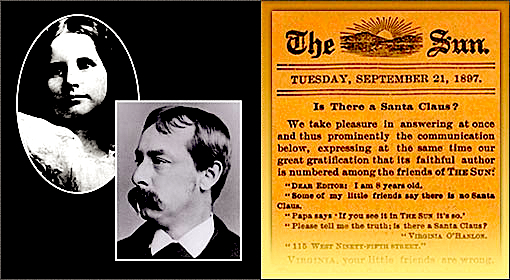

Hot on the heels of yesterday’s ruminations about the ever-changing state of publishing, I happened upon this article about print-on-demand going on in a local independent bookstore. Basically, the buyer picks a book off an extensive list (most of whose items are in the public domain, neatly side-stepping the whole how-does-the-writer-get-paid issue), a clerk sets up an industrial print-and-binding machine, and violà! Roughly 18 minutes later, the customer is holding a physical copy of a 19th-century novel that’s been out of print for decades.

Progress, or just another sled on the slippery slope toward authors not being paid for their writing at all? What do you think?

While you’re pondering that Gordian knot, let’s revisit yesterday’s subject, politeness as a scene-killer. In fact, while we’re already on the topic, let’s make a day of it and take a guided tour of standard agents’ euphemisms for being bored by a submission.

Why should every reviser worth her proverbial salt be aware of these euphemisms, you ask? A couple of reasons, and good ones. First, as I have pointed out several times throughout our recent discussion of self-editing tactics, writers of first drafts often don’t actively consider during the composition process the possibility that their stories or arguments, while no doubt beautifully written and new to them, may be rather similar to other stories or arguments currently making the rounds of agencies. Particularly — and it pains me to say this, but it is true — if the story or argument in question happens to bear even the slightest to a bestseller that came out any time within the last decade.

Trust me, no matter how slight the familial resemblance between your novel and, say, THE DA VINCI CODE, Millicent’s seen so many iterations of the latter come across her desk in recent years that a similar paragraph or, heaven help us, 3-page chapters may well strike her as the identical twin of something she’s seen 20,000 times before. Thus that latte Millicent, the agency screener in my examples, keeps chugging, regardless of the danger to her oft-burnt tongue. She has to do something to stay awake as she’s leafing through the fifty submissions before yours turns up to brighten her day and gladden her heart.

Which leads me to the second reason: boring Millicent is one of the most common reasons for rejection at both the submission and query stages, yet interestingly enough, when one hears agents giving advice at conferences about how to guide manuscripts through the submission process relatively unscathed, the rather sensible admonition, “Whatever you do, don’t bore me!” is very seldom heard. Partially, I think, this is due to people in the industry’s reluctance to admit in public just how little they read of most manuscripts before rejecting them.

How little? Long-time members of the Author! Author! community, chant it with me now: the average submission is rejected on page 1. Sometimes in paragraph 1, or even sentence 1. As with query letters, submissions arrive at agencies in sufficient volume that screeners are trained to find reasons to reject them, rather than reasons to accept them.

Why isn’t this fact shouted from the rooftops and hung on banners from the ceilings of writers’ conferences, since being aware of it could only help everyone concerned, including Millicent? Well, having met my share of conference organizers, I would imagine it has something to do with not wanting to discourage attendees into giving up. It is a genuinely depressing state of affairs, after all, especially for those who have been querying and submitting for a while, and I can understand not wanting to be standing in a room with 400 writers hearing this hard fact for the first time.

Also, whenever I HAVE heard the news broken at a conference, the audience tends to react, well, a trifle negatively. Which is perfectly understandable, since from an aspiring writer’s point of view, such a declaration almost invariably means one of two things: either the agent or editor is a mean person who hates literature (but loves bestsellers), or that the admitter possesses an attention span that would embarrass most kindergarteners and thus should not be submitted to, queried, or even approached at all.

Either way, writers tend to react as though the pro were admitting a personal failing. That, too, tends not to help anybody concerned.

Actually, the prevailing assumptions about Millicent’s notoriously short attention span aren’t entirely fair. She may have a super-short of attention span for the opening pages of submissions, but she’s been known to pore over the 18th draft of an already-signed writer whose work she loves three times over. So have her boss, the agent, and the editor to whom they sell their clients’ work. However, since none of the three want to encourage submitters to bore them, they might not be all that likely to admit the latter before a bunch of aspiring writers at a conference.

Something else you’re unlikely to hear: that on certain mornings, the length of time it takes to bore a screener is substantially shorter than others, for reasons entirely beyond the writer’s control. I cast no aspersions and make no judgments, but they don’t call it the city that never sleeps for nothing, you know.

But heaven forfend that an agent should march into a conference and say, “Look, I’m going to level with you. If I’m dragging into the office on three hours of sleep, your first page is going to have to be awfully darned exciting for me even to contemplate turning to the second. Do yourself a favor, and send me an eye-opening first few pages, okay?”

No, no, the prevailing wisdom goes, if the reader is bored, it must be the fault of the manuscript – or, more often, with problems that they see in one manuscript after another, all day long. (“Where is that nameless intern with my COFFEE?” the agent moans.)

As it turns out, while the state of boredom is generally defined as a period with little variation, agents have been able to come up with many, many reasons that manuscripts bore them. Presumably on the same principle as that often-repeated truism about Arctic tribes having many words for different types of snow: to someone not accustomed to observing the variations during the length of a long, long winter, it all kind of looks white and slushy.

Here are a few of the most popular — and don’t be surprised if they seem a trifle familiar, long-time readers. I cribbed them from the extremely-useful-but-utterly-horrifying list of reasons agents give for rejecting submissions on page 1 we discussed in last January’s HOW NOT TO WRITE A FIRST PAGE series (conveniently gathered under the category of the same name on the archive list at the bottom right-hand side of this page, incidentally). They include :

(1) Not enough happens on page 1.

(2) Where’s the conflict?

(3) The story is not exciting.

(4) The story is boring. (I know: not a very subtle euphemism, but bear with me here.)

(5) Repetition on pg. 1 (!)

(6) Took too many words to tell us what happened.

(7) The writing is dull.

(8) I didn’t care enough about the protagonist and/or his situation to muster the effort to turn to page 2.

Sensing a pattern here? Now, to those of us not lucky enough to be screening a hundred submissions a day, that all sounds like variations on snow, doesn’t it? But put yourself in Millicent’s snow boots for a moment: imagine holding a job that compels you to come up with concrete criteria to differentiate between not exciting, boring, and I’m just not interested.

This probably wasn’t the glamour she expected when she first landed the job at the agency.

Most of these are pretty self-explanatory, but not enough happens on page 1 might confuse, as it is often heard in its alternative incarnation, the story took too long to start. Many a wonderful manuscript doesn’t really hit its stride until page 4 — or 15, or 146. And you’d be amazed at how often a good writer will bury a terrific first line for the book on page 10.

That’s not criticism; it’s just a fact. Unfortunately, neither Millicent, her cousin Maury who screens manuscripts for editors at a major publishing house, nor their Aunt Mehitabel, the inveterate contest judge, tends to have the time or the patience to wait for a slow-moving manuscript to pick up momentum.

The screening process is not, to put it mildly, set up to reward brilliance that takes a little while to warm up — and that’s not merely a matter of impatience on the reader’s part. Remember, that burnt-tongued screener racing through manuscripts will have to write a summary of any manuscript she recommends to her boss. So will Maury. Even Mehitabel will have to jot down a little something in order to pass a contest entry on to the finals round.

Think about it for a moment: how affectionate are any of them likely to feel toward a story that doesn’t give her a solid sense of what the story is about by the end of page 1? Please, for the sake of their aching heads and bloodshot eyes, give the reader a sense of who the protagonist is and what the book is about quickly.

Yes, even if you are convinced in the depths of your creative heart that the book in its published form should open with a lengthy disquisition on philosophy instead of plot. Remember, manuscripts almost always change between when an agent picks them up and when the first editor sees them, and then again before they reach publication. If you make a running order change in order to render your book a better grabber for Millicent on page 1, you probably will be able to change it back.

Or at least have a lovely long argument with your future agent and/or editor about why you shouldn’t. In the meantime, you might want to revise those early pages with an eye to getting on with it.

Speaking of unseemly brawls, where’s the conflict? is an exceptionally frequent reason for rejecting submissions — and not merely on page 1. In professional reader-speak, this means that the opening is well-written, but lacks the dramatic tension that arises from interpersonal friction (or in literary fiction, intrapersonal friction).

Or, to put it less technically, it’s not clear to Millicent what is at stake, who is fighting over it, and why the reader should care. Oh, you may smile at the notion of cramming that much information, which is really the province of a synopsis or pitch, into the first page of a manuscript, but to be blunt about it, Millicent’s going to need all of that information to pitch the book to her higher-ups at the agency. Giving her some immediate hints about where the plot is going is thus a shrewd strategic move.

Perhaps more to the point, while that’s going to be problematic at any point in a submission or contest entry, if it’s the prevailing condition at the bottom of page 1, our Millie tends, alas, to revert by default to #8, I didn’t care enough about the protagonist and/or his situation to muster the effort to turn to page 2. Next!

Where’s the conflict? has been heard much more often in professional readers’ circles since writing gurus started touting using the old screenwriter’s trick of utilizing a Jungian heroic journey as the story arc of the book. Since within that storyline, the protagonist starts out in the real world, not to get a significant challenge until the end of Act I, many novels put the conflict on hold, so to speak, until the first call comes.

(If you’re really interested in learning more about the hero’s journey structure, let me know, and I’ll do a post on it. Or you can rent one of the early STAR WARS movies, or pretty much any US film made in the 1980s or 1990s where the protagonist learns an Important Life Lesson. Basically, all you need to know for the sake of my argument here is that this ubiquitous advice has resulted in all of us seeing many, many movies where the character where the goal is attained and the chase scenes begin on page 72 of the script.)

While this is an interesting way to structure a book, starting every story in the so-called normal world tends to reduce conflict in the opening chapter, by definition: according to the fine folks who plot this way, the potential conflict is what knocks the protagonist out of his everyday world.

I find this plotting assumption fascinating, because I don’t know how reality works where you live, but around here, most people’s everyday lives are simply chock-full of conflict. Gobs and gobs of it. And if you’re shaking your head right now, thinking that I must live either a very glamorous life or am surrounded by the mentally unbalanced, let me ask you: have you ever held a job where you didn’t have to work with at least one person who irritated you profoundly?

Having grown up in a very small town, my impression is that your garden-variety person is more likely to experience conflict with others on the little interpersonal level in a relatively dull real-life situation than in an inherently exciting one — like, say, a crisis where everyone has to pull together. Having had the misfortune to work once in an office where fully two-thirds of the staff was going through menopause, prompting vicious warfare over where the thermostat should be set at any given moment, either hot enough to broil a fish next to the copy machine or cool enough to leave meat, eggs, and ice cubes lying about on desks for future consumption, let me tell you, sometimes the smallest disagreements can make for the greatest tension.

I know, I know: that’s not the way we see tension in the movies, where the townsfolk huddled in the blacked-out supermarket, waiting for the prehistoric creatures to attack through the frozen food section, suddenly start snapping at one another because the pressure of anticipation is so great. But frankly, in real life, people routinely snap at one another in supermarkets when there aren’t any prehistoric beasts likely to carry off the assistant produce manager, and I think it’s about time more writers acknowledged that.

I’m bringing this up for good strategic reasons: just because you may not want to open your storyline with the conflict of the book doesn’t necessarily mean that you can’t open it with a conflict. Even if you have chosen to ground your opening in the normal, everyday world before your protagonist is sucked up into a spaceship to the planet Targ, there’s absolutely no reason that you can’t ramp up the interpersonal conflict on page 1.

Or, to put it a trifle less delicately, it will not outrage the principles of realism to make an effort to keep that screener awake throughout your opening paragraphs. Or, indeed, on any page of your manuscript.

What was that shopworn industry truism again? Oh, yes: in a novel or memoir, there should be conflict on every single page.

Do I spot some hesitantly raised hands out there, perhaps ones that have been waving in the air since I posted yesterday? “But Anne,” some courteous souls protest, “conflict to me equals fighting, and I’m trying to show that my protagonist is a normal person, a nice one that the reader will grow to love. How do I present my sweet, caring protagonist as likable if she’s embroiled in a conflict from page 1? Is it okay to have the conflict going on around her in which she doesn’t actually get involved?”

Ah, you’ve brought up one of the classic aspiring novelist’s misconceptions, courteous protesters, one that’s shared by many a memoirist: the notion that what makes a human being likable in real life will automatically render a fictionalized version of that person adorable. It’s a philosophy particularly prevalent in first-person narratives. I can’t even begin to estimate the number of otherwise well-written manuscripts where the primary goal of the opening scene(s) is apparently to impress the reader with the how nice and kind and just gosh-darned polite the protagonist is.

Butter wouldn’t melt in any of their mouths, apparently. As charming as such people may be when one encounters them in real life, from a professional reader’s point of view. they often make rather irritating protagonists, for precisely the reason we’re discussing today: they tend to be conflict-avoiders.

Which can render them a trifle, well, dull on the page. Since interpersonal conflict is the underlying basis of drama (you might want to take a moment to jot that one down, portrayers of niceness), habitually conflict-avoiding protagonists tend to stand in the way of both plot and character development. Instead of providing the engine that moves the plot forward, they keep throwing it into neutral, or even reverse, in an effort to keep tempers from clashing.

Like protagonists who are poor interviewers, the conflict-shy have a nasty habit of walking away from potentially interesting scenes that might flare up, not asking the question that the reader wants asked because it might offend another of the characters, or even being just so darned polite that their dialogue doesn’t add anything to the scene other than conveying that they have some pretty nifty manners.

These protagonists’ mothers might be pleased to see them conducting themselves so well, but they make Millicent want to tear her hear out.

“No, no, NO!” the courteous gasp. “Polite people are nice, and polite people really do talk courteously in real life! How can it be wrong to depict that on the page?”

Oh, dear, how to express this without hurting anyone’s feelings…have you ever happened to notice just how predictable polite interchanges are? As I mentioned last time, they’re generic; given a specific set of circumstances, any polite person might say precisely the same things — which means that if the reader happens to have been brought up to observe the niceties, or even knows someone who has, s/he can pretty much always guess what a habitually polite character will say, and sometimes do, in the face of plot turns and twists.

And predictability, my friends, is one of the most efficient dramatic tension-killers known to humankind.

Don’t believe me? Okay, take a gander at this gallant conversation in a doorway:

“Oh, pardon me, James. I didn’t see you there. Please go first.”

“Not at all, Cora. After you.”

“No, no, I insist. You reached the doorway before me.”

“But your arms are filled with packages. Permit me to hold the door for you, dear lady.”

“Well, if you insist, James. Thank you.”

“Not at all, Cora. Ah-choo!”

“Bless you.”

“Thanks. Please convey my regards to your mother.”

“I’m sure she’ll be delighted. Do send my best love to your wife and seventeen children. Have a nice day.”

“You, too, Cora.”

Courteous? Certainly. Stultifying dialogue? Absolutely.

Now, I grant you that this dialogue does impress upon the reader that James and Cora are polite human beings, but was it actually necessary to invest 6 lines of text in establishing that not-very-interesting fact? Wouldn’t it be more space-efficient if the author had used that space SHOWING that these are kind people through action? (“My God, Cora, I can’t believe you risked your life saving that puppy from the rampaging tiger on your way back from your volunteer gig tutoring prison inmates in financial literacy!”)

Or, if that seems a touch melodramatic to you, how about showing dialogue that also reveals characteristics over and above mere politeness? While you’re at it, why not experiment with letting some of that butter in your protagonist’s mouth rise to body temperature from time to time?

“But Anne,” a few consistency-huggers out there shout, “you can’t seriously mean to suggest that I should have my protagonist act out of character! Won’t that just read as though I don’t know what my character is like?”

Actually, no — in fact it can be very good strategy character development. Since completely consistent characters can easily become predictable (case in point: characters on sitcoms, who often learn Important Life Lessons in one week’s episode and apparently forget them by the following episode), many authors choose to intrigue their audiences by having their characters do or say something off-beat every so often. Keeps the reader guessing — which is a great first step toward keeping the reader engaged.

And don’t underestimate the charm of occasional clever rudeness for revealing character in an otherwise polite protagonist. Take a look at this probably apocryphal but widely reported doorway exchange between authors Clare Boothe Luce and Dorothy Parker, and see if it doesn’t tell you a little something about the characters involved:

The two illustrious ladies bumped into each other at the entrance to the theatre. As it was an opening night performance and the two were well known to be warm personal enemies, a slight hush fell over the crowd around them.

In the face of such scrutiny, Mrs. Luce tried to rise to the challenge. “Age before beauty,” she told Mrs. Parker, waving toward the door.

“And pearls before swine,” Mrs. Parker allegedly replied, sailing in ahead of her.

Polite? Not particularly. But aren’t they both characters you would want to follow through a plot?

“Okay,” my courteous questioners admit reluctantly, “I can see where I might want to substitute character-revealing dialogue for merely polite chat, at least in my opening pages, to keep from boring Millicent. But you haven’t answered the rest of my question: how can I make my protagonist likable if she’s embroiled in a conflict from page 1? What if I just show conflict going on around her, without her, you know, getting nasty?”

For polite people, you certainly ask pointed questions, courteous ones: it means you’re starting to get the hang of interesting dialogue. As you have just illustrated, one way that a protagonist can politely introduce conflict into a scene is by pressing a point that another party to the conversation wants to brush off.

Nasty? Not at all. Conflictual? Definitely.

Not all conflict entails fighting, you see. Sometimes, it’s mere disagreement — or, in the case of a protagonist whose thoughts the reader hears, silent rebellion. Small acts of resistance can sometimes convey a stronger sense of conflict than throwing an actual punch. (For more suggestions on heightening conflict, please see the CONFLICT-BUILDING category on the list at right.)

When in doubt about whether the conflict is sufficient to keep Millicent’s interest, try raising the stakes for the protagonist in the scene. As long as the protagonist wants something very much at that particular moment, is prevented from getting it, and takes some action as a result, changes are that conflict will emerge, at least internally.

Note, please, that I did not advise ramping up the external conflict, necessarily, especially on a first page. In a first-person or tight third-person narrative, where the reader is observing the book’s world from behind the protagonist’s eyeglasses, so to speak, protagonists who are mere passive observers of their own lives are unfortunately common in submissions; if Millicent had a nickel for every first page she read where the protagonist was presented as little more than a movie camera taking in ambient conditions, she wouldn’t be working as a poorly-paid screener; she’d own her own agency.

If not her own publishing house.

Should any of you nonfiction writers out there have been feeling a bit smug throughout this spirited little discussion of protagonist passivity, I should add that the conflict insufficiency problem doesn’t afflict only the opening pages of novels. It’s notoriously common in memoirs, too — as often as not, for the two reasons we discussed above: wanting to make the narrator come across as likable and presenting the narrator as a mere observer of events around him.

Trust me on this one: in both fiction and nonfiction, Millicent will almost always find an active protagonist more likable than a passive one. All of that predictable niceness quickly gets just a little bit boring.

Mix it up a little. Get your protagonist into the game from the very top of page 1.

Then keep her there. Oh, and keep up the good work!

(1) As with the keynote and the elevator speech, most pitchers make the mistake of trying to turn the pitch proper into a summary of the book’s plot.

(1) As with the keynote and the elevator speech, most pitchers make the mistake of trying to turn the pitch proper into a summary of the book’s plot. (2) Most pitchers don’t stop talking when their pitches are done.

(2) Most pitchers don’t stop talking when their pitches are done. (3) The vast majority of conference pitchers neither prepare adequately nor practice enough.

(3) The vast majority of conference pitchers neither prepare adequately nor practice enough. (4) Most pitchers harbor an absurd prejudice in favor of memorizing their pitches, and thus do not bring a written copy with them into the pitch meeting.

(4) Most pitchers harbor an absurd prejudice in favor of memorizing their pitches, and thus do not bring a written copy with them into the pitch meeting. (5) Most pitchers don’t realize until they are actually in the meeting that part of what they are demonstrating in the 2-minute pitch is their acumen as a storyteller. If, indeed, they realize it at all.

(5) Most pitchers don’t realize until they are actually in the meeting that part of what they are demonstrating in the 2-minute pitch is their acumen as a storyteller. If, indeed, they realize it at all. (6) Few pitches capture the voice of the manuscript they ostensibly represent.

(6) Few pitches capture the voice of the manuscript they ostensibly represent.  (7) Very few pitches include intriguing, one-of-a-kind details.

(7) Very few pitches include intriguing, one-of-a-kind details.  (8) Most pitchers assume that a pitch-hearer will hear — and digest — every word they say, yet the combination of pitch fatigue and hectic pitch environments virtually guarantee that will not be the case.

(8) Most pitchers assume that a pitch-hearer will hear — and digest — every word they say, yet the combination of pitch fatigue and hectic pitch environments virtually guarantee that will not be the case. (9) Few pitchers are comfortable enough with their pitches not feel thrown off course by follow-up questions.

(9) Few pitchers are comfortable enough with their pitches not feel thrown off course by follow-up questions. (10) Far too many pitchers labor under the false impression that if an agent or editor likes a pitch, s/he will snap up the book on the spot. In reality, they’re going to want to read the manuscript first.

(10) Far too many pitchers labor under the false impression that if an agent or editor likes a pitch, s/he will snap up the book on the spot. In reality, they’re going to want to read the manuscript first. If the agent is interested by your pitch, she will hand you her business card and ask you to send some portion of the manuscript — usually, the first chapter, the first 50 pages, or for nonfiction, the book proposal. If she’s very, very enthused, she may ask you to mail the whole thing.

If the agent is interested by your pitch, she will hand you her business card and ask you to send some portion of the manuscript — usually, the first chapter, the first 50 pages, or for nonfiction, the book proposal. If she’s very, very enthused, she may ask you to mail the whole thing.