Hard to believe anyone in his right mind would actually need to be told that those are gumballs, isn’t it? They strike me as the epitome of the breed: large, spherical, colorful, and — dare I say it? — potentially jaw-breaking. Yet clearly, at some point in the probably not-too-distant past, some passing myopic presumably asked the proprietor, “What are those, gumballs?”

Or maybe it was not a solitary forgetter of much-needed spectacles, or even a half-dozen passers-by with a shared clawing, pathological need to have even their most mundane personal observations confirmed by external sources. Perhaps the poor proprietor simply got tired of answering the same question 4,217 times per week and slapped up a sign.

Those of us who work with manuscripts for a living can sympathize. Merely breathing an editor (or my preferred title, a book doctor), preceded by the pronoun I and the verb to be in quick succession, anywhere in the vicinity of someone harboring even the slightest urge to pen the Great American Novel is to invite an avalanche of questions about manuscripts: how to get them published, how to position them under the eyes of an agent, how to keep them from getting rejected, and, surprisingly often, what they should look like.

Perfectly reasonable questions all, of course: no writer, regardless of how many times the Muses may have whacked her with their talent wands, is born knowing all about the practical aspects of manuscript production. As Plato suggests in his Theaetetus (oh, you thought I was just a pretty face?), in order to recognize something for what it truly is, one first must have a mental image of that thing with which to match it.

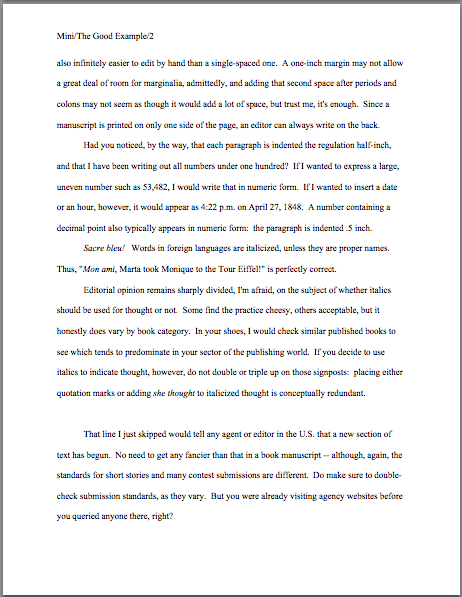

To put it a trifle less esoterically: it’s much, much harder to make your pages look right if you’ve never seen a professionally-formatted book manuscript. Call me zany, but in my experience, the best remedy for that is to show aspiring writers — wait for it — a few dozen examples of professionally-formatted book manuscript pages, rather than making them guess.

In close-up, even, as in the first post in this series. I like to think of this endeavor as both pleasing to ol’ Plato and a serious contribution to, if not the future of literature, at least to human happiness. Too many good writers have gotten rejected over the years for not being aware of the rules, or even that rules exist.

Look, kid, here’s a gumball. Study it well, so you may recognize it in the wild.

I know: how nice would it have been had some kind soul discreetly pulled you aside 35 seconds after you first decided to write a book and explained that to you, right? If you’re like most writers, it would have saved you a tremendous amount of time and chagrin to have known before you sat down to compose page 1 that since (a) all professional book manuscripts in the U.S. look more or less alike and (b) any writer who has worked with an agent or publisher would presumably be aware of that, (c) those of us who read for a living can often tell just how long an aspiring writer has been at it by the briefest glance at the page. Thus, contrary to what virtually every aspiring writer completely reasonably presumes at first, (d) one of the best things you can do to get your writing taken seriously by the pros is to format it according to their expectations.

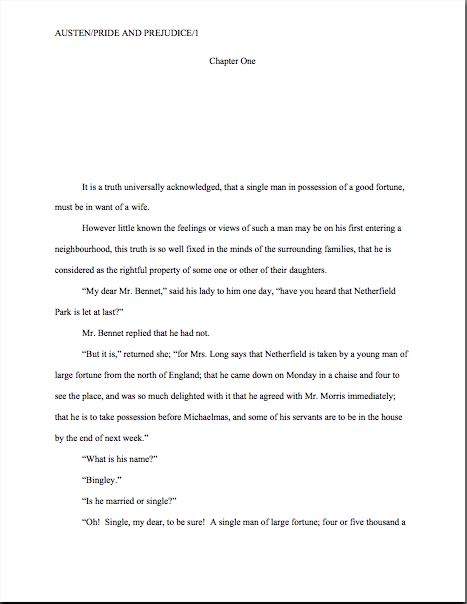

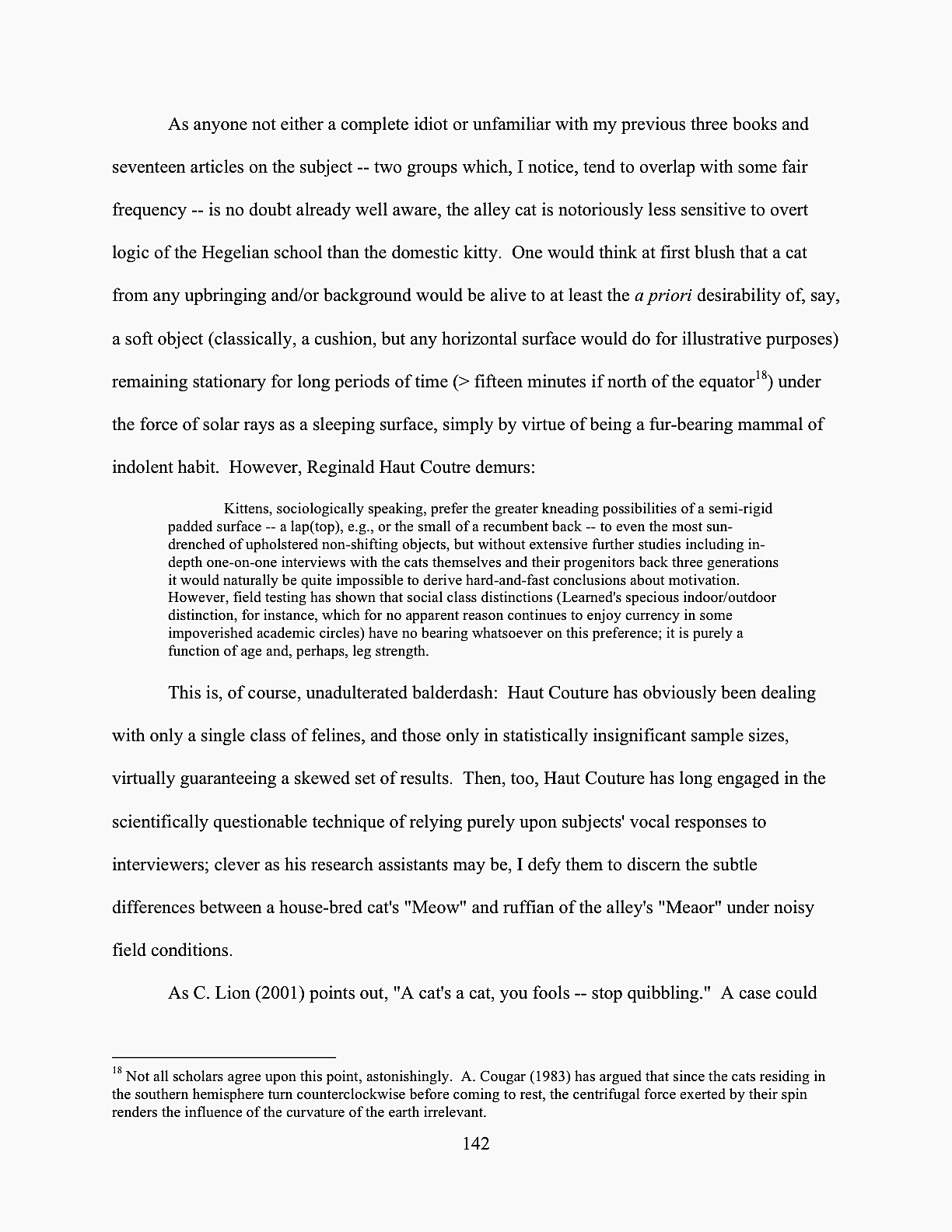

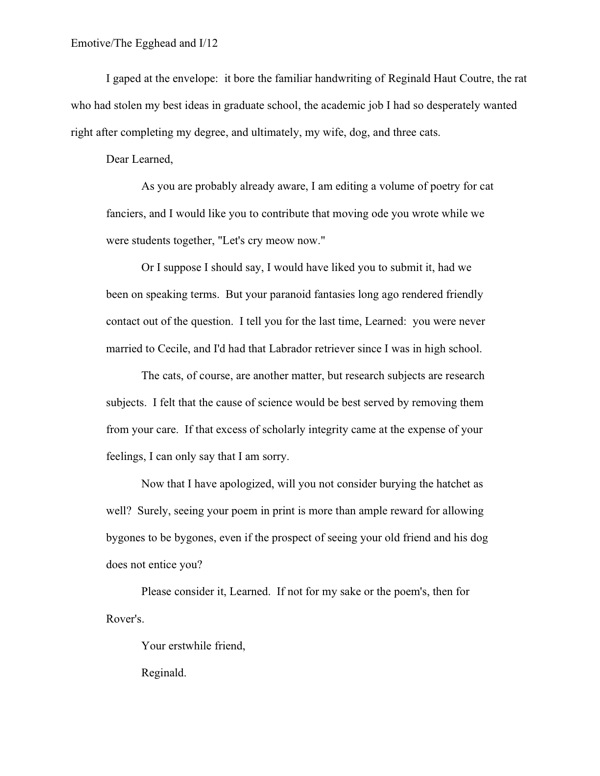

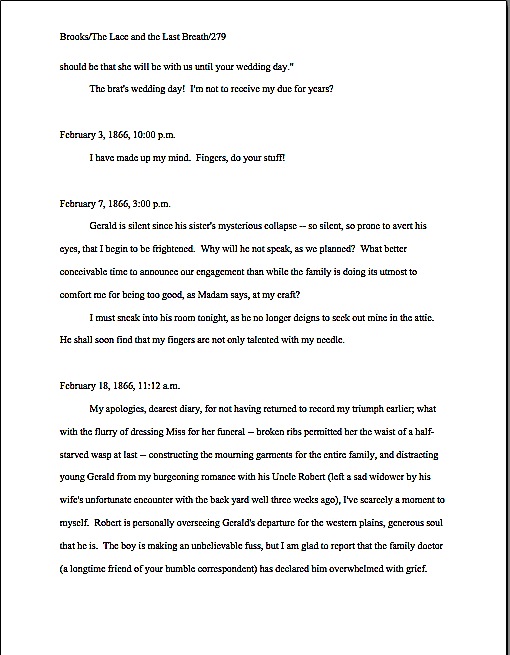

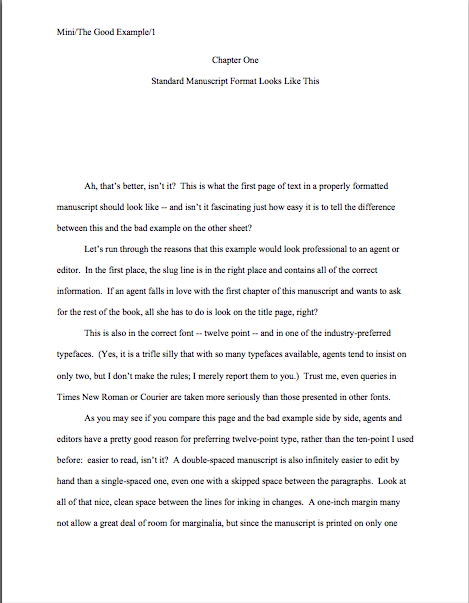

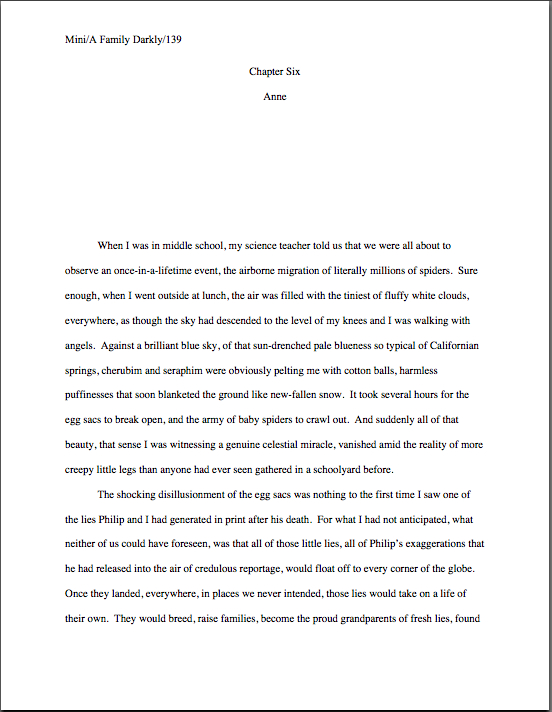

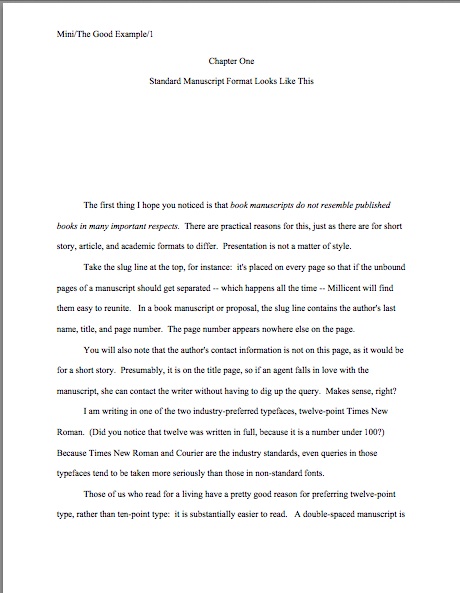

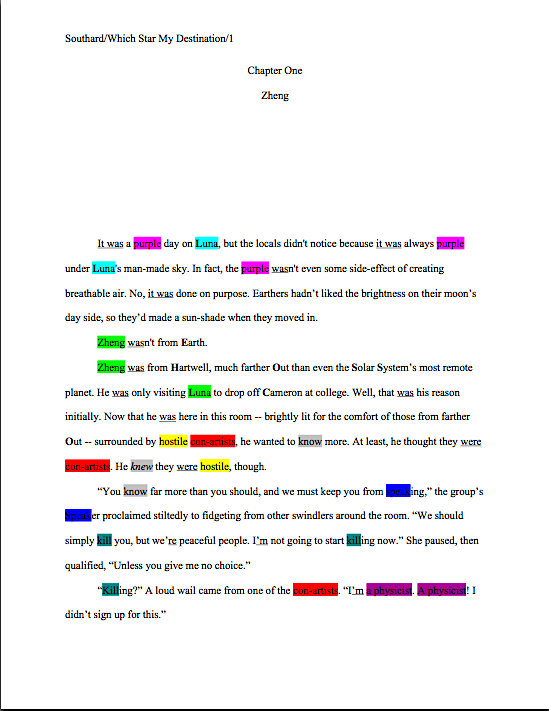

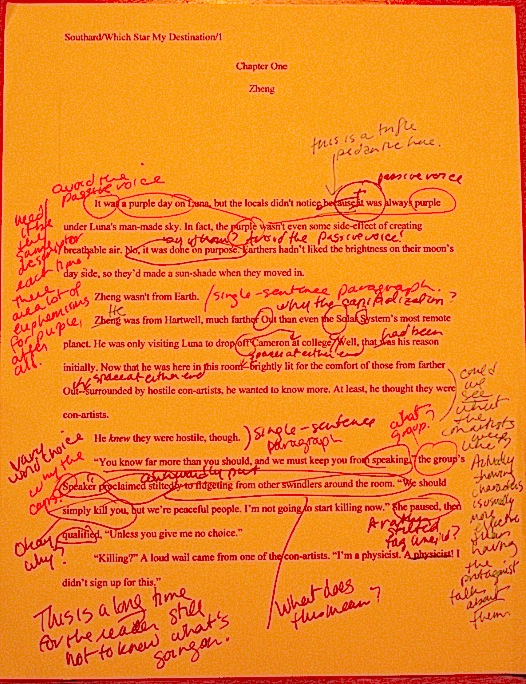

Let me guess, though: you did not tumble squalling into this world knowing any of that, did you? The weird thing is that neither were agents, editors, contest judges, or screeners. Once you’ve had the benefit of seeing a few hundred thousand correctly-formatted manuscript pages, however, you don’t even have to look very hard to notice the difference between a page 1 like this:

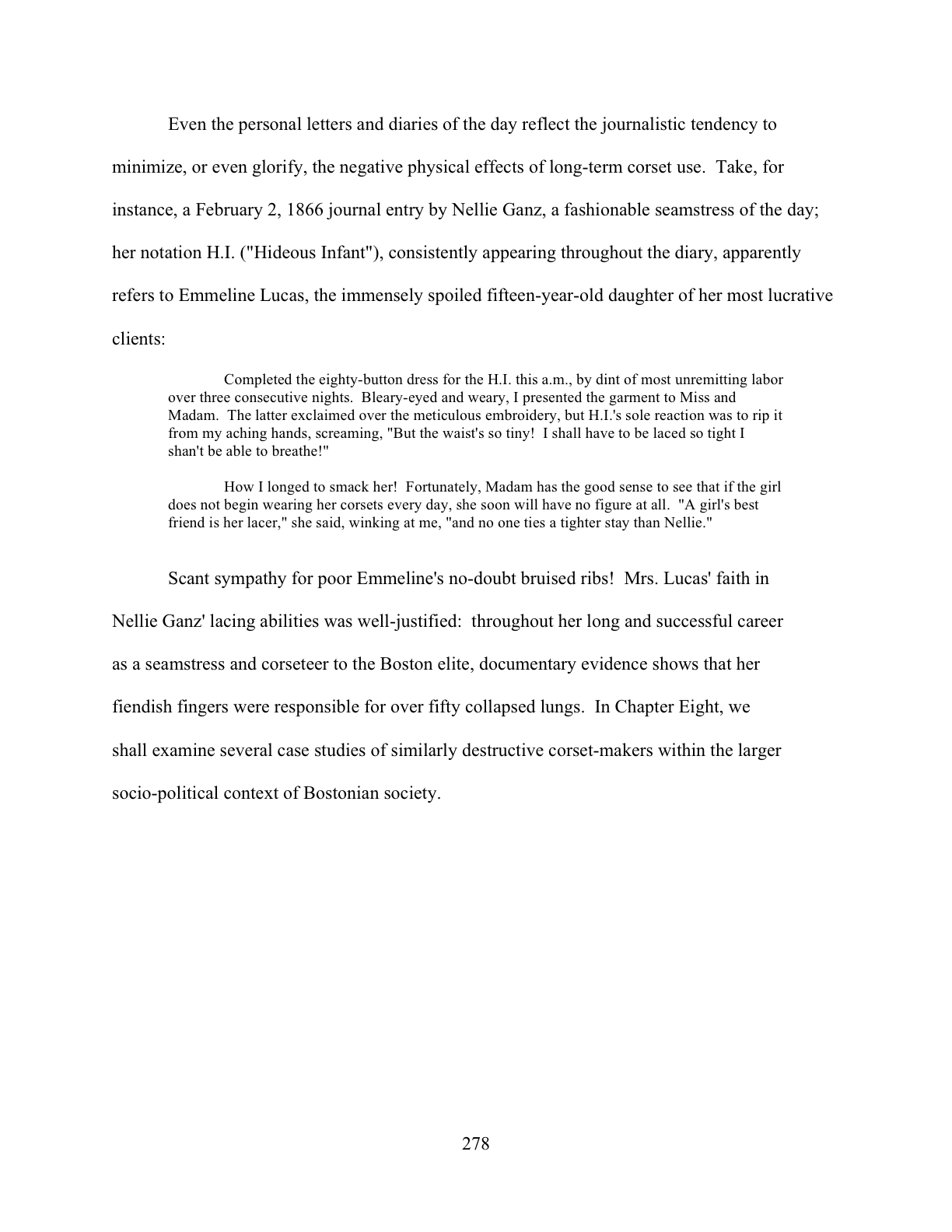

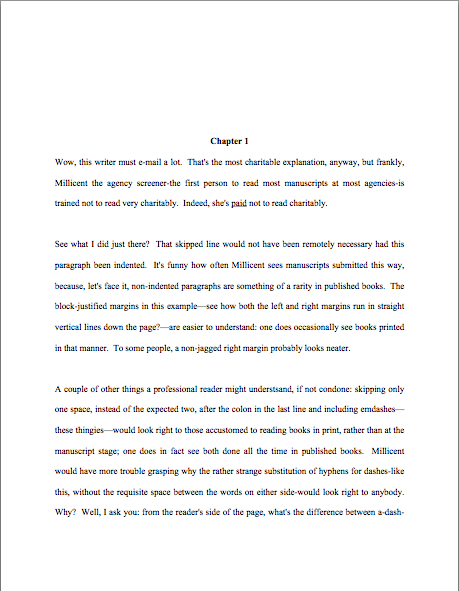

And one that looked like this:

You can see the difference from halfway across the room, can you not? So, as it happens, can Millicent the agency screener, her boss, the agent of your dreams, and the editor who will someday, the Muses willing, acquire your book. That’s the inevitable result of experience. Year in, year out, come rain, shine, or hailing wildcats, we cast our eyes over book manuscripts done right and, well, the other kind.

And that, in case any of you perplexed by how much of the information about manuscript formatting floating around out there seems to come from somewhere in the ether, rather than directly from, say, an agency or a publishing house, is why professional readers don’t spend much time doing what I’m sure a lot of aspiring writers positively long for us do, policing the Internet for rogue advice on manuscript formatting. Why would someone who already familiar with the rigors and beauties of standard format bother to look it up online, much less fact-check?

We already know a properly-formatted page when we see it — and when we don’t. “What do you mean — are those gumballs?” we mutter, incredulous. “Isn’t it self-evident?”

So strongly do some of us have the Platonic standard manuscript page in mind that it might not even occur to us that, say, there exist writers in the English-speaking world not aware of what a slug line is. It astounds us to hear that indented paragraphs are not the automatic choice of every literate person. It makes sense to us that, as much as anyone might want to conserve paper, submitting a manuscript printed on both the front and back sides and/or — sacre bleu! — spiral- or perfect-bound would generally result in its being rejected unread.

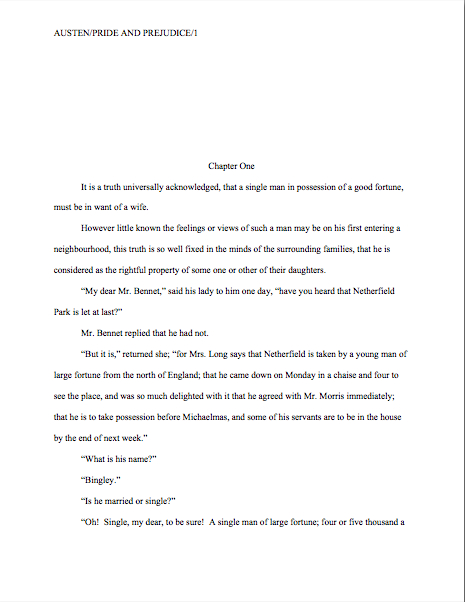

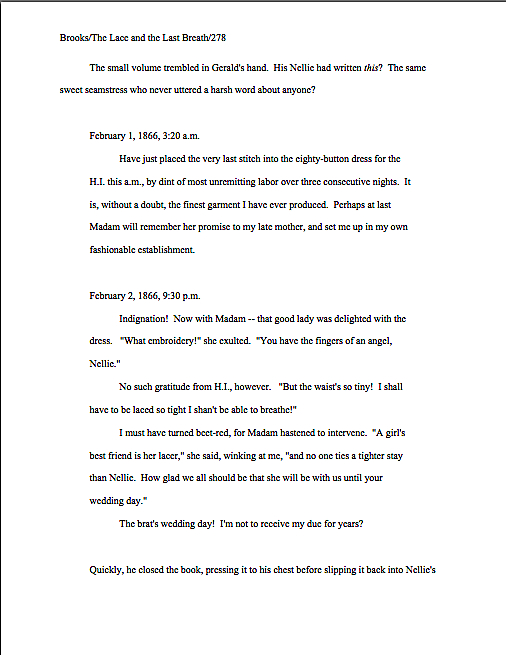

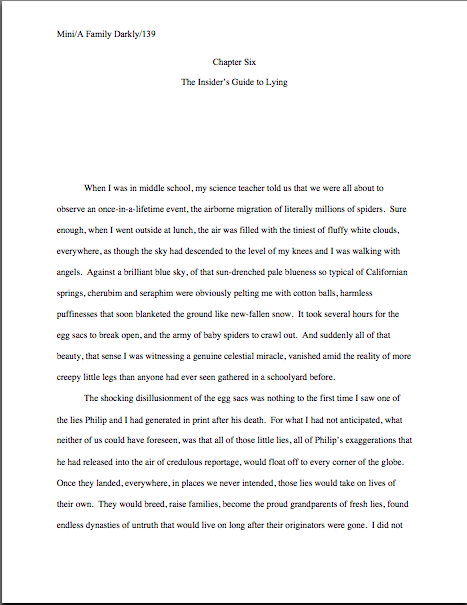

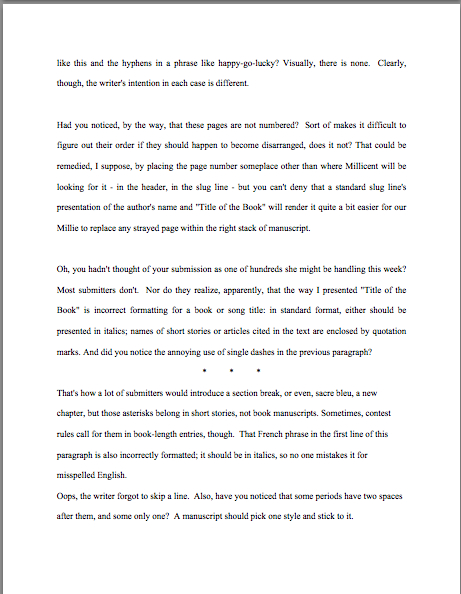

Because we are so steeped in the standard format tradition, even the smallest deviation from it draws our attention like the lone zebra in a crowd of centaurs. How could it not affect our perception of a writer’s eye for detail to discover that s/he apparently thought her page 2 would look better like this:

Than like this:

Less obvious that time, wasn’t it? Still, I suspect you were unlikely to confuse the bona fide gumball with the stick of spearmint. Unless, of course, you’d heard someplace that the last thing Millicent ever want to see in gum is a spherical shape.

Oh, don’t bother to deny it — most aspiring writers glean at least a bit of misinformation while constructing their first book-length manuscripts. How do I know? Those of us who spend any time at all around aspiring writers find ourselves constantly in the position of being asked to confirm what to us has become through long experience self-evident. Even more often, we’re called upon to defend the shape of the Platonic gumball to those who have heard somewhere that even so much as a curled-up edge will result in instant and contemptuous rejection.

“What do you mean, paragraphs have to be indented?” writers who have entertained alternate theories often snap at us, flabbergasted. “I’ve heard that’s considered old-fashioned now. And are you mad, recommending doubled dashes?”

Since either of those formatting innovations would be news to folks who read manuscripts for a living, it can be a bit trying to be told otherwise, sometimes at ear-splitting volumes, early and often. Even as a great proponent of explanations as yours truly tends to find it wearying the 87th time in any given month that a total stranger burning for publication accosts me like the Ancient Mariner, wanting to spend two hours arguing about the latest rumor flying around the web about how standard format has abruptly altered in some fundamental-yet-mysteriously-secret manner rightly understood by only whatever generous soul chose to promulgate the change.

No one knows who this public benefactor is, of course; aspiring writers seeking confirmation of such rumors name their sources so seldom that by the turn of the century, I had begun to think of them collectively as He Who Must Not Be Named. (Take that, Voldemort!) In recent years, however, I have rechristened this shadowy figure by the name his proponents must often cite: But I heard…

But I Heard is an insidious opponent, believe you me, as only a faceless entity can be — he seems to be everywhere. His power, as nearly as I can tell, stems almost entirely from his amorphousness. Because it’s impossible to find out where he’s getting his ostensibly inside information, no amount of proof can refute his arguments to his adherents’ satisfaction; because he so seldom explains himself, logic has been known to bounce right off him and hit innocent bystanders. And that’s kind of annoying to those of us who juggle manuscripts on a daily basis, because But I Heard seems to be retailing some pretty wacky notions these days.

That puzzles the pros: standard format for manuscripts actually hasn’t changed all that much since Saul Bellow was a callow youth, much less since he shuffled off this mortal coil. Once typed manuscripts became the norm, standard format pulled up a chair and stayed for a while. And contrary to astoundingly popular opinion, it has shifted in its seat relatively little since Truman Capote joined the choir invisible.

But that’s not what you’ve heard, is it? The rise of the personal computer has made less of a difference than But I Heard would have you believe. Oh, underlining is out and italics are in to designate words in foreign languages (in the post-Capote universe, one should never underline anything in a book manuscript; I’ll be getting to that), and how one actually figures out how much to indent a paragraph has altered a bit with the adoption of Microsoft Word as the industry standard for electronic submission (unlike a typewriter, Word measures its tabs in fractions of an inch, not character spaces). Overall, though, the professionally-formatted book manuscript of today quite closely resembles the professionally-formatted book manuscript of, say, 1958.

Which is to say: not very much like the short stories of that very good year for short stories. The gumball’s shape has not altered much over that period, either.

The relative lack of change, But I Heard tells me, is far from self-evident. He would prefer to believe that all writing should be formatted identically, regardless of type. In that, alas, he is misinformed: short story format is different from standard format for books and book proposals, and has been for quite some time. So are essay format, academic format, journalistic format, and even how a published book will look on a page.

That very notion makes But I Heard squirm. But that’s not going to stop me from saying what I know from experience to be true: book manuscripts presented in standard format look professional to people who handle book manuscripts for a living. If those are the people a writer is trying to please, does it really matter what anybody else thinks writing should look like on the page?

Does that mean every professional reader, everywhere, every time, will want to see your work formatted as we have been discussing? No, of course not: should you happen to be submitting to an agent, editor, or contest that specifically asks you to do something other than I advise here, obviously, you should give him, her, or it what he or his stated guidelines request.

That’s just common sense, right? Not to mention basic courtesy. Yet judging by the plethora of ambient speculation on the subject, it’s not self-evident.

Yet if an agent or agency has been considerate enough of its future clients to post submission guidelines, it just makes sense to acknowledge their efforts. I would actively encourage every writer currently milling about the earth’s crust not only to check every agency’s website, every time, to make sure that any individual agent to whom you were planning to submit does not harbor alternate preferences — some do — but also to Google him, to double-check that he hasn’t stated in some public forum that, for instance, he is so deeply devoted to paper conservation that he actively prefers only a single space after a period or a colon. Or that due to a childhood trauma involving a newspaper (she doesn’t like to talk about it), she positively twitches at the sight of Times New Roman instead of Courier. Or that a particular agency’s staff believes that a doubled dash is the secret symbol of the kind of murderous cult that used to populate 1970s horror movies.

Really, though, if the agent of your dreams says he wants to see your submission formatted a particular way, can you think of any particular reason you wouldn’t want to honor that preference?

“I can think of one!” But I Heard shouts. “It would be considerably less work to format my manuscript once and submit it that way to every agent currently drawing breath, rather than taking the time to hunt down a specific agent’s expressed preferences, saving a separate copy of one’s manuscript, applying those preferences to it (and only it), and sending a personalized version to that agent. Why, think of how time-consuming to go through those same steps for every agent, every time!”

It might be, if alternate preferences were either widespread (they’re not, particularly) or often posted on agency websites (see previous parenthesis). At the risk of repeating myself, standard format is called that for a reason.

But I Heard certainly has a point, though. He also has, as you may have noticed over the years, an exceedingly simple means of promoting that point and ones just like it: by leaping to the conclusion that because one has a strong preference for a non-standard format element, every agent or agency must necessarily have tossed all previous norms to the winds in order to embrace that preference. And, for reasons best known to themselves, they’ve elected not to notify any working author you might care to mention about this monumental collective decision, preferring instead to disseminate the information via the much more reliable and trustworthy game of Telephone.

You remember that game, right? The first kid whispers a secret to the person next to her; #2 repeats what he heard to #3, and so on around the circle. By the time the news has passed through a dozen pairs of lips, the original content has become so transfigured in transit that it’s hardly recognizable.

I hate to spoil But I Heard’s good time — there’s little he likes better than inflating something someone said someone else overhead an agent said say at a conference once upon a time into the new trend sweeping the nation — but personal preferences do in fact exist. And contrary to what you might have heard, agents and agencies that favor specific deviations from standard format tend not to be all that shy about mentioning them.

In case I’m being too subtle here: check their websites. Or their listings in one of the major guides to literary agents.

Do I spot some timid hands raised out there in the ether? “But Anne,” point out some confused by conflicting advice — and who could blame them, given how busy But I Heard has been in recent years? “I’ve been checking websites, and the overwhelming majority of agency websites I’ve found don’t talk about manuscript format at all. Does that mean that they don’t care about how I present my writing?”

Of course, they care, but standard format is just that: standard. If what they want is a gumball, why should they take the time to explain that they don’t desire a bar of chocolate?

Yes, But I Heard? You would like to add something? “I get it,” he moans, rattling the Jacob Marley chains appropriate to his disembodied state. “All my long-time nemesis, Millicent the agency screener, cares about in a submission is how it looks, not how it is written. How literature has tumbled from its pedestal! No one cares about good writing anymore!”

Did you see what that dastardly wraith just did to my non-threatening piece of sugar-laden analysis? But I Heard is a past master at ripping statements out of context, blowing them out of proportion, and whisking them off to parts unknown to their original utterers. But you’re too savvy, I’m sure, to join him in the wild surmise that Millicent’s paying attention to how a manuscript looks means, or even implies, that how a submission is written doesn’t make a difference. Of course, writing talent, style, and originality count. Yet in order to be able to appreciate any of those properly, a reader has to approach the page with a willingness to be wowed.

That willingness can wilt rapidly in the face of incorrect formatting — which isn’t, in response to what But I Heard just shouted in your ears, necessarily the result of mere market-mindedness on Millie’s part. After you’ve read a few thousand manuscripts, deviations from standard format leap out at you. As will spelling and grammatical errors, phrase repetition, clich?s, telling rather than showing, and all of the tried-and-true submission red flags about which But I Heard has been kind enough to keep us informed over the years.

Again, he has a legitimate point: all of these are distractions from your good writing. So, as it happens, are deviations from standard format, to a reader used to seeing writing presented that way. That means, in practice, that presenting your manuscript as Millie expects to see it is the way that she is least likely to find distracting.

What does she see if you present your manuscript as she expects to see it? Your writing.

I hear those of you who have spent years slaving over your craft groaning — believe me, I sympathize. For those of you who have not already started composing your first drafts in standard format (which will save you a lot of time in the long run, incidentally), many of the tiny-but-pervasive changes I am about to suggest that you make to your manuscript are going to be irksome to implement. Reformatting a manuscript is time-consuming and tedious, and I would be the first to admit that at first, some of these rules can seem arbitrary.

At least on their faces. Quite a few of these restrictions remain beloved even in the age of electronic submissions because they render a manuscript a heck of a lot easier to edit — and to read, in either hard or soft copy. As I will demonstrate with abundant examples later in this series, a lot of these rules have survived for completely practical purposes — designed, for instance, to maximize white space in which the editor may scrawl trenchant comments like, “Wait, wasn’t the protagonist’s brother named James in the last chapter? Why is he Aloysius here?”

Ready to take my word for that in the meantime? Excellent; help yourself to a gumball. Let’s recap the rules we covered last time:

(1) All manuscripts should be printed or typed in black ink and double-spaced, with one-inch margins around all edges of the page, on 20-lb or better white paper.

(2) All manuscripts should be printed on ONE side of the page and unbound in any way. For submission to US-based agencies, publishing houses, and contests, the pages in question should be US-standard 8.5″ x 11″ paper.

(3) The text should be left-justified, NOT block-justified. By definition, manuscripts should NOT resemble published books in this respect.

(4) The preferred typefaces are 12-point Times, Times New Roman, Courier, or Courier New — unless you’re writing screenplays, in which case you may only use Courier. For book manuscripts, pick one (and ONLY one) and use it consistently throughout your entire submission packet.

Is everyone happy with those? If not, I await your questions. While I’m waiting, however, I’m going to move on.

(5) The entire manuscript should be in the same font and size — no switching typefaces for any reason. Industry standard is 12-point font.

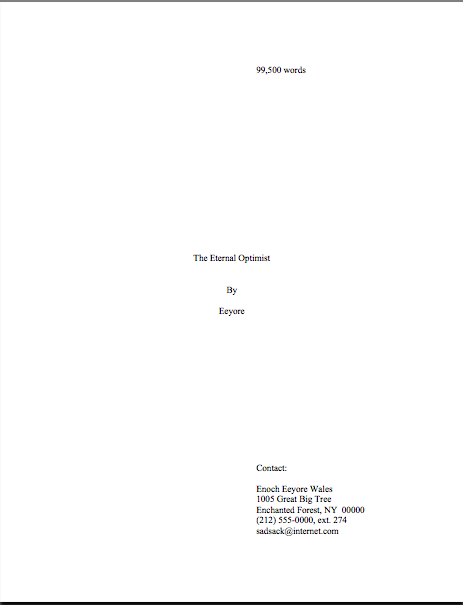

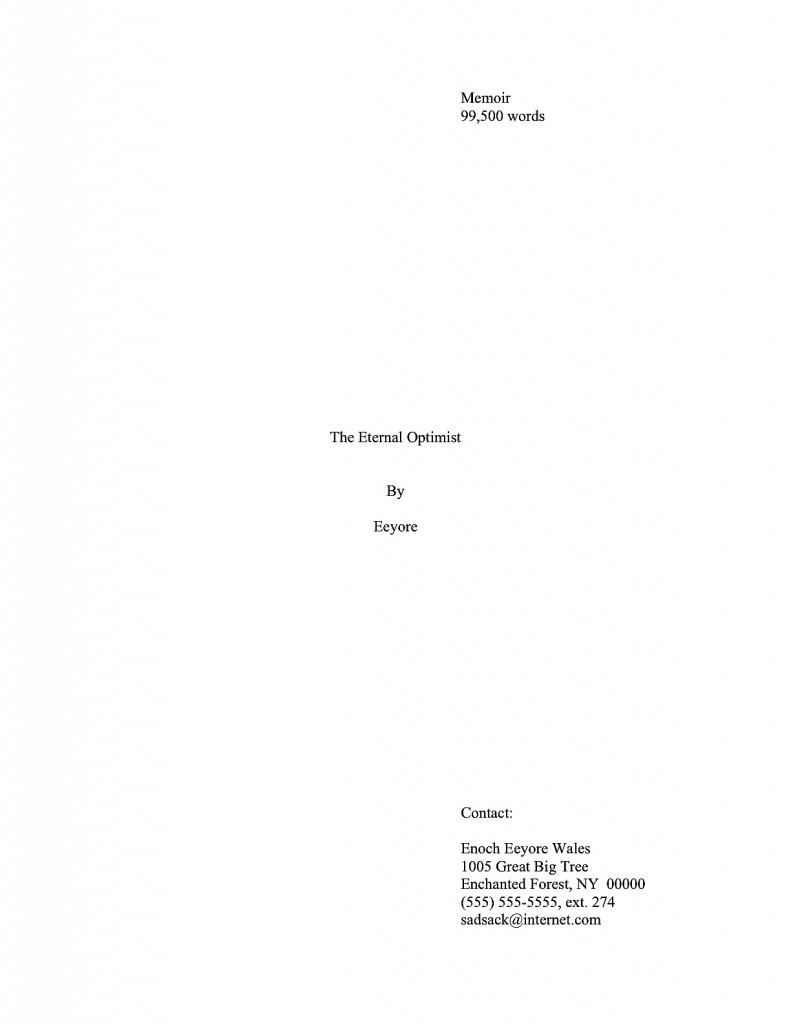

No exceptions, please. No matter how cool your favored typeface looks, be consistent. Yes, even on the title page, where almost everyone gets a little wacky the first time out.

No pictures or symbols here, either, please. Just the facts. I hate to be the one to break it to you, but there’s a term for title pages with 24-point fonts, fancy typefaces, and illustrations.

It’s high school book report. Need I say more?

(6) Do not use boldface anywhere in the manuscript but on the title page — and not even there, it’s not a particularly good idea.

This seems like an odd one, right, since word processing programs render including boldface so easy? Actually, the no-bolding rule is a throwback to the old typewriter days, where only very fancy machines indeed could darken selected type. Historically, then using bold was considered a bit tacky for the same reason that wearing white shoes before Memorial Day is in certain circles: it’s a subtle display of wealth.

You didn’t think all of those white shoes the Victorians wore cleaned themselves, did you? Shiny white shoes denoted scads of busily-polishing servants.

You may place your title in boldface on the title page, if you like, but that’s it. Nothing else in the manuscript should be in boldface. (Unless it’s a section heading in a nonfiction proposal or manuscript — but don’t worry about that for now; I’ll be showing you how to format both a book proposal and a section break later on in this series, I promise. I shall also be tossing many, many examples of properly-formatted title pages your way, never fear.)

(7) Every page in the manuscript should be numbered, except the title page. The first page of text is page 1, not the title page.

Even if you choose to disregard literally everything else I’ve said here, please remember to number your pages. Millicent’s usual response to the sight of an unnumbered manuscript is to reject it unread.

Yes, really; this omission is considered genuinely rude. Few non-felonious offenses irk the professional reader (including yours truly, if I’m honest about it) more than an unnumbered submission or contest entry. It ranks right up there with assault, arson, and beginning a query letter with, Dear Agent instead of Dear Ms. Smith.

Why? Gravity, my friends, gravity. What goes up tends to come down. If the object in question happens to be an unbound stack of paper, and the writer who sent it did not bother to number those pages…well, picture it for yourself: two manuscript-bearing interns walking toward each other in an agency hallway, each whistling a jaunty tune. Between them, a banana peel, a forgotten skateboard, and a pair of blindfolded participants in a three-legged race clutching a basket stuffed to the brim with ping-pong balls between them.

You may giggle, but anyone who has ever worked with submissions has first-hand experience of what would happen should any two of those elements come into direct contact. After the blizzard of flying papers has subsided, and the interns rehash that old Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup commercial’s dialogue (“You got romance novel in my literary fiction!” “You got literary fiction in my romance novel!”), guess what needs to happen?

Some luckless soul has to put all of those pages back in proper order, that’s what. Just how much more irksome is that task going to be if the pages are not numbered?

Obey Rule #7. Trust me, it is far, far easier for Millicent to toss the entire thing into the reject pile than to spend the hours required to guess which bite-sized piece of storyline belongs before which in an unnumbered manuscript.

Wondering why the first page of the text proper is page 1 of the text, not the title page, and should be numbered as such? Or why, if your opus has an introduction or preface, the first page of that is page 1, not the first page of chapter 1?

Long-time readers, pull out your hymnals and sing along: because gumballs are round, and books manuscripts do not resemble published books.

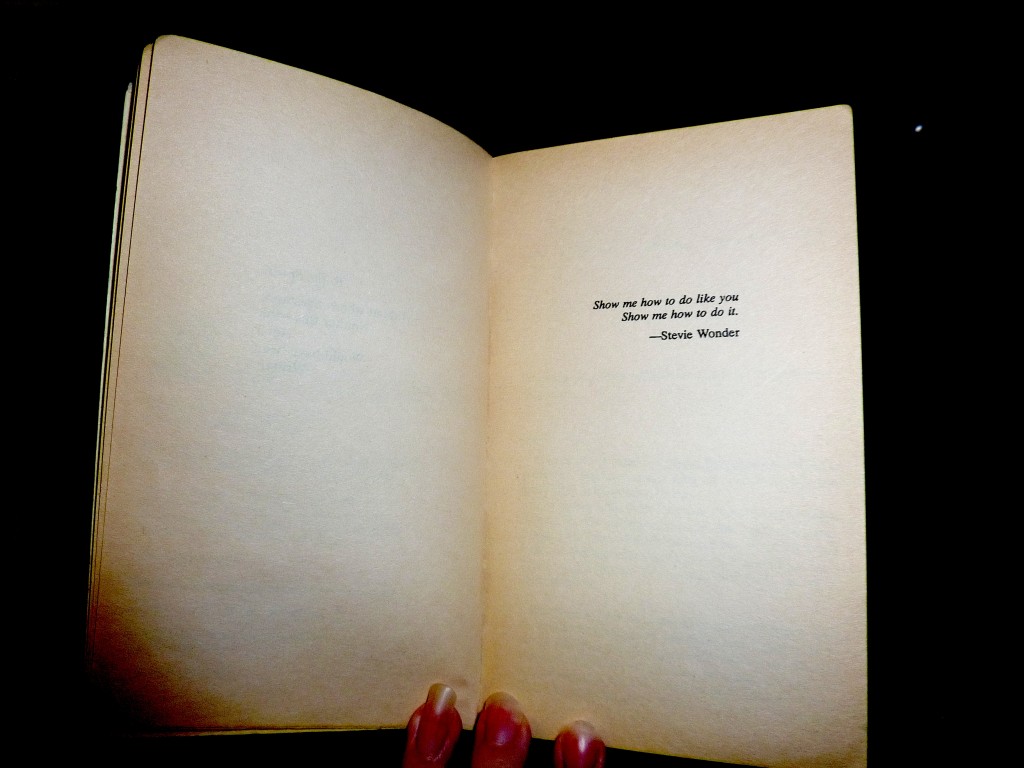

The title page is not the only one commonly mislabeled as 1, by the way: epigraphs — those quotations from other authors’ books so dear to the hearts of writers everywhere — should not appear on their own page in a manuscript, as they sometimes do in published books. If you feel you must include one (which you might want to reconsider at the submission stage: 99.9999% of the time, Millicent will just skip over it), include it between the chapter title and text on page 1.

If that last paragraph left your head in a whirl, don’t worry — I’ll show you how to format epigraphs properly later in this series. (Yes, including some discussion of that cryptic comment about Millicent’s wandering peepers. All in the fullness of time, my friends.)

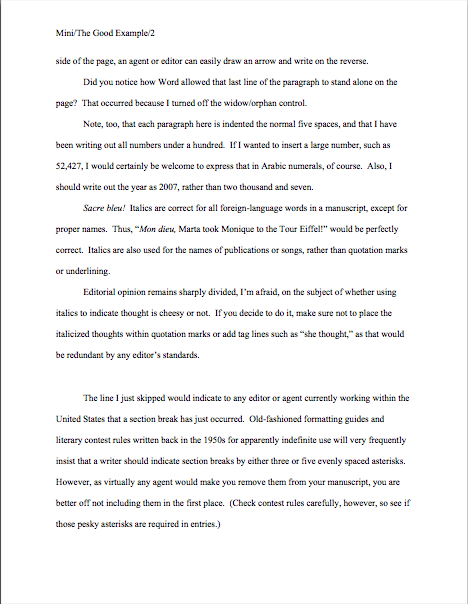

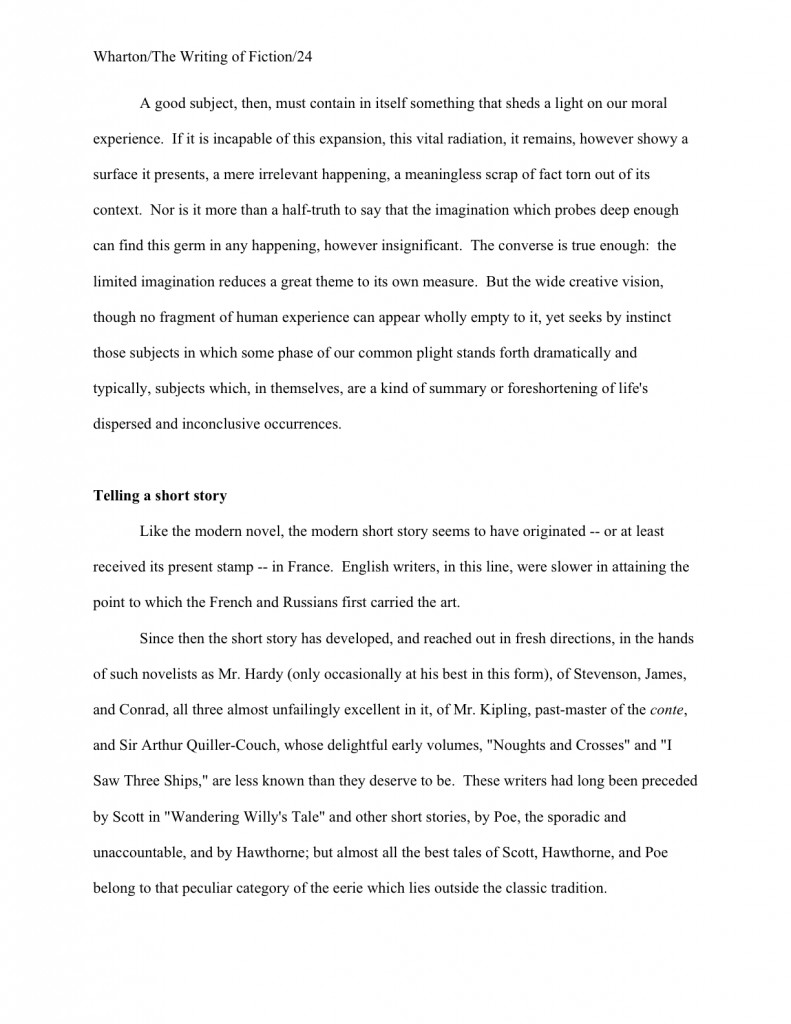

(8) Each page of the manuscript (other than the title page) should have a standard slug line in the header. The page number should appear in the slug line, not anywhere else on the page.

Including the slug line means that every page of the manuscript has the author’s name on it — a great idea, should you, say, want an agent or editor to be able to contact you after s/he’s fallen in love with it. Or be able to tell your submission from the other one that ran afoul of the banana peel in our earlier example.

The slug line should appear in the upper left-hand margin (although no one will sue you if you put it in the upper right-hand margin, left is the time-honored location) of every page of the text except the title page (which should have nothing in the header or footer at all).

A trifle confused by all that terminology? I’m not entirely surprised. Most writing handbooks and courses tend to be a trifle vague about this particular requirement, so allow me to define the relevant terms: a well-constructed slug line includes the author’s last name, book title, and page number, to deal with that intern-collision problem I mentioned earlier. (The slug line allows the aforementioned luckless individual to tell the romance novel from the literary fiction.) And the header, for those of you who have not yet surrendered to Microsoft Word’s lexicon, is the 1-inch margin at the top of each page.

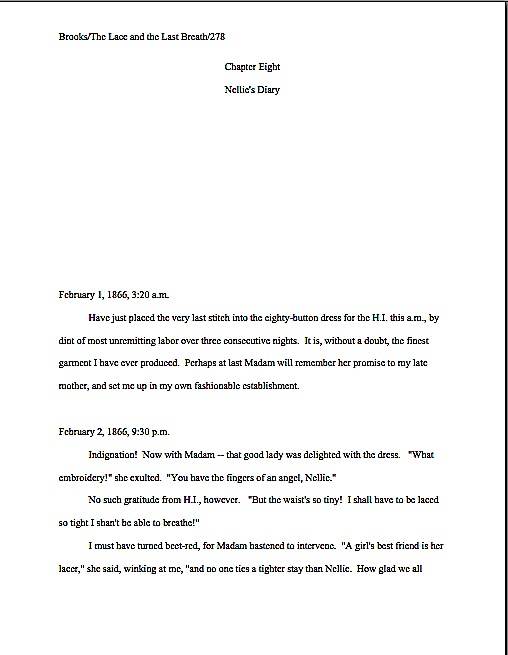

Having trouble finding it in our page examples above? Here’s a subtle hint:

Since the only place a page number should appear on a page of text is in the slug line, if you are in the habit of placing numbers wacky places like the middle of the footer, do be aware that it does not look strictly professional to, well, professionals. Double-check that your word processing program is not automatically adding extraneous page numbers elsewhere on the page.

Do not, I beg of you, yield like so many aspiring writers to the insidious temptation add little stylistic bells and whistles to the slug line, to tart it up. Page numbers should not have dashes on either side of them, be in italics or bold, or be preceded by the word page. Trust me, Millicent will know what that number is, provided that it appears here — and only here:

Sensing just a bit of urgency on this one? Good. Those of us predisposed to regard gumballs as inherently spherical are always surprised to see how many aspiring writers regard page numbering as a tempting forum for self-expression. Remember, professional readers do not regard formatting choices as matters of personal style. The point here is not to make your slug line stand out for its innovative visual impact, but to provide practical guidance in reestablishing sequence should those ping-pong balls start bouncing about underfoot.

If your book has a subtitle, don’t include it in the slug line — and if it boasts a very long title, feel free to abbreviate, to keep the slug line from running all the way across the top of the page. Millicent needs to be able to identify the manuscript at a glance, not to reproduce the entire book jacket.

Why not? Well, technically, a slug line should be 30 spaces or less, but there’s no need to stress about that in the computer age. (A slug, you see, is the old-fashioned printer’s term for a pre-set chunk of, you guessed it, 30 spaces of type. Aren’t you glad you asked?) Let’s assume for the sake of example that I’ve written a novel entitled THE SMILING FROWNER BEMUSED– 26 characters, counting spaces. Since my last name is quite short, I could get away with putting it all in the slug line, to look like this:

Mini/The Smiling Frowner Bemused/1

If, however, my last name were something more complicated, such as Montenegro-Copperfield — 22 characters all by itself, including dash — I might well feel compelled to abbreviate.

Montenegro-Copperfield/Smiling Frowner/1

Incidentally, should anyone out there come up with a bright idea for a category heading on the archive list for this issue other than SLUG LINE — a category that already exists, but is unlikely to be found by anyone not already familiar with the term — I’d be delighted to hear suggestions. I’ve called it a slug line ever since I first clapped eyes on a professional manuscript (an event that took place so long ago my response to the sight was not, “What’s that at the top of the page, Daddy?” but “Goo!”), so I’m probably not going to be coming up with a good alternative anytime soon. Thanks.

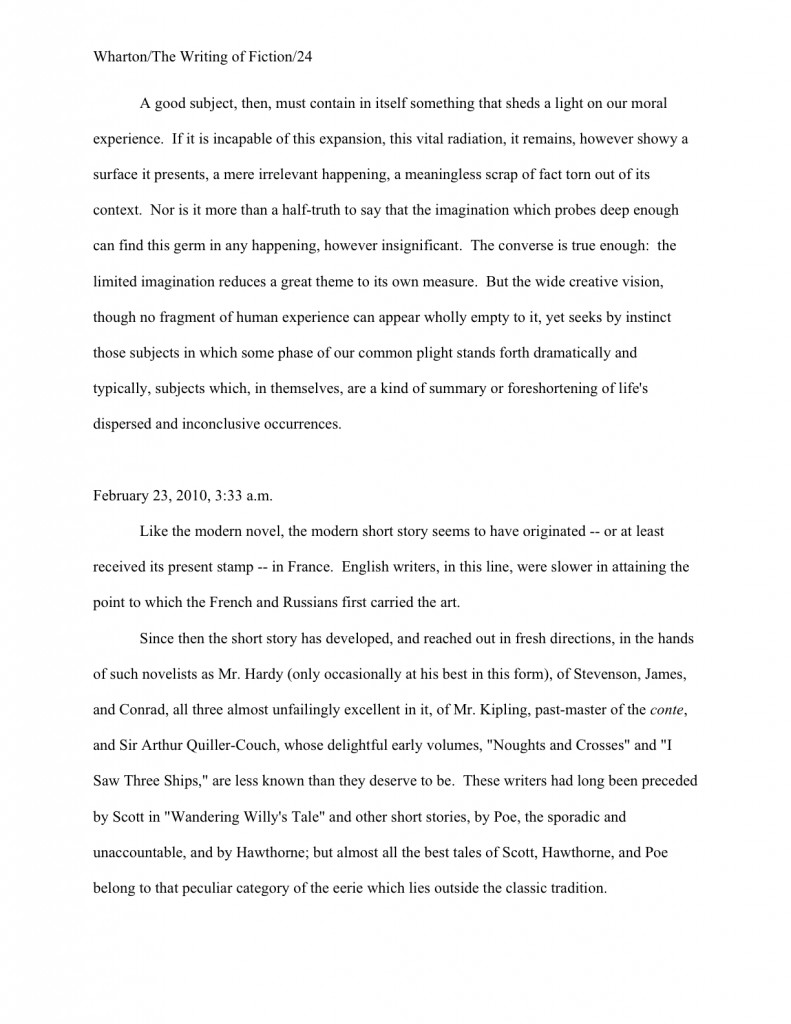

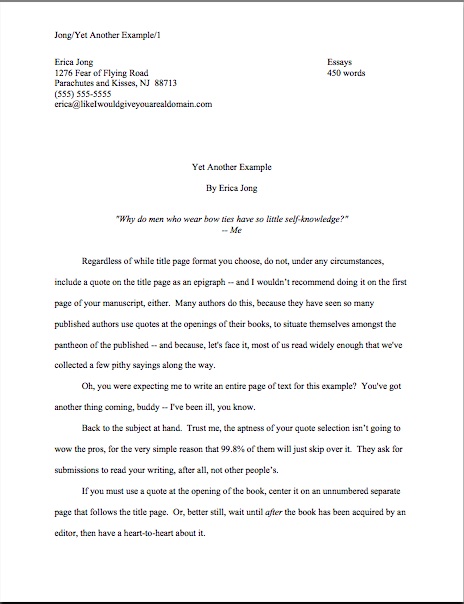

(9) The first page of each chapter should begin a third of the way down the page. The chapter title should appear on the first line of the page, not on the line immediately above where the text begins.

That’s fourteen single-spaced lines down, incidentally. The chapter title (or merely “Chapter One”) should be centered, and it should neither be in boldface nor underlined. To revisit today’s first example:

“But Anne,” But I Heard protests, “why shouldn’t the title appear immediately above the text? I’ve often seen that suggested — and illustrated online. What gives?”

Would any of you care to field that one? Perhaps someone who took the time to read the text of today’s positive and negative examples? Feel free to chant the answer with me, sharp-eyed perusers: “Because that’s where the title of a short story lives, not a book’s.”

Self-evident once you’ve heard it, isn’t it?

Because confusing the two formats is so common, very frequently, agents, editors and contest judges are presented with improperly-formatted first pages that have the title of the book, by Author’s Name, and/or the writer’s contact information floating in the space above the text. To professional eyes, a manuscript that includes any of this information on the first page of the manuscript (other than in the slug line, of course) seems like it just ended up in the wrong office. Clearly, the writer wanted not the agency to which she sent it, but the magazine down the street.

So where does all of that necessary contact information go, you ask? Read on.

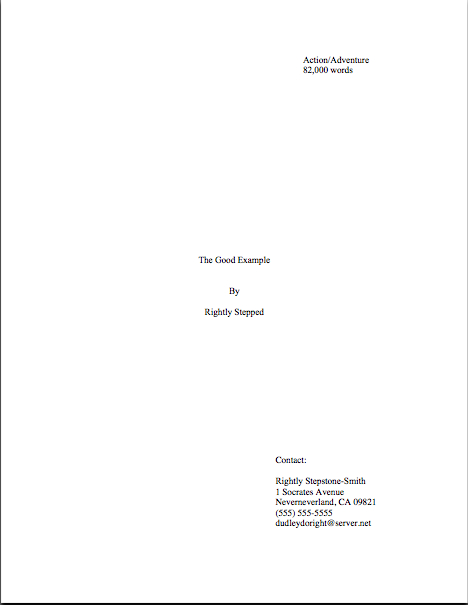

(10) Contact information for the author belongs on the title page, not on page 1.

This is one of the most obvious visual differences between a short story submission (say, to a literary journal) and a book-length manuscript. To submit a manuscript — or contest entry, for that matter — with this information on page 1 is roughly the equivalent of taking a great big red marker and scrawling, “I don’t know much about the business of publishing,” across it.

Just don’t do it. Millicent likes her gumballs.

“But wait,” I hear some of you out there murmuring, “My gumball — I mean, my manuscript — needs a title page? Since when?”

What a timely question.

(11) Every submission should include a title page, even partial manuscripts.

This one seems to come as a surprise to a lot of aspiring writers. You should include a title page with ANY submission of ANY length, including contest entries and the chapters you send after the agent has fallen in love with your first 50 pages.

And again, But I Heard expresses disgruntlement. “More work!” he cries. “If you’d only let us shoehorn our contact information onto page 1 (as I notice you have artfully resisted showing as a counterexample, lest some reader mistake it for acceptable book format), this would not be at all necessary!”

At the risk of sounding callous, so what? You want to make it as easy as humanly possible for the agent of your dreams to let you know that she wants to represent this book, don’t you? And it’s not as though she would ever dream of sending anything you wrote to an editor at a publishing house without a title page.

Yes, really. Literally every manuscript that any agent in North America submits to any editor in hard copy will include one, for the exceedingly simple reason that it’s the page that includes the agent’s contact information.

Yet, astonishingly, a good 95% of writers submitting to agencies seem to be unaware that including it is standard. I blame But I Heard: to him, the cover letter, address on the SASE, or the e-mail to which the requested materials were attached are identification enough. But in practice, it’s none of those things will necessarily still be attached to your pages at the point when your ideal agent says, “By jingo, I’m thoroughly wowed. This is a writer I must sign, and pronto!”

Oh, you thought that your SASE won’t go flying when those interns collide in the hallway? Or that e-mails never get deleted accidentally? Once those ping-pong balls get rolling, they end up everywhere; the damage they do is incalculable.

On the plus side, the broad reach of But I Heard’s pernicious influence — coupled, I suspect, with the fact that including a title page just never occurs to a lot of first-time submitters — means that if you are industry-savvy enough to include a professionally-formatted title page, your submission automatically looks like a top percentile ranker to professional eyes from the moment it’s pulled out of the envelope. It’s never too early to make a good first impression, right?

If you do not know how to format a proper title page — and yes, Virginia, there is a special format for it, too — please see the aptly-named HOW TO FORMAT TITLE PAGE category on the archive list at right. Or wait a few days until I cover it later in this series.

It’s entirely up to you. No pressure here. Have a gumball while you wait.

Before anyone who currently has a submission languishing at an agency begins to panic: you’re almost certainly not going to get rejected solely for forgetting to include a title page. It’s too common a gaffe to be an automatic deal-breaker for most Millicents. Ditto with improperly-formatted ones. And yes, one does occasionally run into an agent at a conference or one blogging online who says she doesn’t care one way or the other about whether a submission has a title page resting on top at all.

Bully for them for being so open-minded, but as I have pointed out to relative strangers roughly 147,329 times in the past year, how can you be sure that the person deciding whether to pass your submission upstairs or reject it isn’t a stickler for professionalism?

I sense some shoulders sagging at the very notion of all the work it’s going to be to alter your pages before you send them out. Please believe me when I tell you that, as tedious as it is to change these things in your manuscript now, by the time you’re on your third or fourth book, it will be second nature to you. Why, I’ll bet that the next time you sit down to begin a new writing project, you will automatically format it correctly.

Think of all of the time that will save you down the line. Goody, goody gumdrops.

More guidelines follow in the next couple of posts — yes, those of you whose hearts just sank audibly, standard format does indeed have that many rules — and then we shall move on swiftly to concrete examples of what all of this formatting looks like in practice. I want you to have enough information on the subject to be able to understand why following them might be a good idea.

Rather than, say, walking away with the vague feeling that you heard about these rules somewhere. Keep up the good work!

YA has its own distinctive conventions, particularly with respect to voice and subject matter. If it is not apparent from the first paragraph of page 1 that a manuscript is YA, even the best-written YA manuscript runs the risk of rejection on that ground alone.

YA has its own distinctive conventions, particularly with respect to voice and subject matter. If it is not apparent from the first paragraph of page 1 that a manuscript is YA, even the best-written YA manuscript runs the risk of rejection on that ground alone.