Ah, another evening, another installment in our gargantuan self-editing series. I have to say, I’ve been having a good time with it — usually, I spend this time of year talking at length about how to construct a winning conference pitch, followed by another couple of weeks devoted to concocting a professional-looking query letter. We’ve been having so much good, productive fun working on revision issues lately, however, that I haven’t wanted to break up the party.

So a summer of craft it is. Onward and upward!

I’m still very much at your service if you are interested in pulling together a pitch, query letter, or synopsis, of course — as always, feel free to ask questions. If you’re in the market for in step-by-step instructions, hie yourself to the quite detailed archive list at the bottom right-hand side of this page, where you will find categories helpfully labeled HOW TO WRITE A PITCH, HOW TO WRITE A REALLY GOOD QUERY LETTER, HOW TO WRITE A REALLY GOOD SYNOPSIS, and HOW TO PUT TOGETHER A QUERY PACKET. After your have pitched or queried successfully, you might want to avail yourself of the posts in the HOW TO FORMAT A BOOK MANUSCRIPT and HOW TO PUT TOGETHER A SUBMISSION PACKET categories.

Or, if you should happen to be perusing these categories in a panic the night before or just after a writers’ conference, searching frantically for the absolute basics, try the HOW TO WRITE A PITCH AT THE LAST MINUTE, HOW TO WRITE A QUERY LETTER IN A HURRY, and HOW TO WRITE A SYNOPSIS IN A HURRY.

In short, please don’t assume that because I’m spending the summer reveling in manuscript problems — because, let’s face it, insofar as anyone can actually revel in manuscript problems, I do — I’m not still interested in helping members of the Author! Author! community with practical marketing. If you don’t find answers to your questions in the archives, please, I implore you, speak up.

Everyone clear on that? Good. Now let’s plunge back into the full enjoyment of revision.

What’s that you say? Enjoy doesn’t precisely capture the emotion current swelling your breast at the prospect of another discussion of manuscript megaproblems? Well, may I at least assume that everyone’s been learning a little something each time?

I sincerely hope that the learning curve has been sharp for many of you, because honestly, I do not think we writers talk amongst ourselves nearly enough about these issues. The art of self-revision is so difficult to teach that many writing gurus eschew it altogether –- and not merely because there is no magical formula dictating, say, how often it’s okay to repeat a word on the page or how many summary statements a chapter can contain before our buddy, Millicent the agency screener, rends her garments and cries, “Enough with the generalizations, already! Show, don’t tell!”

Although experience leads me to believe that the answer is not all that many.

If you take nothing else away from this series, please let it be a firm resolve not to resent Millicent for this response. As we discussed last time, there’s just no getting around the fact that professional readers — i.e., agents, editors, contest judges, agency screeners, editorial assistants, writing teachers — tend to read manuscript pages not individually, like most readers do, but in clumps.

One after another. All the livelong day.

Which, of course, is necessarily going to affect how they read your manuscript — or any other writer’s, for that matter. Think about it: if you saw the same easily-fixable error 25 times a day (or an hour), yet were powerless to prevent the author of submission #26 from making precisely the same rejection-worthy mistake, wouldn’t it make you just a mite testy?

Welcome to Millicent’s world. Help yourself to a latte.

If you’re at all serious about landing an agent, you should want to get a peek into her world, because she’s typically the first line of defense at an agency, the hurdle any submission must clear before a manuscript can get anywhere near the agent who requested it. In that world, the submission that falls prey to the same pitfall as the one before it is far, far more likely to get rejected on page 1 than the submission that makes a more original mistake.

Why, you cry out in horror — or, depending upon how innovative your gaffes happen to be, cry out in relief? Because — feel free to chant along with me now, long-term readers — from a professional reader’s point of view, common writing problems are not merely barriers to reading enjoyment; they are boring as well.

Did the mere thought of your submission’s boring Millicent for so much as a second make you cringe? At this point in our Frankenstein manuscript series, it should.

In not entirely unrelated news, today, I shall be acquainting you with a manuscript problem frequently invisible to the writer who produced it, yet glaringly visible to a professional reader, for precisely the same reason that formatting problems are instantly recognizable to a contest judge: after you’ve see the same phenomenon crop up in 75 of the last 200 manuscripts you’ve read, your eye just gets sensitized to it.

I’m talking, of course, about yet another eminently cut-able category of sentences, statements of the obvious. You know, the kind that draws a conclusion or states a fact that any reader of average intelligence might have been safely relied upon to have figured out for him or herself.

I heard some of you out there chuckle ––you caught me in the act, didn’t you? Yes, the second sentence of the previous paragraph IS an example of what I’m talking about; I was trying to test your editing eye.

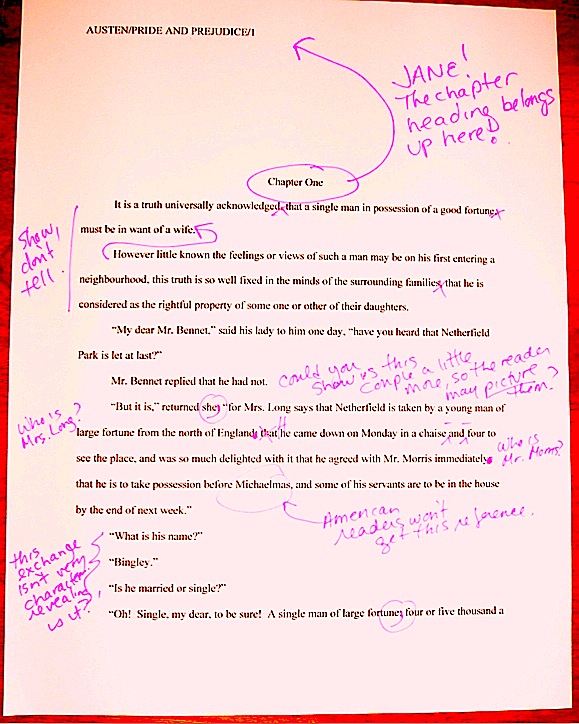

Here I go, testing it again. See how many self-evident statements you can catch in this sterling opening. (Sorry about the slight fuzziness of the page here. As always, if you’re having trouble reading the individual words in the example, try holding down the Command key while hitting +.)

Do correct me if I am wrong, but is not night usually dark? Where else would the moon rise except on the horizon? What else could one possibly shrug other than shoulders — or, indeed, nod with other than a head? Is there a funny bone located somewhere in the body other than the arm, or toes not on the foot?

Seeing a pattern? Are you also seeing abundant invitation for revision, I hope?

Ideally, this sort of statement should send your fingers flying for the DELETE key. Why do I want you to develop a sensitivity to this kind of statement on the page? Well, let me put it this way: any sentence in a submission that prompts Millicent to mutter, “Well, duh!” is a likely rejection-trigger.

Yes, all by itself, even if the rest of the submission is pretty darned clean, perfectly formatted, and well-written to boot. Read on to find out why.

I mention that, obviously, because I fear that some of you might not have understood that in a written argument, discussion of a premise often follows hard upon it, often in the paragraphs just below. Or maybe I just thought that not all of you would recognize the difference between a paragraph break and the end of a blog. I still have a lot to say on the subject.

Rather insulting to the intelligence, isn’t it? That’s how your garden-variety Millicent feels when a sentence in a submission assumes she won’t catch on to something self-evident.

“Jeez,” she murmurs indignantly, “just how dim-witted does this writer think I am? Next!”

Lest that seem like an over-reaction to what in fact was an innocent line of text, allow me to remind you: when you’re reading in order to catch mistakes — as every agency screener, agent, editor, and contest judge is forced to do when faced with mountains of submissions — you’re inclined to get a mite testy. Liability of the trade.

In fact, to maintain the level of focus necessary edit a manuscript really well, it is often desirable to keep oneself in a constant state of irritable reactivity. Keeps the old editing eye sharp.

Those would be the eyes in the head, in case anyone was wondering. Located just south of the eyebrows.

To a professional reader in such a state, the appearance of a self-evident proposition on a page is like the proverbial red flag to a bull: the reaction is often disproportionate to the offense. Even — and I tremble to inform you of this, but it’s true — if the self-evidence infraction is very, very minor.

Don’t believe me? Okay, here is a small sampling of some of the things professional readers have been known to howl at the pages in front of them, regardless of the eardrums belonging to the inhabitants of adjacent cubicles:

In response to the seemingly innocuous line, He shrugged his shoulders: “What else could he possibly have shrugged? His kneecaps?” (Insert violent scratching sounds here, leaving only the words, He shrugged still standing in the text.)

In response to the ostensibly innocent statement, She blinked her eyes: “The last time I checked, eyes are the only part of the body that CAN blink!” (Scratch, scratch, scratch.)

In response to the bland sentence, The queen waved her hand at the crowd: “Waving ASSUMES hand movement! Why is God punishing me like this?” (Scratch, maul, stab pen through paper repeatedly.)

And that’s just how the poor souls react to all of those logically self-evident statements on a sentence level. The assertions of the obvious on a larger scale send them screaming into their therapists’ offices, moaning that all of the writers of the world have leagued together in a conspiracy to bore them to death.

As is so often the case, the world of film provides some gorgeous examples of larger-scale obviousness. Take, for instance, the phenomenon film critic Roger Ebert has dubbed the Seeing-Eye Man: after the crisis in an action film has ended, the male lead embraces the female lead and says, “It’s over,” as though the female might not have noticed something as minor as Godzilla’s disappearance or the cessation of gunfire or the bad guys dead at their feet. In response to this helpful statement, she nods gratefully.

Or the cringing actor who glances at the sky immediately after the best rendition of a thunderclap ever heard on film: “Is there a storm coming?”

Taken one at a time, such statements of the obvious are not necessarily teeth-grinding events – but if they happen too often over the course of the introductory pages of a submission or contest entry, they can be genuine deal-breakers.

Oh, you want to see what that level of Millicent-goading might look like on the submission page, do you? I aim to please. Here’s a little number that I like to call the Walking Across the Room (WATR) problem:

This account is a completely accurate and believable description of the process, right? As narrative in a novel, however, it would also be quite dull for the reader, right because it requires the retailing of so many not-very-interesting events in order to get that door answered. Any reasonably intelligent reader could be trusted to understand that in order to answer the door, she would need to put down the book, rise from the chair, and so forth.

Or, to put it in the terms we’ve been using over the past few days: is there any particular reason that the entire process could not be summed up as She got up and answered the door, so all of the reclaimed page space could be devoted to more interesting activity? Or, if we really wanted to get daring with those editing shears, why not have the narrative simply jump from one state of being to the next, trusting the reader to be able to interpolate the connective logic:

When the ringing became continuous, Jessamyn gave up on peaceful reading. She pushed aside Mom’s to-do list tacked to the front door and peered through the peephole. Funny, there didn’t seem to be anyone there, yet still, the doorbell shrilled. She had only pushed it halfway open when she heard herself scream.

Think Millicent’s going to be scratching her head, wondering how Jessamyn got from the study to the hallway? Or that she will be flummoxed by how our heroine managed to open the door without the text mentioning the turning of the knob?

Of course not. Stick to the interesting stuff.

WATR problems are not, alas, exclusively the province of scenes involving locomotion — many a process has been over-described by dint of including too much procedural information in the narrative. Instead of narrowing down the steps necessary to complete a project to only the most important, or presenting the full array in such a manner that the most vital and interesting steps, a WATR text mentions everything, up to and sometimes including the kitchen sink.

What WATR anxiety — the fear of leaving out a necessary step in a complex process — offers the reader is less a narrative description of a process than a list of every step involved in it, an impression considerably exacerbated by all of those ands. Every detail here is presented as equally important, but the reader is left with no doubt that the account is complete.

WATR problems are particularly likely to occur when writers are describing processes with which they are very familiar, but readers may not be. In this case, the preparation of a peach pie:

As a purely factual account, that’s admirable, right? Should every single pastry cookbook on the face of the earth suddenly be carried off in a whirlwind, you would want this description on hand in order to reconstruct the recipes of yore.

As narrative text in a novel, however, it’s not the most effective storytelling tactic. All of those details, while undoubtedly accurate, swamp the story. Basically, this narrative voice says to the reader, “Look, I’m not sure what’s important here, so I’m going to give you every detail. You get to decide for yourself what’s worth remembering and what’s not.”

Not sure why that’s a serious problem? Be honest now: didn’t your attention begin to wander after just a few sentences? It just goes to show you: even if you get all of the details right, this level of description is not very likely to retain a reader’s interest for long.

Or, as Millicent likes to put it: “Next!”

Do I hear some murmuring from those of you who actually read all the way through the example? “But Anne,” you cry, desperately rubbing your eyes to drive the sleepiness away, “the level of detail was not what bugged me most about that pie-making fiesta. What about all of the ands? What about all of the run-on sentences and word repetition? Wouldn’t those things bother Millicent more?”

I’m glad that you were sharp-eyed enough to notice those problems, eye-rubbers, but honestly, asking whether the repetition is more likely to annoy a professional reader than the sheer stultifying detail is sort of like asking whether Joan of Arc disliked the burning or the suffocating part of her execution more.

Either is going to kill you, right? Mightn’t it then be prudent to avoid both?

In first drafts, the impulse to blurt out all of these details can be caused by a fear of not getting the entire story down on paper fast enough, a common qualm of the chronically-rushed: in her haste to get the whole thing on the page right away, the author just tosses everything she can think of into the pile on the assumption that she can come back later and sort it out. It can also arise from a trust issue, or rather a distrust issue: it’s spurred by the author’s lack of faith in either her own judgment as a determiner of importance, her profound suspicion that the reader is going to be critical of her if she leaves anything out, or both.

Regardless of the root cause, WATR is bad news for the narrative voice. Even if the reader happens to like lists and adore detail, that level of quivering anxiety about making substantive choices resonates in every line, providing distraction from the story. Taken to an extreme, it can even knock the reader out of the story.

Although WATR problems are quite popular in manuscript submissions, they are not the only page-level red flag resulting from a lack of faith in the reader’s ability to fill in the necessary logic. Millicent is frequently treated to descriptions of shifting technique during car-based scenes (“Oh, how I wish this protagonist drove an automatic!” she moans), blow-by-blow accounts of industrial processes (“Wow, half a page on the smelting of iron for steel. Don’t see that every day — wait, I saw a page and a half on the intricacies of salmon canning last week.”), and even detailed narration of computer use (“Gee, this character hit both the space bar and the return key? Stop, my doctor told me to avoid extreme excitement.”)

And that’s not even counting all of the times narratives have meticulously explained to her that gravity made something fall, the sun’s rays produced warmth or burning, or that someone standing in line had to wait until the people standing in front of him were served. Why, the next thing you’ll be telling her is that one has to push a chair back from a table before one can rise from it, descending a staircase requires putting one’s foot on a series of steps in sequence, or getting at the clothes in a closet requires first opening its door.

Trust me, Millicent is already aware of all of these phenomena. You’re better off cutting ALL such statements in your manuscript– and yes, it’s worth an extra read-through to search out every last one.

That’s a prudent move, incidentally, even if you are absolutely positive hat your manuscript does not fall into this trap very often. Remember, you have no control over whose submission a screener will read immediately prior to yours. Even if your submission contains only one self-evident proposition over the course of the first 50 pages, if it appears on page 2 and Millicent has just finished wrestling with a manuscript where the obvious is pointed out four times a page, how likely do you think it is that she will kindly overlook your single instance amongst the multifarious wonders of your pages?

You’re already picturing her astonishing passersby with her wrathful comments, aren’t you? Excellent; you’re getting the hang of just how closely professional readers read.

The trouble is, they’re hard to catch. Self-evident statements virtually always appear to the writer to be simple explanation. Innocuous, or even necessary. “What do you mean?” the writer of the obvious protests indignantly. “Who could possibly object to being told that a character lifted his beer glass before drinking from it? How else is he going to drink from it?”

How else, indeed?

Provide too much information about a common experience or everyday object, and the line between the practical conveyance of data and explaining the self-evident can become dangerously thin. I’ve been using only very bald examples so far, but let’s take a look at how subtle self-evidence might appear in a text:

The hand of the round clock on the wall clicked loudly with each passing second, marking passing time as it moved. Jake ate his cobbler with a fork, alternating bites of overly-sweetened ollallieberry with swigs of coffee from his mug. As he ate, farmers came into the diner to eat lunch, exhausted from riding the plows that tore up the earth in neat rows for the reception of eventual seedlings. The waitress gave bills to each of them when they had finished eating, but still, Jake’s wait went on and on.

Now, to an ordinary reader, rather than a detail-oriented professional one, there isn’t much wrong with this paragraph, is there? It conveys a rather nice sense of place and mood, in fact. But see how much of it could be trimmed simply by removing embroideries upon the obvious:

The round clock on the wall clicked loudly with each passing second. Jake alternated bites of overly-sweetened ollallieberry cobbler with swigs of coffee. As he ate, farmers came into the diner, exhausted from tearing the earth into neat rows for the reception of eventual seedlings. Even after they had finished eating and left, Jake’s wait went on and on.

The reduction of an 91-word paragraph to an equally effective 59-word one may not seem like a major achievement, but in a manuscript that’s running long, every cut counts. The shorter version will make the Millicents of the world, if not happy, at least pleased to see a submission that assumes that she is intelligent enough to know that, generally speaking, people consume cobbler with the assistance of cutlery and drink fluids from receptacles.

Who knew?

Heck, a brave self-editor might even go out on a limb and trust Millicent to know the purpose of plowing and to understand the concept of an ongoing action, trimming the paragraph even further:

The round clock on the wall clicked loudly with each passing second. Jake alternated bites of overly-sweetened ollallieberry cobbler with swigs of coffee. Farmers came into the diner, exhausted from tearing the earth into neat rows. Even after they had left, Jake’s wait went on and on.

That’s a cool 47 words. Miss any of the ones I excised, other than perhaps that nice bit about the seedlings?

Fair warning: self-evidence is one of those areas where it honestly is far easier for a reader other than the writer to catch the problem, though, so if you can line up other eyes to scan your submission before it ends up on our friend Millicent’s desk, it’s in your interest to do so.

In fact, given how much obviousness tends to bug Millicent, it will behoove you to make a point of asking your first readers to look specifically for instances of self-evidence. Hand ‘em the biggest, thickest marking pen in your drawer, and ask ‘em to make a great big X in the margin every time the narrative takes the time to explain that rain is wet, of all things, that a character’s watch was strapped to his wrist, of all places, or that another character applied lipstick to — wait for it — her lips.

I am now going to post this blog on my website on my laptop computer, which is sitting on a lap desk on top of — you’ll never see this coming — my lap. To do so, I might conceivably press buttons on my keyboard or even use my mouse for scrolling. If the room is too dark, I might switch the switch on my lamp to turn it on. After I am done, I might elect to reverse the process to turn it off.

You never can tell; I’m wacky that way. Keep up the good work!

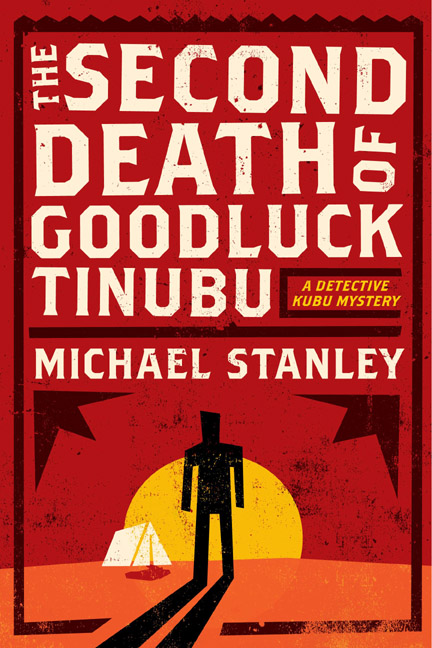

Paul Reynolds, a photographer who creates fake photos for tabloid magazines, wakes up with no idea where he is or how he got there. He can’t even recall his name. A strange man lurks nearby, breathing heavily and slowly flipping through a book. Paul hears the man’s breath, but he cannot see him. He realizes with mounting panic that his eyes no longer function.

Paul Reynolds, a photographer who creates fake photos for tabloid magazines, wakes up with no idea where he is or how he got there. He can’t even recall his name. A strange man lurks nearby, breathing heavily and slowly flipping through a book. Paul hears the man’s breath, but he cannot see him. He realizes with mounting panic that his eyes no longer function.

Those of you who were hanging around the Author! Author! virtual lounge may remember Stan from last year, when he was kind enough to visit with

Those of you who were hanging around the Author! Author! virtual lounge may remember Stan from last year, when he was kind enough to visit with  How can a man die twice?

How can a man die twice?

Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip.

Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip.