I could blame my last few days of visible silence on having polished off the task I set for myself in this series: we did count down to the entry deadline for a major literary contest, and I did manage to talk about the major technical bugbears that dog contest entries. I could also pat myself on the bat for giving those of you that did enter that contest a few days to recover afterward. Let’s face it, while entering a writing contest is one of the best ways for an aspiring writer with no previous publications to garner ECQLC (Eye-Catching Query Letter Candy), it’s also exhausting, demanding, and more than a little stressful to prepare an entry well.

Oh, those are both true, and both pretty good justifications for not posting for a few days. But the fact is, I’ve just been too depressed to blog. It being your humble correspondent, my reasons for tumbling down the great blue hole that writers know so well were almost entirely literary.

How so, you ask, backing away because you fear whatever it is might be catching? Well, over the past week, I’ve had occasion to observe first-hand a couple of dozen authors (first-time, established, old hand) promoting their books. Or at least trying to promote them. Surprisingly often, that takes the form of contacting someone like me.

Not a bad choice: my family’s been in and out of publishing since the 1920s, and substantial portions of my kith and kin were writing political fiction in the 1930s and 40s, or science fiction and fantasy in the 1950s and 1960s, both now-recognized genres that nice, literate people used to pretend in public that they didn’t read, then devour in private. Just sitting back and assuming one’s publisher would take care of book sales was a luxury these authors did not have. As a direct and, I think, entirely laudable result, I can’t remember a time in my life when I didn’t know that no matter how good a publishing house’s marketing department might be, it was ultimately up to the author to convince at least a few readers to buy a book.

And I have distinct memories of events seen through the bars of my playpen. That being literarily gifted does not excuse one from attending to the business part of the publishing business has always seemed as much a fact of life to me as gravity making things fall down instead of up.

Imagine my dismay, then, when a very good author of a decade’s worth of exceptionally fine novels asked me for advice on how to promote her soon-to-be-released book. Immediately, I began churning out suggestions for online promotion, as is my wont.

She stopped me after three low-cost promotional ideas. “Oh, I can’t do any of that. I would look desperate.”

“Um, Ambrosia?” I asked, for Ambrosia was not her name but an undetectable pseudonym. “Have you not noticed that pretty much everyone with a book out is just a touch desperate these days? Or are you under the impression that people who read don’t understand that authors would like to make a living at it, and that making a living at it is dependent upon readers buying books?”

She lit up at what I can only guess in retrospect were a few non-consecutive words in that last sentence. “Yes, exactly — my last book did not sell very well, and I’m worried about the next. If only the author weren’t completely helpless in this situation!”

Was it heartless of me to burst into peals of laughter, campers? I’d just given Ambrosia at least a month’s worth of ways not to be helpless, promotional moves that would have cost him nothing but time and energy. To add icing to what was already a mighty fine cake, she’s a friend, so this was free advice, too. (Oh, you thought Author! Author! was the only place I couldn’t stop myself from holding forth?) Yet here she was, falling all over herself not to take it.

Now, I could have just given up. It’s the golden age of authorial outreach, after all; it’s now more or less expected that an author will get actively involved in online promotion. Yet I get Ambrosia’s point of view: she started writing back in the days when it was in fact considered a bit gauche for a high literary fiction author to do anything but wait to see if the reviews were good and smile graciously at the signings her publisher’s hardworking marketing department set up for her.

Of course, I talked her down — what do you take me for? After the requisite half an hour of disbelieving what I was telling her, followed by the equally requisite ten minutes of acting as though the new realities of authorship were entirely my fault, she hung up the phone a sadder but wiser pseudonym. She might even take some of my advice.

This kind of exchange is, alas, far too common these days for it alone to have depressed me — although it does make me sad to see a good author not understand how reaching her audience has changed over the last ten years. Especially when I’m relatively certain that her assigned publicist (a terrific lady who definitely knows the current market and is enough of a boon to her publishing house that if she hadn’t specifically forbidden me to name her on my blog, lest incoming authors stampede her office, would now praise to the skies) had already tried to get Ambrosia to do some of the things I was suggesting. I did suggest that she tell her that she, like the overwhelming majority of authors new to online promotion, had been thinking of her Facebook and Twitter accounts as if they were book signings: if it’s there, the fans will just show up, right?

More on that half-true authorial presumption in a moment. I want to tell you about something that happened the next day.

I was enjoying a nice cup of tea with Trevor, another author friend and someone who also has a book in the spring’s new offerings list. As a shameless friend (and every good writer needs many), I naturally had bought a copy of his book the nanosecond it came out, because those gratis copies his publisher gave him were intended for promotion, not to hand out to kith and/or kin. (You’ve already started disabusing your friends and neighbors on that point, right? The best way to help an author is to buy his book, and the sooner your Aunt Sadie accepts that, the happier you’ll be when you have a book out. Tell her you’ll be happy to sign it.) I also, although Trevor did not think to ask his shameless friends to do this, cranked out a review and posted it on Amazon and a few other sites.

“Oh, and before I forget,” I told him, “I noticed mine is the only review on Powell’s and B & N. A single reader review can come across as a fluke, so you’re going to want to ask a few friends to post there, too, as well as Amazon.”

As a fan of the gentle art of comedy, I can tell you that his subsequent spit-take was flawlessly executed. After he had rushed over to the nearest table with back-up napkins, apologizing profusely, he returned to help me sop up the remains of our shared cookie plate. “How did you know,” he hissed as soon as our neighbors stopped staring at us, “that I’d recruited any reviews at all?”

“Experience? And the fact that nobody but your mother and the second reviewer has ever called you Trevvie?”

Okay, so I made up that last part to amuse you; his mother’s review was far subtler than that. I did hasten to assure him, though, that he had been smart to ask his relatives, friends, friends of relatives, and relatives of friends to read the book and post reviews. It’s a fairly standard practice now, if only to get the ball rolling during the inevitable lag between the professional reviews (which sometimes appear quite a bit before the book’s release) and readers who do not know the author personally having read the book.

He did not, therefore, suffer from either a shortage of helpful friends (thanks, Mom!) or qualms about accepting their help. Subsequent conversation revealed, however, that he had been squeamish about asking those very same people to post a simple hey, my son/college roommate/coworker in his hated day job had a book out — and here’s a link! on their already-extant social media pages. Or — and this made me choke on my fresh cup of tea — to post such a request on his Facebook fan page.

I’ll spare you the conversation that followed, as well as an enumeration of all the café staff and habitués that pounded me on the back in turn. Suffice it to say that I was surprised: as far as any of us knew, the people who read his fanpage were, in fact, fans. Why wouldn’t people who already enjoyed his writing want to help him promote his book, especially when he could make it so easy for them by posting a link with the request?

Since we were already the pariahs of the teashop, he had no qualms about answering that last question out loud: because most of the people kind enough to have hit the LIKE button on his fanpage were — you saw this coming, didn’t you? — precisely the same generous souls he had asked to write reviews. Since he’d already asked a favor — two, since he’d asked most of them to take pity on him and hit LIKE — he felt funny about asking another.

“I guess that means that you wouldn’t be comfortable asking them to turn your book cover-outward anytime they’re in a bookstore,” I said. “A browser’s much more likely to pick it up.”

As with Ambrosia, what made me sad about this exchange (other than that last suggestion’s practically driving Trevor to tears) was not that he was too shy to make these relatively simple requests of people he already knew loved him, but that he was apparently unaware that it would behoove him to reach out to potential readers he did not already know. Indeed, he argued with me on that point, during that requisite ten minutes of target practice aimed at the messenger I mentioned earlier: “If you don’t know,” he sniffed, as though my suggestions were terribly lowbrow, “nothing makes people more uncomfortable than a sales pitch. If the reviews are good, then the book will sell.”

“Not always,” I said gently, bracing myself for the next barrage. “And not if your potential readers don’t know about them. All I’m suggesting is that you ask your established readership to offer their friends some encouragement to follow a link to those reviews.”

Again, I’ll spare you the subsequent debate; I’m sure you clever, imaginative souls can flesh it out unassisted. To get you started: apparently, it’s cynical and literature-hating to believe not only that readers will not buy a book if they have never heard of it, but that posting something — anything — online won’t instantly attract millions of looks. Call me zany — and Trevor did, several times — but I believe that signposts are helpful in getting people from Point A to Point B.

“But you’re a blogger,” he accused, in a tone that implied the term was synonymous with convicted poisoner of dozens; need I mention that his marketing department has been urging him fruitlessly for years to start blogging? “You of all people know that if you post it, they will come.”

“Ah, but I’ve been blogging for nearly seven years.” I did not add that when I started blogging, my memoir’s scheduled release was within six months. “And I’ve only had a Facebook fanpage for about a year. Come to think of it, I don’t think I’ve ever asked my blog’s readership if they would be kind and generous enough to follow a link there and press the LIKE button; I shall have to rectify that sometime soon. It would certainly make my agent happy.”

“Oh, come on,” Trevor said. “You know there’s no way to do that gracefully.”

I swear I did not that last observation up. Trevor has promised to keep an eye on my fanpage‘s likes over the next few weeks. Would you mind terribly helping me convince him that it would be worth his while to make a polite request of people who already know and appreciate his writing by following that link and LIKE-ing my page?

Again, though, I do understand why he feels overwhelmed: there’s just a lot more for an author to do these days. My upbringing leads me to believe that’s a good thing — what makes one feel more helpless than not being able to do anything to improve one’s prospects? — but I do realize that Trevor, like the vast majority of aspiring writers, began writing under the assumption that if he wrote a good enough book, it actually would sell itself. Or at least that the fine folks employed by his publishing house would do it for him, which, in terms of effort expenditure, amounts to very much the same thing.

Before I leave you to ponder all of this vis-à-vis your own current and future books and get back to talking about ECQLC-generating contest entries — oh, you thought I had abandoned my teaching goals for the day? — I would like to share the final literary depressive factor of the week. It will amuse you, Trevor, to see that it was an event a publisher had arranged in order to promote not just one, but several quite good books. It was a group signing at a large, well-stocked bookstore.

Naturally, I hied myself hence: I know one of the authors, and one of the nicest things a shameless friend can do to help an author is to help swell the ranks at a book signing. (If one wants to be a genuine peach, one ostentatiously buys the book at the signing, to encourage others to do so; of course I did.) To make it an even more efficient use of my literary booster time, another of the authors on the dais writes in the same book category I do — and if I have to explain to you why it’s in a writer’s best interest to make sure her chosen book category sells well, or why one of the best ways to assure editors to keep publishing writing in that category is to buy those books, and regularly, well, I can only wring my hands and wonder where I went wrong in the past seven years.

Hying myself hence was no easy task, however, because one of the local arts-oriented websites had misreported the time it started. Another paper, a free one that’s the only print paper to list author readings habitually, had recommended the signing and listed the correct time, but had referred readers to another page of the publication for an explanation of why it would be worth their time to attend. There was no mention of the event on the other page.

No way to anticipate any of that, of course, but those were not the only attendance-discouraging factors. The event had been scheduled for the same time as the opening of the Seattle International Film Festival — and about a block and a half away. Parking was nonexistent. John Irving was also speaking across town that night; even I thought twice about which event to attend.

Considering everything, then, the event’s organizers should be quite proud of themselves: about 25 people showed up. (And in response to those of you who just clutched your chests: that’s quite a respectable turn-out for a book signing; it’s not all that uncommon for authors to end up spending an hour or two addressing one fan, two bookstore employees, and a roomful of empty chairs.) They also had piles of the various authors’ books readily available — well done! — and had obviously collected a group of intelligent, articulate, interesting authors.

Most of whom looked positively terrified throughout the entire event. A few made a substantive effort to interact with the audience, but not all of them participated in answering questions. A couple of them did not even try to have conversations with the fans handing them books. The sweet 12-year-old who’d lugged his copies of every book one of the authors had ever written was, to say the least, a little surprised that his hero talked to one of the other authors while signing his way through the stack.

Sensing a pattern here, or at least a similarity to Ambrosia and Trevor’s promotional attempts? No? Okay, let me fill in a few more depressing details.

It’s fairly standard at book signings for authors to read from their work…and do I even need to finish this sentence? Not a word. It’s also usual for the authors, or at any rate the person introducing them, to give a short overview of what the books they would like to sign are about. Nor a murmur. Why would they? Everyone in the room had already read those books, right?

Anyone but me see this as a problematic assumption at an event devoted to selling the books in question? But it’s understandable, in the light of Trevor and Ambrosia: since the books would of course sell themselves, one shows up to a book signing to reward those that have already read them, not to try to coax new readers. If I have to explain why that attitude might be a trifle self-defeating at an event featuring more than one author…again, where did I go wrong in raising you?

In the unlikely event that I am now or have ever been too subtle on this point: book signings and readings are not about bolstering the authorial ego; they’re about selling books. They’re performances.

Speaking of which, as if all of that were not enough to keep nearby browsers from dropping by to see what was going on — none of them did, although that’s pretty standard for author signings, too — not all of the authors were audible to the back row of the audience when they did speak. Nor did the moderator repeat questions, so everyone there could hear them.

Now, I’ve given talks in that particular room of that particular bookstore, so I would be the first to admit that the acoustics are terrible. The bookstore’s wonderful staff admits it, too; as I can tell you from experience, they routinely offer to set up microphones for occasions like this. So if chatterers wandering around the shelves were sometimes more audible than some of the authors, I’m disinclined to blame the bookstore’s acoustics.

Will anyone accuse me of being cynical if I suggest that it might be prudent for authors to arrive a little early check out the acoustics at any venue at which they plan to speak? Or to rack up a little practice in being charming to readers nice enough to want to have their books signed?

Or at least not to be surprised when only 7 of those 25 audience members bought books?

To be clear, I’m not saying any of this to be critical of those authors, the bookstore’s staff, or the publisher that set up the event. (Although personally, I might have checked the local events listings before I set it up.) I’m just saying that it might have gone better had everyone concerned thought about it from the attendee’s point of view. Especially that delightful 12-year-old: should I have been the only adult in the room who asked him why he loved that armload of books?

I know: hands up if you have ever been that kid. Can you imagine how thrilled he would have been had his favorite author taken the time to treat their interaction as anything but routine fan maintenance? It’s not hard to make a devoted reader feel special, especially one that staggers into an event like this with a dozen hardcover books.

Lest anyone suggest that since this bright, articulate kid had already bought the books in question, the event was not really aimed at him: that kid goes to school; that kid goes online; that kid has friends and siblings that read (his older sister staggered under her own armload of books). Wouldn’t it actually have been a great way to get the word out the author’s new book to treat him in a way that will make the boy rush to tell everyone he knows about how nice his idol was to him? And, since this was a group event, wouldn’t it have helped everybody if the author had made a few recommendations for future reading?

That’s why, in case any of you had been wondering, I was so adamant throughout last winter’s Queryfest that it’s in a writer’s best interest to give some pretty serious thought to who her target reader is. I could have told the author in question that smart 12-year-olds read his work; after talking to the fan, I can tell you now that there’s a better than even chance this 12-year-old is going to grow up to be a writer. And that means that he’s going to be looking to his favorite authors for guidance about how to act while promoting a book.

Oh, that hadn’t occurred to you? It probably didn’t occur to the author, either, but it could not have been more obvious to me. I grew up watching devoted readers toting stacks of books into science fiction conventions and book signings, so my relatives and friends could sign them. An inspired fan has a light in her eye, a glow to her face; it’s visible from across the room.

So am I cynical or literature-loving to believe that creating a positive experience for that reader at a signing is an essential part of the author’s job? Or that the opportunity to do so is something for which a savvy author should be exceedingly grateful?

Can you wonder now that I left depressed? Not all of the authors missed those fundamentals, but enough did that even I, who loves good writing enough to have devoted my life to it, wondered if I should have attended the event at all.

I have not asked my friend on the dais (who, I am delighted to report, interacted with her fans exceedingly well) if her colleagues, the bookstore, or the publisher were disappointed by the sales generated by the event; my guess is that they were not. Lackluster sales at readings and signings are one of the reasons many publishers sponsor fewer these days. It’s common to blame the fans for that.

Just something to ponder. If even one of you finds yourself facing an eager 12-year-old fan across a signing table and decides to make not only his day, but change the course of his life by taking a sincere interest in him, I will indeed feel that I have done all I can here.

Back to business — and yes, I’m going to talk about contests now, because I know that some of you tuned in for it. It’s important not to disappoint one’s readership, after all.

For the sake of those of you who tuned in because you’re in the habit of tuning in, though, bless you. I’ll keep it relatively brief. I wouldn’t want to eat into any time you were planning to devote to liking things on Facebook this weekend, after all.

As I pointed out earlier in this series, although marketability is surprisingly seldom listed as one of the judging criteria in contest rules, it is very, very frequently in the judges’ minds when they read — which means, all too frequently, that if you offend their sensibilities, they will conclude that your work isn’t marketable enough to make it to the finalist round. Or at least not enough so to please current market tastes.

I introduced the change of subject too abruptly, didn’t I? As soon as I typed it, I heard the moods that had risen again after my downer of an opening over deflate hissingly once again. Sorry about that; I’m afraid that there’s just no upbeat way to shatter the ubiquitous misconception that the only thing a literary contest judge ever considers is the inherent quality of the writing in the entry.

But as we’ve been discussing, what constitutes good writing at one time — or in one book category — is not necessarily what was or will be considered good writing at all times or in all settings. The literary market is notoriously volatile. Then, too, contest judges, like agents, editors, and any other reader, harbor personal tastes. We would all have different takes on what makes a book good, what sentiments are acceptable, and, perhaps most for the sake of contest entry, different ideas of what is marketable. Or even of what fits comfortably under a particular contest category.

However, there are a few simple ways you can minimize the possibility of raising red flags before the eyes of our old pal, Mehitabel the veteran contest judge. Perhaps not entirely surprisingly, quite a few of these pitfalls tend to turn up on pet peeve lists in agencies and publishing houses as well.

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #1: avoid clichés like the proverbial plague.

Oh, you may laugh, but clichés are amazingly common in contest entries, for some reason I have never understood — unless it is simply that clichés become clichés because they are common. It puzzles Mehitabel, too, because isn’t the goal of entering writing in a contest to show how you phrase things and conceive of stories, not how people tend to phrase things in general or how TV shows present storylines?

You really do want to show contest judges phraseology and situations they’ve never seen before, so try to steer clear of catchphrases (I know, right?), stock characters (Here’s your badge back, rookie-who-cannot-follow-the-rules, and here’s your new partner. He’s supposed to retire next month!), tried-and-true plot twists (You don’t mean — you’re my FATHER?!?), and anything, but anything, that you’re tempted to include just because it’s cultural shorthand for how a particular group of people act (“Whatever!” said the teenager, rolling her eyes.

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #2: minimize current pop culture references.

In general, you should avoid pop culture references in contest entries, except as indicators of time and place. Not only do they tend to be clichés (Hey, Betty Sue, want to go down to the malt shop and sock-hop to the latest Chuck Berry record in your poodle skirt?), but in a contest entry, they take up space that could be used for more original description.

Yes, yes, I know: dropping in the odd Bee Gees reference to a story set in 1976 feels like verisimilitude. It can be. But you wouldn’t believe how often Mehitabel sees entries that seem intent upon proving that every single soul on the planet liked the same music in 1976.

Current cultural references run all of these risks, but they suffer from an additional problem: even the most optimistic judge would be aware that an unpublished work entered in a contest could not possibly be in print in less than two years from now — and thus the reference in question needs to be able to age at least that long.

In answer to that collective gasp I just heard from those of you new to the publishing world: books don’t typically hit the shelves for at least a year after the publication contract is signed — and often more than that. Print queues are long, and before a first-time author’s work enters one, the acquiring editor often requests changes in the text.

That’s not counting the time the agent spends shopping the book around first, of course. And that clock doesn’t even begin to tick until after the writer has found an agent for the book in the first place.

So even if a cultural reference is white-hot right now, it’s probably going to be dated by the time it hits the shelves. For instance, do you really think that anyone will know in five years who Paris Hilton is, or why she was famous? (I’m not too sure about the latter now.)

Also, writers tend to underestimate how closely such references tend to be tied to specific eras, regions, and even television watching habits. Which brings me to…

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #3: never assume that the judge will share your worldview.

You would be astonished at how often the writer’s age — or, at any rate, generational identification — is perfectly obvious from the cultural references used in a contest entry. Ditto with political views, or lack thereof, sex, gender (not the same thing), socioeconomic status…

All of that is fine, especially for a memoir or first-person fiction, but you need to be careful that the narrative does not assume that the judges determining whether your work makes it to the finalist round share your background in any way. Why? Well, nothing falls flatter than a joke that the reader doesn’t get, unless it’s a shared assumption that’s shared by a group to which the reader does not happen to belong.

It’s exceedingly common for contest entrants to assume (apparently) that the judges assessing their work are share their age group, sex, sexual orientation, views on foreign policy, you name it. So much so that they tend to leave necessary references unexplained.

And this can leave a Mehitabel who does not happen to be like the entrant somewhat perplexed. Make sure that your story or argument could be followed by any English-reading individual without constant resort to the encyclopedia or MTV.

Did you catch the problem with that last sentence? It shows my age.

That’s right: I’m old enough to remember when MTV was entirely devoted to music videos. Seems strange now, doesn’t it? I’m also old enough (but barely), to shake my head over the fact that if Mehitabel is of the Internet generation, she may never have touched a hard-copy encyclopedia.

It could easily go the other way, of course — and probably will, in a contest entry. (Most literary contests require some writing or publishing background before allowing someone to judge.) It’s not beyond belief that Mehitabel will never have seen a music video. Or know what Glee is, beyond a good mood.

The best way to steer clear of potential problems: get feedback on your entry from a few readers of different backgrounds than your own, so you can weed out references that do not work universally. Recognize that your point of view is, in fact, a point of view, and as such, naturally requires elucidation in order to be accessible to all readers.

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #4: if you are taking on social or political issues, show respect for points of views other than yours.

This is really a corollary of the last. If you’re going to perform social analysis of any sort, it’s a very, very poor idea to assume that the contest judge will already agree with you — especially if everyone you know agrees with you on a particular point. A stray snide comment can cost you big time on a rating sheet.

I’m not suggesting that you iron out your personal beliefs to make them appear mainstream — contest judges tend to be smart people, ones who understand that the world is a pretty darned complex place. But it’s worth bearing in mind that Mehitabel may well get her news from sources different than yours; her view of current events might well make your jaw drop, and vice-versa.

And that’s a problem, because an amazingly high percentage of contest entries, particularly in the nonfiction categories, are polemics. Novels often they use the argumentative tactics of verbal speech. But while treating the arguments of those who disagree with dear self as inherently ridiculous can work aloud (although it’s certainly not the best way to win friends and influence people, in my experience), they tend to work less well on paper.

So approach your potential readers with respect, and keep sneering at those who disagree with you to a minimum. And watch your tone, especially in nonfiction entries, lest you become so carried away in making your case that you forget that a member of your honorable opposition may well be judging your work.

This is a circumstance, like so many others, where politeness pays well. Your mother was right about that, you know.

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #5: recognize going in that you have absolutely no control over how an individual judge will respond to your work. All you can control is how you present it.

Trust me, you will be a much, much happier contest entrant if you accept that you cannot control who will read your work after you enter it into a contest. Sometimes, you’re just unlucky. If your romance novel about an airline pilot happens to fall onto the desk of someone who has recently experienced major turbulence and resented it, there’s really nothing you can do about it.

Those of you trying to land an agent recognize this dilemma, right? It’s precisely the same one queries and submissions to agencies face.

To revert to my favorite gratuitous piece of bad luck: if Millicent the agency screener has scalded her tongue on a too-hot latté immediately prior to opening your submission, chances are that she’s going to be in a bad mood when she reads it. And there’s absolutely nothing you can do about that.

The same holds true for a contest entry. Ultimately, you can have no control over whether Mehitabel has had a flat tire on the morning she reads your entry, any more than you can control if she has just broken up with her husband, or has just won the lottery.

All you can do approach the process with a sense of professionalism: make your work the best it can be, and keep sending it out until you find the reader who gets it. Which brings me to…

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #6: don’t expect a single contest entry to make your writing career all by itself.

Okay, so this one is really more about your happiness than the judges’, but do try to avoid hanging all of your hopes on a single contest. That’s giving way too much power to a single, unknown contest Mehitabel.

Yes, even if there is only one contest in your part of the world for your kind of writing. Check elsewhere.

And, of course, keep querying agents, magazines, and small presses while your work is entered in a contest. (No, this is not a contest rule violation, in most cases: contests almost universally require that a entry not be published prior to the entry date. You’re perfectly free to keep submitting after you enter it — and to enter the same work in as many contests as you choose.)

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #7: be alert for subtle clues about style expectations that may not match your writing.

As I mentioned earlier in this series, if a contest does not have a track record of rewarding your type of work, it’s just not a good idea to make it your single entry for the year. You might even want to think twice about entering that contest at all.

Yes, even if the rules leave open the possibility that your kind of work can in theory win For instance, a certain contest in my area has a Mainstream Fiction category that also accepts literary fiction — and in many years, has accepted genre as well.

Care to guess how often writing that wasn’t explicitly literary has won in this category? Here’s a hint: for many years, the judges had a strong preference for work containing lots and lots of semicolons.

Still unsure? Well, here’s another hint: in recent years, the category description had devoted four paragraphs to defining literary fiction. Including a paragraph specifying that they meant the kind of work that tended to win the Nobel Prize, the Booker Award, the Pulitzer…

In case that didn’t shake up those of you considering entering an honestly mainstream work, I should also add: there have been years in which there were only four paragraphs in the description.

This is yet another reason — in case, you know, you needed more — to read not only the contest rules very carefully, but the rest of a contest’s website as well. Skim a little too quickly, and you may not catch that contest organizers have given a hint to what kinds of work they want to see.

You know, something subtle, like implying that they expect their contest winners to be future runners-up for the Pulitzer.

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #8: be alert for subtle clues about content.

Most literary contests will break down judging categories by writing style and book category, rather than content, but a surprising number of them harbor content preferences. They tend to be fairly upfront about them, too., referring to them either overtly (in defining the categories) or covertly (in defining winning criteria for the judges).

This is particularly true in short story and essay competitions, I notice. Indeed, in short-short competitions, it’s not at all uncommon for a topic to be assigned outright. At the risk of repeating myself, read ALL OF THE RULES with care before you submit; such contests assume that entrants will be writing work designed exclusively for their eyes.

This should not, I feel, ever be the expectation for contests that accept excerpts from book-length works. Few entrants in these categories write new entirely new pieces for every contest they enter, with good reason: it would be quixotic. Presumably, one enters a book in a contest in order to advance the book’s publication prospects, not merely for the sake of entering a contest, after all.

Because the write-it-for-us expectation does sometimes linger, make sure to read the category’s definition before you decide to enter work you have already written. If the category is defined in such a way that writing like yours is operating at a disadvantage, your chances of winning fall sharply. The best way to careful with your entry dollar, and enter only those contests and categories where you have a chance of winning.

Mehitabel-pleasing strategy #9: make sure that you’re entering the right category — and that it’s the category you think it is.

Stop laughing. I would love to report that entries never come in labeled for the wrong category, but, alas, sometimes they do.

Why should you worry about something so easily corrected on the receiving end? Contests almost never allow judges to drop a misaligned entry into the correct category’s pile. Leaving Mehitabel to read the out-of-place entry, and to wonder: did the entrant just not read the category descriptions closely enough?

Often, this turns out to be precisely what happened.

This is not a time merely to skim the titles of the categories: get into the details of the description. Read it several times. Have a writer friend read it, then read your entry, to double-check that your work is in fact appropriate to the category as the rules have defined it.

This may seem like a waste of time, but truly, it isn’t. I have seen miscategorized work disqualified — or, more commonly, given enough demerits to knock it out of finalist consideration right away — but never, ever have I seen an entry returned, check uncashed, with an explanation that it was entered in the wrong category.

Next time, I shall discuss category selection a bit more. Yes, entering a literary contest is a complex task, but you’re a complex writer, aren’t you? You can do this.

Admit it: you’ve known that you could do it since you were 12 years old. And if you are 12 years old now, do you have any idea how jealous your elders are that blogs like this exist now? Why, back in my day…

Notice how close to 100 years old I sound already? Not an accident. Mind those cultural references, and keep up the good work!

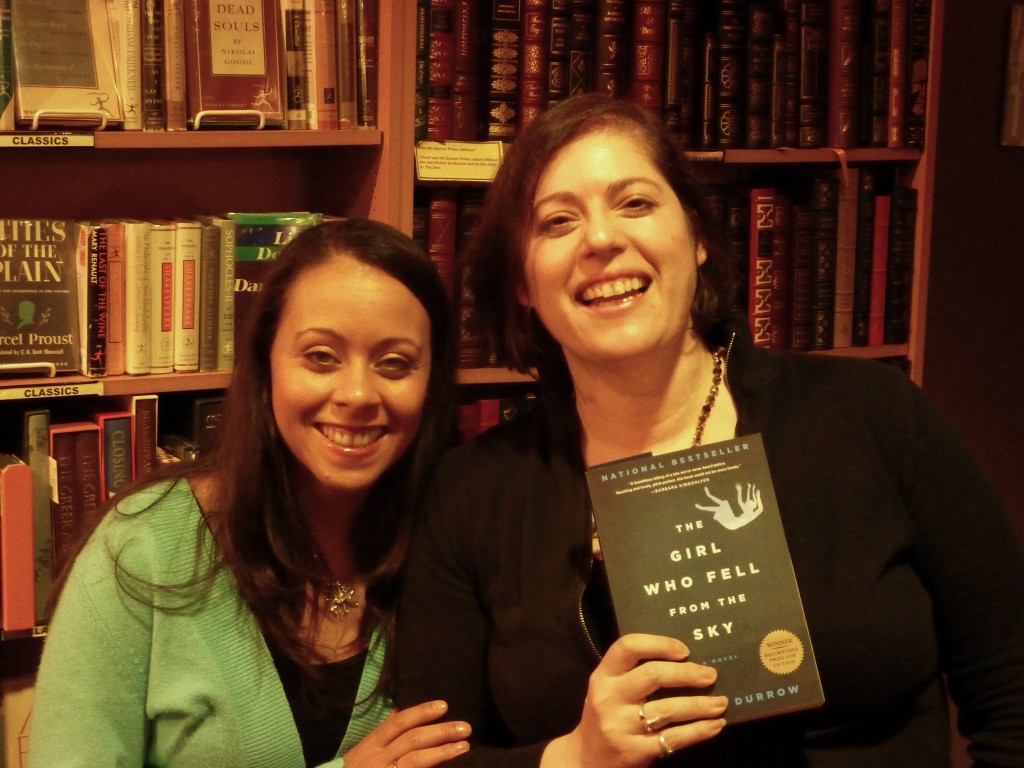

Rachel, the daughter of a Danish mother and a black G.I., becomes the sole survivor of a family tragedy after a fateful morning on their Chicago rooftop.

Rachel, the daughter of a Danish mother and a black G.I., becomes the sole survivor of a family tragedy after a fateful morning on their Chicago rooftop.