I’ve been yammering all week about the importance of reading contest entry requirements as if the fate of the Western world depended upon your following each and every one, but the fact is, in many contests, the rules are far from clear. And no, this is not usually because contest rule designers are just itching to trip you up.

Really. Honest.

In practice, a contest that has been around for a while has probably modified its rules over time — and since in the U.S., the reputable literary contests tend to be run by volunteer organizations, it’s not unheard-of for one board member to add a new rule in response to a specific situation that arose in last year’s contest, another to have inserted two the year before…without anyone concerned realizing that someone needs to go through every so often and make sure that the new collection of rules makes sense.

Which, to their credit, the Contest-That-Shall-Not-Be-Named seems to have done between last year and this. It’s almost as though someone posted a fairly extensive online critique last year — and they responded to it. Entrants everywhere should be happy about this, I think. (But they may be less happy about the fact that this organization has reduced the number of finalists in every category by two from last year.)

But even with the best intentions, contest rules are seldom written so clearly that someone who has absolutely no experience with how the industry likes to see manuscripts could figure out the rules with certainty on the first read-through. In fact, I suspect that if you asked most contest organizers and judges, they would be flabbergasted at the suggestion that writers who haven’t been submitting their work fairly regularly to agents, editors, and magazines would be entering their contest at all.

If you doubt this, take a gander at most literary contests’ rules: most of the time, specific expectations are compressed under terse statements such as, “Submit in industry standard format.”

That should make those of you who have been hanging out on this site for a while feel pretty darned good about yourselves — because, believe me, having some idea what standard format should look like, or even that such a thing exists, places you several furlongs in front of aspiring writers who do not. (If you fall into the latter category, run, don’t walk to the STANDARD FORMAT BASICS category at right.) Because — correct me if your experience contradicts this — this is an industry that tends to conflate lack of professional knowledge with lack of artistic talent.

And that is as true for contest entries as for submissions to agents.

That’s why, in case you have been wondering, I harp on standard format so much here. No one is born aware of how the industry expects to see writing presented, but the rules are seldom shared with those new to the game — and almost never explained in much detail. Admittedly, sometimes one sees the rules asserted in an aggressive do this or fail! tone, but it’s pretty difficult to apply a rule unless you know what it’s for and how it should be implemented.

That’s my feeling about it, anyway. Call me zany, but I would rather see all of you judged on the quality of your WRITING than on whether your manuscript or contest entry adheres to a set of esoteric rules. But unless it does conform to those (often unspoken) rules, it’s just not going to look professional to someone who is used to reading top-of-the-line work.

So try to think of quadruple-checking those rules as the necessary prerequisite to getting a fair reading for your writing — and bear in mind that most judges will expect the author of that winning entry to have been hanging around the industry for a good long time.

The two categories where this expectation is most evident are screenwriting and poetry. Almost any contest that accepts screenplays will use the same draconian standard that the average script agent does: if it’s not in positively the right format (and in the standard typeface for screenplays, Courier), it will be rejected on sight.

Now, I’m going to be honest with you here: I am not a screenwriter; I’m just thrilled that the WGA strike was settled. So if you are looking for guidance on how to prep a screenplay entry, I have only one piece of advice for you:

GO ASK SOMEONE WHO DOES IT FOR A LIVING.

Sorry to be so blunt, but I don’t want any of my readers to be laboring under the false impression that this is the place to pick up screenplay formatting tips. Happily, there are both many, many websites out there just packed with expert advice on the subject, and good screenwriting software is easily and cheaply available. I would urge those of you with cinema burning in your secret souls to rush toward both with all possible dispatch.

I can speak with some authority about poetry formatting, however.

Remember how I mentioned yesterday that where contest rules are silent, their organizers generally assume that writers will adhere to standard format — which is to say, the form that folks who publish that kind of writing expect submitters to embrace? Well, that’s true for poetry as well.

So what does standard format for poetry look like? Quite a bit as you’d expect, I’d expect:

* Single-spaced lines within a stanza

* A skipped line between stanzas

* Left-justified text, with a ragged right margin

* Centered title on the first line of the page

* 1″ margins on all sides of the page

* 12-point typeface on white paper, printed on only one side of the page

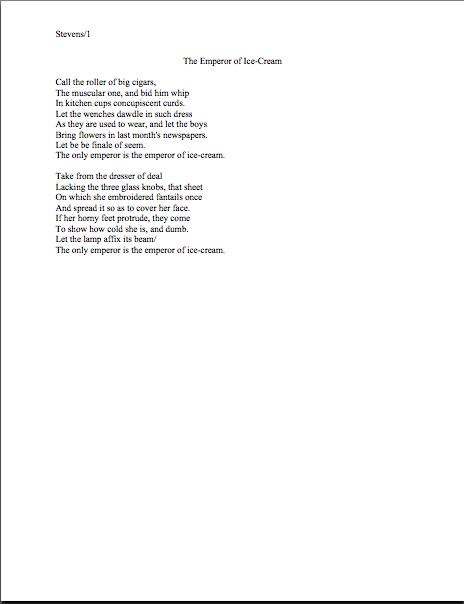

In other words, it shouldn’t be formatted the way you might see it in a book, where the left margin might be a few inches in, or on a greeting card, where the text floats somewhere closer to the center of a page. Basically, the average poetry submission looks like this, to borrow a manuscript page from a favorite poet of mine, Wallace Stevens:

Pretty straightforward, eh? (I love that poem, by the way. I almost named my memoir about my relationship with Philip K. Dick THE EMPEROR OF ICE CREAM. Makes more sense than the title my erstwhile publisher picked, doesn’t it?)

Now let’s see what how a contest rules might call for something slightly different. To pick one set at random, let’s take that nameless contest whose deadline is next week:

* Submit three complete poems.

* Single-space within stanza, double-space between stanzas.

* Maximum length of collection: 3 pgs.

* Use 12pt Times New Roman or Times (Mac).

Those are all of the category-specific rules listed. Elsewhere, however, others pop up, some from rather far afield:

* One-sided 8 1/2 x 11 standard WHITE paper.

* 1” margins all around.

* Have the title of the submission and page numbers located in the upper right hand corner of each page.

* Each submission MUST show the name of the category to which it is submitted.

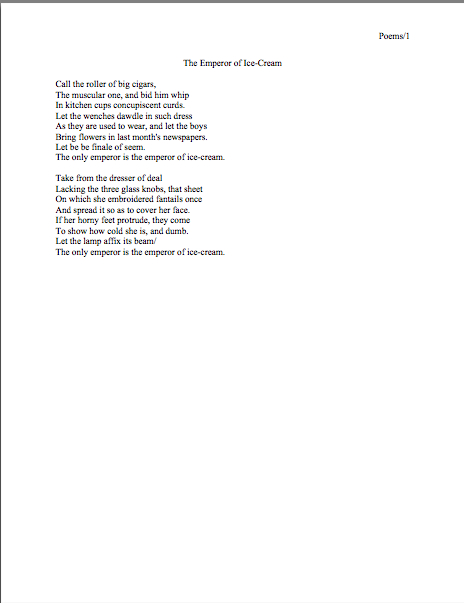

Okay, what can we learn from this? Any occasion for our pal Wallace to panic about the breadth of necessary changes to his already-formatted poem?

Not really. Oh, the rules seem pretty hostile to the notion that any worthwhile poem could possibly be longer than a single page (take that, Lord Byron!), as well as unaware that Word for Mac does in fact feature the Times New Roman font — and has for many years. But otherwise, there’s not a lot here that ol’ Wallace is going to have to change.

EXCEPT, of course, for taking his name out of the slug line and moving it to the other side of the page.

Do I hear some confused muttering out there? “But Anne,” I hear some of you point out, and who could blame you? “What about needing to place the title in the slug line? Each of the three less-than-page-long poems will have a different title, won’t it?”

Great question, unseen mutterers. I’ll complicate it further: in the rules for book-length works, there’s an additional regulation that may apply here:

* The Contest Category name and number (e.g. Category 3: Romance Genre) on the first page of the submission and on the mailing envelope.

Yes, yes, it DOES appear in the section of the rules that apply to categories other than poetry — but tell me, do you want YOUR entry to be the one that tests whether the Contest-That-Shall-Not-Be-Named’s organizers don’t think this rule should apply to the poetry category?

I didn’t think so. If I were a poet, I certainly would not omit scrawling Category 9: Poetry on the outside of my entry envelope.

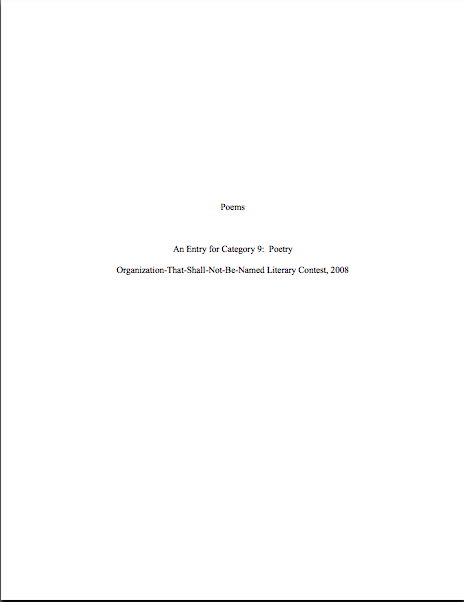

You, of course, are free to do as you wish. But remember how I demonstrated yesterday that adding a title page can help smooth over quite a few little logistical problems? Look what happens to the opening of our pal Wallace’s entry if he takes that advice to heart:

Both of these pages are in Times New Roman, incidentally, created on a Mac. (Hey, I couldn’t resist.)

More to the point, ol’ Wallace has now neatly avoided any rule violations. Oh, he could have given his collection of poetry (if a mere three poems can legitimately be called a collection; if he were a collector of, say, teapots, he would be considered merely a hobbyist collector if he had only three) a more exciting overarching title, but this gets the job done.

It also satisfies the contest’s rule requiring that the title be in the slug line, along with the page number. What’s not to like?

Amazing what a lot of explanation a seemingly simple set of rules can engender, isn’t it? Keep combing through those contest rules, potential entrants, and everybody, keep up the good work!