By including a title page, you relieve yourself of the necessity to cram all of that information onto the first page of a chapter. As you may see, the result is visually much less cluttered.

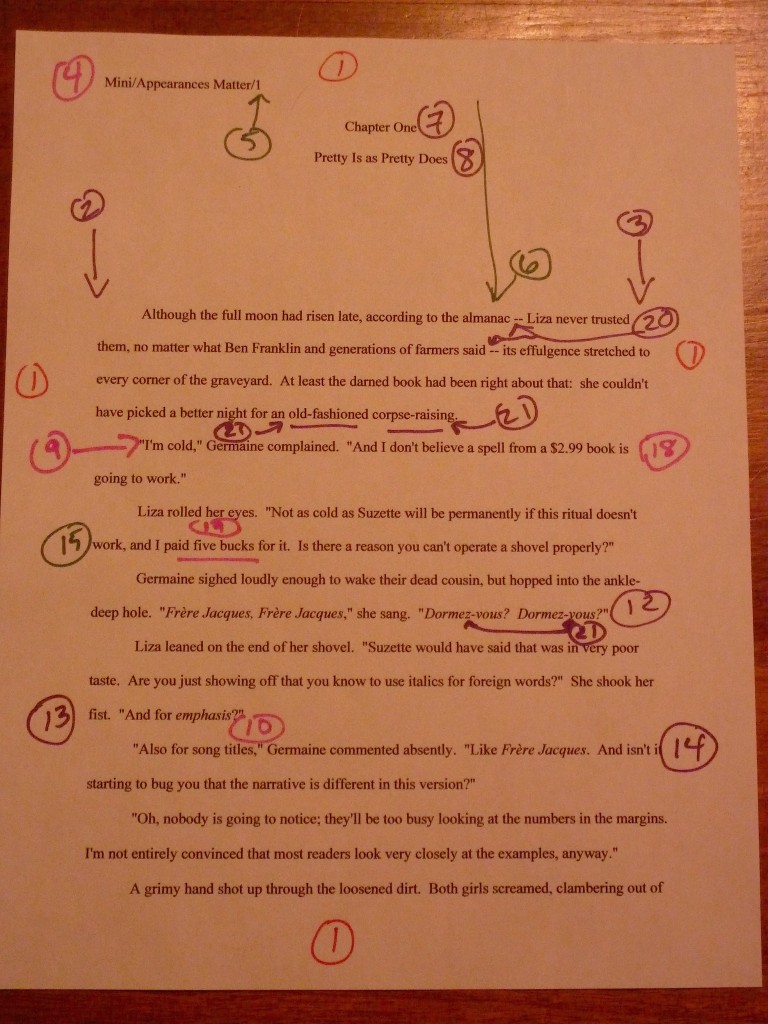

Every page in the manuscript should be numbered except the title page. The first page of text is page 1. (5)

In other words, do not include the title page in a page count.

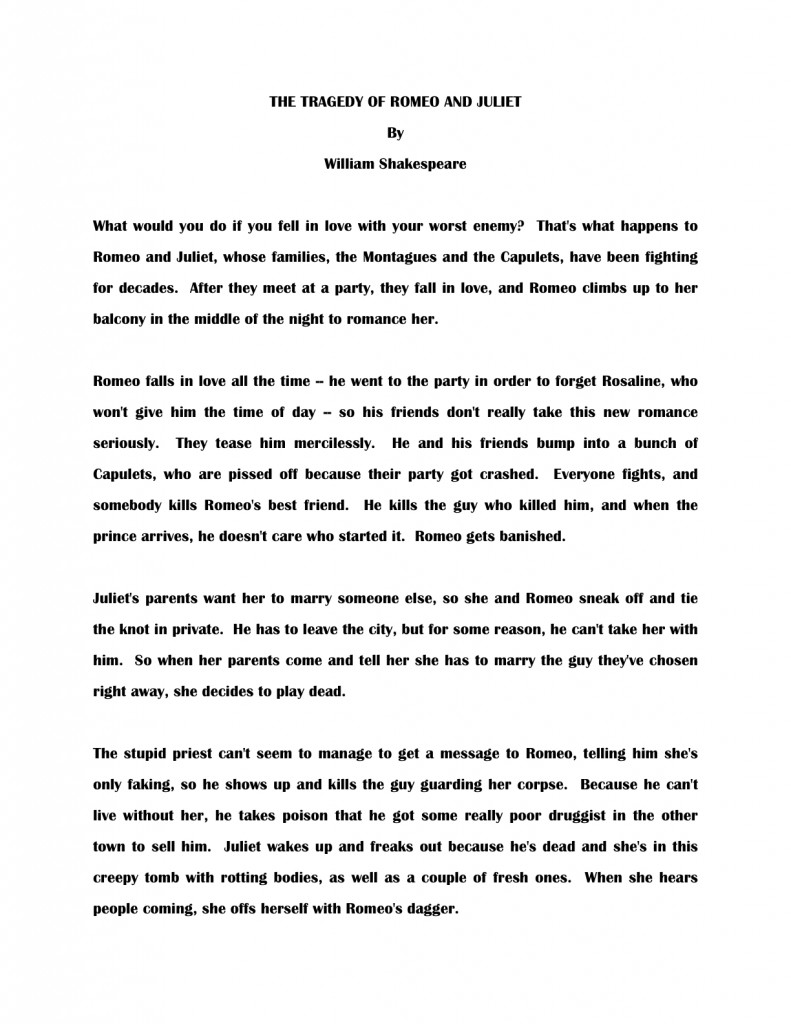

Everyone finding everything with relative ease so far? Excellent. In order to zoom in on (5), let’s take a closer look at the first page of Chapter 1.

Got that firmly in your mind? Now let’s connect the dots.

All manuscripts are double-spaced, with 1-inch margins on all four edges. (1)

Do not even consider trying to fudge either the line spacing or the margin width. Trust me, any Millicent that’s been at it a while will instantly spot any shrinkage or expansion in either. The same holds true of using any font size other than 12 point, by the way.

The text should be left-justified, not block-justified.

This one often confuses writers, because text in newspapers, magazines, and some published books is block-justified: the text is spaced so that every line in the same length. The result is a left margin and a right margin that visually form straight lines running down the page.

But that’s not proper in a book manuscript. As we see here, the left margin should be straight (2), while the right is uneven (3).

Every page of text should feature a standard slug line in the header (4), preferably left-justified.

That’s the bit in the top margin of each page containing the Author’s Last Name/Title/#. As you can see here, the slug line should be in the header — in other words, in the middle of the one-inch top margin — not on the first line of text.

The slug line should appear in the same plain 12-point type as the rest of the manuscript, by the way. No need to shrink it to 10 point or smaller; Millicent’s too used to seeing it to find it visually distracting.

The page number (5) should appear in the slug line and nowhere else on the page.

Another one that often confuses writers new to the biz: word processing programs are not, after all, set up with this format in mind. Remember, though, that the fine people at Microsoft do not work in the publishing industry, and every industry has the right to establish its own standards.

Every page in the manuscript should be numbered. The first page of text is page 1.

Do not scuttle your chances submitting an unpaginated manuscript; 99% of the time, it will be rejected unread. Yes, even if you are submitting it via e-mail. People who read for a living consider unnumbered pages rude.

The first page of a chapter should begin a third of the way down the page (6), with the chapter number (7) and/or title (8) centered at the top.

If the chapter does not have a title, just skip line (8).

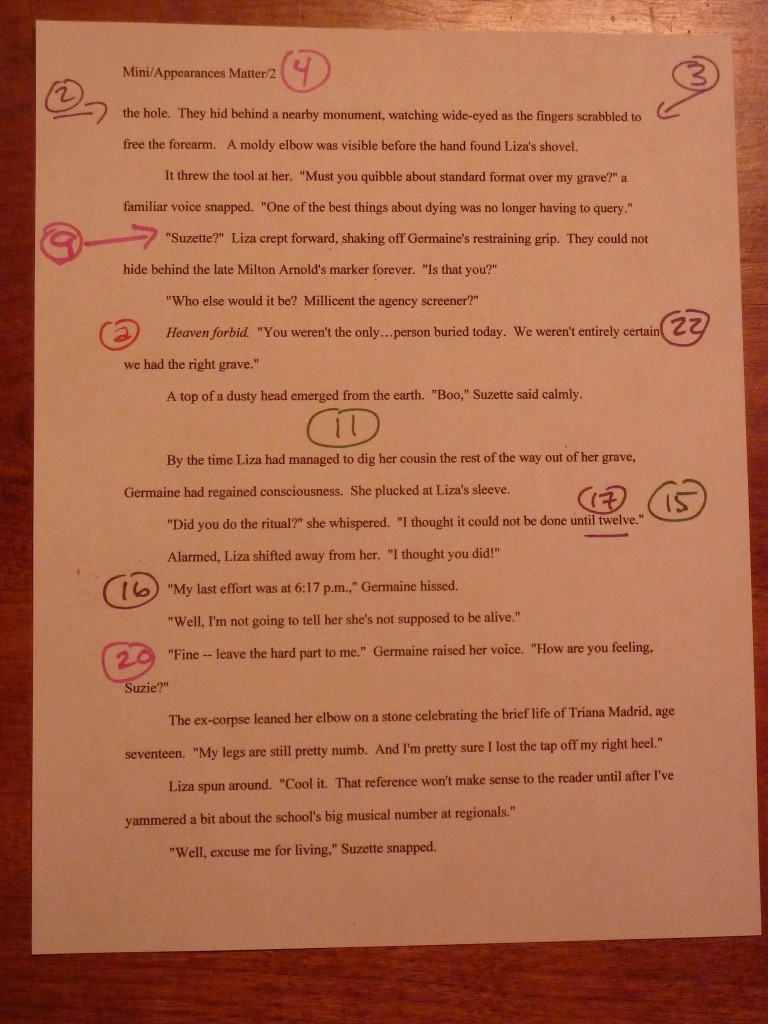

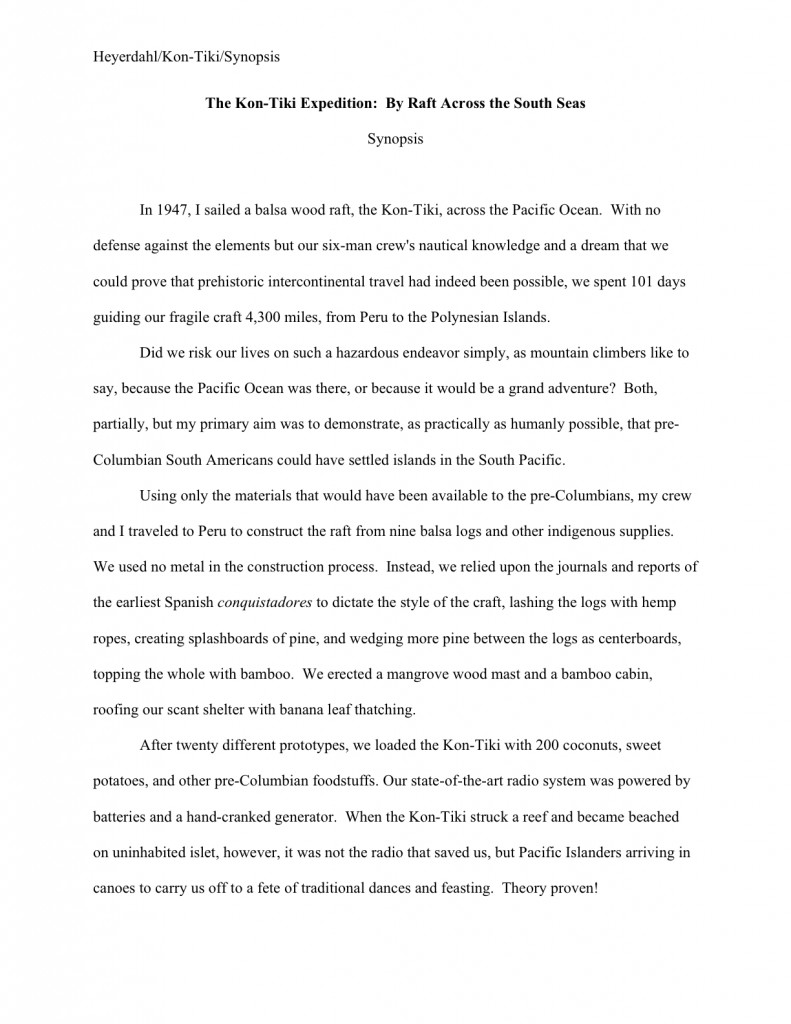

Is everyone comfortable with what we have covered so far? If not, please ask. While I’m waiting for trenchant questions, I’m going to repost page 2, so we may contemplate its majesty.

Awesomely bland, is it not? Let’s check out the rest of the rules.

The beginning of each paragraph should be indented .5 inch. (9)

Yes, including the first paragraph of each chapter, no matter what you have seen in a published book. The decision not to indent the first paragraph of the chapter rests with the publisher, not the writer; if you have strong preferences on the subject, take it up with the editor after you have sold the book.

It may seem counterintuitive, but the manuscript is not the right place to express those preferences. No formatting choice in the manuscript will necessarily end up in the published book.

That includes, by the way, an authorial preference for business format. If you happen to prefer non-indented paragraphs that force a skipped line between paragraphs, too bad. Which leads us to…

Don’t skip an extra line between paragraphs (10), except to indicate a section break. (11)

As we see here, section breaks are formed by skipping one double-spaced line. Do not indicate a section break by # # # or any other marker UNLESS you are writing a short story, article, or entering a contest that requires the inclusion of a specific symbol. (Check the rules.)

Words in foreign languages should be italicized (12), as should emphasized words (13) and titles of copyrighted works like songs (14). Nothing in the text should be underlined.

This one’s pretty self-explanatory, I think, except for the always-burning question of whether to italicize thought (as I’ve done here at a) or not. There is no hard-and-fast rule on this one: some agents like it, some consider it a narrative cop-out. Because its acceptability varies wildly between book categories, your best bet is to check five or ten recent releases similar to yours to see if italicized thought appears there.

If you ultimately decide to embrace the italicized thought convention, you must be 100% consistent in applying it throughout the text. What you should never do, however, is make the common mistake of both saying that a character is thinking something and italicizing it. To an agent or editor, this

I’m so frightened! Irma thought.

is redundant. Pick one means of indicating thought and stick to it.

All numbers under 100 should be written out in full: twenty-five, not 25. (15)

This one is not quite as straightforward as it sounds. As we can see in the text, dates, times, and currency is sometimes expressed as numbers. When a time is specific (16), it is written in number form, but a general time (17) is written out in full. September 4, 1832 is fine, but without the year, the fourth of September is correct. By the same token, a specific amount of money (18) is in numeral form, but a round number (19) is conveyed in words.

Dashes should be doubled (20), with spaces at either end, but hyphens are single, with no spaces. (21)

Why? So a typesetter can tell them apart. (Okay, so that made more sense when manuscripts were produced on typewriters. Humor Millie on this one.)

#22 is not precisely a formatting matter, but manuscript submissions so often misuse them that I wanted to flag it here. In American English (and thus when submitting to a US-based agency), ellipses contain only three periods UNLESS they come at the end of a quote that ends in a period. When an ellipsis indicates a pause in speech, as it does here at (22), there should not be a space between it and the words around it.

And that’s it! Unless an agency’s submission guidelines specify some other formatting preferences, you will not go wrong with these.

I shall now tiptoe quietly away, so you may study them in peace. Tune in tomorrow for more discussion of title pages, and, as always, keep up the good work!

P.S.: there’s a good discussion in the Comments section about formatting quotes and citations in manuscripts and book proposals.