Happy International Women’s Day, everybody! As Marianne (a.k.a. Liberty) shows us above, what’s a little wardrobe malfunction when there are goals to be achieved?

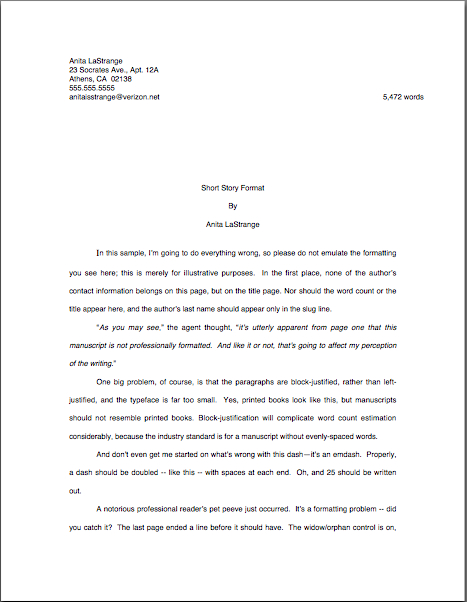

Speaking of malfunctions, for the past few days, I have talking about a series subtle (and not-so-subtle) contest entry snafus that a savvy entrant might want to avoid. To this end, I have asked the entry-happy among you to print out a hard copy of that soon-to-be-sent-out work, give it a thorough read — and subject it to a fairly thorough cross-examination.

Actually, those of you who are not planning to enter a contest anytime soon might want to subject the first chapters of your submissions to this friendly little grilling as well. As I have been mentioning throughout this series, judges often share reading preferences and pet peeves with agents, editors, and their screeners.

In other words, subjecting your opening pages to this set of questions might make Millicent like them more.

Everybody comfy? Okay, let’s resume.

(10) In the chapter itself, is it apparent where this story is going? Is it apparent that it IS going somewhere?

(10) In the chapter itself, is it apparent where this story is going? Is it apparent that it IS going somewhere?

Were the groans I just heard echoing through the ether from those of you who have chosen the contest route over the submission route because agents are so darned well, market-oriented? If so, I sympathize: an aspiring writer does not have to attend many literary conferences to become well and truly sick of hearing that an entry should begin the action from the first line of page one.

Contest judges tend to be a bit more tolerant than the average agency screener, but then, they are substantially more likely to read pages and pages, rather than paragraphs and — well, no, Millicent often doesn’t make it all the way through even the first paragraph of a submission — before making up her mind about the quality of the writing.

However, even in literary fiction competitions, it’s rare to see a fiction entry that doesn’t establish an interesting character in an interesting situation on page one win or place, any more than a nonfiction entry that doesn’t start its argument until page four tends to walk off with top honors.

(11) Is the best opening line (or paragraph) for my work actually opening the text of my entry — or is it buried around page 4?

(11) Is the best opening line (or paragraph) for my work actually opening the text of my entry — or is it buried around page 4?

This question almost always surprises aspiring writers, but in many fiction and nonfiction contest entries (and submissions, if I’m going to tell the truth here), there is a perfectly wonderful opening line or image hidden somewhere in the middle of the first chapter. One way to catch it is by reading the text aloud.

If you find that this is the case with your entry, you might want to take a critical look at the paragraphs/pages/prologue/chapters that currently come before that stellar opening line, image, or scene. Does the early part absolutely need to be there?

That last question made half of you clutch your chests, anticipating an imminent heart attack didn’t it? In most cases, it’s not as radical a surgery as it sounds.

Often, the earlier bits are not strictly necessary to the narrative except as explanatory prologue. Very, very, VERY frequently, opening exposition can go. Particularly when it takes the form of backstory or characters telling one another what they already know in order to bring the reader up to speed — many, if not most, fiction entries overload the first few pages, rather than simply opening the story at an exciting point and filling in background later.

Gradually.

Also, as I mentioned yesterday, there is absolutely no good reason that the version of your chapter that you enter in a contest has to be identical to what you would submit to an agent or editor. Hey, here’s an interesting notion: why not enter a truncated version that begins at that great opening line in a contest and send a non-truncated version to an agent who has requested it, to see which flies better?

(12) Does my synopsis present actual scenes from the book in glowing detail, or does it merely summarize the plot?

(12) Does my synopsis present actual scenes from the book in glowing detail, or does it merely summarize the plot?

Okay, out comes the broken record again: the synopsis, like everything else in your contest entry, is a writing sample, every bit as much. Make sure it demonstrates to the judges that you can WRITE — and that you are professional enough to approach the synopsis as a professional necessity, not a tiresome whim instituted by the contest organizers to satisfy some sick, sadistic whim of their own.

Yes, Virginia, even in those instances where length restrictions make it quite apparent that there is serious behind-the-scenes sadism at work.

Don’t worry about depicting every twist and turn of the plot — just strive to give a solid feel of the mood of the book and a basic plot summary. Show where the major conflicts lie, introduce the main characters, interspersed with a few scenes described with a wealth of sensual detail, to make it more readable.

Oh, and try not to replicate entire phrases, sentences, or — sacre bleu! — entire paragraphs from the entered chapter in the synopsis or vice versa. Entries exhibit this annoying trait all the time, and believe me, judges both notice it and find it kind of insulting that an entrant would think that they WOULDN’T notice it. (Millicent usually shares this response, incidentally.)

Listen: the average contest entry, even in a book-length category, is under 30 pages. You’re a talented enough writer not to repeat yourself in that short an excerpt, aren’t you?

(13) Does the chapter I’m submitting in the packet fulfill the promise of the synopsis? Does the synopsis seem to promise as interesting and well-written a book as the chapter implies?

(13) Does the chapter I’m submitting in the packet fulfill the promise of the synopsis? Does the synopsis seem to promise as interesting and well-written a book as the chapter implies?

As I’ve mentioned a couple of times throughout this series, it’s not at all uncommon for the synopsis and chapter tucked into an entry packet to read as though they were written by different people. Ideally, the voice should be similar in both — and not, as is so often the case, a genre-appropriate chapter nestling next to a peevish, why-on-earth-do-I-have-to-write-this-at-all summary.

It’s also not unusual for a synopsis not to make it clear where the submitted chapter(s) will fit into the finished book, especially an entry where the excerpt is not derived from the opening. It’s never, ever a good idea to confuse your reader, especially if that reader happens to have the ability to award your manuscript a prize.

Remember, it’s not the reader’s responsibility to figure out what’s going on in a manuscript, beyond following the plot and appreciating the twists and turns: it’s the writer’s responsibility to make things clear.

(14) Does this entry read like an excerpt from a great example of its book category?

(14) Does this entry read like an excerpt from a great example of its book category?

Okay, I’ll admit it: as a professional reader, I’m perpetually astonished at how few aspiring writers seem to look at their work critically and ask this question. All too often, when I bring it up, the response is a muttered (or even shouted) diatribe about how demeaning it is to think of art in marketing terms.

Yet it’s a perfectly reasonable question to put to any writer who hopes one day to sell his work: like it or not, very few agencies or publishing houses are non-profit institutions. If they’re going to take a chance on a new writer, they will need to figure out how to package her work in order to make it appeal to booksellers and their customers.

Like the industry, contest judges tend to think in book categories, not merely in generalities as broad as fiction, nonfiction, good, bad, marketable, appealing to only a niche market, and unmarketable. So it’s a GOOD thing when a judge starts thinking a paragraph or two into your entry, “Wow, this is one of the best (fill in genre or book category here) I’ve ever seen.”

In fact, at least two judges will pretty much have to produce that particular sentiment for your entry to proceed to the finalist round of any literary contest. Sometimes more.

So if YOU can’t look at your entry and your favorite example of a book in your chosen category and say, “Okay, these two have similar species markings,” you might want to reconsider whether you’ve selected the right category for it. Which brings me to:

(15) Does this entry fit the category in which I am entering it?

(15) Does this entry fit the category in which I am entering it?

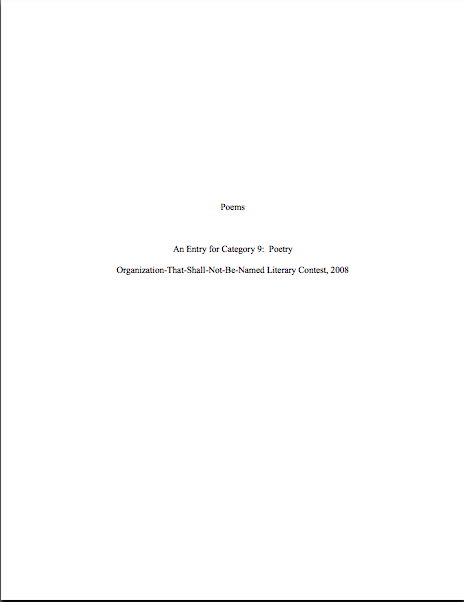

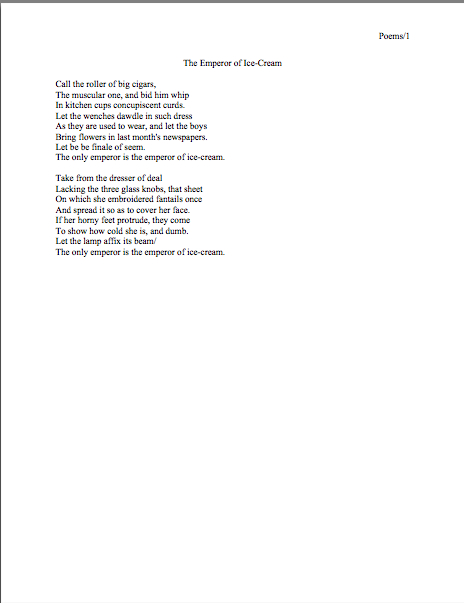

This is a slightly different question from the last one, because as I mentioned earlier in this series, contests do not always categorize writing — particularly fiction — in the same way that the publishing industry does. Just as they will frequently lump apparently unrelated book categories into megacategories (as, for instance, the Contest-That-Shall-Not-Be-Named’s rather perplexing practice of combining mainstream and literary fiction into a single designation), they will often define types of books differently from the pros.

Such ambiguities are not, alas, always apparent from a casual reading of the contest’s promotional materials. Double-, triple-, and quadruple-check the rules, not forgetting to scan contest’s ENTIRE website and entry form for semi-hidden expectations.

If you have the most miniscule doubt about whether you are entering the correct category, have someone you trust (preferably another writer, or at least a good reader with a sharp eye for detail) read over both the contest categories and your entire entry.

Yes, even if you’re reading this a few days before the deadline. Categorization is a crucial decision.

(16) Reading over this again, does this sound like my writing? Does it read like my BEST writing?

(16) Reading over this again, does this sound like my writing? Does it read like my BEST writing?

I know, I know: this last set of questions sounds like an appeal to your writerly vanity, but honestly, it isn’t. As I believe I have mentioned 2300 times within the last few weeks, original voices and premises tend to win good literary contests far more often than even excellent exercises in what we’ve all seen before.

Which is, of course, as it should be.

However, it can be genuinely difficult for a writer to see the difference in her own work, particularly if she happens to be writing in the same book category as her favorite author. Unconscious voice imitation is almost inevitable while one is developing a voice of one’s own.

You should save your blushes here, because virtually every author in the world has done this at one time or another, consciously or unconsciously. It’s only natural to think of our favorite books as the world’s best exemplars of great writing, and for what resembles them in our own work therefore to be better than what doesn’t.

But let’s put writerly ego in proper perspective here: you want to win a literary contest because of what is unique about your work, don’t you, rather than for a dutiful resemblance to a successful author’s best work?

Of course you do — just as you want to be signed by an agent who loves your writing for what is like no one else’s, and sell your book to an editor who doesn’t want to cut and paste until your book reads like the latest bestseller. So it honestly is in your best interests to weed out verbiage that doesn’t sound like YOU.

Think about that a little before you send off your entry — it may seem a tad counter-intuitive, especially to those of you who have taken many classes or attended many writers’ conferences, where one is so often TOLD to ape the latest bestseller. The folks who spout that advice are almost invariably talking about writing a SIMILAR book — which, in their minds, means one that could easily be marketed to the same vast audience, not a carbon copy of the original.

This is a business where small semantic distinctions can make a tremendous difference, my friends. Ponder the paradoxes — and keep up the good work!