Yes, sharper-eyed readers, that is a gnome sitting on top of the retreat sign — the famous Norcroft gnome, in fact. The Norcroft retreat has gone the way of all flesh, alas, but its basic principle lives on: no matter how well-organized a writer is, from time to time, it’s helpful to the productivity to cut oneself off from the myriad demands of quotidian life, go someplace strange, and just write.

And before any of you get your hopes up: neither your boss, coworkers, friends, nor family will understand this time to be work, rather than a vacation. No, not even if you spend 18 hours a day writing on retreat. Sorry about that.

That remains true, incidentally, no matter how thoroughly you become established as an author. As my sister-in-law put it only this weekend upon seeing me still blear-eyed from 13-hour days of writing and lingering jet lag, “Oh, five weeks in France. Hard to have much sympathy for that.”

She’s one of my more sympathetic sisters-in-law, incidentally.

Because I’ve just been on a lengthy I’ve been chattering off and on for the last couple of months about the joys and drawbacks of formal writing retreats — the group kind, organized by other people — as opposed to the informal type where you find a peaceful place and lock yourself in for a week or two along with a crate of apples, gallons of coffee, and the makings of 150 peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. While the latter type tends to be significantly less expensive, particularly if you happen to know someone who is willing to let you house-sit for a while, the former have many inherent advantages.

Not the least of which: many of them award fellowships to writers. So, perversely, a month at a formal fellowship at an artists’ colony could actually end up being less costly than a week at the Bates Motel, munching Power Bars. Not to mention making for better ECQLC (eye-catching query letter candy).

A whole bunch of eyebrows just shot skyward, didn’t they? “Okay, Anne,” eager beavers everywhere shout. “What is a fellowship, and how do I go about landing me one?”

Fellowships vary quite a bit, offering everything from work space at universities (like Stanford’s Wallace Stegner Fellowship, which pays fellows $26,000/year, plus tuition and health insurance, to attend one 3-hour writing seminar per week for two years) to actual apartments and a living stipend (like the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown) to financial aid so writers can attend well-respected workshops (like the Squaw Valley Writers’ Workshops reduced-cost or free week- or month-long residencies at artists’ colonies (too numerous to pick just one example).

A great place to look for reputable fellowship opportunities is the back of Poets & Writers magazine. Before you start tearing through their listings, you should know that a few things are true of virtually all of them:

(1) All require fairly extensive applications, so plan to devote some serious time to filling them out prior to the deadline.

(2) Even for a residency for which you pay (or pay in part), you will almost certainly have to pass through a competitive process, known in the biz as writing your way in.

(3) Any merit-based fellowship (as most that accept previously unpublished writers are) will require a writing sample, so do burnish the first chapter of your book, a representative short story or two, or a collection of poems to a high gloss before you start applying.

(4) There will be heavy competition for any that offer serious money or substantial retreat time, so it’s generally not worth the sometimes-hefty application fee for a new writer to submit a first manuscript. Although of course some absolute beginners do win occasional fellowships, unpolished work tends to get knocked out of consideration early in the competition.

(5) Yes, I said application fee — most fellowships require them, and they’re not always cheap. (If you’re a US-based writer who files a Schedule C for your writing business, these fees may be tax-deductible, even in a year that you don’t actually make any money from your writing; consult a tax specialist familiar with writers’ — not just artists’ — returns to see if you are eligible.)

(6) Some ask for references, so if you happen to be a nodding acquaintance of a relatively well-known writer or writing teacher, you might want to be extra-nice to them right about now.

(7) Most residencies and the more prestigious fellowships look more kindly upon applicants who already have some publications (surprisingly, even if they say they are specifically looking for up-and-coming writers), previous contest wins, or have already done a residency. Think about applying for something small, then working your way up to the more prestigious and lucrative residencies.

(8) In comparing fellowships with residencies for which you would have to pay outright, be sure to factor in expenses that a fellowship would not cover. Virtually no fellowship will cover airfare or other travel expenses to get to a far-flung retreat, for instance; some feed residents and some don’t. This is why, in case any of you have been wondering, one of the first questions an experienced retreater will ask about a residency is, “Do they feed you?” (Don’t worry; more on that last part follows below.)

And remember, unless a fellowship provides a stipend, you still will be responsible for paying your bills while you’re taking time off work to go on retreat.

(9) Most mixed artists’ colonies — i.e., those that welcome both writers and other sorts of artists — will harbor at least a slight institutional bias toward a particular kind of art. Even if it is equally hard for every type of artist to win a fellowship or a residency charges every type of artist the same, the work spaces available may differ widely. So if the resources for sculptors are spectacular, triple-check that the writers aren’t just shoved in a windowless basement and told to get on with it. (Yes, I’ve seen it happen.)

I’ve been sensing some uncomfortable shifting in desk chairs as I’ve been running down that list. “Um, Anne?” I hear some of you pointing out timidly. “Correct me if I’m wrong, but this doesn’t sound like any less work than submitting to an agent. Or to a literary contest, for that matter. Isn’t the whole point of this to gain more time for my writing, not to sap energy from it?”

Congratulations, timid question-askers: you’ve got a firm grasp of the dilemma of the fellowship-seeking writer. Well, my work here is done, so I’ll be signing off for the evening…

Just kidding. Just as when you are seeking out an agent or small press, it’s in your interest to do a bit of checking before you invest too in pursuing any individual fellowship opportunity. I’m not merely talking about entry fees here, either — it will behoove you to ask yourself while those dollar signs are dancing in your eyes, “Will applying for this fellowship take up too much of my writing time?

To assist you in making that assessment, let’s go over some of the potentially most time-devouring common requirements, shall we?

Unfortunately, there are few fellowship out there, especially lucrative ones, that simply require entrants to print up an already-existing piece of writing, slide it into an envelope, write a check for the application fee, and slap a stamp upon it. Pretty much all require the entrant to fill out an entry form, which range from ultra-simple contact information to demands that you answer essay questions.

Do be aware that every time you fill out one of these, you are tacitly agreeing to be placed upon the sponsoring organization AND every piece of information you give is subject to resale to marketing firms, unless the sponsor states outright on the form that it will not do so. (Did you think those offers from Writers Digest and The Advocate just found their way into your mailbox magically?) As with any information you send out, be careful not to provide any information that is not already public knowledge.

How do you know if what is being asked of you is de trop? Well, while a one- or at most two-page application form is ample for a literary contest, a three- or four-page application is fair for a fellowship. Anything more than that, and you should start to wonder what they’re doing with all of this information. A fellowship that gives out monetary awards will need your Social Security number eventually, for instance, but they really need this information only for the winners. I would balk about giving it up front, unless the organization is so well-established that there’s no question of misuse.

As I mentioned above, it’s surprisingly common for fellowship applications (and even some contest entry forms) to ask writers to list character references — an odd request, given that the history of our art form is riddled with notorious rakes. Would a fellowship committee throw out the work of a William Makepeace Thackeray or an H.G. Wells because they kept mistresses…or disqualify Emily Dickinson’s application to spend a few months locked in a sunny room near a beach somewhere because her neighbors noticed that she didn’t much like to go outside when she was at home?

Actually, residencies often don’t actually check these references, even for fellowship winners; they usually merely ask for names and contact information, not actual letters of reference. My impression is that it’s usually a method of discouraging writers who have not yet taken many writing classes, gone to many conferences, or otherwise gotten involved in a larger writers’ community from applying, on the theory that they might not be as likely to respect other fellows’ working boundaries. I suppose it’s also possible, though, that they want to rule out people whose wins might embarrass the fellowship-granting organization, so they do not wake up one day and read that they gave their highest accolade and a $30,000/year stipend to Ted Bundy.

I guess that’s understandable, but frankly, I would MUCH rather see mass murderers, child molesters, and other violent felons turning their energies to the gentle craft of writing than engaging in their other, more bloody pursuits; some awfully good poetry and prose has been written in jail cells. I do not, however, run an organization justifiable fearful of negative publicity.

I sense that the more suspicious-minded among you have come up with yet another reason a fellowship or contest application might request references, haven’t you? “Yes, I can,” a few voices reply. “If an applicant lists someone who has already won that particular fellowship as a reference, or someone on the staff of the artists’ retreat, is the application handled differently? If I can list a famous name as a reference, are my chances of winning better?”

Only the judging committee knows for sure. But if you can legitimately manage to wrangle permission from a former winner, staff member, or Nobel laureate to use ‘em as a reference, hey, I would be the last to try to stop you.

You can also save yourself a lot of time if you avoid fellowship applications that make entrants jump through a lot of extraneous hoops in preparing a submission. Specific typefaces. Fancy paper. Odd margin requirements. Expensive binding. All of these will eat up your time and money, without the end result’s being truly indicative of the quality of your work – all conforming with such requirements really shows is that an applicant can follow directions.

My general rule of thumb is that if a writer can pull together an application or contest entry with already-written material within a day’s worth of writing time, I consider it a reasonable investment. If an application requires time-consuming funky formatting, or printing on special forms, or wacko binding, I just don’t bother anymore, because to my contest-experienced eyes, these requests are not for my benefit, but theirs.

How is that possible, you cry? Because — and this should sound familiar to those of you have perused my posts on preparing a contest entry — the primary purpose of these elaborate requests for packaging is to make it as easy as possible to disqualify applications in a large applicant pool. By setting up stringent and easily-visible cosmetic requirements, the organizers have maximized the number of applications they can simply toss aside, largely unread: the more that they ask you to do to package your application, the more ways you can go wrong. (For a plethora of disturbingly common ways in which fellowship applications and contest entries DO go wrong, please see the CONTEST ENTRY BUGBEARS category on the archive list at right.)

I’m happy to report, though, that this weeding-out strategy is less common in fellowship applications than in literary contests. However, in a tight competition, a professionally-presented manuscript excerpt will almost always edge out one that isn’t. (If you don’t know the cosmetic differences between a professional manuscript and any other kind, please see the posts under HOW TO FORMAT A MANUSCRIPT and STANDARD FORMAT ILLUSTRATED on the list at right before you even consider applying for a literary fellowship or residency in North America.)

And for the benefit of all of you who just rolled your eyes at that suggestion: I’m just trying to save you some money here. Including a writing sample that isn’t technically perfect — spell-checked, grammatically impeccable, and in standard format — is virtually always simply a waste of an application fee.

Speaking of saving some money, most fellowship- and residency-seeking writers automatically assume that a retreat that provides its residents with regular meals will automatically be less expensive to attend than one that doesn’t. However, that’s not always the case. Having been in residence at both artists’ retreats that fed their residents and those that left them to their own devices — as well as one that marched the middle ground of asking residents for a shopping list and buying us food for us to prepare ourselves — I can envision several reasons you might want to give the gift horse of three cafeteria meals per day a pretty thorough dental examination before you agree to pay extra for it.

“Wait a minute,” some of you just exclaimed. “What do you mean, pay extra for food? Aren’t we talking about retreats where meals are just included in the price — or as part of the fellowship?”

Well, it all depends upon how you choose to look at it. Retreats that provide meals usually do include them as part of a fat fee. They also tend to charge residents more per day than those that do not.

And not necessarily in cash; many artists’ colonies require residents (yes, even fellowship winners) to participate in meal preparation, serving, and clean-up in addition (or instead of) charging for food. So if you’re looking forward to a retreat as a break from cooking for your kith and kin, you will want to read the fine print in its entirety.

If you are seriously interested in a retreat with a pitching-in requirement, e-mail the retreat’s organizers and ask for an estimate of how many hours per week residents are typically expected to contribute. Since many kitchen tasks involve repetitive motion and hand strain, if you have any history whatsoever with repetitive strain injuries, you might want to ask if there are alternative tasks you could do instead, in order to reserve your hand use time for the writing you went on retreat to do.

Here’s the good news for those with aching hands: surprisingly often, residencies that require chores are open to residents buying their way out of them, provided that not everyone in residence has the same bright idea, and the price tag isn’t always particularly expensive. In fact, I’ve attended residencies where I was downright insulted at just how little the organizers evidently thought my time was worth.

How little, you ask? Well, they expected me to rearrange my writing schedule so I could be awake enough to wield a chef’s knife at 6 am four days per week for a month-long residency, regularly requesting my shift to stay on until lunch was served, so we’re talking about a half-time job. Even if they’d calculated it at minimum wage, it probably would have been worth my while to scrape the bottom of bank account to save myself the wrist strain. But in their excellent judgment, digging that deeply into my writing schedule was worth about a third of that.

I would just love to answer that question that half of you just howled at your computer screen, but it’s against my policy to use Author! Author! space for undeserved free advertising. Suffice it to say that if you ask writers who have won fellowships to this particular artists’ colony, most say that they would not consider returning, even though I understand that now the writers’ building does boast some windows, and not all of us had to buy air mattresses to render the mattresses on top of plywood bed frames possible to sleep upon. My bedroom was the only one that had an active hornet’s nest in it, but honestly, I only needed to worry about being dive-bombed when the heater was working.

But that hardly ever happened.

None of that is exaggeration; see my earlier comment about how much fellowship offerings vary. You’d have thought that the fact that it was an expensive artists’ retreat — one of the largest in the United States; it may now actually be the largest — would have dictated better conditions, but believe it or not, the competition to put up with these conditions was extremely stiff.

Incidentally, that particular retreat looked very, very good in its brochures, as well as on its website. As I recall, the food situation was described to potential fellowship applicants a little something like this: Our chef provides three meals per day. Meals feature fresh breads, homemade desserts, soups and a full salad bar. Fresh produce from local, organic farms is used whenever possible. Vegetarian main courses are offered several times a week, but not daily. Regrettably, we are not able to provide for special dietary needs.

Did those last couple of sentences startle some of you? You might want to keep an eye out for similar statements in we-feed-you residencies, but such sentiments provide a clue that been fed might prove more expensive for some attendees than others. Not only were vegetarians and vegans reduced to relying almost exclusively on a not especially exciting salad bar (the object of my early-morning chopping efforts, so I became intimately familiar with its never-changing options), but anyone with problems digesting wheat, dairy, sugar, gluten, peanuts, soy, MSG (present, as nearly as I could tell, in every soup served), or any of the other most common food allergens simply had to eat someplace else.

Why? Because when the chef assumes that anyone who can’t eat something in the entree he’s serving twice per week will simply make himself a peanut butter and jelly sandwich with a glass of milk, anyone with any of the first five restrictions listed is left without an option that won’t make her ill. And although the fresh bread was tasty, the chopping board was immediately adjacent to the salad bar, so the greens were continually dusted with crumbs. (If that last sentence didn’t make you instinctively clutch at your entrails, you probably neither have nor know anyone with celiac disease.)

Would you have guessed all that from a quick glance at the blurb above? Or budgeted for the necessary additional meals?

Even if you don’t have any dietary restrictions, unless a retreat is well-known for yummy food, being fed doesn’t necessarily mean being fed well. Although retreat food is almost invariably cafeteria-quality food (washed down with, alas, cafeteria-quality coffee), it may not be priced accordingly; if you are not a three-meal-per-day person or not a great lover of dry lasagna, you might actually save money by opting out of the meal plan — or by choosing a residency that doesn’t insist upon feeding you.

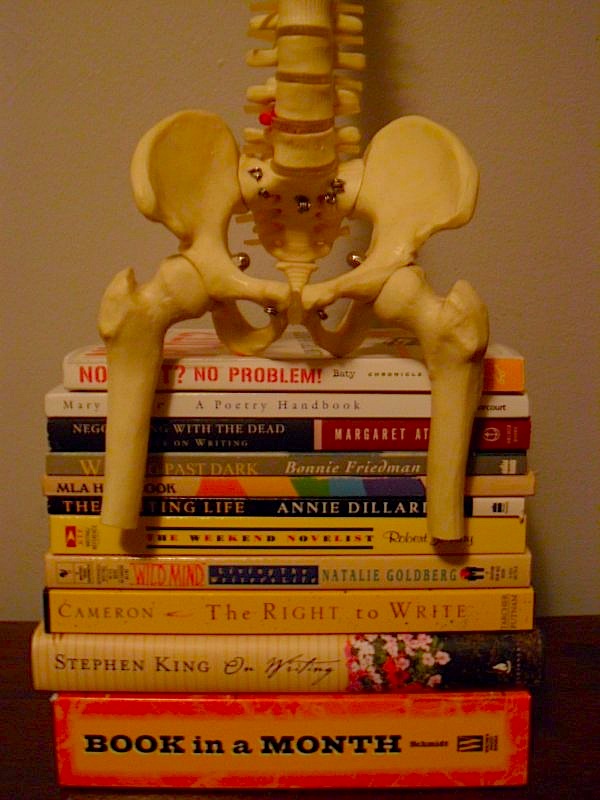

Feeding yourself does have its drawbacks, of course: it can be time-consuming, especially if there isn’t a well-stocked grocery store or inexpensive restaurant close to the retreat. (Since retreats are often plopped down in remote places, not having a store or café within easy walking distance is not out of the question.) Even if residents have access to a kitchen, it may not be well-equipped, so you may end up needing to import basics like a good chopping knife — I’ve never known a retreat to be home to a decent one — or a whisk.

Interestingly, good cooks can find feed-yourself retreats a bit trying. Due to some divine oversight, cooking skills are not equally distributed across the human population, so the culinary gifted often find themselves and their plates on the receiving end of puppy-like stares from fellow residents incapable of boiling water successfully. After three or four straight days of watching a nice fellow resident dine on peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on white bread, I usually can’t stand it anymore and start cooking vats of vegetables for communal consumption.

Time-consuming? Potentially, but at least it’s a matter of personal choice. If I don’t feel like helping the cooking-impaired stave off imminent malnutrition, I can always just walk away from the kitchen whenever the peanut butter jar is open.

Which brings me to one of the main reasons I’m not a huge fan of we-feed-you residencies: you have to eat at specific times. If you are feeding yourself, you don’t have to interrupt your work to rush to the dining hall.

To be fair, for writers who already habitually eat at the predetermined hours, this may not represent much of an interruption, but I usually find the mealtimes inconvenient. I suspect that I’m not alone in this. Although a hefty percentage of writers are at their most creative at night, for some reason beyond my ken, meals at retreats tend all to be during the daylight hours, say 8-9 am for breakfast, 12-1 for lunch, and 6-7 pm for dinner. Great if you happen to arise at the crack of dawn and hit the hay by 10 pm, but downright disruptive should you be a night owl.

The fact that I’m posting this at midnight should give you some hint into which category yours truly is likely to fall. Hoot, hoot — and what do you mean, my pitching-in shift starts at 6 am?

More on the day-to-day practicalities of life at a formal writing retreat follows in the days to come. Keep up the good work!

Annemarie Monahan is still able to read the Latin of her diploma from Bryn Mawr College, a skill as practical as her degree in English. Belatedly realizing she had to eat, she earned her professional doctorate from Northwestern College of Chiropractic.