Did you hear that long, low howl of despair in the early working hours this morning, campers? Did its mournful resonance chill your bones, or at least lightly chill your marrow? Did it prompt you to yank the covers over your head, reasoning that whether that terrible noise came from the wind or the collective resultants of holiday merry-makers returning to work, you wanted no part of it?

If you’re a writer, I hope you obeyed that instinct, at least so far as acting upon that New Year’s resolution to pop that query or submission into the mail (or e-mail) goes. Why, you ask, teeth chattering at the far-off sounds of wailing and the rending of garments? Because today marks the statistically worst day of the year for writers to send off their work electronically — or for an agency or publishing house to receive it in either soft copy or hard.

And it’s the single worst day every year. That’s why the moans of agency screeners — those excellent souls known here at Author! Author! under the collective name of Millicent, to help us remember that these are human beings with individual literary tastes working for agents with personal preferences, as well as literary market savvy — invariably beard the heavens on not only the first work day of the year, but for most of January.

“Great Caesar’s ghost,” they cry, or some equivalent, “I’ve never seen so many queries/submissions/literary contest entries in my life!”

Actually, pretty much everyone who reads manuscripts for a living tends to indulge in a bit of moaning right about now, and with good reason: the single most common New Year’s resolution writers make involves sending off a query or finally submitting those requested pages. To toil anywhere in the publishing vineyard is to spend the opening days of every year buried under an avalanche of writers’ dearest hopes.

It’s heartwarming, really, how many writers actually follow through on their determination to make take those intimidating baby steps toward bringing their writing to professional attention. Even back when querying and submission meant typing and retyping one’s baby on an Underwood, hundreds of thousands of bright-eyed resolvers queried and submitted in early January, every year. Since the arrival of the personal computer made these tasks easier, and e-mail sped up communication, the volumes have risen astronomically. For e-mailing queriers and submitters in particular, the first weekend of the year seems just made for keeping those laudable promises to oneself.

“And why not?” aspiring writers proud of themselves for having worked up the not inconsiderable nerve required to hit the SEND key yesterday. “As you like to say here at Author! Author!, the only manuscript that stands absolutely no chance of getting published is the one that never gets sent out, right? So here I go! This is the year I’m going to land an agent/get published/place a short story/fulfill other writing dreams dependent upon the approval of other people!”

I applaud your enthusiasm, SEND-hitters, truly. It’s not an easy thing, offering up your beloved writing to an agent or editor’s judgment. You know the prospects your work is facing: it’s tough for an original story or new voice to break into the current extremely tight literary market. Add to that the tens of thousands of queries a well-established agencies will receive, and those are some pretty long odds for even a great story and wonderful style to surmount.

But you’ll never know unless you try, right? Good for you for putting your talent to the test — many a brilliant writer never finds the courage to let those pages be seen by another human being, much less a professional reader with the power and authority to bring that writing to a broader audience. An audience that might pay to read it, even.

May I make a gentle suggestion about tilting those odds ever so slightly in your favor, however? Would you consider not querying or submitting at precisely the same time as every other New Year’s resolver? Would it really not be fulfilling your resolution if you held off until, say, after Martin Luther King, Jr., Day, when the sheer volume hitting Millicent’s inbox will be significantly lower?

Would you, in short, wait until we’re past the month of the year in which rejection rates are predictably the highest?

I know, I know: you are positively aching to get that query or submission out the door. You’re resolved, in fact, that this will be the January that you crack the publication code. And the sooner you launch your plans, the better, right, because otherwise, you might lose momentum?

Admirable intentions, all, but I would urge you to rethink the last. As the media so eager to urge you to make that resolution — or, indeed, any New Year’s resolution — will be telling you in a few weeks, the average New Year’s resolution lasts only a few weeks. So woe unto he who hesitates, the prevailing wisdom goes, because as everybody knows, it’s absolutely impossible to begin any new project except immediately after the start of the year. If you miss the resolution boat by so much as a week — or, scare bleu! a month — all of the good New Year’s juju will have been sucked up by others. The laggard’s only recourse will be to sit, sad and glum, until the starting-gun goes off next year.

Unless one’s resolution was to lose weight, in which case the cultural reset button will be slapped sometime in the spring. “You wouldn’t want to miss your chance to get ready for swimsuit season?” the ambient culture will ask breathlessly. And off a significant proportion of the population will run again.

We each know in our heart of hearts, though, that just as surely as beauty is only skin deep, it’s completely untrue that there are only a couple of times per year in which it’s humanly possible to shed a few pounds. Or give up smoking. Or get that query out the door.

News flash: in publishing circles, there’s no special prize for a writer’s query being the first of the year, or even first 100,00th. Ditto with submissions: when a lot come at a time, they just pile up on agency desks. In either case, poor Millicent the agency screener is going to be working some awfully long hours until those volumes decrease a little.

Which means, in practice, that far from being the best time of the year to act upon those laudable plans, the first few weeks of the year are strategically the worst. Every year, literally millions of aspiring writers across this fine land of ours make precisely the same New Year’s resolution — with the entirely predictable result that every year, rejection rates skyrocket in the first few weeks of January. It thus follows as night the day that this is the time of year when a query or submission is most likely to be rejected.

Yes, you read that correctly. Your agile creative mind probably also leapt to the next correct conclusion: the same query or manuscript rejected in January might not have been had it dropped onto Millicent’s desk at another time of year. At minimum, the average query or submission will receive less reading time now than in, say, March.

That resounding thunk you just heard reverberating throughout the cosmos was the sound of thousands of first-time queriers and submitters’ jaws hitting their respective floors. For most writers new to the game, the notion that any factors other than the quality of the writing and excellence of the book’s concept could possibly play a role in whether a query or submission gets rejected is, well, new. If a manuscript is genuinely good, these eager souls reason, it shouldn’t matter when it arrives at an agency or small publishing house, right? No matter what else is on Millicent’s desk — or whatever else is going on at the agency, be it wedding, funeral, or just having read a proposal for the single worst nonfiction book since Mein Kampf — the only conceivable response to the advent of a good story well written must be the general dropping of all other work, cries of “Hallelujah!” and capering in the hallways, mustn’t it?

Um, no. I hate to be the one to break it to first-time submitters, but yours is not the only good manuscript that’s been written in English this year. And no true lover of literature should want it to be.

Yet almost without exception, writers responding to requests for manuscript pages act as though the agent or editor asking for it had been standing there, twiddling her thumbs, with nothing else to do until those pages arrived. Startlingly often, aspiring writers just presume that a request for pages, particularly in response to a conference pitch, constitutes a pro’s commitment to cease all work activity the moment those pages show up. Never mind that over half of requested materials never do show up — possibly because the writers in question queried or pitched before the book was done, or are trying to work up nerve to submit, or are waiting for the next new year to roll around — the horror is always the same.

“What do you mean,” indignant submitters everywhere huff, “it’s unrealistic to expect to hear back within a week or two — or a month or two? You don’t understand: the agent asked to read my manuscript!”

Yes, I know. He also asked to see other manuscripts. But apply the same logic earlier in the process, and springs a heck of a lot of holes: if a query for a truly well-written book — which is, contrary to popular opinion, not the same thing as a truly well-written query — lands on a pro’s desk, it will be received in precisely the same manner if it’s the only query arriving that day, or if it must howl for attention next to hundreds or thousands of incoming queries.

The latter is far, far more likely. Inevitable, in fact, if that query arrives anywhere near January first.

And that’s why, boys and girls, agents, editors at small publishing houses, and the screeners who read their day’s allotment of queries opened their e-mail inboxes this morning and groaned, “Why does every aspiring writer in North America hit SEND on January 1? Do they all get together and form a pact?”

Effectively, you do. You all formed such similar New Year’s resolutions.

So did the tens of thousands of successful pitchers and queriers from last year who decided that in the immediate wake of December 31, they were going to stop fiddling with their manuscripts and send those pages the agent of their respective dreams requested, unfortunately. It won’t have occurred to them, understandably, that each of them is not the only one to regard the advent of a new year as the best possible time to take steps to achieve their dreams.

Instead of — opening my calendar at random here — February 12th. Or the fifth of May. Or October 3rd. Or, really, any time of the year other than the first three weeks of January, when the sheer weight of tradition would guarantee that competition would be stiffest for the very few new writer slots available at any well-established agency or small publishing house.

That made half of you do a double-take, didn’t it? “Wait — what do you mean, very few new writer slots ?” queriers and submitters new to the game gasp. “Don’t agents take on every beautifully-written new manuscript and intriguing book proposal that comes their way?”

That’s a lovely notion, of course, but once again, pouring some water into that sieve will show us some holes. Think about it: reputable agents only make money when they sell their clients’ books to publishers and when those books earn royalties, right? There’s more to that than simply slapping covers on a book and shipping it to a local bookstore, after all. In any given year, only about 4% of traditionally-published books are by first-time authors, and those books tend as a group to be less profitable: unless a first-timer already enjoys wide name recognition, it’s simply more difficult for even the best marketing campaign to reach potential readers.

So at most agencies, most of the income comes from already-established clients — which means, on a day-to-day basis, a heck of a lot of agency time devoted to reading and promoting work by those authors. In recent years, selling even well-known authors’ work has gotten appreciably harder, as well as more time-consuming, yet like so many businesses, publishing houses and agencies alike have been downsizing. At the same time, since writing a book is so many people’s Plan B, hard economic times virtually always translate into increased query and submission volume.

Translation: agencies have to devote more hours than ever before to processing queries and submissions — an activity that, by definition, does not pay them anything in the short run — with fewer trained eyes to do it.

Why should any of that matter to a new writer chomping at the bit to land an agent in the new year? Several reasons. High querying and submission volume plus tight agency budgets result, inevitably, in less time spent on any given query or submission. The quicker the perusal, typically, the harder it is to impress an agent or an editor — and thus the more likely a time-strapped agency will be to employ Millicents to give queries and submissions the once-over. It’s not at all uncommon for a submission to have to make it past a couple of Millies empowered to say no before landing on the desk of anyone empowered to say yes.

So tell me: would you rather that Millicent had 15 other manuscripts to screen between now and lunch, if yours is No. 12, or 50? Or 150?

Got that appalling image firmly in your mind? Good. Now picture that same overworked, underpaid (or possibly not paid at all; many Millicents are interns) screener opening her e-mail inbox on the first Monday of the new year. Or the second. How much time do you think she’s going to be able to devote to each of the several thousand queries she’ll find deposited there? What about the next thousand arriving in her inbox tomorrow?

Actually, while you’re mentally trying on Millie’s moccasins, try taking a few more steps in them: how dismayed would you be at the prospect of doing ten (or more) times your usual work that day? Wouldn’t you tend to read just a trifle faster, with your fingertips lightly caressing the DELETE key? No matter how much you love literature and the good people who write it — as the overwhelming majority of folks currently working in publishing do — wouldn’t it be understandable if you found yourself screening those thousands of queries looking for quick reasons to reject, rather than eagerly perusing each one for every last clue that there might be talent hidden there?

Did I hear some momentary hesitation prior to your shouting, “By all the Muses’ togas, no! Were I lucky enough to read thousands upon thousands of queries every January, I would treat each and every one with respect — nay, reverence — down to the last semicolon and almost-legible signature!” Or at least before packing up the implied moral dilemma in your old kit bag and murmuring, “Well, if I ran the publishing world, querying wouldn’t be required; writers could simply send their manuscripts. Which agents would read in their entirety…”?

Ah, you just did the mental math, didn’t you? There’s a reason the vast majority of submissions get rejected on page 1.

But let’s get back to Millicent’s agonizing decision about how long to spend reading each query. Yes, it’s her job to find the diamonds amongst the rhinestones; yes, it’s unfair and even rather unreasonable that a writer of gem-like books must also devote time and energy to composing a brilliant query and synopsis. It’s an inescapable fact of our times, however — and you might want to sit down for this one — that the more successful an agent is, the more queries s/he will receive, and thus the greater the pressure on that agent’s screener to narrow down the field of contenders as rapidly as possible.

Why, you gasp, clutching your palpitating heart? Because time does not, alas, expand if one happens to have good intentions. Most good agents simply don’t have time to take on more than a handful of new clients per year.

Starting to think differently about the tens of thousands of queries that might be jostling yours in an agency’s inbox today if you hit SEND yesterday? Or the manuscripts that will be stacked next to yours if you stuff those requested pages into a mailbox later in the week?

Or, ‘fess up, were you one of the significant minority of aspiring writers whose first reaction to the idea that the agent of your dreams might be signing only 4 or 5 clients this year ran along the lines of “Apollo’s flame! I’d better make mine the first query he sees this year, then,” followed by a rapid glance at the nearest calendar? If so, relax: it’s not as though most agencies run on quotas, or as though your garden-variety great agent will fill his satchel with fabulous manuscripts for a month or two, then ignore everything else he reads until January 1 rolls around again.

It’s not, in short, as though the publishing world runs on New Year’s resolutions. (Although that’s an interesting idea.)

If you must take steps toward representation within the next few days or weeks, may I suggest something else that might improve your query’s chances? Invest the time in narrowing your querying list to agents with a solid, recent track record of selling books like yours.

Why will that help at the querying stage? Well, performing that research is relatively rare; a staggering number of queries arrive on the desks of people who have never represented a similar book in their professional lives. That’s a positive gift to a time-strapped Millicent, you know: the overwhelming majority of those thousands of New Year’s resolution-generated queries will be quite tempting to reject at first glance, and often for reasons that have little to do with the writing.

I find it sad that at this time of year especially, new writers often pick agents to query essentially at random. Their logic tends to run thus: if agents represent good books, and a book is well written, any agent could represent it successfully, right?

Actually, no: agents specialize, and it’s very much to both a good book and a good writer’s advantage that they should. The publishing industry is wide-ranging and complex, after all; no one who sells books for a living seriously believes that every well-written book will appeal to every single reader. Readers tend to specialize, too.

That’s why, in case you had been wondering, the publishing world thinks of books in categories. While an individual reader may well enjoy books across a variety of categories — indeed, most do — readers who gravitate toward a certain type of book share expectations. A devotee of paranormals, for instance, would be disappointed if she picked up a book presented as a vampire fantasy, but the storyline didn’t contain a single bloodsucker. By the same token, a lover of literary fiction would be dismayed to discover the novel he’d been led to believe was an intensive character study of an American family turned out to be an explosion-packed thriller.

As annoying as it may be for aspiring writers to think about limiting their readerships, literary fiction, fantasy, YA, Western, memoir, etc., are the conceptual containers used to ensure that a particular kind of writing will be marketed to the specific target audience already buying similar books. It’s not (as writers new to the game often assume) that you’re being asked to say who wouldn’t be interested in reading your story, or that (as writers considering for the first time the question of genre frequently fear) that agents don’t understand that creativity can confound readers’ expectations. The goal of labeling your manuscript with a book category — as you should do in your query — is to help match the right book with the right readers in the long run, as well as with the right agent in the short run.

Not only does approaching an agent experienced in working with books in your chosen category maximize the probability that she will enjoy the story you’re telling — it also maximizes the probability that she’ll already have the professional connections to sell it. Since no editor or publishing house brings out every different kind of book, agents would be less effective at their jobs if their only criterion for selecting which books to represent was whether they liked the writing. Editors and imprints, too, tend to specialize, handling only certain book categories.

As a direct and sometimes disturbingly swift result, there is no query easier for Millicent to reject than one for a book in a category her boss does not represent. No matter how beautifully that query presents the book’s premise, that story will be a poor fit for her agency. Approaching an agent simply because he’s an agent, then, tends to be the first step on a path to rejection.

Especially, if you can stand my harping on this point, if a writer is doing it in January. New Year’s resolvers are frequently in a hurry to see results. You would not believe how many aspiring writers will simply type literary agent into Google, e-mailing the first few that pop up. Or how many more will enter a generic term like fiction into an agency search, intending to query the first 80 on the list, usually without checking out any of those agents’ websites or listings in one of the standard agents’ guides to find out what those fine folks actually represent.

That’s a pity, because — feel free to sing along; you should know the tune by now — not only is an agent who already has a solid track record selling a particular category more likely to be interested in similar books, but that agent will also have the connections to sell that type of book. Which means, ultimately, that approaching an agent specializing in books like yours could mean getting published faster than just querying every agent in Christendom.

Yes, really. You don’t just want to land any agent, do you? You want to entrust your book to the best possible representative for it.

I sense some grumbling out there. “But Anne,” the disgruntled mutter, and who could blame you? “All I want to do is get my book published; I know that I need an agent to do that. But I don’t have a lot of time to devote to finding one. Thus my wanting to act upon my New Year’s resolution toute suite: I had a few spare moments over the holidays, so I was finally able to crank out a query draft. I understand that it might be a better use of my querying time to rule out agents who don’t represent my type of book at all, but why wouldn’t sending my query to a hundred agents that do be the fastest way to reach the right one? That way, I could get all of my queries out the door before I lose my nerve — or my burst of new year-fueled energy.”

That’s a good question, one that richly deserves an answer. I’ve written quite a bit on this blog about why generic queries tend not to be received as kindly in agencies as those that are more tightly targeted; there’s a reason, after all, that the stock advice on how to figure out which agents to query has for years been find a recently-released book you like and find out who represented it. Admittedly, that excellent axiom was substantially easier to follow back in the days when publishers routinely allowed authors to include acknowledgements; it used to be quite common to thank one’s agent. Any agency’s website will list its primary clients, however, and I think you’ll be charmed to discover how many authors’ websites include representation information.

In case I’m being too subtle here: no recipient of a generic query will believe that its sender had no way to find out what kinds of books she represents, or which established authors. Neither will her Millicent. Sorry about that.

Small wonder, then, that any screener that’s been at it a while can spot a query equally applicable to every agency in the biz at twenty paces — especially if, as so often is the case with mass-produced mailed queries, it’s addressed to Dear Agent, rather than a specific person. Or if it is rife with typos, too informal in tone, or simply doesn’t contain the information any agent would want to know before requesting pages. Like, say, the title or the book category.

Oh, you think I’m kidding about the title? Millicent’s seen 10 queries missing it today.

Given the intensity of competition for Millicent’s attention on an ordinary day of screening, any one of the problems mentioned above could trigger rejection. During the post-New Year’s query avalanche, it’s even more likely.

Let’s take a moment to picture why. Agents and editors, like pretty much everybody else, often enjoy the holidays; they’ve even been known to take time off then, contrary to popular opinion amongst New Year’s resolution queriers. Since it’s hard to pull together an editorial committee — and thus for an acquiring editor to gain permission to pick up a new book — with so many people on vacation, agents and editors alike frequently use work time during the holidays to catch up on their backlog of reading. (See earlier point about existing clients’ work.) It’s not, however, particularly common to employ that time reading queries.

Why? The annual New Year’s resolution barrage about to descend, of course: they know they’ll be spending January digging out from under it. How could they not, when all throughout the holiday season, writers across the English-speaking world have been working up both drafts and nerve?

Not only do the usual post-vacation backlog await them, but so will the fruits of every New Year’s resolver’s enthusiasm. Every inbox will be stuffed to overflowing; thousands of e-mails will be crowding the agency’s computers; the mailman will be staggering under armfuls of envelopes and manuscript boxes.

Care to revise your answer about how quickly you would be inclined to read through that tall, tall stack of queries if you were Millicent? How much time would you tend to spend on each one, compared to, say, what you might devote to it on March 8th? Would you be reading with a more or less charitable eye for the odd typo or a storyline that did not seem to correspond entirely with your boss’ current interests?

Before you respond to those burning questions, consider: working her way through that day’s correspondence is necessary to clear Millicent’s schedule, or even enable her to see her desk again. As January progresses, each day will bring still more for her to read. Not every New Year’s resolution gets implemented at the same pace, after all, nor do they have the same content. This month, however, Millicent may be sure that each fresh morning will provide additional evidence that writers everywhere have their noses to the wheel — and each Monday morning will demonstrate abundantly that New Year’s resolvers are using their weekends well.

At least for the first three weeks or so. After that, the resolution-generated flood peters out.

Not entirely coincidentally, that’s also when New Year’s resolution queriers tend to receive their first sets of mailed rejections — and when e-mailing queriers begin to suspect that they might not hear back at all. (For those who just clutched your hearts: rejection via silence has been the norm for the past few years.) The timing on those rejections is key to Millicent’s workload over the next few months, as an astonishingly high percentage of first-time queriers give up after only one or two attempts.

That’s completely understandable, of course: rejection hurts. But as any agent worth her salt could tell you, pushing a book past multiple rejections is a normal and expected part of the publication process. Every single author you admire has had to deal with it at some point in the process. Yes, really: just as — again, contrary to popular opinion — even the best books generally get rejected by quite a few agents before the right one makes an offer to represent it, manuscripts and book proposals seldom sell to the first editor that reads them.

That should give you hope, by the way: while it may feel like a single rejection from a single agent represents the publishing industry’s collective opinion about your writing, but it’s just not true. Individual agents have individual tastes; so do their Millicents. Keep trying until you find the right fit.

But you might want to wait a few weeks — and if it’s not clear yet why, I ask you again to step out of a writer’s shoes and into Millicent’s. If you knew from past experience how many fewer queries would be landing on your desk a few weeks hence, would you read through this week’s bumper crop more or less rapidly than usual? Would you be more or less likely to reject any particular one? Or, frankly, wouldn’t you be a bit more tired when you read Query #872 of the day than Query #96?

Still surprised that rejection rates are higher this time of year? Okay, let me add another factor to the mix: in the United States, agencies must produce the tax information for their clients’ advances and royalties for the previous year by the end of January.

That immense sucking sound you just heard was all of the English majors in the country gasping in unison. Representing good writing well isn’t just about aesthetic judgments, people; it’s a business. A business based upon aesthetic judgments, of course, but still, it’s not all hobnobbing with the literati and sipping bad Chardonnay at book launches.

It’s also a business run by people — living, breathing, caring individuals who, yes, love good writing, but also can get discouraged at the sight of a heavier-than-usual workload. They can become tired, like anyone else. Or even slightly irritated after reading the 11th generic query of the day, or spotting five misspellings in the 111th.

Imagine, then, what it might feel like to read the 1,100th. Of the day, if one happens to be screening within the first few weeks of January.

To repeat my word du jour: wait. You’re an original writer; why would you need to pick the same day — or month — to launch your dreams as everybody else?

Oh, and if you choose to disregard this advice — and I’ve been at this long enough to have accepted that a hefty percentage of you will — please, remember to include not only your manuscript title and book category in your query, but also to tuck your contact information into the letter. If you’re submitting a manuscript, include a title page with your contact information. You want the agent that’s just fallen in love with your voice to be able to tell you so, don’t you?

Stop laughing, please. You would be flabbergasted at how often e-mailing queriers and submitters just assume that all Millicent or her boss would have to do to get in touch would be to hit REPLY. I guess they’ve never heard of a forwarded e-mail.

Best of luck with your New Year’s resolutions — and with implementing them in the way that’s most likely to bring your dreams to fulfillment. Keep up the good work!

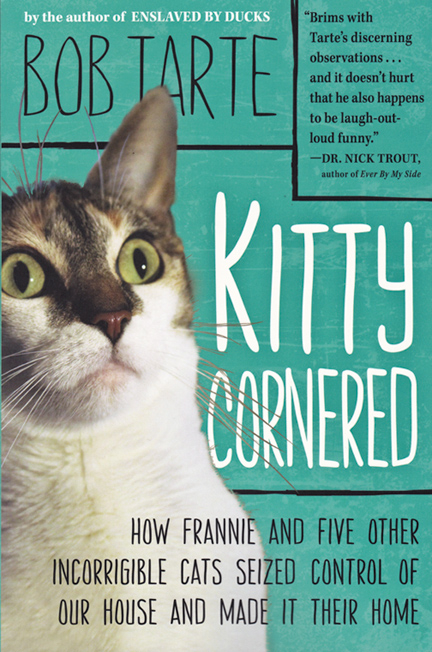

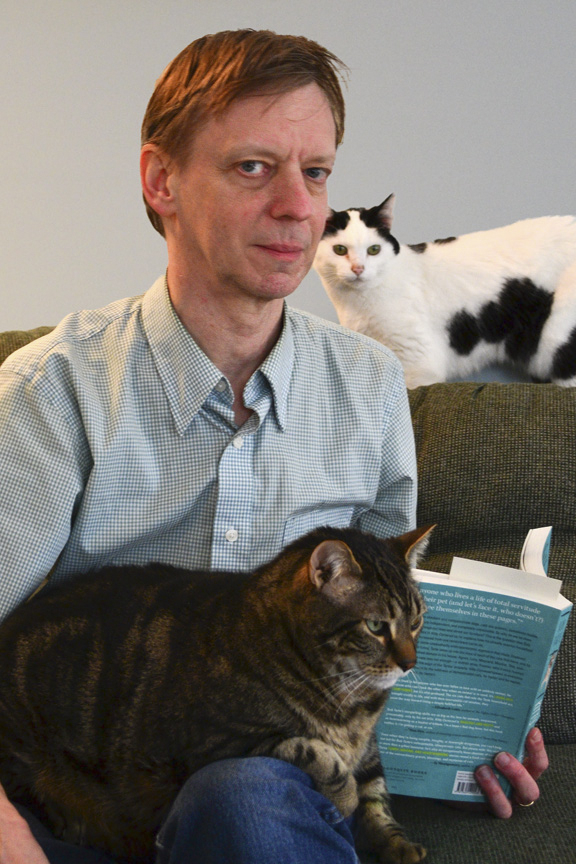

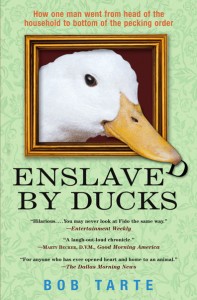

When Bob Tarte left the city of Grand Rapids, Michigan for the country, he was thinking peace and quiet. He’d write his music reviews in the solitude of his rural home on the outskirts of everything.

When Bob Tarte left the city of Grand Rapids, Michigan for the country, he was thinking peace and quiet. He’d write his music reviews in the solitude of his rural home on the outskirts of everything. Bob Tarte’s second book, Fowl Weather, returns us to the Michigan house where pandemonium is the governing principle, and where 39 animals rule the roost. But as things seem to spiral out of control, as his parents age and his mother’s grasp on reality loosens as she battles Alzheimer’s disease, Bob unexpectedly finds support from the gaggle of animals around him. They provide, in their irrational fashion, models for how to live.

Bob Tarte’s second book, Fowl Weather, returns us to the Michigan house where pandemonium is the governing principle, and where 39 animals rule the roost. But as things seem to spiral out of control, as his parents age and his mother’s grasp on reality loosens as she battles Alzheimer’s disease, Bob unexpectedly finds support from the gaggle of animals around him. They provide, in their irrational fashion, models for how to live.