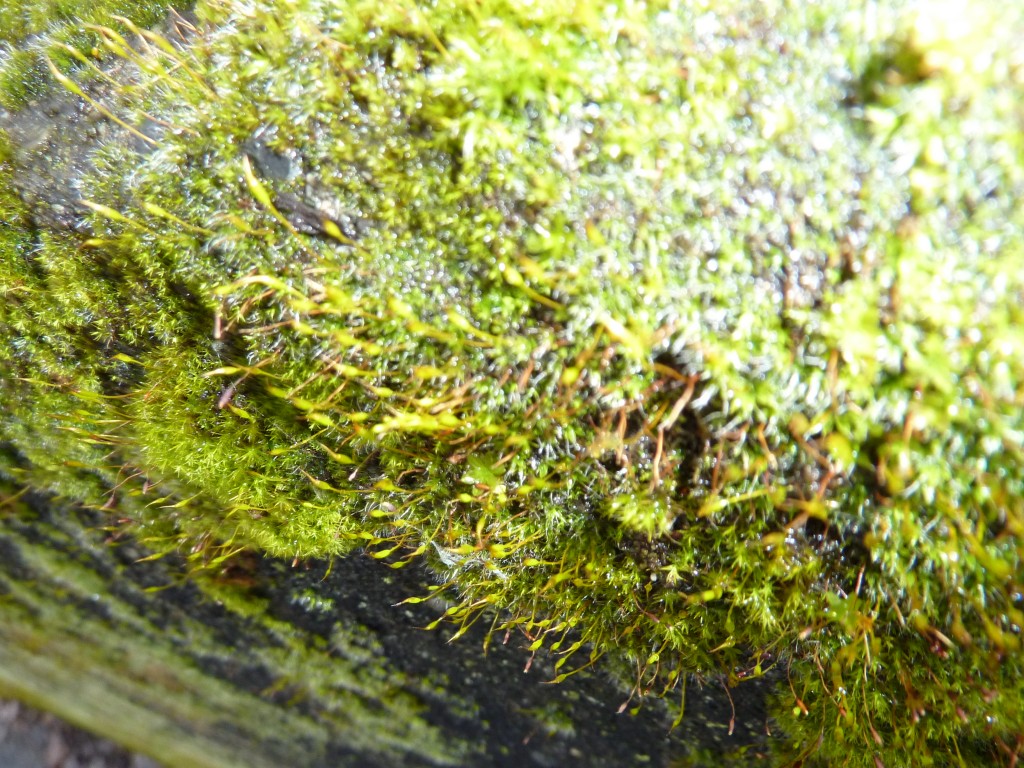

Okay, I’ll admit it: I’m a big fan of artists’ looking at ordinary, everyday things and showing us the beauty of them. Take the photograph above, for instance: that’s perfectly ordinary moss on a perfectly ordinary concrete wall, photographed during a perfectly ordinary Seattle rainstorm. (And while I was clicking away, crunching my body sideways in order to get this particular shot, a perfectly ordinary mother told her perfectly ordinary wee daughter to veer away from the crazy lady. Yet another case of a misunderstood artist — and another a child being warned that if she tries to look at something from an unusual perspective, people are bound to think she’s strange.)

Perhaps not astonishingly, writers tend to find beauty in found words. An overhead scrap of conversation, perhaps, or a favorite phrase in a book. And often — far too often, from Millicent the agency screener’s perspective — aspiring writers celebrate these words lifted from other places by quoting them at the beginning of their manuscripts.

That’s right, campers: today, I’m going to be talking about proper formatting for that extremely common opening-of-text decoration, the epigraph.

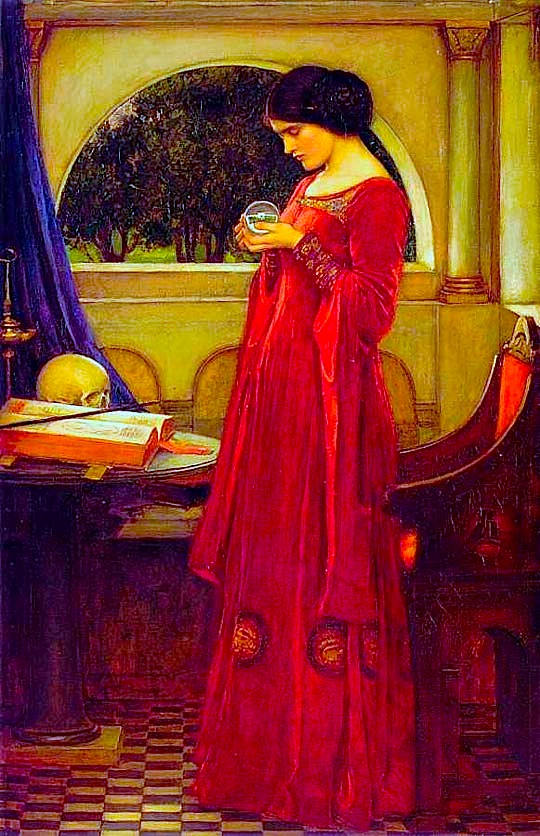

You know, those nifty little quotes from other sources that we writers so adore — and it’s not as though the publishing industry doesn’t encourage us to think of them this way: in a published book, the epigraph, if any, is almost always presented in a place of honor, either at the top of each chapter or by itself on the page before the text proper starts. Take, for example, the placement of the well-known epigraph to Alice Walker’s THE COLOR PURPLE, an excerpt from Stevie Wonder’s DO LIKE YOU:

Okay, so that picture didn’t really do the words justice; not all of my photos can be winners, you know. (In case you don’t happen to have a copy of the book handy, the epigraph runs thus: Show me how to do like you/Show me how to do it.) It does, however, show the prominent placement the epigraph affords: even in my cheap, well-worn paperback edition, it scores a page all to itself.

In other words, not only is it allocated space; it’s allocated white space, to set it off from the other text. In an age when acknowledgments pages are routinely omitted, along with the second spaces after periods and colons, in order to save paper, that is quite an honor. Especially since nobody but writers like epigraphs much — of that, more later.

But we writers think they’re great, don’t we? Especially if they’re from obscure sources; they feel so literary, don’t they? Or deep-in-the-national-psyche, know-your-Everyman populist, if they’re from songs. By evoking the echo of another writer’s words, be it an author’s or a songwriter’s, we use them to set the tone for the story to come.

I don’t think conceptual aptness is all there is to the appeal, though. There is something powerfully ritualistic about typing the words of a favorite author at the beginning of our manuscripts; it’s a way that we can not only show that we are literate, but that by writing a book, we are joining some pretty exalted company.

Feeling that way about the little dears, I truly hate to mention this, but here goes: it’s a waste of ink to include them in a submission. 99.9998% of the time, they will not be read at all.

Stop glaring at me; it’s not my fault. I don’t stand over Millicent with a bullhorn, admonishing her to treat every syllable of every submission with respect. (Although admittedly, it’s an interesting idea.)

The sad fact is, most Millicents are specifically trained not to read epigraphs in manuscripts; it’s widely considered a waste of time. I’ve literally never met a professional reader who doesn’t simply skip epigraphs in a first read — or (brace yourselves, italics-lovers) any other italicized paragraph or two at the very beginning of a manuscript, even if it was .

Oh, dear — I told you to brace yourselves. “Why on earth,” italics-lovers the world over gasp in aghast unison, “would any literature-loving human do such a thing? Published books open all the time with italicized bits!”

A fair question — but actually, there’s a pretty fair answer. Most Millicents just assume, often not entirely without justification, that if it’s in italics, it doesn’t really have much to do with the story at hand, which (they conclude, not always wrongly) begins with the first line of plain text.

Of course, there’s another reason that they tend to skip ‘em, a lot less fair: at the submission stage of the game, no one cares who a writer’s favorite authors are. A writer’s reading habits, while undoubtedly influential in developing his personal voice, are properly the subject of post-publication interviews, not manuscript pre-screening time. After all, it’s not as though Millicent can walk into her boss’ office and say, “Look, I think you should read this submission, rather than that one, because Writer A has really terrific literary taste,” can she?

Whichever reason most appeals to the Millicent who happens to have your submission lingering on her desk (just under that too-hot latte she’s always sipping, no doubt), she’s just not going to be reading your carefully-chosen epigraph. She feels good about this choice, too.

Why? Well, the official justification for this practice — yes, there is one to which Millicents will admit in public — is not only reasonable, but even noble-sounding: even the busiest person at an agency or publishing house picks up a submission in order to read its author’s writing, not somebody else’s.

Kinda hard to fault them for feeling that way, isn’t it, since we all want them to notice the individual brilliance of our respective work?

Sentiment aside, let’s look at what including an epigraph achieves on a practical level, as well as its strategic liabilities. Assume for a moment that you have selected the perfect quotation to open your story. Even better than that, it’s gleaned from an author that readers in your chosen book category already know and respect. By picking that quote, you’re announcing from page 1 — or before page 1, if you allocate it its own page in your manuscript — you’re telling Millicent that not only are you well-read in your book category, but you’re ready and able to take your place amongst its best authors.

Sounds plausible from a writerly perspective, doesn’t it? That’s one hard-working little quote.

But what happens when Millicent first claps eyes on your epigraph? Instead of startling her with your erudition in picking such a great quote, the epigraph will to prompt her to start skimming before she gets to the first line of your text — AND you will have made her wonder if you realized that manuscript format and book format are not the same.

So you tell me: was including it a good idea? Or the worst marketing notion since New Coke?

If that all that hasn’t convinced you, try this on for size: while individual readers are free to transcribe extracts to their hearts’ contents, the issue of reproducing words published elsewhere is significantly more problematic for a publishing house. While imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery, reproduction of published text without the author’s permission is known in the biz by another, less flattering name: copyright infringement.

What does that mean in practice? Well, if the epigraph is from a book that is not in the public domain, the publisher will need to obtain explicit permission to use any quote longer than fifty words. Ditto for any quote from a song that isn’t in the public domain, even if it is just a line or two.

So effectively, most epigraphs in manuscripts might as well be signposts shouting to an editor: “Here is extra work for you, buddy, if you buy this book! You’re welcome!”

I’m sensing some disgruntlement out there, amn’t I? “But Anne,” I hear some epigraph-huggers cry,

“the material I’m quoting at the opening of the book is absolutely vital! The book simply isn’t comprehensible without it!”

Before I respond, let me ask a follow-up question: do you mean that it is crucial to the reader’s understanding the story, or that you have your heart set on that particular quote’s opening this book when it’s published?

If it’s the latter, including the epigraph in your manuscript is absolutely the wrong way to go about making that dream come true. Like any other book formatting issue, whether to include an epigraph — or acknowledgements, or a dedication — is up to the editor, not the author. And besides, a submission manuscript should not look like a published book.

Consequently, the right time to place your desired epigraph under professional eyes is after the publisher has acquired the book, not before. You may well be able to argue successfully for including that magically appropriate quote, if you broach the subject at the right time.

And just to set my trouble-borrowing mind at ease: you do know better than to include either acknowledgements or a dedication in your manuscript submissions, right? It’s for precisely the same reason: whether they’ll end up in the published book is the editor’s call. (I wouldn’t advise getting your hopes up, though: in these paper-conserving days, the answer is usually no on both counts, at least for a first book.)

Quite a few of you were beaming virtuously throughout those last three paragraphs, though, weren’t you? “I know better than to second-guess an editor,” you stalwart souls announce proudly. “I honestly meant what I said: my opening quote is 100% essential to any reader, including Millicent and her cohorts, understanding my work.”

Okay, if you insist, I’ll run through the right and wrong ways to slip an epigraph into a manuscript — but bear in mind that I can’t promise that even the snazziest presentation will cajole Millicent into doing anything but skipping that quote you love so much. Agreed?

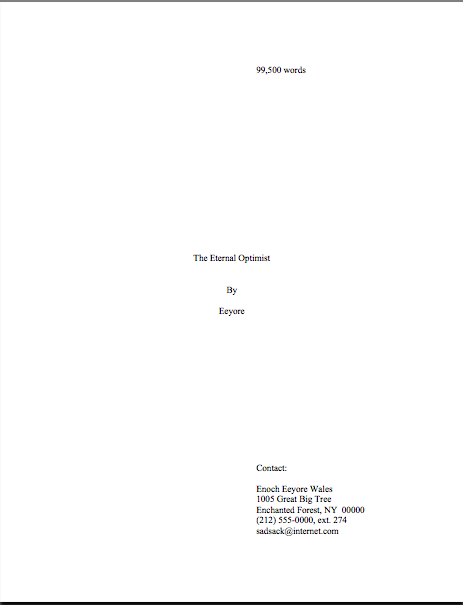

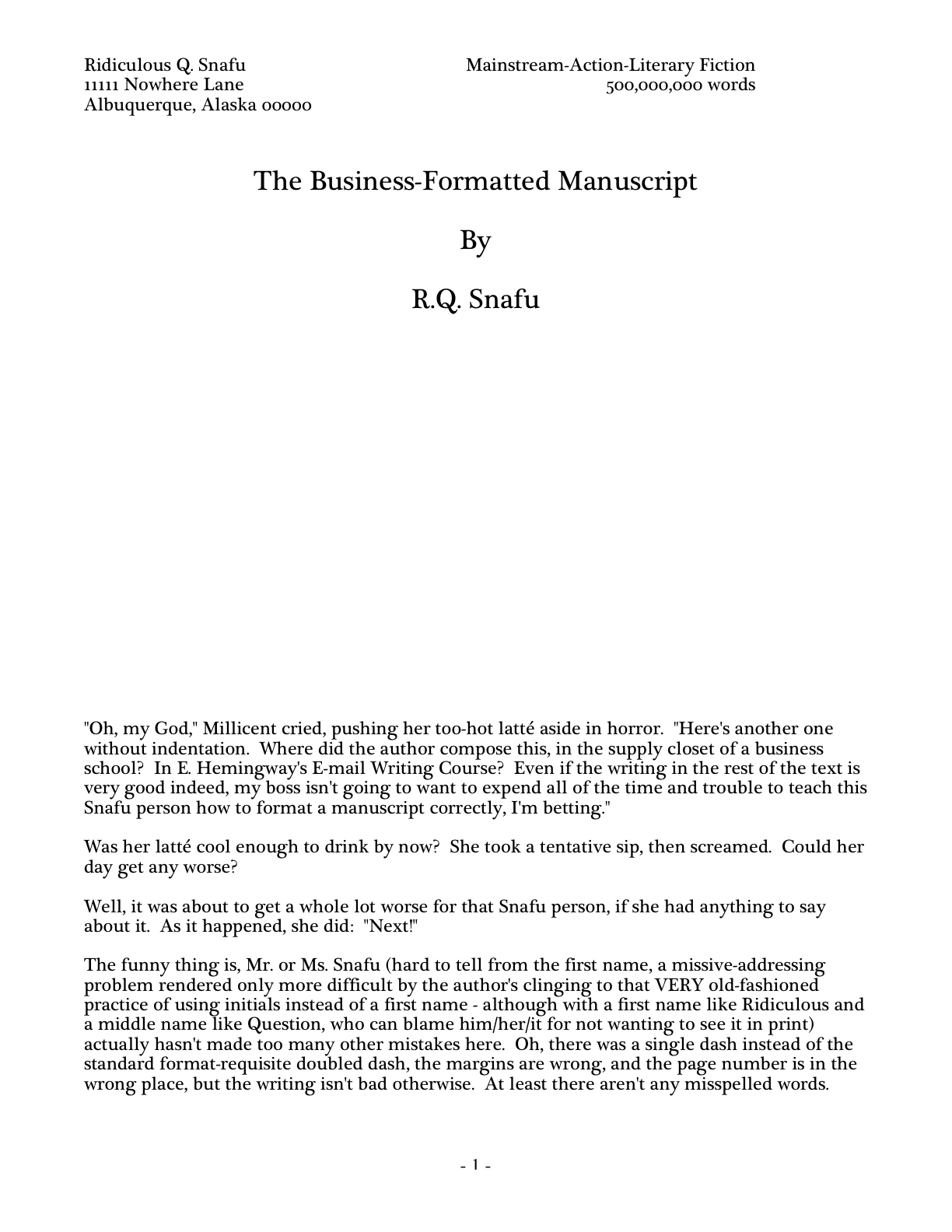

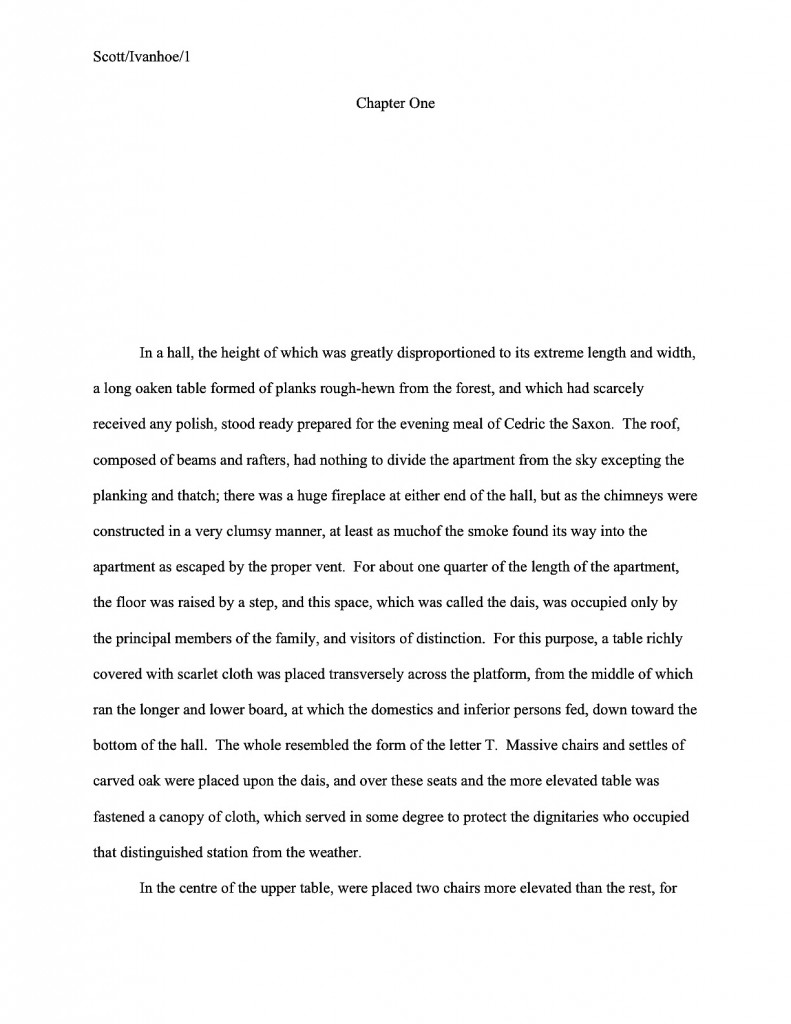

For starters, do not, under any circumstances, include a quote on the title page as an epigraph — which is what submitters are most likely to do, alas. Let’s take a gander at what their title pages tend to look like:

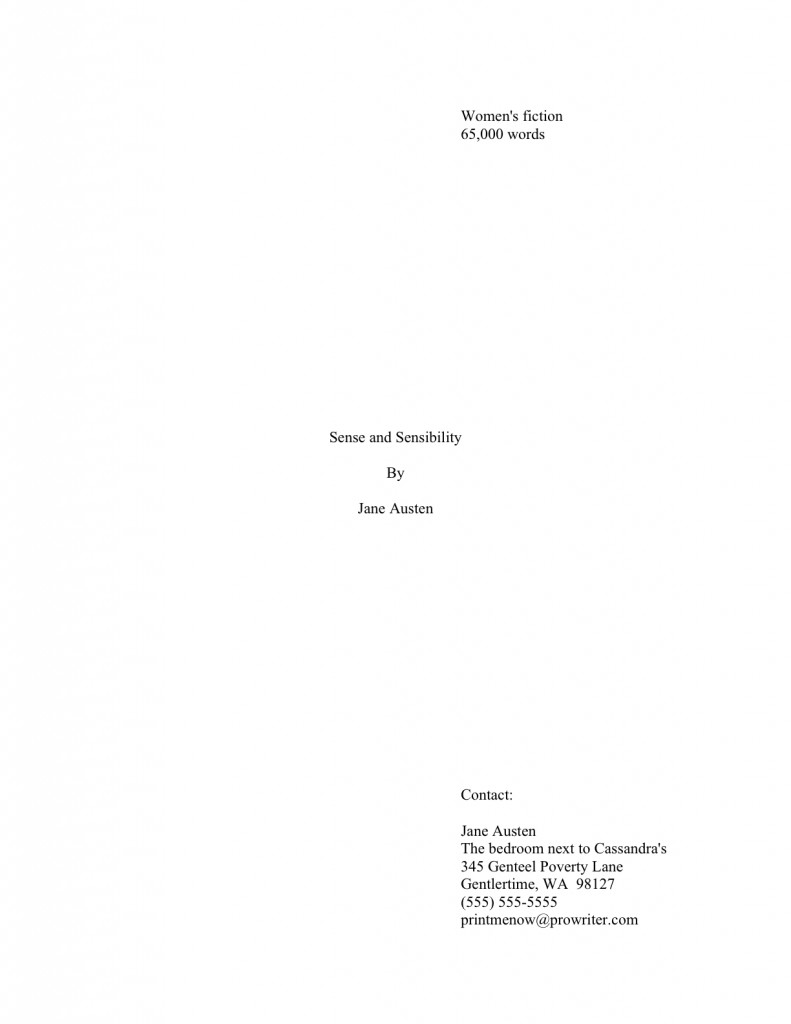

Does that leave you wondering Millicent will notice the quote at all, much less find it obnoxious? I’m guessing she will, because this is was what she was expecting to see:

Actually, that was sort of a red herring — that wasn’t precisely what she expected. Pop quiz: did you catch the vital piece of information he left off his title page?

If you said that Eeyore neglected to include the book category on the second example, award yourself a pile of thistles. (Hey, that’s what he would have given you.) His title page should have looked like this:

And yes, I am going to keep showing you properly-formatted title pages until you start seeing them in your sleep; why do you ask? Take a moment to compare the third example with the first: the quote in the first example is going to stand out to Millicent like the nail in a certain critter’s tail, isn’t it?

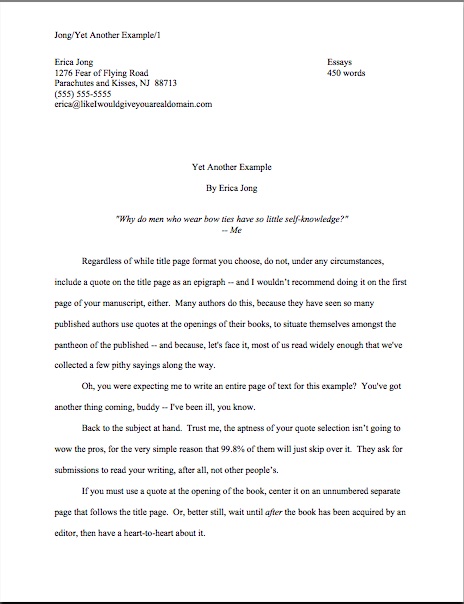

Other submitters choose to eschew the title page route in order to place an epigraph on the first page of text. The result is immensely cluttered, by anyone’s standards — especially if the submitter has made the very common mistake I mentioned in my discussion of title pages last time, omitting the title page altogether and cramming all of its information onto page 1:

Where did all of our lovely white space go? Into quoting, partially.

The last popular but ill-advised way to include an introductory epigraph is to place it on a page all by itself in the manuscript, between the title page and the first page of text. In other words, as it might appear in a published book:

What’s wrong with this, other than the fact that Poe died before our boy D.H. wrote Sons and Lovers? Chant it with me now, everyone: a manuscript is not supposed to look just like a published book; it has its own proper format.

At best, Millicent is likely to huffily turn past this page unread. At worst, she’s going to think, “Oh, no, not another writer who doesn’t know how to format a manuscript properly. I’ll bet that when I turn to page one, it’s going to be rife with terrible errors.” Does either outcome sound especially desirable to you?

I thought not. So what should an epigraph-insistent submitter do?

Leave it out, of course — weren’t you listening before?

But if it is absolutely artistically necessary to include it, our pal Mssr. Poe actually wasn’t all that far off: all he really did wrong here was include a slug line. The best way to include an introductory epigraph is on an unnumbered page PRIOR to page 1. On that unnumbered page, it should begin 12 lines down and be centered. But I’m not going to show you an example of that.

Why? Because I really, truly would advise against including an epigraph at all at the submission stage. Just in case I hadn’t made that clear.

That doesn’t mean you should abandon the idea of epigraphs altogether, however. Squirrel all of those marvelous quotes away until after you’ve sold the book to a publisher — then wow your editor with your erudition and taste. “My,” the editor will say, “this writer has spent a whole lot of time scribbling down other authors’ words.”

Or, if you can’t wait that long, land an agent first and wow her with your erudition and taste. But don’t be surprised if she strongly advises you to keep those quotation marks to yourself for the time being. After all, she will want the editor of her dreams to be reading your writing, not anyone else’s, right?

If you are submitting directly to a small press, do be aware that most publishing houses now place the responsibility for obtaining the necessary rights squarely upon the author. If you include epigraphs, editors at these houses will simply assume that you have already obtained permission to use them. Ditto with self-publishing presses.

This expectation covers, incidentally, quotes from song lyrics, regardless of length.

I’m quite serious about this. If you want to use a lyric from a song that is not yet in the public domain, it is generally the author’s responsibility to get permission to use it — and while for other writing, a quote of less than 50 consecutive words is considered fair use, ANY excerpt from an owned song usually requires specific permission, at least in North America. Contact the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (ASCAP) for assistance in making such requests. (For a very funny first-hand view of just what a nightmare this process can be, please see FAAB Joel Derfner’s guest post on the subject.)

Have I talked you out of including an epigraph yet — particularly an excerpt from a copyrighted song, like Alice Walker’s? I hope so.

I know that it hurts to cut your favorite quote from your manuscript, but take comfort in the fact that at the submission stage, no cut is permanent. Just because you do not include your cherished quotes in your submission does not mean that they cannot be in the book as it is ultimately published.

Contrary to what 99% of aspiring writers believe, a manuscript is a draft, not a finished work. In actuality, nothing in a manuscript is unchangeable until the book is actually printed — and folks in the industry make editing requests accordingly.

In other words, you can always negotiate with your editor after the book is sold about including epigraphs. After you have worked out the permissions issue, of course.

There’s nothing like a good practical example to clarify things, is there? More follow next time. Keep noticing the beauty in the everyday, everybody, and keep up the good work!