Okay, I’ll confess it: I find writing for an audience as diverse as the Author! Author! community more gratifying than I would addressing a readership more uniformly familiar with the ins and outs of the writing world. I particularly like how differently all of you respond to my discussions of fundamentals; it keeps me coming back to the basics with fresh eyes.

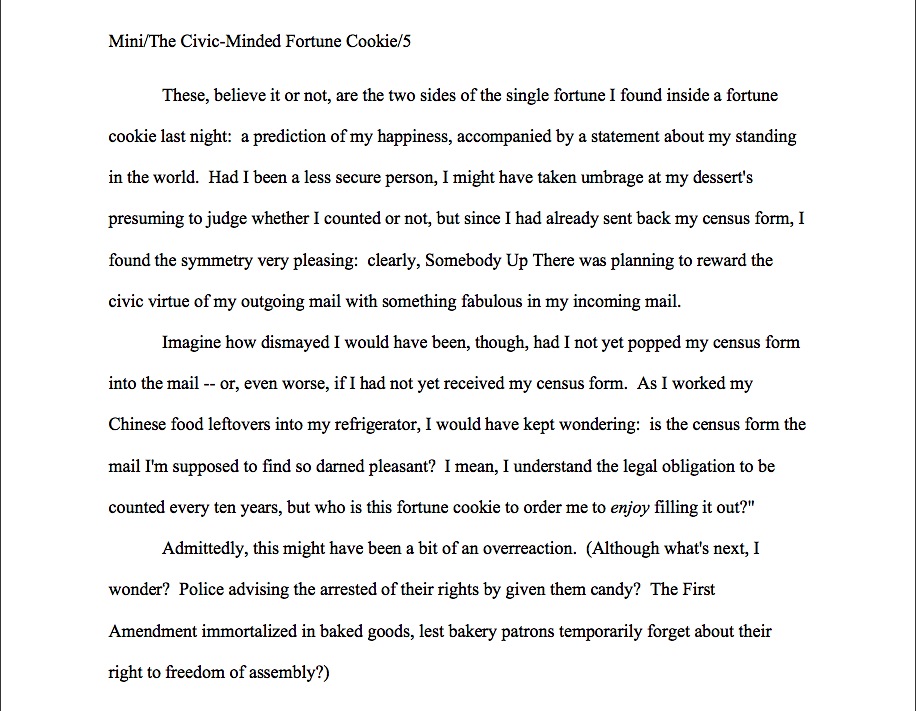

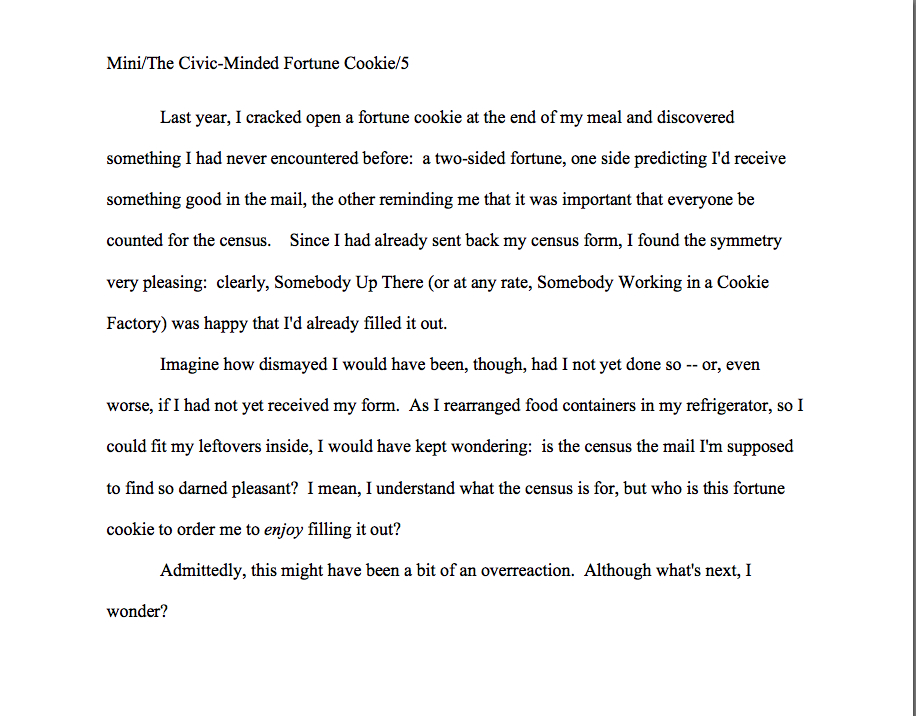

I constantly hear from those new to querying and synopsis-writing, for instance, that the challenge of summarizing a 400-page manuscript in a paragraph — or a page, or five — strikes them as almost as difficult as writing the book they’re describing; from the other direction, those of us who read for a living frequently wonder aloud why someone aiming to become a professional writer would complain about being expected to write something. A post on proofreading might as easily draw a behind-the-scenes peek at a published author’s frustration because the changes she made in her galleys did not make it into her book’s first edition as a straightforward request from a writer new to the challenges of dialogue that I devote a few days to explaining how to punctuate it.

And then there are days like today, when my inbox is crammed to overflowing with suggestions from all across the writing spectrum that I blog about a topic I’ve just covered — and approach it in a completely different way, please. All told, within the last week, I’ve been urged to re-tackle the topic in about thirty mutually-exclusive different ways. In response to this barrage of missives, this evening’s post will be devoted to the imperative task of repairing a rent in the fabric of the writing universe that some of you felt I left flapping in the breeze.

In my appropriately peevish post earlier this week about the importance of proofreading your queries — and, indeed, everything in your query packet — down to the last syllable in order to head off, you guessed it, Millicent the agency screener’s pet peeves in the typo department, my list of examples apparently omitted a doozy or two. Fortunately, my acquaintance amongst Millicents, the Mehitabels who judge writing contests, the Maurys that provide such able assistance to editors, and the fine folks employing all three is sufficiently vast that approximately a dozen literature-loving souls introduced my ribcage to their pointy elbows in the interim, gently reminding me to let you know about another common faux pas that routinely makes them stop reading, clutch their respective pearls, and wonder about the literacy of the writer in question.

And if a small army of publishing types and literature aficionados blackened-and-blued my tender sides with additional suggestions for spelling and grammar problems they would like to see me to address in the very near future, well, that’s a matter between me, them, and my chiropractor, is it not? This evening, I shall be concentrating upon a gaffe that confronts Millicent and her cohorts so often in queries, synopses, book proposals, manuscripts, and contest entries that as a group, they have begun to suspect that English teachers just aren’t covering it in class anymore.

Which, I gather, makes it my problem. Since the mantle of analysis is also evidently mine, let me state up front that I think it’s too easy to blame the English department for the popularity of the more pervasive faux pas. Yes, many writers do miss learning many of the rules governing our beloved language, but that’s been the norm for most of my lifetime. Students have often been expected to pick up their grammar at home. Strange to relate, though, houses like the Mini abode, in which children and adults alike were expected to be able to diagram sentences at the dinner table, have evidently never been as common as this teaching philosophy would imply.

Or so I surmise from my friends’ reactions when I would bring them home to Thanksgiving dinner. Imagine my surprise upon learning that households existed in which it was possible for a diner without a working knowledge of the its/it’s distinction to pour gravy over mashed potatoes, or for someone who couldn’t tell a subject from a predicate to ask for — and, I’m incredulous to hear, receive — a second piece of pumpkin pie. Garnished with whipped cream, even.

So where, one might reasonably wonder, were aspiring writers not taught to climb the grammatical ropes either at home or at school supposed to pick them up? In the street? Ah, the argument used to go, that’s easy: they could simply turn to a book to see the language correctly wielded. Or a newspaper. Or the type of magazine known to print the occasional short story.

An aspiring writer could do that, of course — but now that AP standards have changed so newspaper and magazine articles do not resemble what’s considered acceptable writing within the book publishing world (the former, I tremble to report, capitalizes the first letter after a colon, for instance; the latter typically does not), even the most conscientious reader might be hard-pressed to derive the rules by osmosis. Add in the regrettable reality that newspapers, magazines, and even published books now routinely contain typos, toss in a dash of hastily-constructed e-mails and the wildly inconsistent styles of writing floating about the Internet, and stir.

Voil? ! The aspiring writer seeking patterns to emulate finds herself confronted with a welter of options. The only trouble: while we all see the rules applied inconsistently all the time, the rules themselves have not changed very much.

You wouldn’t necessarily know that, though, if your literary intake weren’t fairly selective. Take, for instance, the radically under-discussed societal decision to throw subject-object agreement in everyday conversation out with both the baby and the bathwater — contrary to popular practice, it should be everyone threw his baby out with the bathwater, not everyone threw their baby out with the bathwater, unless everyone shared collective responsibility for a single baby and hoisted it from its moist settee with a joint effort. This has left many otherwise talented writers with the vague sense that neither the correct usage nor the incorrect look right on the page.

It’s also worth noting that as compound sentences the length of this one have become more common in professional writing, particularly in conversational-voiced first person pieces, the frequency with which our old pal, Millicent the agency screener, sees paragraph- or even page-long sentences strung together with seemingly endless series of ands, buts, and/or ors , has skyrocketed, no doubt due to an understandable cognitive dissonance causing some of the aforementioned gifted many to believe, falsely, that the prohibitions against run-on sentences no longer apply — or even, scare bleu, that it’s actually more stylish to cram an entire thought into a single overstuffed sentence than to break it up into a series of shorter sentences that a human gullet might conceivably be able to croak out within a single breath.

May I consider that last point made and move on? Or would you prefer that I continue to ransack my conjunctions closet so I can tack on more clauses? My neighborhood watch group has its shared baby to bathe, people.

It’s my considered opinion that the ubiquity of grammatical errors in queries and submissions to agencies may be attributable to not one cause, but two. Yes, some writers may never have learned the relevant rules, but others’ conceptions of what those rules are may have become blunted by continually seeing them misapplied.

Wait — you’re just going to take my word for that? Really? Have you lovely people become too jaded by the pervasiveness or sweeping generalizations regarding the decline of grammar in English to find damning analysis presented without a shred of corroborative evidence eye-popping? Or to consider lack of adequate explanation of what I’m talking about even a trifle eyebrow-raising?

Welcome to Millicent’s world, my friends. You wouldn’t believe how queries, synopses, and opening pages of manuscripts seem to have been written with the express intention of hiding more information from a screener than they divulge. They also, unfortunately, often contain enough spelling, grammar, and even clarity problems that poor Millie’s left perplexed.

Doubt that? Okay, let’s examine a not-uncommon take on the book description paragraph from a query letter:

OPAQUE is the story of Pandora, a twenty eight year old out of work pop diva turned hash slinger running from her past and, ultimately, herself. Fiercely pursuing her dreams despite a dizzying array of obstacles, she struggles to have it all in a world seemingly determined to take it all away. Can she find her way through her maze of options while still being true to herself?

Excuse me, but if no one minds my asking, what is this book about? You must admit, other than that long string of descriptors in the first sentence, it’s all pretty vague. Where is this story set? What is its central conflict? What is Pandora running from — or towards — and why? And what about this story is better conveyed through hackneyed phrasing — running from her past, true to herself — than could be expressed through original writing?

On the bright side, Millicent might not stick with this query long through enough to identify the clich? use and maddening vagueness as red flags. Chances are, the level of hyphen abuse in that first sentence would cause her to turn pale, draw unflattering conclusions about the punctuation in the manuscript being offered, and murmur, “Next!”

I sense some of you turning pale at the notion that she might read so little of an otherwise well-crafted query, but be honest, please. Are you wondering uneasily how she could possibly make up her mind so fast — or wondering what about that first sentence would strike a professional reader as that off-putting?

If it’s the latter, here’s a hint: she might well have lasted to be irritated by the later ambiguity if the first sentence had been punctuated like this.

OPAQUE is the story of Pandora, a twenty-eight-year-old out-of-work pop-diva-turned-hash-slinger running from her past and, ultimately, herself.

Better, isn’t it? While we’re nit-picking, the TITLE is the story of… is now widely regarded as a rather ungraceful introduction to a query’s descriptive paragraph. Or as an opening for a synopsis, for that matter. Since Millicent and her boss already know that the purpose of both is — wait for it — to describe the book, why waste valuable page space telling them that what is about to appear in the place they expect to see a book description is in fact a book description?

There’s a larger descriptive problem here, though. If the querier had not attempted to shove all of those multi-part descriptive clauses out of the main body of the sentence, the question of whether to add hyphens or not would have been less pressing. Simply moving the title to the query’s opening paragraph, too, would help relieve the opening sentence of its heavy conceptual load. While we’re at it, why not give a stronger indication of the book’s subject matter?

As a great admirer of your client, A. New Author, I am writing in the hope you will be interested in my women’s fiction manuscript, OPAQUE. Like Author’s wonderful debut, ABSTRUSE, my novel follows a powerful, resourceful woman from the public spotlight to obscurity and back again.

By the tender age of twenty-eight, pop sensation Pandora has already become a has-been. Unable to book a single gig, she drives around the back roads of Pennsylvania in disguise until she finds refuge slinging hash in a roadside diner.

Hooray — Millicent’s no longer left to speculate what the book’s about! Now that the generalities and stock phrases have been replaced with specifics and original wording, she can concentrate upon the story being told. Equally important, she can read on without having to wonder uneasily if the manuscript will be stuffed to the proverbial gills with typos, and thus would not be ready for her boss, the agent of your dreams, to circulate to publishing houses.

While I appreciate the refreshing breeze coming from so many heads being shaken simultaneously, I suspect it indicates that not everyone instantly spotted why a professional reader would so vastly prefer the revised versions to the original. “I do like how you’ve unpacked that overburdened first sentence, Anne,” some brave souls volunteer, “but I have to say, the way you have been moving hyphens around puzzles me. Sometimes, I’ve seen similar phrases hyphenated, but sometimes, they’re not. I thought we were striving for consistency here!”

Ah, a common source of confusion: we’re aiming for consistency in applying the rules, not trying, as so many aspiring writers apparently do, to force the same set of words to appear identically on the page every time it is used. The first involves learning the theory so you can use it appropriately across a wide variety of sentences; the second entails an attempt to memorize how certain phrases appear in print, in an attempt to avoid having to learn the theory.

Trust me, learning the rules will be substantially less time-consuming in the long run than guessing. Not to mention more likely to yield consistent results. Oh, and in the case of hyphens, just trying to reproduce how you saw a phrase used elsewhere will often steer you wrong.

Why? Stop me if this sounds familiar: anyone who reads much these days, especially online, routinely sees more than his share of hyphen abuse. Hyphens crop up where they don’t belong; even more frequently, they are omitted where their inclusion would clarify compound phrasing. No wonder writers — who, after all, tend to read quite a bit more than most people, and certainly read with a closer eye for picking up style tips — sometimes become confused.

And frankly, queries, synopses, book proposals, and manuscripts reflect that confusion. You’d be amazed at how often aspiring writers will, on a single page, hyphenate a phrase correctly on line 5, yet neglect to add a hyphen to a similar phrase on line 18. Or even, believe it or not, present the same phrase used in precisely the same manner in two different ways.

Which raises an intriguing question, doesn’t it? Based on that page, how could Millicent tell whether a sentence was improperly punctuated because the writer was in a hurry and just didn’t notice a one-time typo in line 18 — or if the writer didn’t know the rule in the first place, but guessed correctly on line 5? The fact is, she can’t.

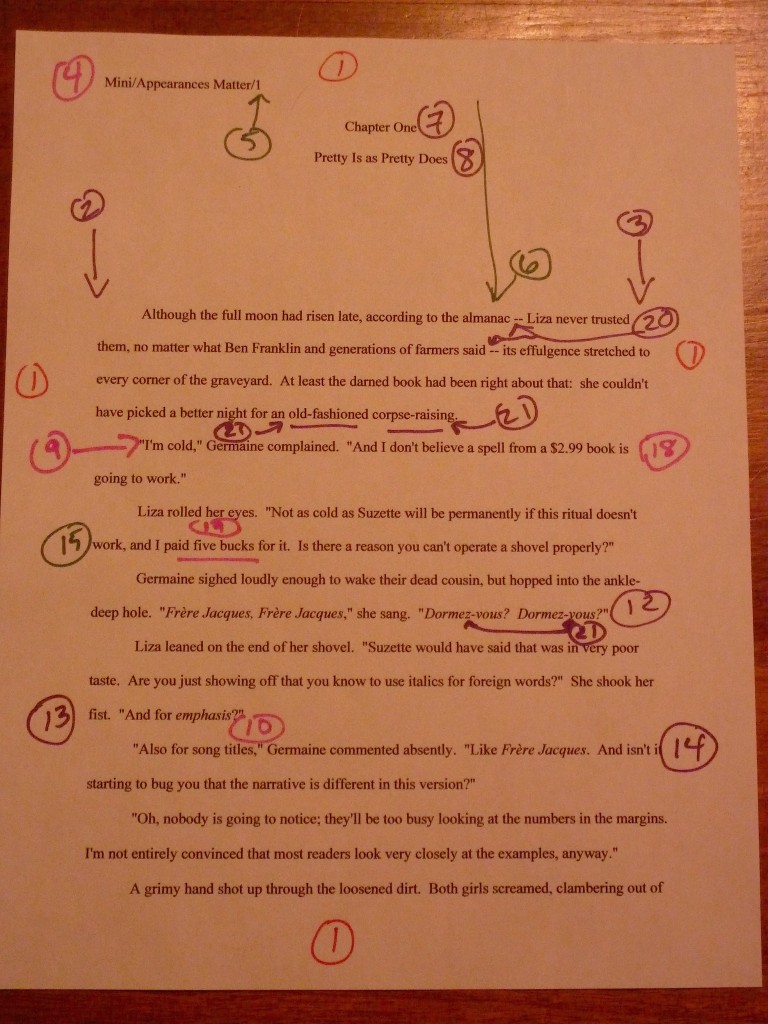

That’s a shame, really, as this type of typo/rule wobbling/dizzying confusion can distract the reader from the substance and style of the writing. To see how and why, take a gander at a sterling little passage in which this inadvertent eye-attractor abounds.

“All of this build up we’ve talked-about is starting to bug me,” Tyrone moaned, fruitlessly swiping at the table top buildup of wax at the drive in theatre. He’d been at it ever since he had signed-in on the sign in sheet. “I know she’s stepped-in to step up my game, but I’m tempted to pick-up my back pack and runaway through my backdoor to my backyard. ”

Hortense revved her pick up truck’s engine, the better to drive-through and thence to drive-in to the parking space. “That’s because Anne built-up your hopes in a much talked about run away attempt to backup her argument.”

At her lived in post at the drive through window, Ghislaine rolled her eyes over her game of pick up sticks. “Hey, lay-off. You mean build up; it’s before the argument, not after.”

“I can’t hear you,” Hortense shouted. “Let me head-on into this head in parking space.”

Ghislaine raised her voice before her tuned out coworker could tune-out her words. “I said that Anne’s tactics were built-in good faith. And I suspect that your problem with it isn’t the back door logic — it’s the run away pace.”

“Oh, pickup your spirits.” Hortense slammed the pick up truck’s backdoor behind her — a good trick, as she had previously e sitting in the driver’sseat. “We’re due to do-over a million dollars in business today. It’s time for us to make back up copies of our writing files, as Anne is perpetually urging us to do.”

Tyrone gave up on the tabletop so he could apply paste-on the back of some nearby construction paper. If only he’d known about these onerous duties before he’d signed-up! “Just give me time to back-up out of the room. I have lived-in too many places where people walk-in to built in walk in closets, and wham! The moment they’ve stepped-up, they’re trapped. ”

“Can we have a do over?” Ghislaine begged, glancing at the DO NOT ARGUE ABOUT GRAMMAR sign up above her head-on the ceiling. “None of us have time to wait in-line for in line skates to escape if we run overtime. At this rate, our as-yet-unnamed boss will walk in with that pasted on grin, take one look at the amount of over time we have marked on our time sheets, and we’ll be on the lay off list.”

Hortense walked-in to the aforementioned walk in closet. “If you’re so smart, you cut rate social analyst, is the loungewear where we lounge in our lounge where? I’d hate to cut-right through the rules-and-regulations.”

“Now you’re just being silly.” Tyrone stomped his foot. “I refuse to indulge in any more word misuse, and I ought to report you both for abuse of hyphens. Millicent will have stopped reading by the end of the first paragraph.”

A button down shirt flew out of the closet, landing on his face. “Don’t forget to button down to the very bottom,” Hortense called. “Ghisy, I’ll grabbing you a jacket with a burned out design, but only because you burned-out side all of that paper our boss had been hoarding.”

“I’m beginning to side with Millicent,” Tyrone muttered, buttoning-down his button down.

Okay, okay, so Millicent seldom sees so many birds of a feather flocking together (While I’m at it, you look mahvalous, you wild and crazy guy, and that’s hot. And had I mentioned that Millie, like virtually every professional reader, has come to hate clich?s with a passion most people reserve for rattlesnake bites, waiting in line at the D.M.V., and any form of criticism of their writing skills?) In queries and synopses, our gaffe du jour is be spotted traveling solo, often in summary statements like this:

At eight-years-old, Alphonse had already proven himself the greatest water polo player in Canada.

Or as its evil twin:

Alphonse was an eight year old boy with a passion for playing water polo.

Am I correct in assuming that if either of these sentences appeared before your bloodshot eyes in the course of an ordinary day’s reading, a hefty majority of you would simply shrug and read on? May I further presume that if at least a few of you noticed one or both of these sentences whilst reading your own query IN ITS ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD, as one does, you might either shrug again or not be certain how to revise it?

Do I hear you laughing, or is Tyrone at it again? “I know what the problem is, Anne!” experienced query- and synopsis-writers everywhere shout, chuckling. “Savvy writers everywhere know that in a query’s book description, it’s perfectly acceptable to introduce a character like this:

“Alphonse (8) has harbored a passion for playing water polo since before he could walk.

“As you will notice, it’s also in the present tense, as the norms of query book descriptions dictate. By the same token, the proper way to alert Millicent that a new character has just cropped up in a synopsis involves presenting his or her name in all capital letters the first time it appears, followed by his or her age in parentheses. While I’m sure you’d like to linger to admire our impeccable subject-object agreement in that last sentence, I’m sure readers new to synopsis-writing would like to see what the technique described in the first sentence of this paragraph would look like in print, so here it is:

“ALPHONSE (8) has harbored a passion for playing water polo since before he could walk — and now that a tragic Tonka Toy accident has left him temporarily unable to walk or swim, what is he going to do with his time?“

I’m impressed at how clearly you’ve managed to indicate what is and is not an example in your verbal statements, experienced ones, but we’re straying from the point a little, are we not? Not using parentheses to show a character’s age in a book description is hardly an instant-rejection offense, and eschewing the ALL CAPS (age) convention is unlikely to derail a well-constructed synopsis at submission time. (Sorry, lovers of absolute pronouncements: both of these are matters of style.)

Those are sophisticated critiques, however; I was hoping you would spot the basic errors here. Basically, the writer immortalizing Alphonse’s triumphs and tribulations has gotten the rule backwards. Those first two examples should have read like this:

At eight years old, Alphonse had already proven himself the greatest water polo player in Canada.

Alphonse was an eight-year-old boy with a passion for playing water polo.

Does that look right to you? If so, can you tell me why it looks right to you?

And no, Virginia, neither “Because you said it was right, Anne!” nor “I just know correct punctuation when I see it!” would constitute useful responses here. To hyphenate or not to hyphenate, that is the question.

The answer, I hope you will not be astonished to hear, depends upon the role the logically-connected words are playing in an individual sentence. The non-hyphenated version is a simple statement of fact: Alphonse is, we are told, eight years old. Or, to put it another way, in neither that last sentence or our first example does eight years old modify a noun.

In our second example, though, eight-year-old is acting as a compound adjective, modifying boy, right? The hyphens tell the reader that the entire phrase should be taken as a conceptual whole, then applied to the noun. If the writer wanted three distinct and unrelated adjectives to be applied to the noun, he should have separated them with commas.

The small, freckle-faced, and tenacious boy flung himself into the pool, eager to join the fray.

Are you wondering why I hyphenated freckle-faced? Glad you asked. The intended meaning arises from the combination of these two words: freckle-faced is describing the boy here. If I had wanted the reader to apply the two words independently to the noun, I could have separated them by commas, but it would be nonsensical to say the freckle, faced boy, right?

Applying the same set of principles to our old friend Pandora, then, we could legitimately say:

Pandora is an out-of-work diva.

The diva is a has-been; she is out of work.

Out-of-work has-been seeks singing opportunity.

Let’s talk about why. In the first sentence, the hyphens tell the reader that Pandora isn’t an out diva and an of diva and a work diva — she’s an out-of-work diva. In the second sentence, though, out of work does not modify diva; it stands alone. Has-been, however, stands together in Sentence #2: the hyphen transforms the two verbs into a single noun. In the third sentence, that same noun is modified by out-of-work.

Getting the hang of it? Okay, let’s gather our proofreading tools and revisit Tyrone, Hortense, and Ghislaine, a couple of paragraphs at a time.

“All of this build up we’ve talked-about is starting to bug me,” Tyrone moaned, fruitlessly swiping at the table top buildup of wax at the drive in theatre. He’d been at it ever since he had signed-in on the sign in sheet. “I know she’s stepped-in to step up my game, but I’m tempted to pick-up my back pack and runaway through my backdoor to my backyard. ”

Hortense revved her pick up truck’s engine, the better to drive-through and thence to drive-in to the parking space. “That’s because Anne built-up your hopes in a much talked about run away attempt to backup her argument.”

Some of that punctuation looked pretty strange to you, I hope. Let’s try applying the rules.

“All of this build-up we’ve talked about is starting to bug me,” Tyrone moaned, fruitlessly swiping at the tabletop build-up of wax at the drive-in theatre. He’d been at it ever since he had signed in on the sign-in sheet. “I know she’s stepped in to step up my game, but I’m tempted to pick up my backpack and run away through my back door to my back yard. ”

Hortense revved her pick-up truck’s engine, the better to drive through and thence to drive into the parking space. “That’s because Anne built up your hopes in a much-talked-about runaway attempt to back up her argument.”

All of those changes made sense, I hope. Since drive-in is used as a noun — twice, even — it takes a hyphen, but when the same words are operating as a verb plus a preposition (Hortense is driving into a parking space), a hyphen would just be confusing. Similarly, when Tyrone signed in, he’s performing the act of signing upon the sign-in sheet. He and his friends talked about the build-up, but Hortense uses much-talked-about to describe my runaway attempt. Here, back is modifying the nouns door and yard, but if we were talking about a backdoor argument or a backyard fence, the words would combine to form an adjective.

And a forest of hands sprouts out there in the ether. “But Anne, I notice that some of the compound adjectives are hyphenated, but some become single words. Why runaway, backpack, and backyard, but pick-up truck and sign-in sheet?”

Because English is a language of exceptions, that’s why. It’s all part of our rich and wonderful linguistic heritage.

Which is why, speaking of matters people standing on either side of the publishing wall often regard differently, it so often comes as a genuine shock to agents and editors when they meet an aspiring writer who says he doesn’t have time to read. To a writer, this may seem like a simple matter of time management — those of us in favor with the Muses don’t magically gain extra hours in the day, alas — but from the editorial side of the conversation, it sounds like a serious drawback to being a working writer. How on earth, the pros wonder, can a writer hope to become conversant with not only the stylistic norms and storytelling conventions of his chosen book category, but the ins and outs of our wildly diverse language, unless he reads a great deal?

While you’re weighing both sides of that potent issue, I’m going to slip the next set of uncorrected text in front of you. Where would you make changes?

At her lived in post at the drive through window, Ghislaine rolled her eyes over her game of pick up sticks. “Hey, lay-off. You mean build up; it’s before the argument, not after.”

“I can’t hear you,” Hortense shouted. “Let me head-on into this head in parking space.”

Ghislaine raised her voice before her tuned out coworker could tune-out her words. “I said that Anne’s tactics were built-in good faith. And I suspect that your problem with it isn’t the back door logic — it’s the run away pace.”

Have your edits firmly in mind? Compare them to this:

At her lived-in post at the drive-through window, Ghislaine rolled her eyes over her game of pick-up sticks. “Hey, lay off. You mean build-up; it’s before the argument, not after.”

“I can’t hear you,” Hortense shouted. “Let me head into this head-in parking space.”

Ghislaine raised her voice before her tuned-out coworker could tune out her words. “I said that Anne’s tactics were built in good faith. And I suspect that your problem with it isn’t the backdoor logic — it’s the runaway pace.”

How did you do? Admittedly, the result is still a bit awkward — and wasn’t it interesting how much more obvious the style shortcomings are now that the punctuation has been cleaned up? That’s the way it is with revision: lift off one layer of the onion, and another waits underneath.

In response to what half of you just thought: yes, polishing all of the relevant layers often does require repeated revision. Contrary to popular myth, most professional writing goes through multiple drafts before it hits print — and professional readers tend to be specifically trained to read for several different types of problem at the same time. So as tempting as it might be to conclude that if Millicent is distracted by offbeat punctuation, she might overlook, say, a characterization issue, it’s unlikely to work out that way in practice.

With that sobering reality in mind, let’s move on to the next section.

““Oh, pickup your spirits.” Hortense slammed the pick up truck’s backdoor behind her — a good trick, as she had previously e sitting in the driver’sseat. “We’re due to do-over a million dollars in business today. It’s time for us to make back up copies of our writing files, as Anne is perpetually urging us to do.”

Tyrone gave up on the tabletop so he could apply paste-on the back of some nearby construction paper. If only he’d known about these onerous duties before he’d signed-up! “Just give me time to back-up out of the room. I have lived-in too many places where people walk-in to built in walk in closets, and wham! The moment they’ve stepped-up, they’re trapped. “

I broke the excerpt there for a reason: did you happen to catch the unwarranted space between the final period and the quotation marks? A trifle hard to spot on a backlit screen, was it not? See why I’m always urging you to read your work IN HARD COPY and IN ITS ENTIRETY before you slip it under Millicent’s notoriously sharp-but-overworked eyes?

And see what I did there? Believe me, once you get into the compound adjectival phrase habit, it’s addictive.

I sense some of you continue to shake off the idea that proofing in hard copy (and preferably by reading your work OUT LOUD) is more productive than scanning it on a computer screen. Okay, doubters: did you notice the partially deleted word in that last excerpt’s second sentence? Did you spot it the first time you went through this scene, when I presented it as an unbroken run of dialogue?

The nit-picky stuff counts, folks. Here’s that passage again, with the small matters resolved. This time, I’m going to tighten the text a bit as well.

““Oh, pick up your spirits.” Hortense slammed the pick-up’s back door behind her — a good trick, as she had previously been sitting in the driver’s seat. “We’re due to do over a million dollars in business today. It’s time for us to make back-up copies of our writing files, as Anne is perpetually urging us to do.”

Tyrone gave up on the tabletop so he could apply paste to the back of some nearby construction paper. If only he’d known about these onerous duties before he’d signed up! “Just give me time to back out of the room. I have lived in too many places where people walk into built-in walk-in closets, and wham! They’re trapped. “

Still not precisely Shakespeare, but at least the punctuation is no longer screaming at Millicent, “Run away! Run away!” (And in case the three times this advice has already floated through the post today didn’t sink in, when was the last time you backed up your writing files? Do you have a recent back-up stored somewhere other than your home?)

The text is also no longer pointing out — and pretty vehemently, too — that if her boss did take on this manuscript, someone at the agency would have to be assigned to proofread every draft of it. That’s time-consuming, and to be blunt about it, not really the agent’s job. And while it is indeed the copyeditor’s job to catch typos before the book goes to press, generally speaking, agents and editors both routinely expect manuscripts to be thoroughly proofread before they first.

Which once again leads us to different expectations prevailing in each of the concentric circles surrounding publishing. To many, if not most, aspiring writers, the notion that they would be responsible for freeing their manuscripts of typos, checking the spelling, and making sure the grammar is impeccable seems, well, just a trifle crazy. Isn’t that what editors do?

From the professional reader’s side of the equation, though, it’s practically incomprehensible that any good writer would be willing to send out pages — or a query — before ascertaining that it was free of typos. Everyone makes ‘em, so why not set aside time to weed ‘em out? You want your writing to appear to its best advantage, right?

Hey, I’m walking you through this long exercise for a reason. Let’s take another stab at developing those proofreading skills.

“Can we have a do over?” Ghislaine begged, glancing at the DO NOT ARGUE ABOUT GRAMMAR sign up above her head-on the ceiling. “None of us have time to wait in-line for in line skates to escape if we run overtime. At this rate, our as-yet-unnamed boss will walk in with that pasted on grin, take one look at the amount of over time we have marked on our time sheets, and we’ll be on the lay off list.”

Did you catch the extra space in the last sentence, after the comma? Wouldn’t that have been easier to spot in hard copy?

Admit it: now that you’re concentrating upon it, the hyphen abuse is beginning to annoy you a bit, isn’t it? Congratulations: that means you are starting to read like a professional. You’ll pardon me, then, if I not only correct the punctuation this time around, but clear out some of the conceptual redundancy as well. While I’m at it, I’ll throw a logical follow-up question into the dialogue.

“Can we have a do-over?” Ghislaine begged, glancing at the DO NOT ARGUE ABOUT GRAMMAR sign on the ceiling. “None of us have time to wait in line for in-line skates.”

“What do skates have to do with anything?” Tyrone snapped.

“To escape if we run into overtime. At this rate, our boss will walk in with that pasted-on grin, take one look at our time sheets, and we’ll be on the lay-off list.”

Hey, just because we’re concentrating on the punctuation layer of the textual onion doesn’t mean we can’t also give a good scrub to some of the lower layers. Let’s keep peeling, shall we?

Hortense walked-in to the aforementioned walk in closet. “If you’re so smart, you cut rate social analyst, is the loungewear where we lounge in our lounge where? I’d hate to cut-right through the rules-and-regulations.”

“Now you’re just being silly.” Tyrone stomped his foot. “I refuse to indulge in any more word misuse, and I ought to report you both for abuse of hyphens. Millicent will have stopped reading by the end of the first paragraph.”

A button down shirt flew out of the closet, landing on his face. “Don’t forget to button down to the very bottom,” Hortense called. “Ghisy, I’ll grabbing you a jacket with a burned out design, but only because you burned-out side all of that paper our boss had been hoarding.”

“I’m beginning to side with Millicent,” Tyrone muttered, buttoning-down his button down.

Quite a bit to trim there, eh? Notice, please, how my initial desire to be cute by maximizing phrase repetition drags down the pace on subsequent readings. It’s quite common for a writer’s goals for a scene to change from draft to draft; to avoid ending up with a Frankenstein manuscript, inconsistently voiced due to multiple partial revisions, it’s a good idea to get in the habit of rereading every scene — chant it with me now, folks — IN ITS ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and, ideally, OUT LOUD after each revision.

Here’s how it might read after a switch in authorial agenda — and an increase of faith in the reader’s intelligence. If Hortense is able to walk into the closet and stay there for paragraphs on end, mightn’t the reader be trusted to pick up that it’s a walk-in closet?

Hortense vanished into the closet. “If you’re so smart, you cut-rate social analyst, is the lounge where we lounge in our loungewear? I’d hate to cut through the rules and regulations.”

“Has she gone nuts?” Tyrone whispered.

“That’s what you get,” Ghislaine muttered under her breath, “for complaining about Anne’s advice. She’s only trying to help writers like us identify patterns in our work, you know.”

A button-down shirt flew out of the closet, landing on his face. “I don’t think the build-up for Anne’s larger point is our greatest problem at the moment. Right now, I’m worried that she’s trapped us in a scene with a maniac.”

“Don’t forget to button your shirt to the very bottom,” Hortense called. “Ghisy, I’ll grab you a jacket.”

“Tremendous,” she called back. Scooting close to Tyrone, she added in an undertone, “If Anne doesn’t end the scene soon, we can always lock Hortense in the closet. That would force an abrupt end to the scene.”

“I vote for a more dramatic resolution.” He caught her in his arms. “Run away with me to Timbuktu.”

She kissed him enthusiastically. “Well, I didn’t see that coming in previous drafts”.

The moral, should you care to know it, is that a writer needn’t think of proofreading, much less revision, as a sterile, boring process in revisiting what’s already completely conceived. Every time you reread your own writing, be it in a manuscript draft or query, contest entry or synopsis, provides you with another opportunity to see what works and what doesn’t. Rather than clinging stubbornly to your initial vision for the scene, why not let the scene evolve, if it likes?

That’s hard for any part of a manuscript to do, though, if its writer tosses off an initial draft without going back to it from time to time. Particularly in a first book, storylines tend to alter as the writing progresses; narrative voices grow and change. Getting into the habit of proofreading can provide not only protection against the ravages of Millicent’s gimlet eye, but also make it easier to notice if one part of the manuscript to reflect different authorial goals and voice choices than other parts.

How’s the writer to know that if he hasn’t read his own book lately? Or, for that matter, his own query?

This is not, I suspect, the conclusion any of the fine people who suggested I examine hyphen abuse presumed my post would have. But that’s what keeps the conversation interesting: continually revisiting the same topics of common interest from fresh angles. Keep up the good work!

Enslaved By Ducks

Enslaved By Ducks Fowl Weather

Fowl Weather