After so many white and gray Seattle winter images in a row, campers, I thought everyone might be refreshed by the sight of a little green. As I like to tell the students in my writing classes, hitting the same note over and over again, even in the name of realism, can get a little old. Breaking out of the mold occasionally can be very refreshing for the reader.

Speaking of getting set in one’s ways — or, at any rate, in one’s worldview — do you remember how at the beginning of this series, I mentioned that one reason that there’s so much conflicting advice out there about how to write a winning query letter is that to the people who handle them all the time, it honestly isn’t a matter that deserves much discussion? To an experienced agency screener like our old pal, Millicent, as well as the agent for whom she works, the differential between a solid, professional-looking query and one that, well, isn’t could not be more obvious. In addition to any content problems the latter might have, it just feels wrong to a pro.

There’s an excellent reason for that: despite continual online speculation on the subject, there honestly isn’t much debate in agency circles over what constitutes a good query letter. Nor is there really a trick to writing one: you simply need to find out what information the agent of your dreams wants to see and present it simply, cleanly, and professionally. And if the agency’s posted submission guidelines are silent about special requests — or, as still remains surprisingly common, those guidelines consist entirely of a terse query with SASE — find out what the norm is for your type of writing and gear your query toward that.

Piece of cake, right?

Actually, from an agency perspective, that’s a pretty straightforward set of directives. Because there are so many sites like this that explain what to do, as well as quite a few books, many a Millicent just can’t understand why so many aspiring writers complain that the process is confusing. They enjoy an advantage the vast majority of queriers do not, you see: they have the opportunity to see hundreds upon hundreds of professional queries for book projects. The good ones — that is, the ones that stand a significant chance of garnering a request for pages — all share certain traits. So what’s the big mystery?

Yes, yes, I know that you would never be able to tell that was the prevailing attitude, judging solely from the constant barrage of competing advice floating around out there on the subject, but frankly, the overwhelming majority of that is not written by people who have practical experience of the receiving side of the querying experience, if you catch my drift. An astonishingly high percentage of it seems to be authoritative statements by people who want to help writers, but are merely passing on what they have heard. And not always originating from a credible source.

And what’s the best way to deal with competing advice, Queryfest faithful? Chant it with me now: don’t believe everything you hear or read on the Internet, no matter how authoritatively it is phrased. Consider the source before applying the rule; if you don’t know who is recommending it, check another source. Don’t assume that a single agent’s expressed preference is applicable to the entire industry; check every single agency’s guidelines before querying or submitting. And never, ever follow a template or ostensibly must-do set of guidelines unless you are positive you understand why you need to do it that way.

Believe it or not (ah, good: you’re reading even my advice with the requisite grain of salt now), following those simple five guidelines will help remove almost all confusion. The fact is, a startlingly high proportion of the advice out there is presented both anonymously and without explanation. It’s just rules, often accompanied by dire threats aimed toward those who do not follow them. And, as I have mentioned earlier in this series, most aspiring writers instinctively quail before such threats, believing — wrongly — that credible agents feverishly crawl the web, making sure that no incorrect querying advice remains posted.

Except that doesn’t happen — frankly, there’s no reason it should. People who work in agencies already know what does and doesn’t make a good query letter, after all. Why on earth should they waste their time finding out what people outside their industry believe they want?

Especially when, let’s face it, the query they have in mind contains all of the information most agencies need in order to make a determination whether its inmates will be seriously interested in requesting pages of the book in question. Just so the list from which we’ve been working throughout Queryfest will be easily accessible to folks who (shudder!) expect to learn everything they need to know about querying a book or book proposal — again, not anything else — in a single post, please sing along, those of you with the laudable patience to have worked your way all the way through this series.

A query letter must contain:

1. The book’s title

2. The book’s category, expressed in existing category terms

3. A brief statement about why you are approaching this particular agent

4. A descriptive paragraph or two, giving a compelling foretaste of the premise, plot, and/or argument of the book, ideally in a voice similar to the narrative’s.

5. An EXTREMELY brief closing paragraph thanking the agent for considering the project.

6. The writer’s contact information and a SASE, if querying by mail

That all sounds at least a little bit familiar, I hope? If not, you will find extensive explanations — with visual examples! — earlier in this series. Moving on…

Optional elements it may prove helpful to include in your query:

7. A brief marketing paragraph explaining for whom you have written this book and why this book might appeal to that demographic in a way that no other book currently on the market does. (P.S.: before you claim that it’s literally the only book on your subject matter, do some checking; unsubstantiated sweeping generalizations are often rejection triggers.)

8. A platform paragraph giving your writing credentials and/or expertise that renders you the ideal person to have written this book.

Despite this being review, I still sense some raised hands out there. Yes, those of you joining us toward the end of this series? “Okay, I can see where there’s some overlap between your list and what I’ve seen elsewhere. Since there is, why shouldn’t I just follow the templates I’ve seen posted elsewhere?”

That groan you hear rattling around the cosmos, questioners, is the cri de coeur of the conscientious: they’ve been listening to repetitions of this particular question from late entrants since this series began. Like so much of the solid, professional development advice out there for aspiring writers, what is aimed at the crowd that longs for quick answers often bounces off its intended target and hits those who have been doing their homework diligently. So while well-meaning agents tend to formulate both their agencies’ submission guidelines and statements they make at writers’ conferences at the good 90% of queriers who do not take the time to find out how agencies actually work, the frustrated tone of some of those comments strikes the professionally-oriented 10% right between their worried eyes.

Which is to say: you’ll find the answer to that issue earlier in this series, first-time questioners. Because I believe so strongly that it does a disservice to serious aspiring writers — that 10% with the crease rapidly becoming permanently etched between their thoughtful eyes — to provide only glib how-to lists, I would be the last to discourage anyone who wants to make a living writing books from learning the logic behind what Millicent expects her to do. (See earlier comment about this perhaps not being the blog for those who prefer short, simple answers to complicated questions.)

That being said, there is a short, simple answer to that particular question: because not all of the query templates out there are for books, that’s why. As I’ve mentioned before in this series, much of the query advice out there does not mention explicitly whether the query being described is for a book, a magazine article, a short story, an academic article…

Well, you get the idea, right? Contrary to popular opinion, not every entity dealing with writing carries the same expectations. Or desires the same type of query. Or expects identical formatting. Pretending that because a query designed to propose an article or short story was posted online, marked query, must necessarily be equally appropriate for a book proposal, despite the fact that the two would be read by completely different professional audiences, does not make it so.

Yet that is precisely what many of the templates out there do, frequently without telling those who stumble across them that the formula or visual approximation is geared toward a particular part of the writing industry. Because writing is writing, right?

Not to those who handle writing professionally, no — which is why, in case those of you confused (and who could blame you?) by competing querying advice had been wondering, the argument but I saw it done this way online!/in a book of advice for writers/in what a friend of a friend of a professional writer forwarded me! will cut no slack with Millicent. Why should it? In fact, why on earth would an agency that represents books and book proposals care at all what the querying norms are for any other kind of writing?

So let’s add a sixth simple rule, while we’re at it: don’t follow generic advice. If you read through querying advice carefully and still cannot tell whether it is intended to help writers of books, poets, short story writers, or those trying to break into journalism, move on to another, more specific source.

To make sure we’re all on the same page, so to speak, let me make it pellucidly clear: the advice in Queryfest is intended only to assist writers of book-length works querying agencies or small publishers within the United States. It is aimed at helping aspiring writers produce a solid query that will look and feel right to that specific group of readers. I make every attempt never to ask my readers to follow a rule without explaining it, and I encourage all of you to ask questions if anything remains unclear. (Do take the time to read the relevant post first, though, huh? Every advice-giving writing blogger I know positively hates it when commenters ask for a recap of questions already answered in that post.) As always, though, I would urge any writer following this advice to double-check any submission guidelines a particular agency might have taken the time to post or list in one of the standard agency guides.

Everybody okay with that? If not, may I suggest that Queryfest may not be for you, and wish you luck finding the answers you seek elsewhere?

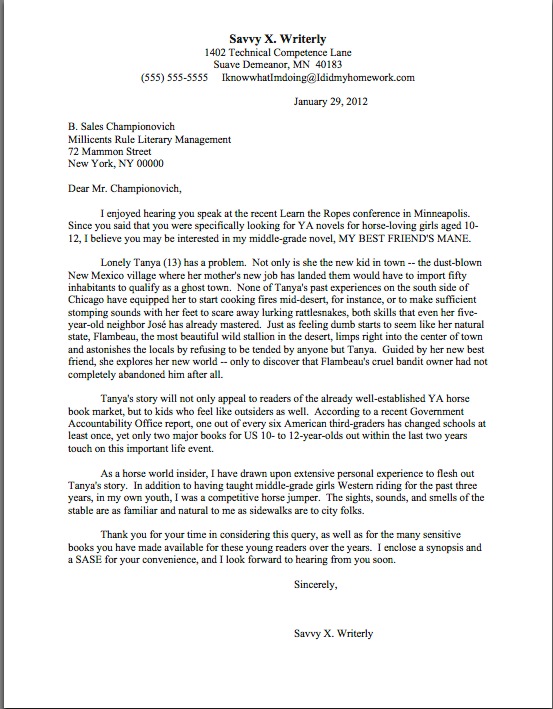

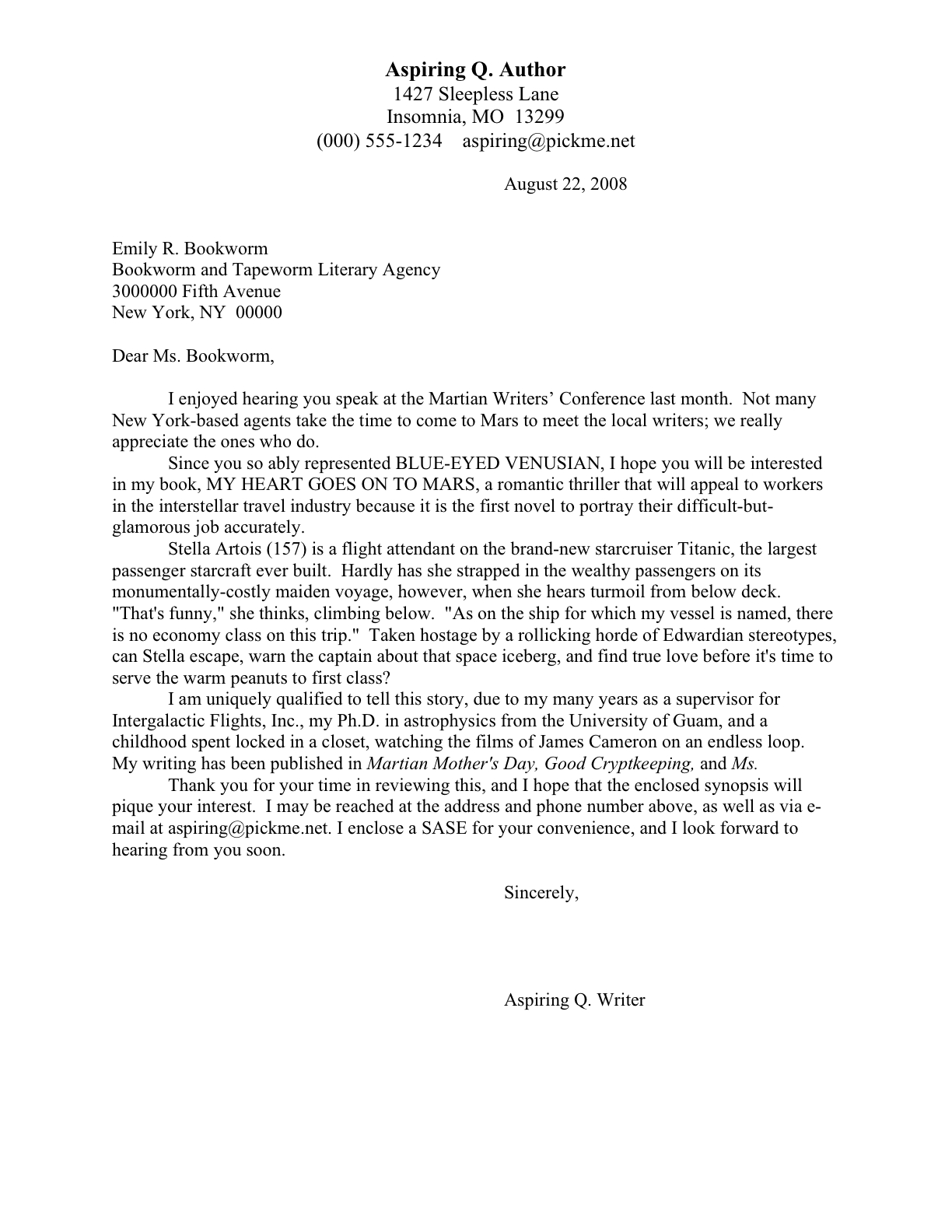

The same train of logic applies, I tremble to tell you, to how a query is presented on a page. And that’s unfortunate for many queriers, for although neither the requirement that a query be limited to a single page nor the rules for correspondence format have actually not changed at all since the advent of the word processor — it’s merely easier to center things in Word than on a typewriter — fewer typing classes in schools have inevitably led to a lower percentage of the population’s being familiar with how a formal letter should look on a page. Which is, should anyone be wondering, like this:

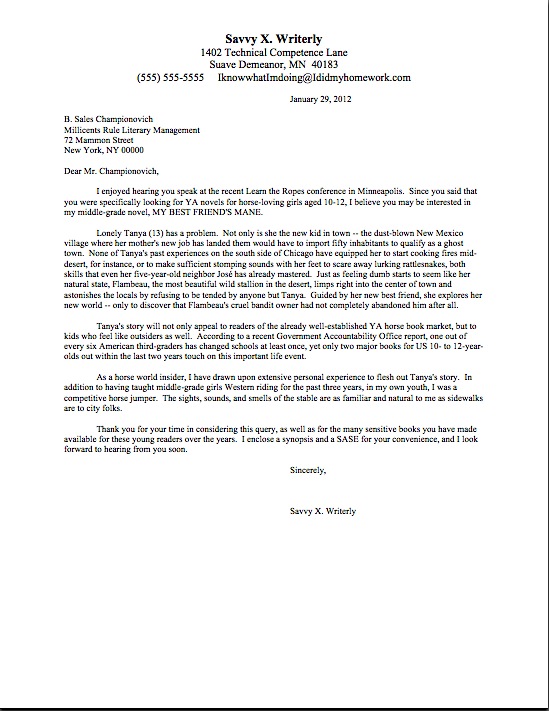

Or like this:

Either will look right to Millicent, either in a paper query or via e-mail; for reasons I have explained at great length and with abundant visual examples earlier in this series, at a traditional agency, these are the only acceptable query formats. (Yes, yes: younger agents, ones who went through school after typing classes became rare, are less likely to care deeply, but business format has for so long been despised in the publishing industry as only semi-literate that it honestly isn’t prudent to use it in a paper query.)

Judging by the hundreds of queries I’m asked to evaluate every year (I’m currently running a limited-time special on it, should anyone be interested), correspondence format does not seem to be familiar to many aspiring writers, at least not in its typed form. So let’s pause for a moment to go over what will strike Millicent as right about both the letters above, shall we?

A paper query in correspondence format should feature, from top to bottom:

1. Single-spacing, with 1-inch margins on each side. The only acceptable exception to the latter is

2. The sender’s contact information, either centered in the header or appearing directly under the signature, never both. If you choose to use the centered at the top option, you may use boldface or a slightly larger font for this information. Otherwise,

3. Everything in the letter should be in the same font and size. For a query, the industry standard is 12-point Times New Roman or Courier. (More on the importance of that below.)

4. The date of writing, tabbed to halfway or just over halfway across the first line of text. In Word, that’s either 3.5″ or 4″.

5. The recipient’s full address. That one is borrowed from business format, actually, but it’s a prudent theft: it maximizes the probability that your missive will end up on the right desk.

6. A salutation in the form of Dear Ms. Smith or Dear Mr. Jones, followed by either a colon or a comma. Stick to one or the other, in both cases. In the U.S., unless you know for a fact that the recipient either (a) holds an earned doctorate, like your humble correspondent, (b) is an ordained minister, or (c) is a married woman who actively prefers being called Mrs., the only polite option for a female recipient is Ms. And no matter how gender-ambiguous an agent’s first name may be of the recipient’s sex, never address a query to Dear Chris Brown; check the agency’s website or call the agency to ask.

7. In the body of the letter, all paragraphs should be indented. No exceptions. In Word, the customary paragraph indention tab — which is to say, the one that’s expected in a manuscript, as well as a letter — is .5″. If you like and space permits, you may skip a line between paragraphs, for readability, but it is not mandatory.

8. In a query, titles of books may appear either in ALL CAPS or in italics. Choose one and be consistent throughout the letter; it drives a detail-oriented soul like Millicent nuts to see both on the same page. If you cite a magazine or newspaper in your query, its name should appear in italics.

9. A polite sign-off, tabbed to the same point on the page as the date. No need to be fancy; sincerely will do.

10. Three or four skipped lines for your actual signature.

11. Your name, printed, tabbed to the same point on the page as the sign-off, with your contact information below, if it has not appeared at the top of the page.

Those are the rules that would apply to any letter in correspondence format. For a paper query, observing other guidelines are also advisable.

12. A query should be printed in black ink on white paper. While it’s not mandatory to print your query on bright white paper, 20-lb. weight or better (I always advise my clients to use 24-lb; it won’t wilt with repeated readings), black ink shows up best upon it.

13. I mean it about the white paper: no exceptions. No matter how tempting it is to believe that your query will stand out more if you print it on, say, buff, gray, or ecru, it’s not a good idea. Yes, it will not look like the others, but this is a business that prides itself on uniformity of presentation. Don’t risk it.

14. A query should never exceed a single page. Again, no exceptions.

15. Sorry, queriers-from-afar, but if you plan on sending a paper query to a US-based agency, their Millicents will expect it to be printed on locally-standard 8.5″ x 11″ paper, not A4. On the bright side, they’ll expect your manuscript to be printed on that US paper, too, so you might as well stock up on it.

If you have trouble tracking down that size outside North America, try asking at your local FedEx (it ate Kinko’s, whose foreign branches almost always carried at least a few reams of our-sized paper, for the benefit of traveling business folk) or a hotel that caters to business travelers. You could also just go for broke and order a few reams of paper online from a US-based company — or an American-owned one like Amazon UK. Because I love you people, I’ve just checked the latter, and I found the proper size at a fairly reasonable price.

If you are querying via e-mail, of course, you should skip a few of these niceties: because it is difficult to ensure that spacing will remain intact in transit (it’s strange how much a different e-mail program can mangle an otherwise perfectly acceptable letter, isn’t it?), it’s safer not to skip lines between paragraphs. While indentation is still nice, it isn’t mandatory here, and as e-mails inherently contain a date marker, you need not include the date line. For the same reason, you may omit the recipient’s full address, beginning the e-mail instead with the salutation. Contact information belongs at the bottom of the letter, and most e-mailed correspondence features a left-justified sign-off and signature.

Having a bit of trouble picturing those differences? Here’s that letter again, as it would appear in an e-mail.

Looks quite different, does it not? That’s purely a matter of necessity, not of industry-wide preference: since many e-mail programs force users to opt for business format (no indentation, a skipped line between paragraphs, date, sign-off, and signature all lined up with the left margin), Millicent has, like her bosses, reluctantly come to accept non-indented paragraphs. But that doesn’t mean the purists in the industry like it as a trend.

They saw the slippery slope from a mile away, you see: because both the Internet and e-mail programs disproportionately favor (ugh) lack of indentation, an ever-increasing segment of the otherwise literate population has come to regard that format as (double ugh) perfectly proper. So although I wince even to bring it up, Millicent has also been seeing more and more actual manuscript submissions devoid of indentation, instead skipping lines between paragraphs.

Which is, incidentally, not the right way to format a book manuscript or proposal, as I devoutly hope those who read my Formatpalooza post on the subject already know. (And if any of that’s news to you, please run, don’t walk, to the HOW TO FORMAT A BOOK MANUSCRIPT category on the archive list at right.) In fact, business format so different from how agency denizens expect text to appear on a page intended for submission to a publishing house that Millicent typically won’t even begin to read it.

Why, those of you who write that way habitually scream in terror? Well, can you think of a better way for her to tell at a glance whether the submitter has taken the time to learn how book manuscripts and proposals are submitted to publishing houses? It’s not as though an agent could possibly submit an unindented manuscript to an editor, after all.

Was that resonant thunk I just heard the sound of thousands of writerly jaws hitting floors, or do I need to explain the direct implication for queries? “But Anne,” many of you moan, clutching your sore mandibles, “now that I see correspondence format in action, I realize that I have been borrowing elements from across a couple of styles for my regular mail queries. If I may borrow your last example for a moment to show you what I’ve been doing, can you tell me how Millicent might respond to it? And should I be sitting down before you answer?”

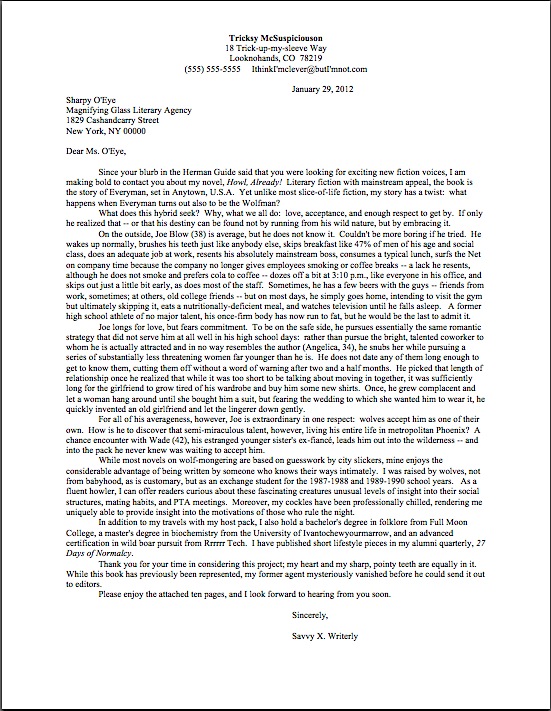

Of course, jaw-clutchers — and yes, a chair might be a good idea. Perhaps even a fainting couch, because I suspect what you have on your hands is a good, old-fashioned Frankenstein query.

Comfy? Okay, let’s take a gander — and to render this better practice, try slipping into Millicent’s spectacles for the duration. If you were she, what would strike you as incongruous, and thus distracting from the actual content of the letter?

Quite a contrast with what our Millie was expecting to see, isn’t it? Let’s start at the top of this discolored page — would you have read that, in Millicent’s desk chair? — and work our way down. First, in a charmingly archaic but misguided attempt to mimic casual letterhead (traditionally reserved for handwritten notes, by the way), the Frankenstein querier has chosen a truly wacky typeface to showcase his contact information. Doesn’t look very professional on the page, does it?

From there, the mish-mosh of styles becomes less visually distracting, but comes across as no less confused. While the left-justified date, lack of indentation in the body of the letter, and skipped lines between paragraph would lead anyone who began reading, as those zany screeners like to do, at the beginning of the letter and proceeding downward to presume that the letter is in business format, the sign-off and the signature are not in the right place for that format. Nor are they in the right place for correspondence format: they are too far right. Muddling things still further, the RE: line is appropriate for a memo, not a letter.

In the face of all that visual inconsistency, I wouldn’t blame you if you missed some of the subtler missteps, but I assure you, a well-trained Millicent wouldn’t. The missing comma in the date, for instance, or the fact that while one book title is presented in all capital letters, the other is in italics, for no conceivable reason. (Unless our querier is laboring under the false impression that published books’ titles should appear one way, and unpublished manuscripts another? Agencies typically make no such distinction.) Then, too, the oddball subject line appears in boldface, as well as The Washington Post. Again, why?

So while this query does indeed stand out from the crowd — doubtless the intent behind that horrendous yellow paper — it doesn’t leap from the stack for the right reasons. And what does it gain by the effort? By eschewing a more traditional presentation, all it really achieves is buying a little extra time for Millicent: this is not, apparently, a query she needs to take particularly seriously.

Shocked? Don’t be. Just as Millicent and her cronies have a sense of what information does and does not belong in a query, over time, as they process thousands of queries, she begins to gain the ability to tell at a glance which queries simply don’t have a chance of succeeding at her agency. The ones that don’t mention a book category, for instance, or those that present a book or proposal in a category her boss does not represent. The ones with typos, or the ones that are one long book description. The ones filled with typos. And — brace yourself — the ones that are formatted as though (and this is Millicent talking here, not me) the writer had never seen a letter before.

Oh, that last one isn’t always an automatic-rejection offense, but inevitably, odd formatting affects a pro’s perception of a writer’s professionalism. How? Well, just as agents and editors develop an almost visceral sense of whether a manuscript is in standard format or not, their screeners learn pretty fast what a good query looks like. And just as they often will automatically begin reading an unprofessionally-formatted submission with an expectation that the writing will not be as polished as that in a manuscript that looks right, Millicents frequently will read an oddly-presented query with a slightly jaundiced eye.

Especially, as it happens, if the query in question appears specifically designed to generate unnecessary eye strain. To someone who reads all day, every day, the difference between a query in the publishing industry’s standard, 12-point Times New Roman or Courier:

and precisely the same query in 10-point type:

could not possibly be greater, unless the latter were printed on that bizarre yellow paper from our previous example. The first utilizes the font size in which Millicent expects to see all manuscripts, book proposals, queries, synopses, and anything else its denizens ask to see; the second, well, isn’t. But that’s not the kind of thing an agent is likely to blurt out at a conference, mention on his blog, or even — you might want brace to yourself, if you’re new to the game — list as a required query attribute in the submission guidelines on his agency’s website.

Why, those of you surveying the difference for the first time ask in horror? Because 12-point is used universally for book manuscripts and proposals (in the U.S., at least), it would never occur to anyone who screens for a living that any other size of type was acceptable. Anything else simply looks wrong on the page.

To be blunt about it, most Millicents — heck, most professional readers — would consider the second example above not only strange; she’s also likely to regard it as rude. After all, from her perspective, all the smaller type means is greater eyestrain for her: clearly, the writer of the second version hadn’t considered that there might be a human being with tired eyes on the receiving end of that missive.

Seriously, if you were Millicent, how would you respond if a query with minuscule type appeared on your desk? Would you invest the extra minute or two in trying to make out what it says, or would you just move on?

For most Millicents, there’s just no contest: move on, and swiftly, just as she would if the query in question were a badly-smudged photocopy. Given that it’s her job to narrow the field of queries down to the 5% or less that her boss might conceivably have time to consider, why would she bother to give more than a passing glance to a missive that simply screams, “The person who wrote this is either unaware that manuscripts are supposed to be in 12-point type, or just doesn’t care how difficult he is making your life, screener!”

And yes, before anyone asks, she is equally likely to reach that unflattering conclusion regardless of whether Millicent is reading that query on a printed page or on a computer screen. Just because our Millie can increase the size of the e-mail in front of her does not mean that she will take — or even have — the time to do it, after all.

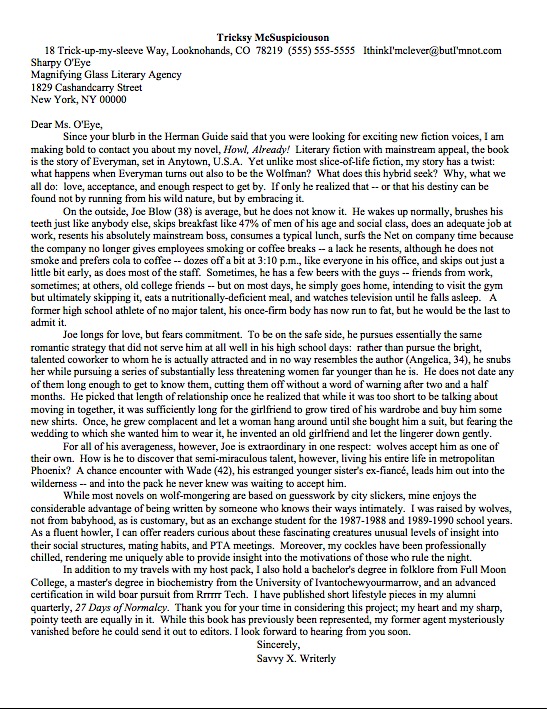

Especially when — again, you might want to brace yourself, neophytes — the single most logical explanation for why a querier would select the smaller type size would to be to commit the following instant-rejection offense; see if you can catch it. As always, if you are having difficulty reading individual words, try holding down the COMMAND key and pressing + to enlarge the image; just because Millicent doesn’t have the time to avoid eyestrain in this manner doesn’t mean you should tire out your peepers.

Awfully hard to read, isn’t it? Any guesses about why this version would set off rejection red flags, even if Millicent happened to be unusually fresh-eyed and in a good enough mood to try to make it out?

To someone as familiar with the standard one-page query as she, it would be perfectly plain that were these words in ordinary-sized type, this letter would be longer than the requisite single page. Which, as I hope we all already know, would automatically have resulted in rejection, even had Tricksy been honest enough to use a 12-point font.

And yes, in response to what half of you who favor e-querying just thought very loudly indeed, Millicent probably would also have caught the extra length had this query been sent via e-mail, where page length is less obvious. But whether Tricksy decided to avoid the necessity of trimming by typeface games or by just hoping no one would notice an extra few lines, trust me, she’s not likely to pull the wool over an experienced query reader like Millicent. Fudging is fudging, regardless of how it is done.

Remember, the one-page limit is not arbitrary, a mere hoop through which aspiring writers are expected to jump purely so Millicent can enjoy the spectacle; queries are also that short so she can get through even a quarter of the missives that arrive in a day at an even marginally established agency. It’s also, let’s face it, the first chance the agency has to see if a potential client can follow directions.

You would be flabbergasted at how many queries just bellow between their ill-formatted lines, “Hey, Millie, this one didn’t read the agency’s submission guidelines!” or “Hey, you’re going to have to explain things twice to this writer!” Or even, sadly, “Wow, this querier either has no idea what he is doing — or he is actively trying to circumvent the rules!” Is that really how you want the agent of your dreams (and her staff) to think of you as a writer?

Perhaps it is a bit counterintuitive, but to many Millicents, obvious attempts to cheat — yes, that’s how they tend to think of creative means of reformatting a too-long query so it will fit on the page — are every bit as off-putting as missing elements. Had querier Tricksy altered the margins, removed the date, and/or compressed the contact information in order to achieve the illusion of shortness, the result would probably have been instant rejection. Let’s nip any tendencies in that direction in the bud by showing just how ridiculous the hope that Millie wouldn’t notice this actually is.

Doesn’t stand a chance of passing as normal, does it? The sad thing is, had Tricksy put half as much effort into fine-tuning this query as she did trying to fool Millicent with fancy formatting tricks, she probably could have trimmed it to an acceptable length. As it stands, her formatting gymnastics are just too distracting from the letter’s content to be anything but a liability.

The moral of all this, should you be curious, is fourfold. First, rather than wasting time and energy resenting having to learn what Millicent and her ilk expect to see, or complaining that the pros have not, do not, and have no future intention of sifting through all of the competing querying advice out there — why should they, when they already know the rules? — why not invest that time and energy in researching what precisely it is the individual agents who interest you actually do want? That’s far more likely to bear fruit than searching for a single, foolproof, one-size fits all template to fit all of your querying needs. And no matter how much queriers would like it not to be the case, there’s just no substitute for checking every agency’s guidelines, every time.

Second, when you do that research, consider the source of information: is it credible, and is it specifically aimed at writers of your kind of work? If, after reading through the offerings, you can’t comfortably answer both of those questions, start looking for more information and asking for clarification. Before you take even the most authoritative-sounding advice — yes, even mine — it’s in your interest to make absolutely certain you understand precisely what you are being advised to do, and why.

Which brings me to the third moral: as nice as it would be if every agency currently accepting new clients posted a step-by-step guide to writing precisely the query letter it wants to see, the overwhelming majority of US-based agencies do not get very specific about it. Even those that do list requirements often leave them rather vague: give us some indication of who would want to read this book and why or tell us about your platform is about as prescriptive as they ever get.

And, let’s face it, when many writers new to the game read such requests, they feel as though they are being told that no one will ever want to read their books unless they somehow manage to become celebrities first. Which, for someone who was planning to attain celebrity by writing a terrific book, that impression can be terribly off-putting.

It should cheer you to know, however, that such statements are only rarely intended to scare newbies away. Indeed, agents often truly believe those admonitions to be helpful; remember, those directives are typically aimed at preventing the faux pas commonly made by the 90% of queriers who don’t do their research, not the 10% that do. And if submission guidelines tend to be a bit on the nebulous side, it’s just that to people who read queries and submissions for a living, sheer repetition has made the basic structure of a solid query seem to be self-evident. They’d no more think of explaining the difference between an unsuccessful descriptive paragraph and one that sings than they would undertake to explain to you how to walk. No one is born knowing how to do it, of course, but once a person has learned the mechanics, it becomes second nature.

Just how obvious do the elements of the query appear to the pros, you ask? Well, at the risk of seeming myopic, until this afternoon, it hadn’t occurred to me that any of you fine people might actually want a category on the archive list entitled HOW TO FORMAT A QUERY LETTER. After all, I had discussed formatting early in Queryfest; throughout the course of this series, I’ve posted dozens of visual examples. Yet when a reader asked me about it this afternoon, I was stunned to realize that I’d never done a post like this, one that listed all the requisite elements and the formatting requirements in one place.

I grew up surrounded by agented writers, you see; I actually can’t remember a time when I didn’t know what a properly-formatted query looked like. Or a properly-formatted manuscript, for that matter. Or that other kinds of writing called for different iterations of both.

Which leads me to the fourth and final moral of the evening: even the best-intentioned and most credible query advice-givers, the ones with actual professional experience to back up their opinions — who are, as we have discussed, usually in the minority online — may not always be able to second-guess what a writer brand-new to the game wants to know. Or even what he needs to know, because advice-dispensers like me are not always aware of what advice-takers don’t know.

Could you explain the pure mechanics of walking? Or of snapping your fingers? No, you probably just do both. That unthinking fluency is a product of practice, of long experience.

If you want to benefit from someone else’s experience, though — and isn’t that what seeking out advice is all about? — don’t expect the advisor either to read your mind or to tell you spontaneously what you want to know. Oh, I try; quite a few of us do. I hear from writers all the time who have landed agents following the advice I’ve posted here, and without ever having posted a question in the comments. But I can do a better job teaching you the ropes if you ask questions.

I don’t know what all of you do and don’t know, you see. It’s just a different perspective.

So as we wend our way through the last few Queryfest posts and back toward the more creatively-exciting pastures of craft and self-editing, I would strongly encourage you to post questions in the comments. Actually, I welcome questions all the time, but I’m especially interested in knowing if anything about the querying process remains fuzzy to those of you who have been following this series. I shall also, while we’re finishing up our examination of readers’ queries, be trotting out some well-founded readers’ questions that I’ve been intending to address at length for quite some time.

Many thanks to the reader who asked me for this post, and everybody, keep up the good work!