While lazily re-reading the letters of Madame de Sévigné, as one so often does at this time of year, I stumbled across a particularly revealing review of a book released several centuries ago. Quoth the great lady:

This Morale of Nicole is admirable, and Cléopatre is going along nicely, but in no hurry; it is for odd moments. Usually, it is reading this that lulls me to sleep — the large print pleases me much more than the style.

That prompted me to cast a hurried eye at the calendar, as you may imagine. “Good gravy!” I exclaimed. “Aspiring writers across this great nation are about to be having Thanksgiving dinner with otherwise charming relatives and friends who wouldn’t know literature if it were floating in the cranberry sauce! It’s time to trot out my annual balm for the souls of writers passing the mashed potatoes while trying to answer well-meant questions like ‘So you’re a writer? What have you published?’ and ‘What — you’re still working on that novel after all this time?’ Not to mention the ever-popular ‘Oh, you’re writing these days? I’d just assumed you’d given up on that dream.’”

And writers throughout the land groan with recognition. There, there, campers — you didn’t think I was going to send you over the river and through the woods without a few words of encouragement, did you?

Yet already, the eyebrows of those new to treading the path literary shoot skyward. “But Anne,” bright-eyed neophytes everywhere murmur, “aren’t you borrowing trouble here? Everyone loves a dreamer, and everyone adores good writing; therefore, it follows as night the day that everyone must be just wild about a good writer’s pursuing the dream of publication. So what makes you think we need a pep talk prior to venturing into the no doubt warm and accepting bosoms of our respective families and/or dining rooms of our inevitably supportive friends?”

Experience, mostly. In descending order of probability, a writing blogger, a fellow writer, and an editor provide the three most likely shoulders aspiring writers will dampen with their frustrated tears immediately after the festive eating and good fellowship cease. Heck, this time of year, even relatively well-established authors often beard the heavens with their bootless cries.

“Why,” they demand of the unhearing muses and anybody else who will listen, “can’t Aunt Myra, bless her heart, stop asking me why she regularly sees worse books than yours on the bestseller lists? Why must Cousin Reginald tell me at such length about his co-worker’s experience with self-publishing, as if that were relevant to my more traditional path? And why oh why cannot my beloved fraternal quadruplet Cristobal refrain from accusing me of being lazy because the memoir I wrote six years ago wasn’t out last June as a beach read?”

Excellent questions, all, but ones that can be addressed with a single answer: most non-writers harbor completely unrealistic notions about how and why good books get published. They believe, you see, in the Publishing Fairy, that completely fictional entity assigned by a beneficent universe to carry manuscripts directly from first conception to published volume swiftly, easily, and with no effort required from the writer.

Apart from the sheer act of sitting down and writing the darned thing, of course. But Aunt Myra has always suspected that half the time you claim to be spending sitting in front of your computer, wrestling with the muses, you’re actually on Facebook.

I pity Aunt Myra, Cousin Reginald, and your former womb mate Cristobal, though, truly. As a direct result of their implicit belief in the Publication Fairy and her seldom-seen-in-practice ways, they feel compelled to regard the absolutely normal years their beloved writer has spent struggling to learn the craft, wrenching the soul into written form, finding an agent who resonates with a genuinely original voice and vision, alternately waiting and revising while said agent shops the manuscript to publishers, subsequent waiting and revising while the book is in press, and exhausting marketing process as, well, abnormal.

And that, in case you had been shaking your head in wonder over a turkey leg, is why so many honest-to-goodness nice folks who deeply care about you can sound so incredibly awful when they feel forced to inquire about your writing. All of those fears about why the Publication Fairy has passed you by — or, at the very least, hasn’t yet taken you by the hand and led you to Oprah, The Colbert Report, or The New York Times Review of Books, tend to be compressed conversationally at every stage into the same ilk of question: “Why isn’t your book published yet?” They’re trying, in short, to be kind.

That’s not always apparent in the minute, though, is it? And if you’re like the overwhelming majority of writers, you’ve probably tumbled at least once into the bear trap of assuming that it was your fault for talking about your writing at all.

Come on, admit it — you’ve wished in retrospect that you hadn’t brought up your book. How could you not, when, in the course of your detailed account of just how many inches you have gnawed off your fingernails while waiting for that agent who asked for an exclusive to get back to you — it’s been five months! — Grandmamma plucked your sleeve and murmured tenderly, “Honey, why isn’t your novel in the stores? I keep telling my friends that you write” over the pie course? Didn’t you struggle just a bit to come up with a different answer than you had given her the last four times she’d asked?

If it’s any comfort, that bear trap lurks in the shadows later in the publishing process as well. When you’re six days from a hard deadline to get a revision you think is a bad idea to your publisher, Uncle Clark may well chortle, “Memoir? What on earth do you have to write memoirs about? You’re not the president.” Bearing in mind that he is fully capable of saying this to you after you have been elected president provides scant comfort, I’m sorry to say.

Or, when you’re over the moon because an agent — a real, live, honest-to-goodness agent! — has agreed to represent your baby, Gertrude-who-doesn’t-have-any-family-locally will boom over her second helping of glazed carrots, “Oh, congratulations! When’s the book coming out?” Invariably, while you are struggling to explain the vital difference between signing a representation contract and a contract with a publisher, the relative responsible for inviting Gertrude will attempt to change the subject. Perhaps violently.

And every writer currently treading the earth’s crust has encountered some form of Cousin Antoinette’s why-isn’t-he-her-ex-husband-yet’s annual passive-aggressive attempt at hearty encouragement. “Still no agent, eh? I’d always thought that the really good books got snapped up right away. Have you thought at all about self-publishing? A good writer can make a lot of money that way, right?”

Am I correct that you have on occasion kicked yourself for your reaction — or non-reaction — to such outrageous stimuli? I’m sure you’ve told yourself that a sane, confident, unusually secure writer might well have answered: “Why, yes, Roger, I have indeed thought about self-publishing. As I had last year and the year before, when you had previously proffered this self-evident suggestion. Now shut up, please, and pass the darned yams.”

Or piped merrily, “Well, as the agents like to say, Uncle Clark, it all depends on the writing. So unless you’d like me to embark upon a fifty-two minute explanation of the intrinsic differences between the Ulysses S. Grant-style national-scale autobiography that you probably have in mind and a personal memoir about the adolescence in which you played a minor but memorably disagreeable role — a disquisition with which I would be all too happy to bore the entire table — could I interest you in a third helping of these delightful vermouth-doused string beans?”

Or chirped between courses, “You know, Gertie, that’s a common misconception. If you’d like to learn something about how the publication process actually works, I could refer you to an excellent blog.”

Or, while Grandmamma’s mouth is full of pie, observed suavely, “I so appreciate your drumming up future readers for my novel, dearest; I’m sure that will come in very handy down the road. But no, ‘trying just a little harder this year’ won’t necessarily make the difference between hitting the bestseller lists and obscurity. You might want to try telling your friends that even if I landed an agent for my novel within the next few days — even less likely at this time of year than others, by the way, as the publishing world slows to a crawl between Thanksgiving and the end of the year — it could easily be a year or two before you can realistically urge them to buy my novel. Thanks for your reliable support, though; it means a lot to me.”

Most of us aren’t up to that level of even-tempered and informative riposte, alas. We’re more inclined to get defensive, to tell Dad he doesn’t know whereat he speaks — or to stuff our traitorous mouths with mashed potatoes so we won’t tell Dad he doesn’t know whereat he speaks. In the moment, even the best-intentioned of those questions can sound very much like an insidious echo of that self-doubting hobgoblin that so loves to lurk in the back of the creative mind.

“If you were truly talented,” that little beastie loves to murmur in the ear of a writer already feeling discouraged, “an admiring public would already be enjoying your work in droves. And in paperback. Now stop thinking about your book and go score more leftover pie and some coffee; tormenting you is thirsty work.”

Admit it — you’re on a first-name basis with that goblin. It’s been whispering in your ear ever since you began to query. Or submit. Or perhaps as soon as you started to write.

Even so, you’re entitled to be a little startled when Bertie with the pitchfork suddenly begins speaking out of the mouth of that otherwise perfectly pleasant person your brother brought along to dinner because he’s new to town and has nowhere else to go on Thanksgiving. Instead of emptying that conveniently nearby vat of cranberry sauce over his Adonis-like curls, may I suggest trying to be charitable? Your brother’s friend may actually be doing you a favor by verbalizing your lingering doubts, you know.

“Wait — how?” you ask, cranberry-filled vat already aloft.

Well, it’s a heck of a lot easier to argue with a living, breathing person than someone whose base camp is located inside your head. Astonishingly often, an artless question like “Oh, you write? Would I have read any of your work?” from the ignoramus across the table will give voice to a niggling doubt that’s been eating at a talented writer for years.

Or so I surmise, from how frequently writers complain about such questions. “How insensitive can they be?” writers inevitably wail in the wake of holiday gatherings, and who could blame them? “I swear that I heard ‘So when is your book coming out?’ twice as often as ‘Pass the gravy, please.’ Why is it that my kith/kin/the kith and/or kin of some acquaintance kind enough to feed me don’t seem to have the faintest idea of what it means to be a working writer, as opposed to the fantasy kind that writes a book one minute, is instantly and spontaneously solicited by an agent the next, and is chatting on a couch with a late-night TV host immediately thereafter? Why is publication — and wildly successful publication at that — so frequently regarded as the only measure of writing talent?”

The short answer to that extraordinarily well-justified cri de coeur is an unfortunately cruel one: because that’s how society at large judges writing. I’m relatively certain, though, that the question-asking gravy-eschewers who drove the writers mentioned above to distraction (and, quite possibly, drove them home afterward) did not intend to be cruel. They’re just echoing a common misunderstanding of how books do and don’t get published.

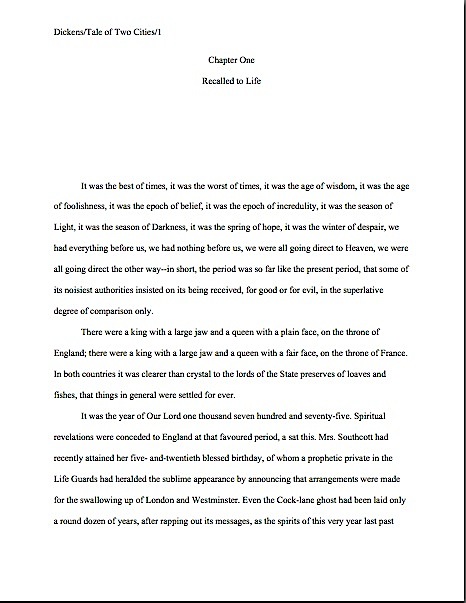

Which brings us once again to our old pal, the Publication Fairy. Her pixie dust can blind even the most sensible bystander to the writing process. Not only does popular belief hold that the only good book is a published book — a proposition that would make anyone who actually handles manuscripts for a living positively gasp with laughter — but also that if a writer were actually gifted, publication would be both swift and inevitable, following with little or no effort hard upon typing THE END on a first draft. Commercial success arrives invariably for great books, too, because unless the author happens to be a celebrity in another field, the only possible difference between a book that lands the author on the bestseller lists and one that languishes unpurchased on a shelf is the quality of the writing, right? Because no one ever buys a book without reading it first.

Are you guffawing yet? More importantly, is Bertie the Hobgoblin? Trust me, anyone who works with manuscripts for a living would be rolling on the shag carpet by now.

Yet I sense that you’re not laughing. You’re not even smiling. In fact, if you’re honest about it, you and Bertie may have been nodding silently while reading through that list of risible untruths about publishing.

Because this is such a frequent source of self-doubt, let’s tease out the logic a little. If we accept all of the suppositions as accurate, there are only two conceivable reasons that a manuscript could possibly not already be published: it’s not yet completed (in which case the writer is lazy, right?) or it simply isn’t any good (and thus does not deserve to be published). That means, invariably, that a writer complaining about how hard the road is must either need a kick in the rump or gentle dissuasion from pursuing a dream that can’t possibly come true.

Fortunately for dinner-table harmony, most nice folks aren’t up to providing either to a relative they see only once or twice a year. (Although your Aunt Gloria is always up for a little rump-kicking, I hear.) Accordingly, they figure, the only generous response to a writer who has been at it a while, yet does not have a book out, must be to avert one’s eyes and make vaguely encouraging noises.

Or to change the subject altogether. Really, it isn’t your sister’s coworker’s fault that your mother told him to sit next to the writer in the family. Why, the coworker thinks, rub salt in the already-wounded ego of some poor soul writhing under a first query rejection, and who therefore clearly has no talent for writing?

Chuckling yet? You should be. While it is of course conceivable that any of the reasons above could be stifling the publication chances of any particular manuscript to which a hopeful writer might refer after a relative she sees only once a year claps her heartily on the back and bellows, “How’s the writing coming, Violet?” yet again, the very notion that writing success should be measured — or could be adequately measured — solely by whether the mythical Publication Fairy has yet whacked it with her Print-and-Bind-It-Now wand would cause the pros to choke with mirth.

So would the length of that last sentence, come to think of it. Ol’ Henry James must surely be beaming down at me from the literary heavens over that one. Unless he’s still lingering over the pecan pie with Madame de Sévigné, Noël Coward, and Euripides. (They’re always the last to leave the table.)

Again, though, my finely-tuned antennae tell me that some of you are not in fact choking with mirth. “But Anne,” frustrated writers everywhere point out, “although naturally, I know from reading this blog (particularly the informative posts under the HOW THE PUBLISHING INDUSTRY WORKS — AND DOESN’T category at right), listening carefully to what agents say they want, and observation of the career trajectories of both my writer friends and established authors alike, that many an excellent manuscript languishes for years without being picked up, part of me really, really, REALLY wants to believe that’s not actually the case. Or at least that it will not be in my case.”

See what I mean about the holidays’ capacity for causing those internalized pernicious assumptions to leap out of the mind and demand to be fed? Let’s listen for a bit longer; perhaps we can learn something more. Let’s get it all out on the table.

“If the literary universe is fair,” writers and their pet hobgoblins typically reason…

(Stop here for every agent, editor, and book promoter who has ever lived to snort with hilarity.)

“…a good manuscript should always find a home. If that’s true, perhaps my kith and kin are right that if I were really talented, the only thing I would ever have to say at Thanksgiving is that my book is already out and where I would like them to buy it.”

Actually, in that instance, you would be fending off injured cries of “Where is my free copy?” But we’ll talk about that later. Your hobgoblins were saying?

“Since it’s an agent’s job to find exciting new talent,” Bernie et al. continue, “and my query — not my manuscript — has been rejected by four agents and I’ve never heard back from the fifth who asked to see the first 30 pages, there’s really no point in continuing to try to find an agent for this book. They all share the same tastes, and anyway, they’d probably only want me to change things in my manuscript. Maybe Roger is right to urge me to self-publish. But then all of the costs and pressures of promotion would fall on me, and…”

“Wait just a book-signing minute!” another group of not-yet-completely-frustrated writers and their hobgoblins interrupt us. “What do you mean, many an excellent manuscript languishes for years without being picked up? How is that possible? Isn’t it the publishing industry’s job — and its sole job — to identify and promote writing talent? And doesn’t that mean that any truly talented writer will be so identified and promoted, if only he is brave enough to send out work persistently, until he finds the right agent for it?”

“Whoa!” still a third demographic and its internal demons shout en masse. “Send out work persistently? Rejected by four agents — and not heard back from a fifth? I thought that if a writer was genuinely gifted, any good agent would snatch up her manuscript. So why would any excellent writer need to query more than one or two times?”

Do you hear yourselves, people? You’re invoking the Publishing Fairy. Are you absolutely certain you want to do that?

It’s a dangerous practice for a writer, you know. The Publication Fairy’s long, shallow shadow can render seeing one’s own publication chances decrease over time. Following her siren song can lead a writer to believe, for instance, that the goal of querying is to land just any agent, rather than one who already has the connections to sell a particular book. Or that it would be a dandy idea to sending out a barrage of queries to the fifty agents a search engine spit out, or even to every agent in the country, without checking first to see if any of them represent a your kind of book. Or — you might want to put down your fork, the better to digest this one, my dear — to give up after just a few rejections.

Because if that writer were actually talented, how he went about approaching agents wouldn’t matter, would it? The Publishing Fairy would see to it that nothing but the quality of the writing would be assessed — and thus it follows like drowsiness after consuming vast quantities of turkey that if a writer gets rejected, ever, the manuscript must not be well-written. You might as well give up after the first rejection. Or before taking a chance on a query.

Why shouldn’t you, when by prevailing logic, it’s hardly necessary for the writer to expend any effort at all, beyond writing a first draft of the book? Those whom the Publishing Fairy bops in the noggin need merely toss off an initial draft — because the honestly gifted writer never needs to revise anything, right? — then wait mere instants until an agent is miraculously wafted to her doorstep.

Possibly accompanied by Mary Poppins, if the wind is right.

Ah, it’s a pretty fantasy, isn’t it? The agent reads the entire book at a sitting — or, better still, extrapolates the entire book from a swift glance at a query — and shouts in ecstasy, “This is the book for which I have been waiting for my entire professional career!” A book contract follows instantaneously, promising publication within a week. By the end of a couple of months at the very latest, the really talented writer will be happily ensconced on a well-lit couch in a television studio, chatting with a talk show host about her book, pretending to be modest.

“It has been a life-changing struggle,” the writer says brightly, courageously restraining happy tears, “but I felt I had to write this book. As Maya Angelou says, ‘there is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.’”

You would be astonished at the ubiquity this narrative of authorial achievement enjoys amongst aspiring writers. They may not all believe it intellectually — they may have come to understand, for example, that since no agent in the world represents every conceivable type of book, it’s a waste of time to query an agent who does not habitually handle books in one’s chosen book category. At a gut level, however, every rejection feels like just more evidence of being ignored by the Publication Fairy.

Which must mean that the manuscript isn’t nearly as good as you’d thought, right? Why else would an agent — any agent — who has not seen so much as a word of it not respond to a query? The Publication Fairy must have tipped her off that something wasn’t quite as it should be.

Otherwise, where’s Mary Poppins? Aunt Myra may have a point.

‘Fess up — you’ve thought this at time or two. Practically every aspiring writer who did not have the foresight to become a celebrity (who enjoy a completely different path to publication) before attempting to get published entertains such doubts in the dead of night, or at any rate in the throes of being questioned by those with whom one is sharing a gravy boat for the evening. If the road to publication is hard, long, and winding, it must mean something, mustn’t it?

Why, yes: it could mean that the book category in which one happens to be writing is not selling very well right now, for one thing. Good agents are frequently reluctant to pick up even superlative manuscripts they don’t believe they could sell in the current market. It could also signify that the agents one has been approaching do not have a solid track record of selling similar books, or that for querying purposes, one has assigned one’s book to an inappropriate category.

Any of these can result in knee-jerk rejection. Even if a manuscript is a perfect fit and everyone at the agency adores the writing, the literary marketplace has contracted to such an extent in recent years that few agents can afford to take on as many truly talented new clients as they would like.

But those are not the justifications likely to pacify Bernie the Hobgoblin in the night. Nor are they prone to convince Uncle Clark, or make Grandmamma happy, or to awe Roger into the supportive acceptance you would prefer he evince until Cousin Antoinette finally gives him the heave-ho. If only there were some short, pithy quip you could trot out at such instants, if not to cajole these excellent souls into active support, at least to stop them from skewering you when you’re feeling vulnerable.

I cannot give you that magical statement, unfortunately. All I can offer you is the truth: offhand, I can think of approximately no well-established authors for whom the Publishing Fairy fantasy we’ve been discussing represents a real-life career trajectory.

Sorry, Dad — that’s just not how books get published. More pie?

The popular conception of how publishing works is, not to put too fine a point on it, composed largely of magical thinking. All of us would like to believe that if a manuscript is a masterpiece, there’s no chance that it would go unpublished. We cling to the comforting concept that ultimately, the generous literary gods will reach down to nudge brilliant writing from the slush pile (which no longer exists) to the top of the acceptance heap.

We believe, in short, in the Publication Fairy. That’s understandable in a writer: those of us in cahoots with the muses would prefer not to think that they were in the habit of tricking us with false hope. An intriguing belief, given that even a passing acquaintance with literary history would lead one to suspect that the ladies in question do occasionally get a kick out of snatching recognition from someone they have blessed with undoubted talent.

Edgar Allan Poe didn’t exactly die a happy man, people. Oscar Wilde was known to have run into a barrier or two. Louisa May Alcott toiled to churn out potboilers and war anecdotes to pay the coal bill for years before turning to YA, and the primary reason that we know the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley is that his wife happened to be a major novelist and the daughter of two major novelists; Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley was arguably the greatest literary publicist of all time.

And the first novel Jane Austen sold to a publisher? It didn’t come out until after her death.

The muses donate their favors whimsically. I ask you, though, through the lens of that historical perspective: is it really soon enough to judge your writing solely by its immediate commercial prospects? Is it ever?

To non-writers, these perfectly reasonable questions can appear downright delusional, or at the very least confusing. They have no experience having their passions bandied about by the muses, you see. To be fair, you cannot expect otherwise from an upstanding citizen whose idea of Hell consists of a demon’s forcing him into an uncomfortable desk chair in front of a seriously outdated computer and howling, “You must write a book!”

So we are left to ask ourselves: what can such a sterling soul possibly gain by believing that, unlike in literally every other human endeavor, excellence in writing is invariably rewarded? Even those who strenuously avoid bookstores often cling to the myth of the Publication Fairy with a tenacity that makes Santa Claus, the Easter Bunny, and the Tooth Fairy turn chartreuse with envy. If only adults believed in them with such fervor!

If you doubt the strength of the Publication Fairy’s sway, try talking about your writing over a holiday dinner to a group of non-writers who haven’t asked about it. “So when is your book coming out?” that-cousin-whose-relationship-to-you-has-never-been-clear will inquire. “And would you mind passing that mysterious grey substance with which your roommate chose to trouble our family meal?”

“What do you mean, you haven’t finished writing that book yet?” Great-Aunt Mavis chimes in, helping herself to sweet potatoes. “You talked about writing it before Travis here was born, and now he’s on the football squad.”

“Are you still doing that?” Grandpa demands incredulously. “I thought you’d given up when you couldn’t sell your first book. Or is this still the first book?”

Your brother’s wife might attempt to be a bit more tactful; Colleen always tries, doesn’t she? “Oh, querying sounds just awful. Do you really want to put yourself through it? I have a friend who’s self-publishing, and…”

Thanks, Colleen — because, of course, that would never have occurred to you. You’ve never encountered a dank midnight in which you dreamt of thumbing your nose at traditional publishing at least long enough to bypass the querying and submission processes, rush the first draft of your Great American Novel onto bookshelves, and then sit back, waiting for the profits to roll in, the reviewers to rave, and publishers the world over to materialize on your doorstep, begging to publish your next book.

Never mind that the average self-published book sells fewer than five hundred copies — yes, even today — or that most publications that still review books employ policies forbidding the review of self-published books. Half of the books released every year in North America are not self-published, after all. Ignore the fact that all of the effort of promoting such a book falls on the author. And don’t even give a passing thought to the reality that in order for a self-published book to impress the traditional publishing world even vaguely, it typically needs to sell at least 10,000 copies.

Yes, you read that correctly. But the Publishing Fairy can merely wave her wand and change all of that, right?

If she can, she certainly doesn’t do it much. Chant it with me now: agents don’t magically appear on good authors’ doorsteps within thirty seconds of the words The End being typed. But someone predisposed to believe otherwise is also unlikely to understand that when you land an agent, you will not automatically be handed a publication contract by some beneficent deity. If every agented writer had a nickel for each time some well-meaning soul said, “Oh, you have an agent? When’s your book coming out?” we could construct our own publishing house.

We could stack up the first million or so nickels for girders. Mary Poppins could have a flat landing-place made out of dimes.

Try not to hold it against your father-in-law: chances are, he just doesn’t have any idea how publishing actually works.

But you do. Don’t let anybody, not even the insidious hobgoblins of midnight reflection, tell you that the reason you don’t already have a book out is — and must necessarily be — that you just aren’t talented enough. That’s magical thinking, and you’re too smart to buy into it.

I’m not suggesting, of course, that those of you who have yet to dine today deliberately pick a fight with your third cousin twice removed or any other delightful soul considerate enough to inquire about your writing in the immediate vicinity of pickled beets. I sense, though, that more than a few of you would enjoy having a bit of ammunition at the ready in anticipation for that particular battle, should it arise.

Okay, how might one gird one’s loins for that especially indigestible discussion? Had you thought about responding to the question “Published yet, Charlie?” by abruptly asking how everyone at the table feels about the recent election? Or universal healthcare? Or a certain grand jury verdict in Missouri?

You see the point, don’t you? Just as it’s risky to assume that everyone gathered around even the most Norman Rockwell-pleasing holiday table shares identical political beliefs, it’s always dangerous to presume that every kind soul there will be concealing under that sweater-clad chest a heart open to the realities of publishing as it actually occurs. Accepting the probable reality that even the most eloquent explanation will not necessarily sway hearts and minds from devotion to the Publication Fairy may be your best bet.

So what might a writer besieged by the Publication Fairy’s acolytes do to protect her digestion? How about limiting to the discussion to “The writing’s going very well. How’s your handball game these days, Ambrose?”

Seem evasive? Well, it is. But would you rather allow the discourse to proceed to the point that you might have to say to a relative that has just referred to your writing as Allison’s time-gobbling little hobby, “Good one, Sis. Seriously, though, I don’t want to stultify you with an explanation of how books really get published.”

Think about giving it a rest this year, in short. Don’t try to educate everyone in one fell swoop; it’s not your responsibility, and actually, the lecture you give this year may not be sufficiently remembered the next to help you. (Oh, that’s only my in-laws?) Unless you are willing to resign yourself to the inevitability of annual soapbox-mounting, you might want to consider letting your loved ones’ belief in the Publication Fairy survive another holiday season.

If your inherent sense of justice urges you to convey some small sense of your monumental effort toward writing and/or revising, or to share a glimpse into multitudinous stresses involved in querying, submission, and so forth, I’d advise keeping it brief for the purposes of general discussion. It can be easy to become carried away by a topic close to your creative heart, though. If you find yourself starting to launch into a major speech, a simple “Well, I could go on for hours, Horace, but suffice it to say that it’s really hard. I’m trying to take a day off from it, though” can easily bring it to a close. It can also allow you to control how long you’re on the spot.

Oh, now I hear some of you laughing. Yes? “Oh, Anne,” you say, wiping the tears of hilarity from your rosy cheeks, “it’s obvious you have never met my kith/kin/the relative strangers with whom I propose to spend the holiday. I anticipate being confronted not with the casual double-edged question, but with a level of intensive cross-examination and invasive scrutiny from which Perry Mason himself could glean a few pointers. I’m not worried about getting into the conversation; I despair of ever getting out of it.”

A tougher nut to crack, admittedly. I would recommend cutting it off at the first parry. “Wow, that’s a big subject, Gerard,” can often do the trick. Adding “I could prattle for weeks about the behind-the-scenes trials every author faces along the way, but my dinner would get cold, and I so want to hear about Cousin Blanche’s hysterectomy. Ask me again after the dishes are done, when we can make ourselves cozy in a corner and talk. How about during the football game?”

That last bit will, of course, work best if Gerard happens to be a die-hard football fan. It may feel like a low blow, but hey, all’s fair in love, war, and protecting your passions.

If pressed, you could always murmur, “I’d love to continue this fascinating exchange, Hermione, but would you mind if I grabbed my notebook first? Because everyone here is aware that anything you say can and will be used against you in a novel, right?”

An especially judgmental holiday table might be anticipated by the appearance of such a notebook beside your napkin, in fact. As any journalist or rationally self-protective memoirist could tell you, people are apt to clam up a little when they notice their words are being recorded for posterity. Applying pen to paper proactively, accompanied by a slight, rueful shake of the head and a chuckle, will at least turn the conversation from “Why aren’t you published?” to “What are you writing? What did I just say?”

The latter may well be spoken in a resentful tone, but you might be astonished how often it isn’t. Speaking as a memoirist, I’m here to tell you that it never pays underestimate the flattery inherent in finding people interesting enough to occupy page space. I’ve seldom met the Aunt Myra so iron-hearted that “Oh, wow — I’ve just got to write that quip down, Auntie! Talk amongst yourselves while I do” doesn’t soften her will to criticize, at least a little. And it’s a terrific defense for the moment Aunt Gloria decides your rump would benefit from some well-intentioned kicking about not polishing off your revision fast enough.

You could also call upon most people’s active dislike of boredom. An enthusiastic cry of “Oh, my goodness — you have no idea how happy I am that you want to hear all about my writing! Just a sec, while I power up my laptop. The scene I want to read you is a trifle on the long side, but you don’t mind keeping my food warm for me, do you, Eloise?”

Prepare to be stunned by the urgency with which Uncle George and his — what are they called at that age? — great and good friend Carlotta fling themselves into a discussion of the comparative merits of The Blacklist and White Palace as James Spader vehicles at that particular moment. Or Cousin Tremaine’s burning desire to share the scores of each of his eight children’s soccer games. For the last two years.

As I learned at my mother’s knee, any dinner table seating five or more people naturally breaks up into more than one conversation. (My parents threw a lot of literary dinner parties.) Use it.

If the proposed dramatic reading of your own writing doesn’t induce panic, try a burbling offer to declaim that passage in Melville that changed your life forever. Or Proust — in the original French, if necessary. (See earlier observation about what’s fair in love, war, and ego-preservation.)

Let’s assume for the sake of caution, though, that you’re facing a tableful of kith/kin/well-meaning relative strangers breaking bread with you so committed to showing you the error of your writing ways that there’s no graceful way to evade or shorten the conversation. Or that you are dining with a group whose belief in the Publication Fairy is so unquestioning as to border on the childlike (or imbecilic), and you hate the idea of any one of those people’s feeling sorry for you. Or maybe that your obnoxious brother Graham knows that the agent of your dreams has been sitting on your first 50 pages for nine long weeks, and he just enjoys needling you.

Whichever may be the case, what’s a nice (and most writers are nice) writer to do? I would recommend seizing the moment to engage in a little advance education on the practicalities of occupying the inner circle of a published author’s life. The sooner Great-Uncle Vic learns that there’s more to being a famous author’s relative than bragging rights and free books, the more comfortable everyone will be on the happy day when you do in fact become a famous author.

I find that concentrating upon the details tends to go over better than gentle nudges toward a more supportive attitude while folks are gnawing upon drumsticks. I would recommend, in short, of seizing the opportunity of disabusing them of the notion that they’re not going to have to buy your books.

Be prepared for a certain amount of incredulity: next to the Publication Fairy, the notion that authors’ kith and kin routinely receive free copies is one of your more ubiquitous misconceptions. It’s seldom true, at least not to the extent your relatives will think. Yes, Second-Cousin-Thrice-Removed Myrtle, publishers do generally provide their authors with an extremely limited stock of their books, with the expectation that such will be used for promotion. They’re going to want you to pass them along to book reviewers and bloggers and the clerk at your favorite bookstore, not to endow your relatives’ bookshelves, if you catch my drift.

The number of free copies will almost certainly be considerably smaller than either Great-Uncle Vic or Carlotta have been thinking, too. (Oh, you didn’t think he’d been expecting you to send him a signed copy for Carlotta, too? Think again.) Somewhere between 5 and 50 is the norm.

That means, in practice, that if you recklessly promise scads of free copies — and those of us in the biz are perpetually appalled at how often first-time authors often do — you will be facing some hard choices. To whom will you give those precious few books?

Undoubtedly more important to the folks with whom you are currently enjoying turkey, how many of them will not be on that short list? What about the person sitting across the table from you? To your left? To your right?

Before you answer, you might want to take a quick mental count of all the other people who might make sense as recipients. Will you want to send one to your favorite writing teacher? The lady at the archives who took all that extra time to help you research the book? What about your college roommate? Or that blogger who gave you hope when your relatives criticized you? (Oh, yes, authors constantly send me review copies. As much as I appreciate the gesture, please, don’t waste a book on me that you could send to what are euphemistically called opinion-makers: I’d be more than happy with a beautifully-phrased thank-you card, truly.)

All done toting up? Okay, here are 10 free copies. Are there any left for your relatives?

If the answer is no, trust me, it’s better you know it now. It’s also news that you might want to break with great care to your relatives.

Yes, yes, I know: you don’t want to do it. But tell me: will Myrtle be less hurt to hear about it now, or three days before your book drops? What about Uncle George, Aunt Gloria, or the rest of those quadruplets? Honestly, you would be saving them from future disappointment — and yourself from what can be quite a lot of well-intentioned pressure.

Oh, you want a foretaste? How about “What do you mean, you didn’t save a copy for your brother Ralph? You expect someone with whom you shared a bedroom for a decade to pay for his copy?”

Yes, you do. Or you will. It’s not merely that for every copy you give away, that’s one less copy sold. (Who did you think would buy your book, if not your kith, kin, and everyone who has ever known you?) That ultimately means fewer royalties for you, as well as possibly a harder time convincing a publisher to bring out your next book.

Not that it would be remotely politic to express any of this so bluntly, of course. Phrase it as gently as you know how; it will come as a blow to folks expecting not only never to have to pay a dime for a single word of your writing, but possibly — brace yourself — having also presumed that they would be on the receiving end of copies to distribute to their friends. (Hey, it’s a common fantasy amongst the author-adjacent.)

Just bear in mind that by speaking now, you’re ultimately saving the people you love from chagrin. If that doesn’t do the trick, try recalling that if you recklessly promise free copies — and again, those of us in the biz are positively aghast at how many first-time authors have — you will almost certainly be buying those gift copies yourself.

I don’t mean that conceptually, by the way: it’s exceedingly common for first-time authors to end up actually purchasing individual copies for their relatives and friends. To see why, you need only revisit that mental list of gift recipients.

That’s a difficult reality to accept, isn’t it? I can tell you now that you’re going to feel mean as you convey this information. Feel free to blame me as the source of the bad news: trust me, it would not be the first time “You’re not going to believe what I read on Author! Author!” was used as a blow-softener. I’m tough; I can take it.

More to the point, I’m not having Thanksgiving dinner with you, am I?

I can, however, anticipate your mother’s first tremulous question, and possibly yours: yes, authors do generally receive fairly substantial discounts on their own books, as long as those books are purchased directly from the publisher (and, in many cases, ordered in advance of the release date). Houses like to encourage their authors to carry around copies to resell to anyone who says, “Oh, you have a book out? Cool!”

That’s why, in case you’ve been wondering, authors so often show up at reading venues staggering under heavy backpacks or enormous purses. If the venue’s not a bookstore, those authors usually have a box or two of books in their cars, ready to pile in an attractive display next to the podium. (What, you thought the Publication Fairy brought them?)

What may interest you more than your mother to hear, however, is that copies purchased with the author’s discount virtually never count toward a book’s sales totals — and thus not toward royalties. That hefty discount arises from your price’s not reflecting royalty costs or negotiated deals with booksellers, you see. (You’re going to want to check your publishing contract carefully on this point; sometimes, it’s negotiable, as is the number of free copies.) A cost-conscious writer might also like to know before promising copies that one’s agent or acquiring editor might not think to point out that buying a lot of discounted books might not be to the author’s advantage.

They tend to assume that the bit about those copies’ not adding toward sales totals is quite a bit more widely known than it actually is; it’s not unheard-of for this tidbit not to be discussed at all at contract time, or even as the book is moving toward publication. The author usually hears about the number of free copies (“There you go, Mom!”) and the discount (“Okay, Great-Uncle Vic can think that his was free.”), but simply assumes that a book sold is a book sold. Why wouldn’t a discounted copy be included in the overall total and generate royalties?

Don’t believe that often comes as an unpleasant surprise? As recently as last week, I was chatting with a quite successful first-time memoirist. Her excellent book came out earlier this year, and, as is so often the case, she had underestimated the unpaid time, effort, and expense an author at a major house is routinely expected to devote to book promotion. She was particularly annoyed to learn that she had to buy and pay to ship 50 copies of her book to a speaking venue — and then to pay to have the 42 that hadn’t sold at the event shipped to her home. She wasn’t sure, she said, that she would be willing to do it again.

I commiserated. “And to think that after all that effort, those books will have no effect on your book’s sales totals. I’m so sorry.”

“Wait,” she said. “What? I won’t get royalties?”

So no, Mom, your baby’s probably not going to be coughing up the cover price for a copy for you, but it may be costly in other ways. Your in-house author may even be able to shake free a gratis copy for Great-Grandma Midge, who isn’t getting any younger, but please don’t feel guilty. Mom might want to get into the habit of telling more distant relatives — like, say, those cousins she made you invite to your wedding, although you hadn’t seen them since you were six — that they should plan on buying their own copies. You would be delighted to sign them afterward.

Trust the voice of experience: the more special she feels at the prospect of clutching her own free book — the only one in the family, because you’re such a good kid! — the more likely she is to go to bat for you. “Every single copy Tammy sells helps her,” she can say — and she’ll get better with practice. “I’ll understand if you can’t afford it, of course. She’s been working so hard for so many years on this book, but please don’t feel guilty.”

Translation: the best thing Aunt Myra could do to support your writing career would be to commit to buying your book(s) herself. Promise to sign it for her the instant she does. If you’re feeling adventurous, extend that promise to visiting her in order to inscribe copies for all of the friends she can cajole, blandish, and/or guilt into purchasing.

I have faith in your Aunt Myra. I think she can push some volumes.

All that being said, don’t kick yourself if you find you don’t have the heart to tell your relatives and friends any of this in the course of the current holiday season. This is big stuff, and even the best of us have people in our lives prone to judging the quality of a book by its position on the bestseller list. You have to pick your battles. You might want to bookmark this page, though, so you have the arguments handy down the line.

Heck, you could just forward the link to your kith and kin a few months before your first book comes out. Again, I don’t mind playing the heavy here, if it helps you. I’ve spent a lifetime explaining to everyone’s relatives that since the Publication Fairy so often falls down on the job, it’s up to the rest of us to support the writers in our lives.

I see no reason to stop now. Your writing deserves it, doesn’t it?

And you have that support within our Author! Author! community. Here, we don’t dismiss every book that doesn’t sell 150,000 copies. We don’t feel that large print contributes more to reading pleasure than the style of the writing. (Take that, Madame de Sévigné!) And most of all, we don’t believe in the Publication Fairy.

It’s sweet, in a way, that so many people do. By that logic, the Followers of the Fairy incur a greater obligation than the rest of us to buy the books of authors they know personally: the Fairy, and the industry, can only reward with success books that readers purchase. Anyone who wants to judge your dream to write by that yardstick should understand that they can, with a good will and the best of intentions, contribute to your sales totals. And thus to their opinion of the value of your writing endeavors.

As always, keep up the good work. Happy digestion to all, and to all a good night.