I read in the paper this morning that only one American veteran of the War to End All Wars — World War I’s armistice is why there’s no mail delivery today, in case any of you stateside had been wondering; it’s also why the banks are closed and all of those mattresses are on big, big sale — was still alive and kicking. He’s 108 years old.

And I’ve been steeped in the life literary for so long that my very first thought was, “Gee, I wonder if anyone’s approached him about dictating a memoir. I could practically write the book proposal off the top of my head!” rather than, “How nice that he’s gotten to see so many Veterans’ Days go by; I wonder if he was annoyed when they changed it from Armistice Day,” or even “Gee, sir, thank you for helping show the world that trench warfare was a really, really stupid idea.”

Fair warning: this could happen to you, too. Just keep on writing those books.

My father was a child during WWI (no, I’m not that old; he was when he had me); he recalled the day when the local doughboys came home. He would tell vivid anecdotes about watching protest marches in the streets, rationing, how his mother’s views on military service varied markedly as her only son approached draft age.

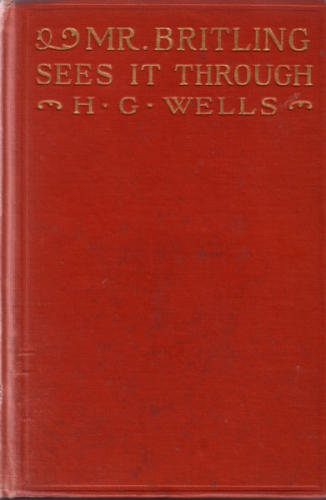

It was from him, and not from my school’s history books, that I learned that here in the States, it had been quite an unpopular war; years later, it was his stories of the home front that I would contrast with H.G. Wells’ brilliant 1916 description of the British home front, MR. BRITLING SEES IT THROUGH. (In case you missed my oh-so-subtle plug for it above, here goes: if you’ve never read it and are even remotely interested in how human beings respond to their countries’ being at war, you might want to have the Furtive Non-Denominational Gift-Giver* add it to his list for you this year. I just mention.)

I love this book — and not just because it’s a genuinely thoughtful, well-written work by an author whose non-science fiction writings have since his death fallen into undeserved obscurity. Which is a bit surprising, since Wells’ social novels were so very popular around World War I.

How steep has his plummet from notice as a mainstream novelist been? Well, let me ask you: were you aware that he coined the phrase the war to end all wars?

MR. BRITLING SEES IT THROUGH is also one of the great examples of why write what you know is often such great advice. What writer living in wartime — and when aren’t we all? — would not resonate with a paragraph like this:

The battle of the Marne passed into the battle of the Aisne, and then the long lines of the struggle streamed north-westward until the British were back in Belgium failing to clutch Menin and then defending Ypres. The elation of September followed the bedazzlement and dismay of August into the chapter of forgotten moods; and Mr. Britling’s sense of the magnitude, the weight and duration of this war beyond all wars, increased steadily. The feel of it was less and less a feeling of crisis and more and more a feeling of new conditions. It wasn’t as it had seemed at first, the end of one human phase and the beginning of another; it was in itself a phase. It was a new way of living. And still he could find no real point of contact for himself with it at all except the point of his pen. Only at his writing-desk, and more particularly at night, were the great presences of the conflict his. Yet he was always desiring some more personal and physical participation.

Not that why write what you know is as self-explanatory and all-encompassing a piece of advice as many writing teachers seem to think. As those of you who have been hanging around Author! Author! for a good, long while are already aware, I’m no fan of one-size-fits-all writing advice — beyond the basic rules of grammar and formatting restrictions, of course. What works in one genre will not necessarily work in another, after all, nor are the stylistic tactics that made ‘em swoon in 1917 or 1870 particularly likely to wow an agent or editor now.

Doubt that, all of you Dickens-huggers out there? Okay, I dare you: try submitting the paragraph above to an agent or editor now. Even if it actually made it onto an agent’s desk — if, that is, Millicent the agency screener didn’t reject it out of hand for the repetitive word use, over-employment of the passive voice (pretty much universally regarded as bad writing in submissions now), and misuse of the semicolon (by definition, a semicolon followed by and is redundant, since a semicolon is implicitly an abbreviation for comma + and) — the sheer number of semicolons within this short paragraph would automatically raise both eyebrows and questions about the intended target audience. If the book in question were, say, a mainstream novel rather than literary fiction or an academic book, all of those semicolons would seem, well, a bit much.

But then, in Wells’ day, novelists had the luxury of being able to write about current events in the reasonable expectation that the book would be in readers’ hands before today’s headlines were distant memories. He was able to write about the home front while the war was still going on — and not merely as a journalist.

Now, journalists, politicians, and academics who have studied the field for twenty years are generally the only ones who can reliably pitch a book on what’s happening right now socio-politically with success — and even then, only as nonfiction. Partially, this is a matter of platform (if you write any kind of nonfiction whatsoever and don’t know what that is, run, don’t walk to the PLATFORM category on the archive list at the lower right-hand side of this page), but it’s also a symptom of how much longer it takes to get a book into print.

Not only after it’s written and found an agent, but thereafter.

How much longer, you ask with fear and trembling? Well, let’s assume that the manuscript is already absolutely clean (the professional term for completely free of typos and other errors; few submissions are completely clean, despite my perpetual nagging in this forum) and the agent is completely happy with it (also rare for a submission; agents often request extensive revisions before sending anything out). The agency will almost certainly have a backlog of manuscripts ready to go, so yours will have to wait its turn.

When its time does roll around, the agent may send out anywhere from one to a dozen copies to different editors, depending upon the agency’s preferred submission policy. If it’s a single submission, the agent will wait until she hears back from the editor before sending out the next; if she’s chosen to make multiple simultaneous submissions, she may send out a copy to another editor when a rejection arrives.

Or she may not; my agency, for instance, does submissions in waves, pausing sometimes six months before sending out the next set of manuscripts to the next set of editors. This is not at all an unusual practice.

Take a nice, deep breath. You’ll feel better.

So it’s fairly common for an agent to be circulating a manuscript, even a very good one, not to sell it for a year, year and a half, two. That’s an awfully long time, if any portion of the book’s market appeal relies upon relevance to current events; it’s not altogether surprising, then, that agents so often tell aspiring writers of up-to-the-minute stuff that the book will be dated too quickly to render marketing it worthwhile.

Why, you ask? Um, are you sitting down?

Comfy? Here goes: even if the manuscript in question was absolutely timely when it was written, and remains absolutely timely a year or two later, when the agent manages to sell it to an editor at a publishing house, to remain relevant, the same world conditions will have to prevail a year or more later, when the book actually becomes available for sale to readers.

This is one reason, in case any of you submitters have been wondering, that writers who go batty if an agent who requested a manuscript doesn’t respond right away strike the pros as potentially difficult to work with: the agented life is largely one of waiting for something to happen. So if a writer walks into it expecting that everyone who comes in contact with his manuscript will instantly drop everything else in order to read it, he’s going to expend HUGE amounts of energy feeling his work is being ignored.

It isn’t; the process just takes a while.

And that — phew! — brings me back to my overarching topic du jour, the passage of time in the submission process. I’ve been meaning to get back to it for a while, since I receive so many private questions about it. (Why private? Beats me. For some reason that defies understanding from my side of the agent-landing process, I very frequently receive e-mailed questions from submitters who are absolutely convinced that no other aspiring writer in North America has ever been in their particular situation — or so I surmise from the fact that so many of them are unwilling to post the questions here, lest an agent recognize the situation.) For the next few weeks, however, I’m going to be tackling that backlog of readers’ questions, so let’s launch right into it.

A periodic reader who, for reasons best known to himself, has requested anonymity, has brought up the perennial issue of turn-around times on submissions. Since I know that many aspiring writers share his concerns, I have changed the identifiable information to preserve the secret identities of both author and agent:

Agent Pablo Picasso (how’s that for an undetectable pseudonym?) requested the full manuscript and I sent it three weeks ago. How long should I wait for him to make contact? Is it all right for me to call? I don’t want to pressure him, but I am desperate to move forward with the project. Oh, the anxiousness. Ah, the sleepless nights. I have never wanted anything more than to be a published author…

I know there are no set timelines for responses and such, but roughly how long should I wait before moving on?

Here’s the short answer, Mystery Reader (another undetectable cover): don’t even think about following up for 6-8 weeks (or at least a week past the agency’s stated turn-around time, and when you do, DON’T CALL; e-mail or write.

In the meantime, Mysterious One, you should most definitely be moving on now: get back to your writing projects. You might even consider sending out a few more queries, just in case. And if any other agent has requested materials, you should already have sent them.

Well, that cleared everything up, didn’t it? Moving right along…

Just kidding. On to the long answer: three weeks is most definitely not a long time to wait for a response from an agent on a submission. I would be extremely surprised if you heard back in under a month. But if ol’ Pablo didn’t give you a timeframe in the request for materials (as many agents do), 6-8 weeks is average.

I can feel heart rates rising all over the English-speaking world. “But Anne,” those of you either on the cusp of sending out manuscripts or waiting breathlessly to hear back from agents protest, “Mystery Reader said that Pablo Picasso asked for the full manuscript — that must mean he was really, really interested, right? Surely not hearing back indicates that he’s lost interest, right?”

Actually, not necessarily, and not even probably. What not hearing back generally means is either (a) nobody at the agency has read it yet, (b) it hasn’t made it past Millicent, or (c) it did make it past Millicent, but the agent hasn’t had time to get to it.

Don’t pull that long face; it’s nothing personal. Long-time readers, pull out your hymnals and sing along with me: because a request for pages does not equal a promise to drop everything the second those materials turn up at the agency.

Like so many other aspects of the biz, an agent requesting materials will expect a serious aspiring writer to be familiar enough with the biz to be aware of that. Consequently, badgering an agent interested in your work will definitely NOT get him or her to read faster — in fact, it sometimes produces the opposite effect — it is not a good course to pursue. Most agents will regard follow-up calls or too-soon e-mails as a sign that the prospective client does not understand how the business works.

Which is not an impression you want to give an agent you would like to sign you. Why? Well, it tends to translate, in their minds, into a client who is going to require more attention at every step of the process. While such clients are often rewarding on many levels, they are undoubtedly more expensive for the agency to handle, at least at first.

Think about it: Pablo Picasso, like every other reputable agent in the country, makes his living by selling books to publishing houses. This means a whole lot of phone calls, meetings, and general blandishment, all of which takes a lot of time, in order to make sales.

So which is the more lucrative way to spend his time, hard-selling a current client’s terrific novel to a wavering editor or taking anxious phone calls from a writer he has not yet signed?

Uh-huh. Trust me, Pablo Picasso (too obvious a pseudonym?) already knows that you want to be published more than anything else in the world; unfortunately, telling him so will not impress him more.

How does he know Mystery Writer’s innermost feelings? Because he deals with writers all the time — and this is such a tough business to break into that the vast majority of those who make it to the full-manuscript request are writers who want to be published more than anything else in the world.

Mystery Reader, you will be a much, much happier human being if you bear this in mind. I can assure you that an agent who receives 800 or 1000 queries per week from glorious dreamers does not have the luxury of forgetting it.

You’re certainly not alone in thinking of your query or submission as if it emits a come-hither glow in the agency’s mail room, however. The average aspiring writer, bless his or her heart, tends to forget that the dream of publication is a fairly common one — thus that huge volume of queries through which Millicent sifts five days per week, each of which is presumably from someone who yearns for publication.

Let’s face it, querying and submission are FAR too hard on the heart (not to mention the wrists) to keep doing if you don’t want success that much, right?

The very intensity of the longing can sometimes blur an aspiring writer’s view of the agent-finding process — or indeed, the period when one’s agent is shopping one’s book around to editors. Even the most successful author’s career is stuffed to the gills with periods when s/he can do nothing but wait.

And as anyone who has ever been a teenager with a crush can tell you, every minute devoted to waiting for the phone to ring, for That Special Someone to declare his intentions, is eighteen times longer than a normal minute. Nothing extends a second like not having someone else determine what’s going to happen to you at the end of it.

This is precisely Mystery Reader’s dilemma, I’m afraid. All you can do is wait — at least for 6 weeks or so, or (to trot out my favorite rule of thumb) for twice the turn-around time the agency has listed in an agency guide blurb or on its website.

Which is yet another reason that a prudent submitter should always double-check the agency’s own guidelines before submitting materials. Why? Long-time readers, chant it with me now: there is no hard-and-fast rule that may be applied to every agent at every agency, every time.

This information is usually easily available either on the agency’s website or its listing in one of the standard agency guides. And if either of those sources say anything along the lines of Please do not contact us to make sure we received your materials or We do not respond to submissions that do not interest us, do not even consider waiting around until you hear back from them.

Because you may not.

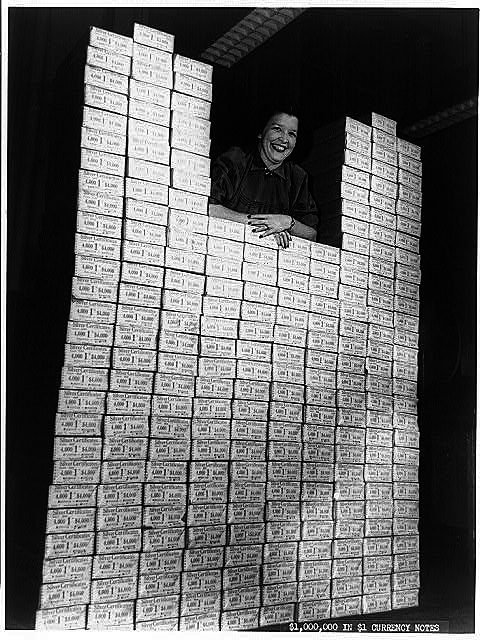

Before anyone starts pouting about it: yes, it would be much, much simpler for aspiring writers everywhere if each and every agency on the face of the earth agreed to adhere to a single standard for turn-around times, but the fact is, there is no incentive for them to do so. Quite the opposite, in fact: a TREMENDOUS amount of paper passes through the average agency’s portals, and yours is almost certainly not the only full manuscript requested by Señor Picasso within the last couple of months. Yours goes into the reading pile after the others that are already there — and if that feels a little unfair now, think about it again in a month, when a dozen more have come in after yours.

And how long it will take our pal Pablo to make his way through that queue can vary not only from agency to agency, but month to month, or even week to week. One day’s workload for an agent may be quite different from another, and it’s not as though a really successful agent will have inviolable reading times built into his work schedule.

In fact, many agents read submissions not at work, but in their off hours. In all probability, yours will not be the only MS sitting next to his couch. Also, in a big agency like Picasso’s (he happens to be an agent I know), it’s entirely possible that before it gets to the couch stage, it will need to be read by one or even two preliminary readers.

Again, all that takes time.

In the meantime, though, you are under no obligation not to query or follow up with any other agent. (See earlier comment about the advisability of sending out a few queries now.) That, too, is SO easy for an excited writer to forget: until you sign an agency contract, you are free to date other people, literarily speaking. And you should.

Really. No matter how many magical sparks there were between the two of you at your pitch meeting, even if Picasso’s venerable eyes were sparkling with book lust, it honestly is in your best interest to keep querying other agents until he antes up a concrete offer. Until that ring is on your finger, keep playing the field.

And where does that leave Mystery Reader in the meantime? Waiting by the phone or mooning by the mailbox, of course. It’s hard to act cool when you want so much to make a connection. Yes, he SAID he would call after he’s read my manuscript, but will he? If it’s been a week, should I call him at the agency, or assume that he’s lost interest in my book? Has he met another book he likes better? Will I look like a publication-hungry slut if I send an e-mail after three weeks of terrifying silence?

Auntie Anne is here to tell you: honey, don’t just sit by the phone; you are not completely helpless here. Get out there and date other agents, so that when that slow-reading Picasso DOES call, you’ll have to check your dance card.

Of course, if another agent asks to see the manuscript, it is perfectly acceptable, even laudable, to drop Mr. Picasso an e-mail or letter, letting him know that there are now other agents checking out your work. For the average agent, this news is only going to make your work seem all the more attractive.

See? I told you it was just like dating in high school.

Even after 6-8 weeks has elapsed, e-mail, instead of calling. The last thing you want is to give the impression that you would be a client who would be calling three times per week. Calling is considered a bit pushy, and it almost certainly won’t get your work read any faster — unlike, say, an e-mail that mentions politely that there is now another agent reading it.

And yes, Agent #1 WILL want you to tell him that immediately. Over and above that, though, all you can do is (sing it out now) WAIT.

Another great reason to keep querying and submitting while Agent #1 is taking his own sweet time getting back to you is the increasingly common phenomenon I mentioned above, agents not responding to queries or even submissions at all. Within the last few years, literally dozens of very talented writers of my acquaintance have had manuscripts out to agents for four, five, or even six months without any response. Requested materials.

This places the writer in a quandary, of course, because from the other side of the country (or the world), how on earth is it possible to tell the difference between a delay caused by a submission’s sitting on an agent’s coffee table, holding up take-out cartons until she has time to read it, one that springs from an unannounced rejection, and one triggered by the manuscript’s having gotten lost in the mail?

For this reason, I used to advise my clients and students to include a self-addressed, stamped postcard with every submission, along with a request in the cover letter (you HAVE been including cover letters with your submissions, haven’t you?) that Millicent would write the date it arrived upon it and pop it in the mail upon opening the packet of requested materials. I historically, this works far, far better than asking for e-mail confirmation, since complying requires far less effort on the part of agency personnel.

Hey, they’re busy. Have you seen that stack of manuscripts Pablo has to read through?

The USPS now offers a much less obtrusive option for making sure your manuscript arrived where it should, and when: Track & Confirm. For a negligible fee, you can receive an e-mail confirming delivery of your package, without anyone at the agency’s having to lift a finger to inform you of it.

Unfortunately, there’s no similar service for e-mailed submissions — and since many agencies that accept e-mailed queries and submissions specifically request in their guidelines that writers not follow up to ask if materials were received. Yet another reason that given the choice, I would always opt for a hard copy submission over an electronic one.

What you SHOULDN’T do whilst waiting for a reply is waste your energy constructing a vivid justification for why the agent of your dreams has not yet gotten back to you — an exercise in creative fantasy in which I’ve seen aspiring writers starting mere hours after dropping the submission into the mail.

Trust me, it won’t help your chances; it will only enervate you.

Let me preemptively take the wind out of the sails of the most common of these middle-of-the-night musings: if you haven’t heard back, it’s not because the agent thinking about it or wants to talk with every other employee in the agency before talking it on; it’s because he hasn’t read it yet.

See why most agents get a bit defensive if a writer calls, demanding to know why it’s taking so long? Much like, if memory serves, teenage boys.

Oh, how I wish we had all outgrown that awkward stage.

Try to think of a slow response in positive terms. At many agencies, a submission has to make it past more than one level of Millicent before making it onto the agent’s desk at all — and yes, Mystery Reader, that’s usually still true even if one has met the agent at a conference. If Millie #1, Millie #2, or the agent had taken a dislike to your manuscript, it would have been stuffed into the SASE right away. (See why it’s fairly safe to assume that if you haven’t yet heard back, it hasn’t been read?) Rejections tend to be quicker than acceptances.

I know that this isn’t exactly the answer you wanted, Mystery Reader, but please, try to chill out for the next month or so. Get working on your next book, because if this goes through, you will want to have it well in motion. Keep approaching other agents, because it can only be good for you if several are clamoring to represent you.

And be very, very proud of yourself for getting to the point in your writing that an agent as prestigious as Pablo Picasso WANTS to read the whole manuscript. He doesn’t ask just anybody on a date, you know.

Believe it or not, if you’re successful in submission, the anxiety of waiting will become almost routine, just one of the many swiftly-alternating moods of the working writer’s career. Try to be patient, and keep up the good work!

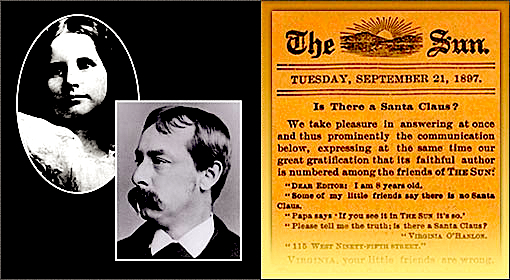

* For the benefit of those of you who weren’t reading this blog regularly throughout holiday seasons past, the Furtive Non-Denominational Gift-Giver (FNDGG) is a jolly elf who regularly graces this page in the winter months, ho, ho, hoing his way toward the end of the year. Better not pout, better not cry — and better get used to hearing about him, because he’s bound to keep cropping up in the months to come.

Those of you who were hanging around the Author! Author! virtual lounge may remember Stan from last year, when he was kind enough to visit with

Those of you who were hanging around the Author! Author! virtual lounge may remember Stan from last year, when he was kind enough to visit with  How can a man die twice?

How can a man die twice?

Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip.

Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip.

PS: don’t forget to check in this weekend for the promised special treat!

PS: don’t forget to check in this weekend for the promised special treat!

PS: don’t forget to tune in on Friday for our end-of-the-week treat!

PS: don’t forget to tune in on Friday for our end-of-the-week treat!