It never rains good news but it pours here at Author! Author! Long-time reader Janiece Hopper‘s first novel, Cracked Bat, is being released today by Ten Pentacles Press. Congratulations, Janiece!

You know how every time I talk about book categories, I lecture you all long and hard about how the industry expects you to pick one of the already-established one and be done with it? Well, Janiece’s book honestly does cut across several. Since we’re approaching conference season again, let’s take a gander at the novel’s pitch:

Linnea Perrault is the editor of The Edge, a successful community newspaper. Happily married to Dan, Spinning Wheel Bay’s premier coffee roaster and owner of The Mill, she is the mother of an adorable four-year-old daughter who insists upon lugging a fifteen-pound garden dwarf everywhere they go. When Linnea’s wealthy father returns to their hometown to make amends for abandoning her to a cruel stepfather twenty-eight years earlier, she painfully resurrects his old place in her heart. He buys the local baseball team. Before long, fairy tales, Islamic mystics, and a host of cross-cultural avatars come into play as the team is propelled to the top of the league. After a foul pass and an accident at the stadium, Linnea finds herself locked in the stone tower of pain as she realizes how much the man she married is like the father she never knew. Doctors can’t diagnose her debilitating condition, but kind, magical strangers give her a chance to save her soul. Cracked Bat is dedicated to the approximately five million people who have experienced the mystifying and frustrating ailments of myofascial pain syndrome, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue.

Did you catch the extremely clever marketing twist here? The author not only identified the target market for the book, but (like a reasonable person and prudent writer aware of how the business works), she did not leave estimating just how big that potential market was to an agent or editor’s imagination.

Trust me, left to their own devices, they virtually always guess low.

Since Janiece has been kind enough to let me run amok with her marketing materials, let’s take a peek at her author photo:

Nice, isn’t it? I’m guessing that wasn’t entirely accidental — or that this represents Janiece’s first sitting for her author photo.

All too often, aspiring writers leave the genuinely difficult task of coming up with an author photo they like until a week before they need to provide their publishers with one. Unless one happens to be a supermodel with a portfolio crammed with fabulous shots, this is a strategic mistake.

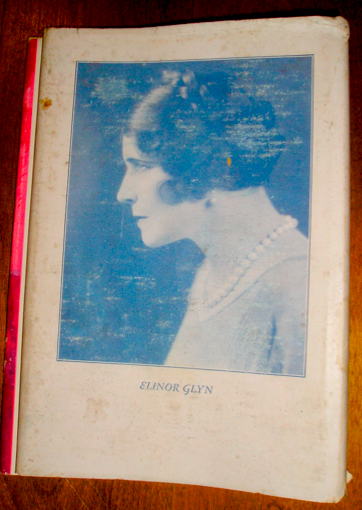

Why? Well, gone are the days when your garden-variety publisher paid some ritzy photographer to spend several hours coming up with something like this for a book jacket:

That’s the jacket photo for the first edition of Elinor Glyn‘s 1927 bestseller, IT, incidentally — and yes, Madame Glyn was in fact the person who coined the phrase “The It Girl.”

Clearly, this is a photo designed to maximize intensity — which, then as now, would have been a marketing decision. And with good reason: when IT was published, Madame Glyn had been THE name in potboiler romance for a decade. Her breakthrough novel, Three Weeks, was considered so scandalous when it came out that it inspired a popular song:

Would you like to sin

With Elinor Glyn

On a tiger skin?

Or would you prefer

To err with her

On some other fur?

Catchy, no? Even before World War I, most authors would have happily cut off a toe or two in exchange for that kind of free publicity.

These days, authors are almost universally expected to provide their publishers with jacket and promotional photos, rather than the other way around, so accepted a practice that I just go ahead and include mine on my author bio when I submit a manuscript.

But that’s not why you should start thinking about blandishing a photographer friend into snapping you now. Unless you are the aforementioned supermodel, chances are that it will take many, many shots to come up with one that you like enough to want it emblazoned upon your book forever and ever.

When would you rather be trying to capture that immortal look, before an agent picks up your book or in the 24-hour period between when your publisher first mentions needing your photo and when the marketing department expects to receive it?

Believe me, you’ll have other things to do at that point. Like providing the marketing department with the names, addresses, and telephone numbers of every bookstore in every city where you know even a single soul.

You think I’m kidding about that, don’t you?

Everyone, please join me in a round of applause for Janiece — and a thank-you for reminding me to bring up the author photo issue.

Since I’ve covered so many issues today already, I’m a trifle reluctant to launch into the promised practical examples of the Short Road Home, lest this post turn into a 15-page treatise. But since the editors and critics of 1927 were much less concerned with moving a plot along than their current equivalents, let me take a quick stroll through IT to see if one jumps out at me.

While I’m leafing, I should probably underscore that novels (or memoirs) published more than 20 years ago would not be the best role model choices for pacing a book a writer planned to submit today. Yes, even if the book in question is a recognized classic.

It’s tempting, isn’t it, to blame agents for this, since over that particular period they have become the weeders-out of what editors at the major US publishing houses see? (In case you didn’t know, all of the big American publishers now have policies specifically forbidding considering unagented work. If an editor from one of them implies otherwise on a conference podium — not unheard-of — ask point-blank if he’s allowed to pick up a book by an unagented author before pitching. Most of the time, even if they love a book they find at a conference, they will merely refer its writer to an agency, anyway, so you’re usually better off using your pitch appointments with editors from smaller presses who do not have this policy.)

But the fact that pacing standards have sped to near-breakneck rates in recent years really isn’t the agents’ fault: it’s genuinely difficult for them to sell more moderately-paced books. Ditto with long ones.

Why? The price of paper has risen astronomically in recent years, as has the cost of binding. This, in case you are curious, is the primary reason that Millicent the screener tends to have a knee-jerk negative reaction to a first novel much over 100,000 words (estimated, which translates to 400 pages in standard format; if what I just said sounded like Urdu to you, please see the WORD COUNT category at right): at 120,000, the cost of binding shoots up.

Bad news for all of us who grew up wanting to emulate John Irving’s pacing, certainly. Or really, any meganovelist who wrote prior to the Second World War.

For reasons of history, then, as well as practicality, Millicent starts to tense up when a submission’s pace begins to slow. But that doesn’t mean that it’s in a writer’s interest to skim over interesting conflict too quickly with a Short Road Home.

Oh, goodie, I’ve just found a lulu of an example. IT’s impoverished society-girl heroine, Ava Cleveland, is desperate for money to maintain her lifestyle in the face of her brother’s bordering-on-criminal gambling debts. When our scene begins, she’s just told her friends that she is spending a season in the country to hide the fact that she is — gasp! — going to be asking her admirer John Gaunt for a job:

So she shut up the Park Avenue flat and dodged her creditors and disappeared to “Virginia” — which happened on the map to be her old nurse’s abode in an ancient house in the old-fashioned poorer quarter of Brooklyn. Close, if she had known it, to one of John Gaunt’s hospitals for children.

Something made her restless, even from the first day of her arrival — so at last she looked at John Gaunt’s card again — and rang Hanover 09410 — once more.

I’m going to pause here to ask you a trenchant question: you’re already a trifle bored, aren’t you? That’s probably because you’re so used to the current standards of writing that even this much summary strikes you as skirting the edge of show-don’t-tell comfort.

But actually, Millicent probably wouldn’t have made it beyond the first sentence of this excerpt — and for a reason that is VERY common in present-day submissions. Any idea why?

Hint: go back and take a gander at that first sentence. Quite a few ands in it, aren’t there? And technically, quotation marks should not be used to indicate so-called; italics would have been the preferred choice here.

But let’s remember it’s 1927, when submission standards were a bit more lax. Moving on:

Miss Shrimper answered and was as insulting as she could be, when she heard a refined female voice…No, Mr. Gaunt could not come to the phone — he never came to the phone! The idea!

Ava’s voice sharpened. “Be good enough to tell him that the lady he met at Mrs. Meriton’s is speaking.”

It is doubtful that even this would have succeeded, had not John Gaunt himself chanced to come out from his inner shrine and seem Miss Shrimper’s acid face — something told him instantly that it was Ava trying to get through to him.

John Gaunt turned to re-enter his private room. “Put her through,” was all he said.

And as she did so, Miss Shrimper’s eyes filled with apprehensive tears.

Okay, Anne again here. Did you see what just happened?

The narrative had gotten a legitimate conflict going between Ava and Miss Shrimper (albeit through having chosen to summarize the latter’s indignation rather than showing it through dialogue and tone) — when along comes stupid old John (called by both names each time he appears, please note, a rookie narrative mistake) to intuit what’s going on by some mysterious, doubtless magical means.

Presto! Conflict killed.

Not content with abruptly cutting off the hostility between the two women, Glyn goes on to minimize Ava’s difficulties in asking for what she wants — another version of the Short Road Home. To top it off, her characters take refuge in that most boring of dialogue forms, the ultra-polite. Lookee:

“Good morning, Miss Cleveland.” His voice was deep, and Ava, at the other end, quivered strangely. “What can I do for you?”

“I want to — work.”

“You had better come and see me tomorrow at eleven, then — I am altering some posts in my office. You may wish to give the name of Miss Clover, perhaps?” The tones were cold as steel and entirely businesslike.

Ava experienced a chill — but “Miss Clover!” That was an idea! “Very well, she answered, and put down the phone.

John Gaunt lay back in his chair and smiled.

“How surprised she will be,” he said to himself. Then he went out and had his rather long hair trimmed slightly so that its thick, deep waves lay close against his Napoleonic head. His nails, which Ava had thought too brilliantly polished, were given a still brighter luster too. Then he went to his Club and was sphinx-like and almost surly with one or two business friends he met.

I could have stopped earlier, but who was I to deny you that Napoleonic head? (Hard to imagine that less than a century ago, that description would have been considered inherently attractive, isn’t it?)

I could run through a laundry list of all the reasons Millicent might give for not making it all the way through this excerpt — the repeated two-part name, the telling rather than showing (how exactly may one be sphinx-like without either posing riddles or having a cat’s head?), the paragraph containing only a single sentence — but that’s not what I want you to focus upon here.

Instead, concentrate on just how effectively the use of the Short Road Home in this last bit smothered ALL of the following:

(a) the tension that the narrative summaries seem to be assuring the reader exists;

(b) the sense that Ava was having to overcome any scruples in going to work, since she just blurted out the request with no preamble or hesitation, beyond the moment indicated by the dash;

(c) any indication that Ava was going to have to beg for the job, since John Gaunt agrees instantly, and

(d) any anticipation the reader might have felt prior to this scene about difficulties Ava might encounter at her first job, since John Gaunt (ugh) has very kindly handed her a simple alternative to having to be honest about who she is — and in case we were in any doubt about this suggestion’s utility, Ava considerately just tells the reader that it’s a good idea.

A pretty efficient page’s work — and that’s not even counting the significant achievement of impressing the reader with Ava’s apparent inability to hold still for more than a paragraph without quivering for reasons she doesn’t understand. (Nor do we.)

By handling potentially conflict-ridden material in this manner, Madame Glyn effectively killed the tension of what should have been a harrowing scene. So much so that I sincerely doubt that today’s Millicent would have kept reading all the way through it.

The funny thing is, this super-quick resolution is not even representative of the rest of the book. Oh, Madame Glyn does favor the Short Road Home from time to time — but given the exchange above, would you be expecting Ava to try to sell herself to John in order to save her brother? Or John to use the solicitation of same as a complex ruse to propose marriage?

The moral: just because a storyline is full of conflict doesn’t necessarily mean that the book will be a page-turner. How a writer chooses to present that conflict is crucial.

Frankly, Millicent would be a less cynical woman if more aspiring writers realized this.

More on the subject follows tomorrow, of course. Beware of unexplained quavering, everybody, and keep up the good work!