Still hanging in there, campers? I know, I know: there’s a LOT of information in this basic overview series, but if you start to find it overwhelming, just try to concentrate on the big picture, the broad strokes, rather than feverishly attempting to memorize every detail.

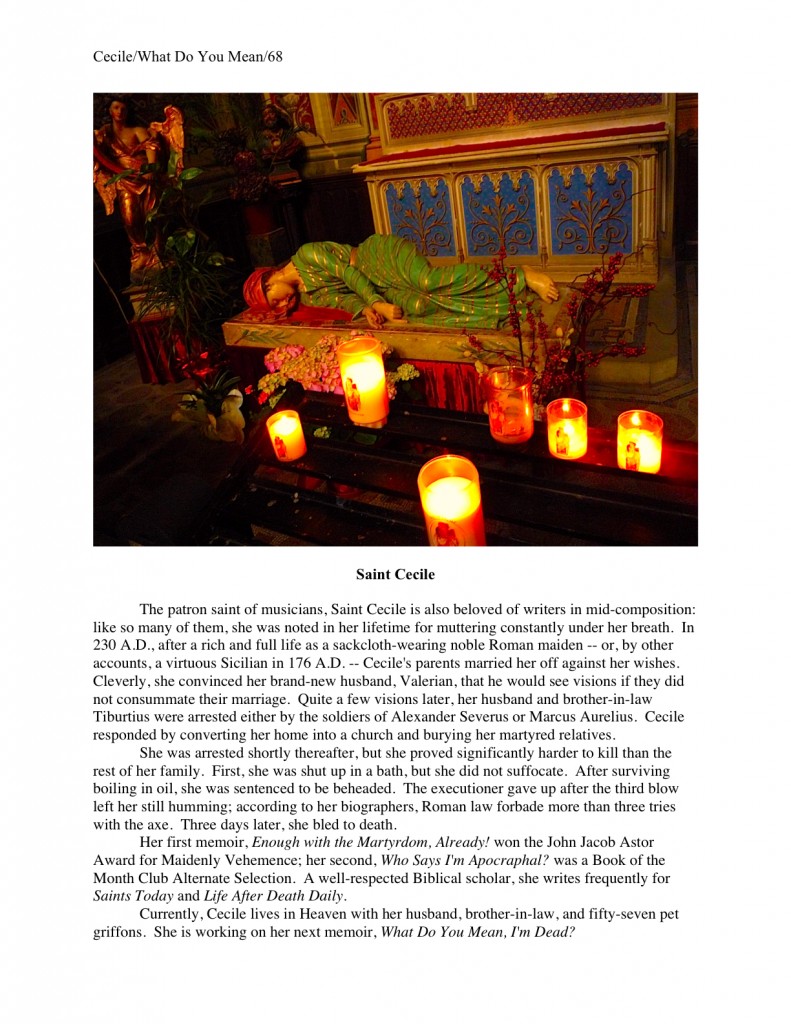

Even if you are not new to the business side of art, it’s good from time to time to distance yourself from the often-trying process of trying to get your writing published. And if you doubt that, do me a favor: rise from your chair, take two steps away from the monitor, and take a gander at the photograph above.

If you don’t see the rock smiling at you, you may be focusing too much on the small picture.

Besides, you can always come back and refresh your memory later. Seriously, it’s easy, if a bit time-consuming. One of the many charms of the blog format lies in its archives: as long as I am running Author! Author!, these posts aren’t going anywhere, and the archives are organized by subject. So please feel free to use this series as a general overview, delving into the more specific posts on individual topics grouped by topic for your perusing convenience on a handy list on the lower right-hand side of this page. There is also a search engine in the upper-right corner, so searchers may type in a word or phrase.

And, as always, if you can’t find the answer to a particular writing question, feel free to ask it in the comments. I’m always on the look-out for new subjects for posts, and readers’ questions are far and away my best source.

Last time, I went over the three basic means of bringing your book to an agent’s attention: querying, either by sending a letter via regular mail (the classic method), approaching by sending an e-mail (the newfangled method) or through the agency’s website (the least controllable), and verbal pitching (far and away the most terrifying. Today, I’m going to talk about the various possibilities of response to your query or pitch.

Which, you may be happy to hear, are relatively limited and very seldom involve anyone being overtly mean. Or calling you and demanding that you give a three-hour dissertation about your book on the spot. Not that these are unreasonable fears, by any means: given how intimidating the querying and pitching processes can be but I find it hard to believe that the possibility of an agent’s being genuinely rude in response hadn’t occurred at least once to all of us before the first time we queried or pitched.

I heard that chortling, experienced pitchers and queriers; I said overtly mean, not dismissive or curt. There’s a big difference. Dismissive and/or curt responses are not personal, usually; overt meanness is.

So to those of you who have never queried or pitched before, I reiterate: the probability that an agent will say something nasty to you about your book at the initial contact stage is quite low. S/he may not say what you want him or her to say — which is, of course, “Yes! I would absolutely love to read the book you’ve just queried/pitched!” — but s/he is not going to yell at you. (At least, not if you’re polite in your approach and s/he is professional.)

At worst, s/he is going to say “No, thank you.”

You can handle that, can’t you? I hope so, because any writer who is in it for the long haul just has to get used to the possibility of hearing no. Because hear it you almost certainly will, no matter how good your manuscript is.

Yes, you read that correctly, newbies: pretty much every writer who has landed an agent within the last decade heard “No, thank you,” many, many times before hearing, “Yes, of course.”

Ditto with virtually every living author who has brought a first book out within the last ten years. At least the ones who were not already celebrities in another field; celebrities have a much easier time attracting representation. (Yes, life is not fair; this is news to you?) That’s just the way the game works these days.

Translation: you should not feel bad if your first query or pitch does not elicit a positive response. Honestly, it would be unusual if it did, in the current market.

Some of your hearts are still racing at the prospect anyway, aren’t they? “Okay, Anne,” a few of you murmur, clutching your chests and monitoring your vital signs, “I understand that it may take a few nos to get to yes. But if an agent isn’t likely either to go into raptures or to fly into an insult-spewing rage after reading a query letter or hearing a pitch, what is likely to happen? I’d like to be prepared for either the best or the worst.”

An excellent plan, oh ye of the racing heart rates. Let’s run through the possibilities.

How can a writer tell whether a query or pitch has been successful?

As we discussed last time, the query letter and pitch share a common goal: not to make the agent stand up and shout, “I don’t need to read this manuscript, by gum! I already know that I want to represent it!” but rather to induce her to ask to see pages of the manuscript. These pages, along with anything else the agent might ask the writer to send (an author bio, for instance, or a synopsis) are known in the trade as requested materials.

So figuring out whether a query or pitch did the trick is actually very simple: if the agent requested materials as a result of it, it was. If not, it wasn’t.

Enjoying this particular brand of success does not mean that a writer has landed an agent, however: it merely means that he’s cleared the first hurdle on the road to representation. First-time pitchers and queriers often get carried away by a provisional yes, assuming that a request for materials means that they will be able to bypass the heart-pumping, nerve-wracking, ego-shredding, and time-consuming process of continuing to query and/or pitch.

And then, a week or a month or three months later, they’re shattered to receive a rejection letter. Or, still worse, they’re biting their nails six months later, waiting to hear back from that first agent who said yes. Shattered hope renders it harder than ever to climb back onto the querying horse.

That’s the bad news. Here’s the good news: writers who walk into the querying and pitching process armed with a knowledge of how it works can avoid this awful fate through a simple, albeit energy-consuming, strategy. Send what that first agent asks to see, but keep querying other agents, just to hedge your bets.

In other words, be pleased with a request for materials, but remember, asking to see your manuscript does not constitute a promise to love it, even if an agent was really, really nice to you during a pitch meeting; it merely means that she is intrigued by your project enough to think that there’s a possibility that she could sell it in the current publishing market.

How can a writer tell whether a query or pitch has been unsuccessful?

If the agent decides not to request materials (also known as passing on the book), the query or pitch has been rejected. If so, the writer is generally informed of the fact by a form letter — or, in the case of e-mailed queries, by a boilerplate expression of regret. Because these sentiments are pre-fabricated and used for every rejection, don’t waste your energy trying to read some deeper interpretation into it; it just means no, thanks. (For more on the subject, please see the FORM-LETTER REJECTIONS category on the archive list.)

Whether the response is positive or negative, it will definitely not be ambiguous: if your query has been successful, an agent will tell you so point-blank. It can be a trifle harder to tell with a verbal pitch, since many agents don’t like watching writers’ faces as they’re rejecting them — which is one reason that a writer is slightly more likely to receive a request for materials from a verbal pitch than a written query, by the way — and will try to let them down gently.

But again, there’s only one true test of whether a pitch or query worked: the agent will ask to see manuscript pages.

Let’s get back to the happy stuff: what if I’m asked to send pages?

If you do receive such a request, congratulations! Feel free to rejoice, but do not fall into either the trap I mentioned above, assuming that the agent has already decided to sign you (he hasn’t, at this stage) or the one of assuming that you must print off the requested pages right away and overnight them to New York (or wherever the agent of your dreams may happen to ply his trade). Both are extremely common, especially amongst pitchers meeting agents for the first time, and both tend to get those new to submission into trouble.

Take a deep breath — and realize that you have a lot of work ahead of you. You will be excited, but that’s precisely the reason that it’s a good idea to take at least a week to pull your requested materials packet together. That will give you enough time to calm down enough to make sure that you include everything the agent asked to see.

How to pull together a submission packet is a topic for another day, however — specifically, the day after tomorrow. Should you find yourself in the enviable position of receiving a request for submissions between now and then, please feel free to avail yourself of the in-depth advice under the HOW TO PUT TOGETHER A SUBMISSION PACKET category on the list at right.

In the meantime, let’s talk about some other possible agently reactions.

What if a writer receives a response other than yes or no?

If you receive a response that says (or implies) that the agency requires writers seeking to be clients to pay for editorial services or evaluation before signing them to contracts, do not say yes before you have done a little homework. In the US, reputable agencies do not charge reading fees — for a good list of what an agent may charge a client, check the Association of Authors’ Representatives website. It’s also an excellent idea to look up an agency that asks for money on Preditors and Editors to see if the agency is legit. You may also post a question about the agency on Absolute Write; chances are, other aspiring writers will have had dealings with the agency. (The last has a lot of great resources for writers new to marketing themselves, by the way.)

Why should you worry about whether an agency is on the up-and-up? Well, every year, a lot of aspiring writers fall prey to scams. Call me zany, but I would prefer that my readers not be amongst the unlucky many.

The main thing to bear in mind in order to avoid getting taken: not everyone who says he’s an agent is one. The fact is, anyone could slap up a website with the word AGENCY emblazoned across the top. Some of the most notorious frauds have some of the most polished and apparently writer-friendly websites.

Scams work because in any given year, there literally millions of English-speaking writers desperate to land an agent and get published, many of whom don’t really understand how reputable agencies work. Scammers prey upon that ignorance — and they can often get away with it, because in the United States, there are no technical qualifications for becoming an agent. Nor is there any required license.

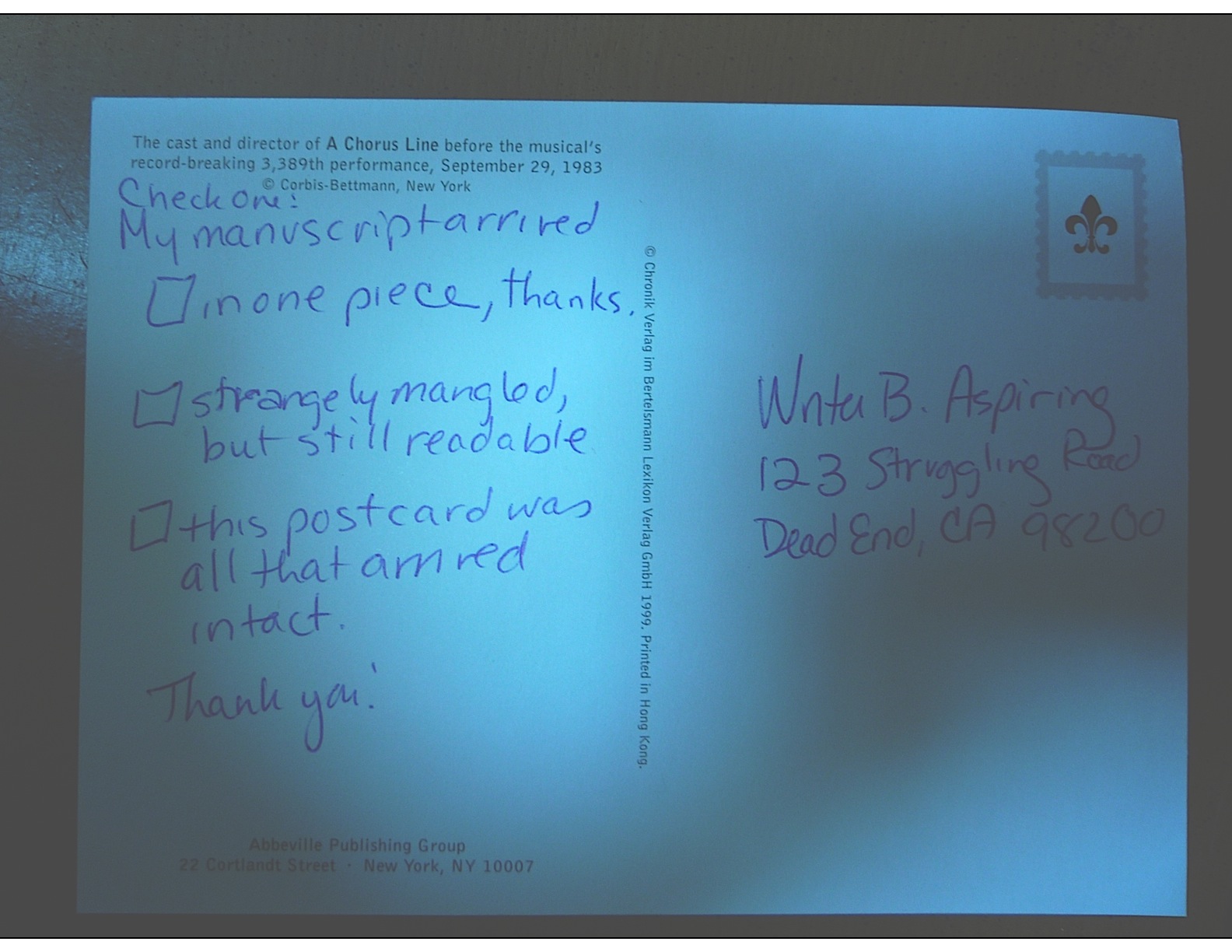

Yes, really: it’s possible just to hang up a shingle and start taking on clients. Or in the case of many scams, start asking potential clients to pay them fees, either directly (as in the notorious We don’t work like other agencies, but we require a paid professional evaluation up front dodge; to see a full correspondence between an actual writer and such a business, check out the FEE-CHARGING AGENCIES category at right) or by referring writers to a specific editing service (i.e., one that gives the agency kickbacks), implying that using this service is a prerequisite to representation.

Reputable agents decide whether to represent a manuscript based upon direct reading; they do not require or expect other businesses to do it for them. Nor do they charge their clients up front for services (although some do charge photocopying fees). A legitimate agency makes its money by taking an agreed-upon percentage of the sales of its clients’ work.

If any so-called agent tries to tell you otherwise, back away, quickly, and consult the Association of Authors’ Representatives or Preditors and Editors immediately. (For a step-by-step explanation of how others have successfully handled this situation, run, don’t walk to the FEE-CHARGING AGENCIES category at right.)

Heck, if you’re not sure if you should pay a requested fee, post a question in the comments here. I would much, much rather you did that than got sucked into a scam.

Better yet, check out any agent or agency before you query. It’s not very hard at all: the standard agency guides (like the Writers Digest GUIDE TO LITERARY AGENTS and the Herman Guide, both excellent and updated yearly) and websites like Preditors and Editors make it their business to separate the reputable from the disreputable.

Fortunately, such scams are not very common. Still, it pays to be on your guard, especially if your primary means of finding agents to query is trolling the internet.

What if a writer receives no response at all?

More common these days is the agency that simply does not respond to a query at all. Agencies that prefer to receive queries online seem more prone to this rather rude practice, I’ve noticed, but over the last few years, an ever-increasing number of queries — and even submissions, amazingly — were greeted with silence.

In many instances, it’s actually become a matter of policy: check the agency’s website or listing in one of the standard agency guides to see if they state it openly. (For tips on how to decipher these sources, please see the HOW TO READ AN AGENCY LISTING category on the list at right.)

A complete lack of response on a query letter does not necessarily equal rejection, incidentally, unless the agency’s website or listing in one of the standard agency guides says so directly. Queries do occasionally get lost, for instance. The single most common reason a writer doesn’t hear back, though, is that the agency hasn’t gotten around to reading it yet.

Be patient — and keep querying other agents while you wait.

Seeing a pattern here?

I certainly hope so. There’s a good reason that I always urge writers to continue querying and pitching after an agent has expressed interest: as I mentioned last time, it can take weeks or even months to hear back about a query, and many agencies now reject queriers through silence. A writer who waits to hear from Agent #1 before querying Agent #2 may waste a great deal of time. Because agents are aware of this, the vast majority simply assume that the writers who approach them are also querying other agents; if they believe otherwise, they will say so on their websites or in their listings in agency guides.

For some guidance on how to expand your querying list so you may keep several queries out at any given time, please see the FINDING AGENTS TO QUERY category on the list at right.

What should a writer do if her query was rejected?

Again, the answer is pretty straightforward: try another agent. Right away, if possible.

What it most emphatically does not mean is that you should give up. Contrary to what virtually every rejected writer believes, rejection does not necessarily mean that the book concept is a poor one; it may just means that the agent doesn’t represent that kind of book, or that she just spent a year attempting to sell a similar book and failed (yes, it happens; landing an agent is no guarantee of publication), or that this book category isn’t selling very well at the moment.

The important thing to bear in mind is that at the query or pitching stage, the book could not possibly have been rejected because the manuscript was poorly written.

The query might have been rejected for that reason, naturally, but it’s logically impossible for an agent to pass judgment on a manuscript’s writing quality without reading it. Makes sense, right?

One piece of industry etiquette to bear in mind: once a writer received a formal rejection letter or e-mail, it’s considered rude to query or pitch that book project to the same agent again. (See why it’s so important to proofread your query?) At some agencies, that prohibition extends to all of the member agents; however, this is not always the case. Regardless, unless a rejecting agent actually tells a writer never to approach him again — again, extremely rare — a writer may always query again with a new book project.

Contrary to an annoyingly pervasive rumor that’s been haunting the conference circuit for decades, being rejected by one agency has absolutely no effect upon the query’s probability of being rejected by another. There is no national database, for instance, that agents check to see who else has seen or rejected a particular manuscript (a rumor I have heard as recently as last week), nor do agencies maintain databases to check whether they have heard from a specific querier before. If you’re going to get caught for re-querying the same agency, it will be because someone at the agency remembers your book project.

You really don’t want to tempt them by sending the same query three months after your last was rejected, though. People who work at agencies tend to have good memories, and an agent who notices that he’s received the same query twice will almost always reject it the second time around, on general principle. In this economy, however, it’s certainly not beyond belief that an agent who feels that he cannot sell a particular book right now may feel quite differently a year or two hence.

I leave the matter of whether to re-query to your conscience, along with the issue of whether it’s kosher to wait a year and send a query letter to an agent who didn’t bother to respond the last time around.

If your query (or manuscript, for that matter) has been rejected, whatever you do, resist the temptation to contact the agent to argue about it, either in writing or by picking up the phone. I can tell you now that it will not convince the agent that his rejection was a mistake; it will merely annoy him, and the last thing your book deserves is for the agent who rejected it to have a great story about an unusually obnoxious writer to tell at cocktail parties.

In answer to what you just thought: yes, they do swap horror stories. Seldom with names attached, but still, you don’t want to be the subject of one. In an industry notorious for labeling even brilliant writers difficult for infractions as innocuous as wanting to talk through a requested major revision before making it, or defending one’s title if the marketing department wants another, or calling one’s agent once too often to see if a manuscript has been sent to an editor, writers new to the game frequently find themselves breaking the unwritten rules.

The no-argument rule is doubly applicable for face-to-face pitching. Trying to get a rejection reversed is just not a fight a writer can win. Move on — because, really, the only thing that will genuinely represent a victory here is your being signed by another agent.

It’s completely natural to feel anger at being rejected, of course, but bickering with or yelling at (yes, I’ve seen it happen) is not the most constructive way to deal with it.

What is, you ask? Sending out another query letter right away. Or four.

Something else that might help you manage your possibly well-justified rage at hearing no: at a good-sized agency — and even many of the small ones — the agent isn’t necessarily the person doing the rejecting. Agencies routinely employ agents-in-training called agency screeners, folks at the very beginning of their careers, to sift through the huge volume of queries they receive every week. Since even a very successful agent can usually afford to take on only a small handful of new clients in any given year, in essence, the screener’s job is to reject as many queries as possible.

Here at Author! Author!, the prototypical agency screener has a name: Millicent. If you stick around this blog for a while, you’re going to get to know her pretty well. And even come to respect her, because, let’s face it, she has a hard job.

Typically, agents give their Millicents a list of criteria that a query must meet in order to be eligible for acceptance, including the single most common reason queries get rejected: pitching a type of book that the agent does not represent. There’s absolutely nothing personal about that rejection; most of the time, it’s just a matter of fit.

What is fit, you ask, and how can you tell if your book and an agent have it? Ah, that’s a subject for tomorrow’s post.

For today, let’s concentrate on the bigger picture. Finding an agent has changed a lot over the last ten or fifteen years; unfortunately, a great deal of the common wisdom about how and why books get picked up or rejected has not. The twin myths that a really good book will instantly find an agent and that any agent will recognize and snap up a really good book are just not true anymore, if indeed they ever were.

I’m not going to lie to you: finding an agent is work; it is often a lengthy process, even for the best of manuscripts. More than ever before, an aspiring writer needs not just talent, but persistence.

I know you have it in you. Keep up the good work!