Hello, campers —

My apologies to those of you who spent the afternoon and evening yesterday holding your breath, symbolically at least, in anticipation of my promised run-down on how to read, interpret, and follow contest entry rules. I honestly did mean to go into that last night — I’m all too aware that the postmark deadline for the William Faulkner/William Wisdom Literary Competition is this coming Tuesday — but health matters, alas, intervened. Long story. And if I have one rule I like to follow in life it’s not to give contest advice while on painkillers.

I’m still a bit groggy, so I’m going to cling to that excellent precept for at least a few hours longer. In the meantime, here is another of my favorite posts on how to write a 1-page synopsis. This one tackles the always-daunting challenge of trying to construct a synopsis for a multiple-perspective narrative.

Just in case anyone who might be thinking of entering a contest could use a few tips on the subject. Enjoy!

Still hanging in there, campers? I hope so, because we’ve been covering a whole lot of material in this expedited Synopsispalooza weekend: various lengths of novel synopsis on Saturday morning, an assortment of memoir synopses that evening, and this morning, different flavors of nonfiction synopsis. This evening, I had planned on blithely tossing off 1-, 3-, and 5-page versions of HAMLET told from multiple perspectives, as an aid to the many, many writers out there struggling with queries and submissions for multiple-protagonist novels — and then I noticed something disturbing.

As I often do when I’m about to revisit a topic, I went back and checked our last substantive Author! Author! discussion of diverse perspective choices. Upon scrolling through last April’s lively discussion of multiple-protagonist narratives (which began here, if you missed it), I realized that I had inadvertently left all of you perspective-switchers with a cliffhanger when I injured my back last spring: I devoted a post to writing a 1-page synopsis for a multiple-protagonist novel, fully intending — and, heaven help us, promising — that I would return to deal with 3- and 5-page synopses on the morrow.

You poor patient souls are still waiting, are you not? I’m so sorry — after my injury, I took a two-week hiatus from blogging, and I completely forgot about finishing the series. Then, to add insult to injury, I’ve been chattering about complex novel synopses under the misconception that those of you who followed last April’s discussion were already conversant with the basic strategy of synopsizing a multiple-protagonist novel.

Why on earth didn’t any of you patient waiters tell me that I had left you hanging? Who knows better than a writer juggling multiple perspectives that no single actor in a drama, however important, has access to the same sets of information that each other actor does?

No matter: I’m going to make it up to you perspective-jugglers, pronto. This post and the next will be entirely about writing a synopsis for a multiple-protagonist novel.

So that those new to the discussion will not have to play catch-up, this evening, with your permission, I would like to revisit the substance of that last post before I went silent, as it honestly does (in my humble opinion, at least) contain some awfully good guidelines for pulling off one of the more difficult tricks in the fiction synopsizer’s repertoire, boiling down a story told from several perspectives into a 1-page synopsis. To render this discussion more relevant to this weekend’s festivities, I shall be both updating it and pulling in examples from our favorite story, HAMLET.

You didn’t expect me to banish the melancholy fellow before the weekend was over, did you?

Let’s leap back into the wonderful world of the 1-page synopsis, then. I would not be going very far out on a limb, I suspect, in saying that virtually every working writer, whether aspiring or established — loathes having to construct synopses, and the tighter the length restriction, the more we hate ‘em. As a group, we just don’t like having to cram our complex plots into such short spaces, and who can blame us? Obviously, someone who believes 382 pages constituted the minimum necessary space to tell a story is not going to much enjoy reducing it to a single page.

Unfortunately, if one intends to be a published writer, particularly one who successfully places more than one manuscript with an agent or editor, there’s just no way around having to sit down and write a synopsis from time to time. The good news is that synopsis-writing is a learned skill, just as query-writing and pitching are. It’s going to be hard until you learn the ropes, but once you’ve been swinging around in the rigging for a while, you’re going to be able to shimmy up to the crow’s nest in no time.

Okay, so maybe that wasn’t the happiest metaphor in the world. But it is rather apt, as the bad news — you knew it was coming, right? — is that even those of us who can toss off a synopsis for an 800-page trilogy in an hour tend to turn pale at the prospect of penning a synopsis for a multiple-protagonist novel. It makes even the most harden synopsizer feel, well, treed.

Why? Well, our usual m.o. involves concentrating upon using the scant space to tell the protagonist’s (singular) story, establishing him as an interesting person in an interesting situation, pursuing interesting goals by overcoming interesting obstacles. Even if you happen to be dealing with a single protagonist, that prospect be quite daunting — but if you have chosen to juggle multiple protagonists, the mere thought of attempting to show each of their learning curves within a 1-page synopsis may well make you feel as if all of the air has been sucked out of your lungs.

Nice, deep breaths, everybody. It’s a tall order, but I assure you, it can be done. The synopsis-writing part, not just returning air to your lungs.

How? By clinging tenaciously to our general rule of thumb for querying a multiple-protagonist novel: the key lies in telling the story of the book, not of the individual protagonists.

Indeed, in a 1-page synopsis, you have no other option. So let’s spend the rest of this post talking about a few strategies for folding a multiple-protagonist novel into a 1-page synopsis. Not all of these will work for every storyline, but they will help you figure out what is and isn’t essential to include — and what will drive you completely insane if you insist upon presenting. Here goes.

1. Stick to the basics.

Let’s face it, a 1-page synopsis is only about three times the length of the average descriptive paragraph in a query letter. Basically, that gives you a paragraph to set up the premise, a paragraph to show how the conflict comes to a climax, and a paragraph to give some indication of how you’re going to resolve the plot.

Not a lot of room for character development, is it? The most you can hope to do in that space is tell the story with aplomb, cramming in enough unusual details to prompt Millicent the agency screener to murmur, “Hey, this story sounds fresh and potentially marketable — and my, is this ever unusually well-written for a single-page synopsis,” right?

To those of you who didn’t answer, “Right, by jingo!” right away: attempting to accomplish more in a single-page synopsis will drive you completely nuts. Reducing the plot to its most basic elements will not only save you a lot of headaches in coming up with a synopsis — it will usually yield more room to add individual flourishes than being more ambitious.

Admittedly, this is a tall order to pull off in a single page, even for a novel with a relatively simple plotline. For a manuscript where the fortunes of several at first seemingly unrelated characters cross and intertwine for hundreds of pages on end, it can seem at first impossible, unless you…

2. Tell the overall story of the book as a unified whole, rather than attempting to keep the various protagonists’ stories distinct.

This suggestion doesn’t come as a very great surprise, does it, at this late point in the weekend? Purely as a matter of space, the more protagonists featured in your manuscript, the more difficulty you may expect to have in cramming all of their stories into 20-odd lines of text. And from Millicent’s perspective, it isn’t really necessary: if her agency asks for a synopsis as short as a single page, it’s a safe bet that they’re not looking for a blow-by-blow of what happens to every major character.

Still not convinced? Okay, step into Millicent’s dainty slippers for a moment and consider which species of 1-page synopsis would be more likely to make her request the manuscript (or, in the case of a synopsis submitted with a partial, the rest of the manuscript). First, consider the common multiple-perspective strategy of turning the synopsis into a laundry list of what parts of the story are told from which characters’ perspectives:

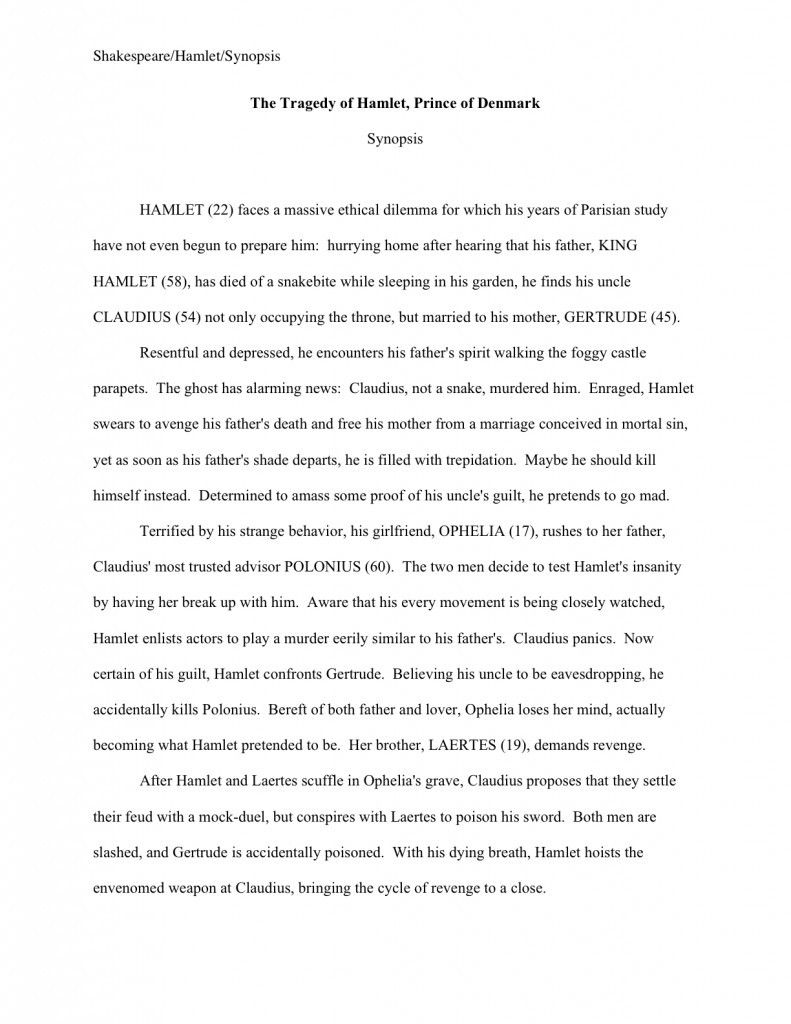

Poor Will is so busy accounting for all of his narrative perspectives that he does not have room to present much of the plot, does he? This structural choice forces him to cover the same plot elements over and over again. Compare this to the same story told as a single storyline, a smooth, coherent narrative that gives Millicent a sense of the actual plot of the book:

There really is no contest about which presents Shakespeare as the better novelist, is there? That’s no accident: remember, in a 1-page synopsis, the primary goal is not to produce a carbon-copy of the entire book, but to tell what the book is about in a manner that will prompt the reader to want to hear more.

So tell Millicent just that, as clearly as possible: show her what a good storyteller you are by regaling her with an entertaining story, rather than merely listing as many of the events in the book in the order they appear.

In other words: jettison the subplots. However intriguing and beautifully-written they may be, there’s just not room for them in the 1-page synopsis. Trust me, Millicent is not going to think the worse of your book for having to wait until she actually has the manuscript in her hand to find out every nuance of the plot — or, indeed, how many individual perspectives you have chosen to weave together into a beautifully rich and coherent whole.

That last paragraph stirred up as many fears as it calmed, didn’t it? “But Anne,” complexity-lovers everywhere cry out in anguish, “I wrote a complicated book because I feel it is an accurate reflection of the intricacies of real life. I realize that I must be brief in a 1-page synopsis, but I fear that if I stick purely to the basics, I will cut too much. How can I tell what is necessary to include and what is not?

Excellent question, complexity-huggers. The short answer is that in a 1-page synopsis, almost everything should be excluded except for the book’s central conflict, the primary characters involved with it, and what they have to gain or lose from it.

If you still fear that you have trimmed too much, try this classic editors’ trick: write up a basic overview of your storyline, then ask yourself: if a reader had no information about my book other than this synopsis, would the story make sense? Equally important, does the story sound like a good read?

Note, please, that I most emphatically did not suggest that you ask yourself whether the synopsis in your trembling hand was a particularly accurate representation of the narrative as it appears in the manuscript. Remember, what you’re going for here is a recognizable version of the story, not a substitute for reading your manuscript.

Which leads me to suggest…

3. Be open to the possibility that the best way to tell the story in your synopsis may not be the same way you’ve chosen to tell it in the manuscript.

Amazingly, rearranging the running order in the interests of story brevity is something that never even occurs to most struggling synopsizers to try. Yet in a multiple-perspective novel that skips around in time and space, as so many do, or one that contains many flashbacks, telling the overarching story simply and clearly may necessitate setting aside the novel’s actual order of events in favor of reverting to — gasp! — a straightforward chronological presentation of cause and effect.

Chronological order may not be your only option, however: consider organizing by theme, by a dominant plotline, or another structure that will enable you to present your complex story in an entertaining manner on a single page. Opting for clarity may well mean showing the story in logical order, rather than in the order the elements currently appear in the manuscript — yes, even if doing so necessitates leaping over those five chapters’ worth of subplot or ten of closely-observed character development.

Oh, stop hyperventilating. I’m not suggesting revising the book, just making your life easier while you’re trying to synopsize it. If you try to do too much here, you’ll only drive yourself into a Hamlet-like state of indecisive nuttiness: because no version can possibly be complete in this limited amount of space, no over-stuffed option will seem to be right.

For those of you still huffing indignantly into paper bags in a vain attempt to regularize your breathing again: believe me, #3 is in no way a commentary on the way you may have chosen to structure your novel — or, indeed, upon the complexity that tends to characterize the multiple-perspective novel. It’s a purely reflection of the fact that a 1-page synopsis is really, really short.

Besides, achieving clarity in a short piece and maintaining a reader’s interest over the course of several hundred pages can require different strategies. You can accept that, right?

I’m choosing to take that chorus of tearful sniffles for a yes. Let’s move on.

Storyline rearrangement is worth considering even if — brace yourselves; this is going to be an emotionally difficult one — the book itself relies upon not revealing certain facts in order to build suspense. Think about it strategically: if Millicent’s understanding what the story is about is dependent upon learning a piece of information that the reader currently doesn’t receive until page 258, what does a writer gain by not presenting that fact until the end of the synopsis — or not presenting it at all? Not suspense, usually.

And before any of you shoot your hands into the air, eager to assure me that you don’t want to give away your main plot twist in the synopsis, let me remind you that part of purpose of any fiction synopsis is to demonstrate that you can plot a book intriguingly, not just come up with a good premise. If that twist is integral to understanding the plot, it had better be in your synopsis.

But not necessarily in the same place it occupies in the manuscript’s running order. It may lacerate your heartstrings to the utmost to blurt out on line 3 of your synopsis the secret that Protagonist #5 doesn’t know until Chapter 27, but if Protagonists 1-4 know it from page 1, and Protagonists 6-13’s actions are purely motivated by that secret, it may well cut pages and pages of explanation from your synopsis to reveal it in the first paragraph of your 1-page synopsis.

Some of those sniffles have turned into shouts now, haven’t they? “But Anne, I don’t understand. You’ve said that I need to use even a synopsis as short as a single page to demonstrate my fine storytelling skills, but isn’t part of that virtuoso trick showing that I can handle suspense? If my current running order works to build suspense in the book, why should I bother to come up with another way to tell the story for the purposes of a synopsis that no one outside a few agencies and publishing houses will ever see?”

You needn’t bother, if you can manage to relate your storyline entertainingly in the order it appears in the book within a requested synopsis’ length restriction. If your 1-page synopsis effectively builds suspense, then alleviates it, heaven forfend that you should mess with it.

All I’m suggesting is that slavishly reflecting how suspense builds in a manuscript is often not the most effective way of making a story come across as suspenseful in a synopsis, especially a super-short one. Fidelity to running order in synopses is not rewarded, after all — it’s not as though Millicent is going to be screening your manuscript with the synopsis resting at her elbow, so she can check compulsively whether the latter reproduces every plot twist with absolute accuracy, just so she can try to trip you up.

In fact, meticulous cross-checking wouldn’t even serve her self-interest. Do you have any idea how much extra time that kind of comparison would add to her already-rushed screening day?

Instead of worrying about making the synopsis a shrunken replica of the book, concentrate upon making it a compelling road map. Try a couple of different running orders, then ask yourself about each: does this synopsis tell the plot of the book AS a story, building suspense and then relieving it? Do the events appear to follow logically upon one another? Is it clear where the climax falls? Or does it merely list plot events?

Or do those frown lines on your collective forehead indicate that you’re just worried about carving out more space to tell your story? That’s a perfectly reasonable concern. Let’s make a couple of easy cuts.

4. Don’t invest any of your scant page space in talking about narrative structure.

Again, this should sound familiar to those of you who have been following this Synopsispalooza. It’s not merely a waste of valuable sentences to include such English Lit class-type sentiments as the first protagonist is Evelyn, and her antagonist is Benjamin. Nor is it in your best interest to come right out and say, the theme of this book is…

Why? Long-time readers, chant it with me now: just as this kind of language would strike Millicent as odd in a query letter, industry types tend to react to this type of academic-speak as unprofessional in a synopsis.

Again you ask why? Veteran synopsis-writers, pull out your hymnals and sing along: because a good novel synopsis doesn’t talk about the book in the manner of an English department essay, but rather tells the story directly. Ideally, through the use of vivid imagery, interesting details, and presentation of a selected few important scenes.

Don’t believe me? I’m not entirely surprised: convinced that the proliferation of narrators is the single most interesting and marketable aspect of the novel — not true, if the manuscript is well-written — most perspective-juggling aspiring writers believe, wrongly, that a narrator-by-narrator approach is the only reasonable way to organize a synopsis.

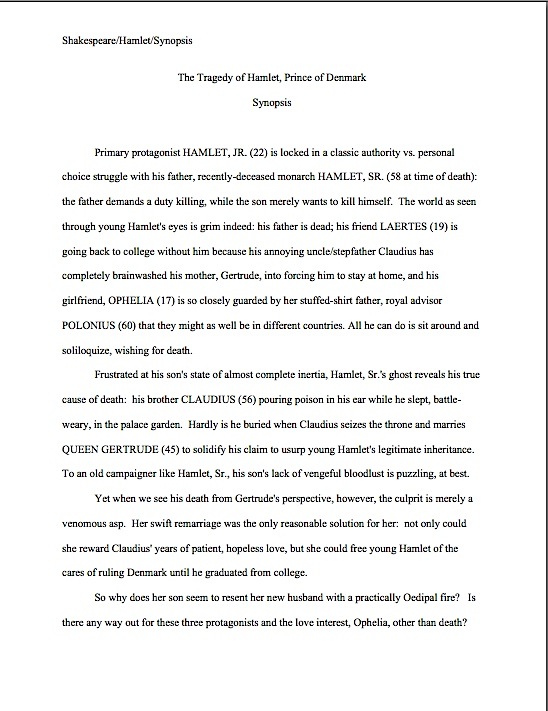

On the page, though, this seldom works well, especially in a 1-page synopsis. Compare the second example above with the following, a synopsis entirely devoted to analyzing the book as a critic might, rather than telling its story:

Not particularly effective at giving Millicent a sense of the overall plot, is it? Because the story is so complex and the individual characters’ perspectives so divergent, the seemingly simple task of setting out each in turn does not even result in an easily-comprehended description of the premise. Heck, the first three perspectives ran so long that our Will was forced to compress his fourth protagonist’s perspective into a partial sentence in the last paragraph.

Minimizing one or more narrators in an attempt to save space is a tactic Millicent and her aunt, Mehitabel the veteran literary contest judge, see all the time in synopses for multiple-protagonist novels, by the way. Protagonist-juggling writers frequently concentrate so hard on making the first-named protagonist bear the burden of the book’s primary premise that they just run out of room to deal with some of the others. In a synopsis that relies for its interest upon a diversity of perspectives, that’s a problem: as we saw above, an uneven presentation of points of view makes some look more important than others.

I sense the writers who love to work with multiple protagonists squirming in their chairs. “But Anne,” these experimental souls cry, “my novel has five different protagonists! I certainly don’t want to puzzle Millicent or end up crushing the last two or three into a single sentence at the bottom of the page, but it would be flatly misleading to pretend that my plot followed only one character. What should I do, just pick a couple randomly and let the rest be a surprise?”

Actually, you could, in a synopsis this short — which brings me back to another suggestion from earlier in this series:

5. Pick a protagonist and try presenting only that story arc in the 1-page synopsis.

This wouldn’t necessarily be my first choice for synopsizing a multiple-protagonist novel, but it’s just a defensible an option for a 1-page synopsis as for a descriptive paragraph or a pitch. As I pointed out above, the required format doesn’t always leave the humble synopsizer a whole lot of strategic wiggle room.

Concentrate on making it sound like a terrific story. You might even want to try writing a couple of versions, to see which protagonist’s storyline comes across as the best read.

Dishonest? Not at all — unless, of course, the character you ultimately select doesn’t appear in the first 50 pages of the book, or isn’t a major character at all. There’s no law, though, requiring that you give each protagonist equal time in the synopsis. In fact…

6. If you have more than two or three protagonists, don’t even try to introduce all of them in the 1-page synopsis.

Once again, this is a sensible response to an inescapable logistical problem: even if you spent a mere sentence on each of your nine protagonists, that might well up to half a page. And a half-page that looked more like a program for a play than a synopsis at that.

Remember, the goal here is brevity, not completeness, and the last thing you want to do is confuse our Millicent. Which is a very real possibility in a name-heavy synopsis, by the way: the more characters that appear on the page, the harder it will be for a swiftly-skimming pair of eyes to keep track of who is doing what to whom.

Even with all of those potential cuts, is compressing your narrative into a page still seeming like an impossible task? Don’t panic — there’s still one more wrench left in our writer’s tool belt.

7. Consider just making the 1-page synopsis a really strong, vivid introduction to the book’s premise and central conflict, rather than a vague summary of the entire plot.

Again, this wouldn’t be my first choice, even for a 1-page synopsis — I wouldn’t advise starting with this strategy before you’d tried a few of the others — but it is a recognized way of going about it. Not all of us will admit it, but many an agented writer has been known to toss together this kind of synopsis five minutes before a deadline. That’s a very good reason that we might elect to go this route: for the writer who has to throw together a very brief synopsis in a hurry, it’s undeniably quicker to write a pitch (which this style of synopsis is, yes?) than to take the time to make decisions about what is and is not essential to the plot.

Yes, yes, I know: I said quite distinctly farther up in this very post that the most fundamental difference between a descriptive paragraph and a synopsis is that the latter demonstrates the entire story arc. In a very complex plot, however, sketching out even the basic twists in a single page may result in flattening the story, rather than presenting it as a good read.

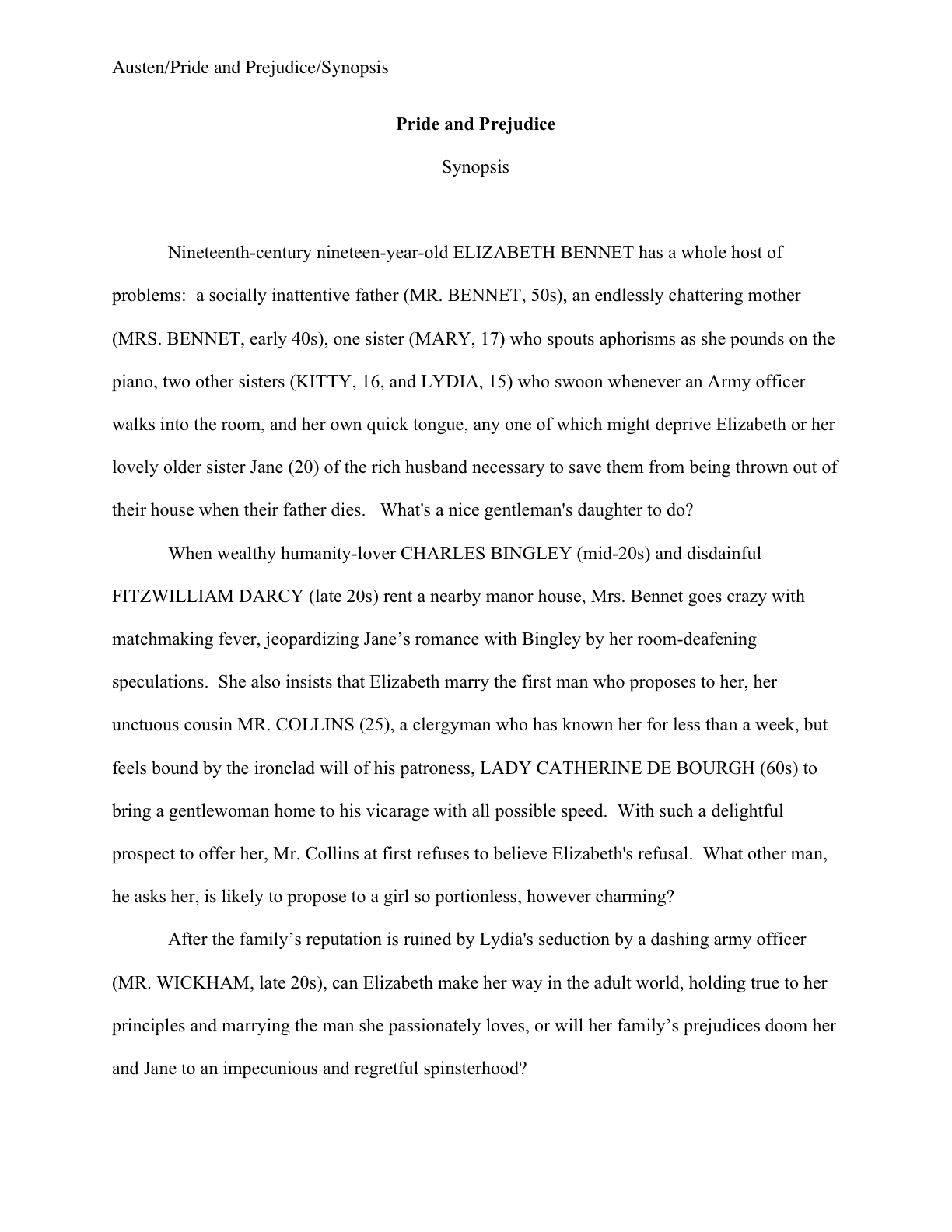

This can happen, incidentally, even if the synopsis is well-written. Compare, for instance, this limited-scope synopsis (which is neither for a genuinely multi-protagonist novel nor for HAMLET, but bear with me here; these are useful examples):

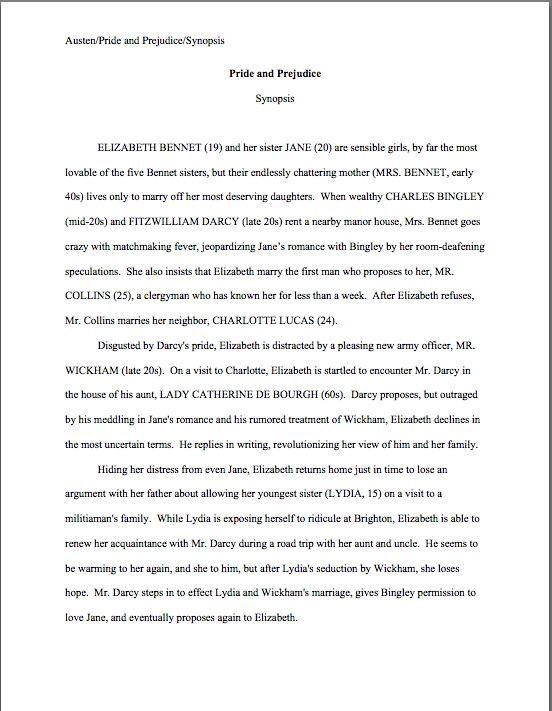

with one that covers the plot in more detail:

See how easy it is to lose track of what’s going on in that flurry of names and events? (And see, while we’re at it, proof that it is indeed possible to hit the highlights of a complicated plot within a single page? Practice, my dears, practice.) Again, a pitch-style synopsis wouldn’t be my first choice, but for a 1-page synopsis, it is a respectable last-ditch option.

An overstuffed 1-page synopsis often falls prey to another storytelling problem — one that the last example exhibits in spades but the one just before it avoids completely. Did you catch it?

If you instantly leapt to your feet, shouting, “Yes, Anne, I did — the second synopsis presents Elizabeth primarily as being acted-upon, while the first shows her as the primary mover and shaker of the plot!” give yourself seventeen gold stars for the day. (Hey, it’s been a long post.) Over-crammed synopses frequently make protagonists come across as — gasp! — passive.

And we all know how Millicent feels about that, do we not? Can you imagine how easy it would be to present Hamlet’s story as if he never budged an inch on his own steam throughout the entire story?

Because the 1-page synopsis is so short, and multiple-protagonist novels tend to feature so many different actors, the line between the acting and the acted-upon can very easily blur. If there is not a single character who appears to be moving the plot along, the various protagonists can start to seem to be buffeted about by the plot, rather than being the engines that drive it.

How might a savvy submitter side-step that impression? Well, several of the suggestions above might help. As might our last for the day.

8. If your draft synopsis makes one of your protagonists come across as passive, consider minimizing or eliminating that character from the synopsis altogether.

This is a particularly good idea if that protagonist in question happens to be a less prominent one — and yes, most multiple-protagonists do contain some hierarchy. Let’s face it, even in an evenly-structured multi-player narrative, most writers will tend to favor some perspectives over others, or at any rate give certain characters more power to drive the plot.

When in doubt, focus on the protagonist(s) closest to the central conflicts of the book. Please don’t feel as if you’re slighting anyone you cut — many a character who is perfectly charming on the manuscript page, contributing a much-needed alternate perspective, turns out to be distracting in a brief synopsis.

Keep up the good work!