Are you still hanging in there after 6 pm’s packed-to-the-gills post, campers? Good for you. In deference to anyone who might happen to be sleeping next to someone reading this, I’m going to keep it down in this, the third post in our Querypalooza series (which began at 10 am yesterday morning, for those of you just tuning in; I shall be posting every 8 hours or so throughout Labor Day weekend.)

So get comfortable, and we’ll warm up to the hardcore discussion of query letters in a casual manner, with a nice, calming, verdure-based anecdote about interpersonal vitriol.

Until a couple of months ago, we lived next door to people who simply couldn’t abide trees, or indeed, greenery in any form. I’m not talking about a minor antipathy to swaying cedars, either — the mere sight of any leaf-bearing living thing irritated the adults in this family into a frenzy of resentment.

Particularly if the leaf in question happened to detach itself from its parent plant and respond to gravity. Not so much as a stray blade of grass ever seemed to evade their notice: their yard could not have had more impervious surfaces if it were an industrial kitchen.

At least twice a year, the Smiths (not their real name, but a clever pseudonym designed to hide their true identities) would demand that we chop down our magnificent willow tree. The rest of the time, they contented themselves with scowling at our ornamental crabapple, refusing gifts of homegrown pears, and swearing audibly throughout the entirety of their every-other-day concrete-sweeping extravaganzas. That last ritual began just after they very pointedly ripped out their (uncovered, with five children in residence) swimming pool because, they told us huffily, OTHER PEOPLE’S leaves kept blowing into it.

Just between us, we like trees on our side of the fence. So did the people who owned the house before us, and so do all of our neighbors except the dreaded Smiths. We live in Seattle, for heaven’s sake, where a proposal to rip out a single 100-year-old cedar on private property typically attracts fifty citizens to a public meeting to howl in protest. In fact, prior to a recent city council election, I received more than one circular explaining where all the candidates stood on trees (sometimes literally, judging by the photographs) and their possible removal.

If I were a tree forced to live in an urban environment, in short, I’d definitely move here.

So in the Smith’s view, we were far from their only inconsiderate neighbors — we are merely the geographically closest in a municipality gone greenery-mad. We were, however, the only locals who kept bringing them holiday cookies in the hope of smoothing things over, as well as the only ones to tell them to go ahead and cut off branches at the property line, as is their right.

This neighborly behavior did not win us any Brownie points with the Smiths, alas, and with good reason: long after the cookies disappeared down their gullets, our willow tree still greeted them every morning by waving its abundant leaves at them. I don’t know if you’ve ever lived in close proximity to one of these gracefully-swaying giants, but they have two habits that drive people like the Smiths nuts: they love dropping leaves that are, unfortunately, susceptible to both gravity and wind, and they just adore snaking their branches into places where there aren’t other trees.

Like, say, the parking lot that was the Smiths’ yard.

Thus, I cannot truthfully say I was surprised to walk into our yard to discover Mr. Smith ten feet up in the willow, hacksaw in hand and murder in his eye. (I talked him down before any branches fell.) Nor was I stunned when the Smiths tore down the fence between our yards, propping the old fence on our lilac and laurel for a few weeks, apparently in the hope that the trees wouldn’t like it much. (They didn’t, but they survived.) Or when the two trees closest to the new fence shriveled up and died (dropping MASSES of leaves in the process, mostly on the Smith’s concrete) because someone had apparently dumped a bunch of weed killer on them.

The arborist said he sees that a lot.

In the interest of maintaining good relationships on the block, we let all it all go, apart from telling Mr. Smith that our insurance wouldn’t cover neighbors plummeting from our tree and laughing as though his repeated requests that we remove the willow taller than our house were a tremendously funny joke that just keeps getting more humorous with each telling. We just stopped plant anything close to the fence and heroically resisted the urge to shake our trees just before one of the Smiths’ immensely noisy yard parties.

From the Smiths’ point of view, of course, this response was unsatisfactory in the extreme: from their perspective, we held all the power, as we were the stewards of the tallest trees in the neighborhood. (Which shade a stream that runs off to a salmon breeding ground; we are the ones who explain to new neighbors not to use anything toxic on their yards, lest it run into the stream.) We were the harborers of raccoons, the protectors of the possums, the defenders of that unsightly hawks’ next.

To them, we had a monopoly on the ability to change the situation, and that, to put it mildly, irks them so much that each spring, I trembled for the baby hawks.

Seen from our side of the fence, though, the Smiths possessed a far from insignificant power: the ability to annoy us by molesting wildlife, intimidating our cat, and poisoning our trees. We quietly took defensive steps, trying to avoid open confrontation, but we could not always protect ourselves or our furry friends. (Because I love you people, I’ll spare you the story of what happened when someone in the neighborhood fed the mother of three small raccoon cubs wet cat foot with broken glass mixed into it.)

So we, the Smiths, the wildlife, and the rest of the neighborhood lived in a state of uneasy détente, at least until the day we were moving the debris from the dead trees. Even though our efforts were speeded by audible cheering from the Smiths’ house, I could have sworn that we had cleared the ground. Yet a couple of days later, branches littered our side of the fence again. We carted those away, only to discover the following week piles of leaves that had apparently fallen from trees that were no longer there.

The Smiths had evidently decided to start dumping fallen leaves over the fence. That showed us, didn’t it?

Why am I sharing this lengthy tale of woe and uproar, other than to demonstrate my confidence that no one on the Smiths’ side of the fence reads? Because our situation with the neighbors so closely paralleled the relationship between agents and many of the aspiring writers who query them.

Yes, really: by everyone’s admission, the agents own the trees — but that doesn’t mean that aspiring writers don’t resent clearing up the leaves. Or that they don’t in their own small ways have the ability to annoy agents quite a bit.

I sense some of you settling in to enjoy my account of this. “Pop some popcorn, Martha,” long-time query-resenters cry. “We’re going to have us some entertainment!”

Don’t get your hopes up — most of these annoyance tactics are only visible from the agents’ side of the fence. Completely generic Dear Agent letters, for instance. Sneaking a few extra lines above the prescribed page into an e-mailed query letter because, after all, what agency screener is going to have time to check that whether it ran longer? Shrinking the margins and/or the typeface on a paper query so that while it is technically a single page, it contains a page and a half’s worth of words. Deciding that the agency website didn’t really mean it about sending only the first five pages with the query, since something really great happens on page 6 of yours. Continuing to e-mail after a rejection, trying to plead the book’s case. Telephoning at all, ever.

Oh, and all of those nit-picky little manuscript problems we have been discussing all summer. Including any or all of those can be a trifle annoying, too.

Think about that, I implore you, the next time you are tempted to bend an agency or contest’s submission rules. While dumping the leaves over the fence might well make the Smiths feel better, it certainly didn’t render them any more likely to convince us to rip out all of our trees; if anything, it’s made us more protective of them.

By the same token, aspiring writers’ attempts to force agents to change the way they do business by ignoring stated guidelines and industry-wide expectations doesn’t achieve the desired effect, either. It merely prompts agencies to adopt more and more draconian means of weeding out submissions.

Nobody wins, in short.

While you’re thoughtfully crunching popcorn and turning that little parable over in your mind, I’m going to switch sides and talk about that great annoyer of the fine folks on the other side of the querying-and-submission fence, querying fatigue.

Those of you who have been seeking agents for a while are familiar with the phenomenon, right? It’s that dragging, soul-sucking feeling that every querier — and submitter, and contest entrant — feels if and when that SASE comes back stuffed with a rejection. “Oh, God,” every writer thinks in that moment, “I have to do this again?”

Unfortunately, if an aspiring writer wants to land an agent, get a book published by press large or small instead of self-publishing, or win a literary contest, s/he DOES need to pick that ego off the ground and keep moving forward.

Stop glaring at me — that’s just a fact.

Yes, querying is a tough row to hoe, both technically and psychologically. But here’s a comforting thought to bear in mind: someone who reads only your query, or even your query and synopsis, cannot logically be rejecting your BOOK, or even your writing.

Why did that make some of you gasp? Logically speaking, to pass a legitimate opinion on either, she would have to read some of your manuscript.

I’m quite serious about this — aspiring writers too often beat themselves up unduly over query rejections, and it just doesn’t make sense. Unless the agency you are querying is one of the increasingly common ones that asks querants to include a brief writing sample, what is rejected in a query letter is either the letter itself (for unprofessionalism, lack of clarity, or simply not being a kind of book that particular agent represents), the premise of the book, or the book category.

Those are the only possibilities, if all you sent was a query. So, if you think about it, there is NO WAY that even a stack of rejection letters reaching to the moon could be a rejection of your talents as a writer, provided those rejections came entirely from cold querying.

Makes you feel just the tiniest bit better to think of rejections that way, doesn’t it?

“But Anne,” some of you protest through a mouthful of popcorn, “I make a special point of querying only agencies whose websites ask me to imbed a few pages in my e-query or on its submission form. So when those folks reject me — or more commonly these days, just don’t respond — I should take that as a rejection of my writing talent and/or book, right, and not just of my query?”

Not necessarily. You have no way of knowing whether the rejection happened before Millicent finished reading the query (the most frequent choice), after she finished reading it, on page 1 of the writing sample, or at the end of it. All you know for sure is that something in your query packet triggered rejection.

The query is the most sensible first choice for reexamination, since it’s the part of the query packet that any Millicent would read first — or at all. After all, if the query itself didn’t grab her attention (or if it dumped any of those pesky leaves over her fence), it’s unlikely to the point of laughability that she read the attached pages.

In response to all of those jaws I just heard hitting the floor, allow me to repeat that: typically, professional readers stop reading the instant they hit a red flag. True of Millicents, true of contest judges, even frequently true of editors. Sorry to be the one to break that to you.

The vast majority of queriers and pitchers do not understand this. They think, and not without some justification, that if an agent’s website asks for ten pages of text, that someone at the agency is going to be standing over Millicent with a whip and a chair, forcing her to read that last syllable on p. 10 before making up her mind whether to reject the query.

Just doesn’t happen. Nor would it be fair to our Millie if it did. In practice, she simply does not have the time to scan every syllable.

Even at a mere 30 seconds per query — far less than writers would like, but still, about average — screening 800-1200 queries per week would equal one full work day each week doing absolutely nothing else…like, say, reading all of those submissions from aspiring writers whose pages she actually requested.

Besides, from her point of view, why should she take the time to read the entirety of a query letter whose first paragraph or two is covered with those annoying leaves? “Someone ought to take a rake to this letter,” she grumbles, slurping down her latte. “Next!”

A pop quiz, to see if you’ve been paying attention: is the best strategic response to this kind of rejection to

(a) decide that the rejection constitutes the entire publishing world’s condemnation of the entire book and/or your talent as a writer, and never query again?

(b) conclude that the manuscript itself was at fault, and frantically revise it for a year before querying again?

(c) e-mail the agency repeatedly, pointing out all of your manuscript’s finer points in an effort to get them to change their minds about rejecting your query?

(d) insist that Millicent was a fool and send out exactly the same query packet to the next agency?

(e) scrutinize both the query and the pages for possible red flags, then send out fresh queries as soon as possible thereafter?

If you said (a), you’re like half the unpublished writers in North America: not bad company, but also engaging in behavior that renders getting picked up by an agent (or winning a contest, for that matter) utterly impossible. I’ve said it before, and I’ll doubtless say it again: even a thoughtful rejection is only one reader’s opinion; no single rejection of a query or submission could possibly equal the condemnation of the entire publishing industry.

If you said (b), you’re like many, many conscientious aspiring writers: willing, even eager to believe that your writing must be faulty; if not, any agency in the world would have snapped it up, right? (See the previous paragraph on the probability of a single Millicent’s reaction being an infallible indicator of that.)

If you said (c), I hope you find throwing those leaves over the fence satisfying. Just be aware that it’s not going to convince Millicent or her boss to chop down the willow.

If you said (d), well, at least you have no illusions that need to be shattered. You are tenacious and believe in your work. Best of luck to you — but after the tenth or fifteenth rejection, you might want to consider the possibility that there are a few leaves marring the beauty of your query letter or opening pages.

If you said (e), congratulations: you have found a healthy balance between pride and practicality. Keep pushing forward.

While we’re considering the possibility of fallen leaves, let me bring up the most common fallen leaf of all: boasting about the writing quality, originality of the book concept, or future literary importance of the writer in the query. If your query contains even a hint of this, take it out immediately.

Why, you ask? Agents and editors tend to be wary of aspiring writers who praise their own work, and rightly so. To use a rather crude analogy, boasts in queries come across like a drunk’s insistence that he can beat up everybody else in the bar, or (to get even cruder) like a personal ad whose author claims that he’s a wizard in bed.

He’s MAKING the bed, naturally, children. Go clean up your respective rooms.

My point is, if the guy were really all that great at either, wouldn’t other people be singing his praises? Isn’t the proof of the pudding, as they say, in the eating?

Even if you are feeling fairly confident that your query does not stray into the realm of self-review, you might want to ask someone whose reading eye you trust to take a gander at your query, to double-check that you’ve removed every last scintilla. Why? Well, aspiring writers are not always aware that they’ve crossed the line from confident presentation to boasting.

To be fair, the line can be a mite blurry. As thoughtful reader Jake asked some time back, in the midst of one of my rhapsodies on pitching:

I’ve been applying this series to query writing, and I think I’ve written a pretty good elevator speech to use as a second paragraph, but there’s something that bothers me.

We’ve been told countless times not to write teasers or book-jacket blurbs when trying to pick up an agent. (”Those damned writer tricks,” I think was the term that was used)

I’m wondering exactly where the line between blurbs and elevator speeches are, and how can I know when I’ve crossed it. Any tips there?

Jake, this is a great question, one that I wish more queriers would ask themselves. The short answer:

A good elevator speech/descriptive paragraph in a query letter describes the content of a book in a clear, concise manner, relying upon intriguing specifics to entice a professional reader into wanting to see actual pages of the book in question.

whereas

A back jacket blurb is a micro-review of a book, commenting upon its strengths, usually in general terms. Usually, these are written by someone other than the author, as with the blurbs that appear on book jackets.

The former is a (brief, admittedly) sample of the author’s storytelling skill; the latter is promotional copy. To translate that into the terms of this post, the first’s appearance in a query letter is professional, while the second is a shovelful of fallen leaves.

Many, if not most, queriers make the mistake of regarding query letters — and surprisingly often synopses, especially those submitted for contest entry, as well — as occasions for the good old American hard sell, boasting when they should instead be demonstrating. Or, to put it in more writerly language, telling how great the book in question is rather than showing it.

From Millicent’s perspective — as well as her Aunt Mehitabel’s when she is judging a contest entry — the difference is indeed glaring. So how, as Jake so asks insightfully, is a querier to know when he’s crossed the line between them?

As agents like to say, it all depends on the writing, and as my long-term readers are already aware, I’m no fan of hard-and-fast rules. However, here are a couple of simple follow-up questions to ask while considering the issue:

(1) Does my descriptive paragraph actually describe what the book is about, or does it pass a value judgment on it?

Remember, if Millicent can’t tell her boss what your book is about, she’s going to have a hard time recommending that the agency pick it up. So go ahead and tell her; resist the temptation to use your dream back-jacket blurb.

The typical back-jacket blurb isn’t intended to describe the book’s content — it’s to praise it, in the hope of attracting readers. And as counter-intuitive as most queriers seem to find it, the goal of a query letter is not to praise the book, but to pique interest in it.

See the difference? Millicent does. So do her Aunt Mehitabel and her cousin Maury, who screens manuscripts for an editor at a major publishing house.

(2) Does my query present the book as a reviewer might, in terms of the reader’s potential enjoyment, assessment of writing quality, speculation about sales potential, and assertions that it might make a good movie? Or does my query talk about the book in the terms an agent might actually use to try to sell it to an editor at a publishing house?

I’ve said it before, and I’ll no doubt say it again: an effective query describes a book in the vocabulary of the publishing industry, not in terms of general praise. (If you’re not certain how to do that, don’t worry — we’ll be getting to that later this weekend.)

(3) Are the sentences that strike me as possibly blurb-like actually necessary to the query letter, or are they extraneous?

I hate to be the one to break it to you, but the average query letter is crammed to the gills with unnecessary verbiage. Just as your garden-variety unprepared pitcher tends to ramble on about how difficult it has been to find an agent for her book, what subplots it contains, and what inspired her to write the darned thing in the first place, queriers often veer off-track to discuss everything from their hopes and dreams about how well the book could sell (hence our old friend, “It’s a natural for Oprah!”) to mentioning what their kith, kin, and writing teachers thought of it (“They say it’s a natural for Oprah!”) to thoughtfully listing all of the reasons that the agent being queried SHOULDN’T pick it up (“You probably won’t be interested, because this isn’t the kind of book that ends up on Oprah.”)

To Millicent and her fellow screeners, none of these observations are relevant. You don’t have very much space in a query letter; use it to provide only the information that’s required.

(4) Does my query make all of the points I need it to make?

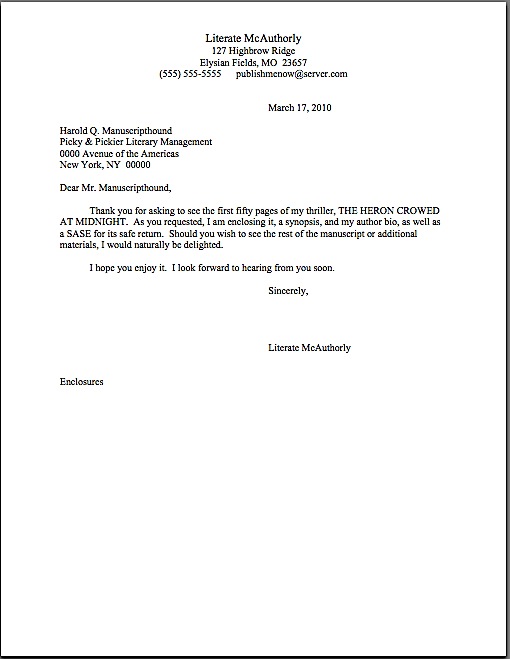

Oh, you may laugh, but humor me for a moment while we go over the basics. A successful query letter has at minimum ALL of the following traits:

* it is clear,

* it is less than 1 page (single-spaced),

* it describes the book’s premise (not the entire book; that’s the job of the synopsis) in an engaging manner,

* it is politely worded,

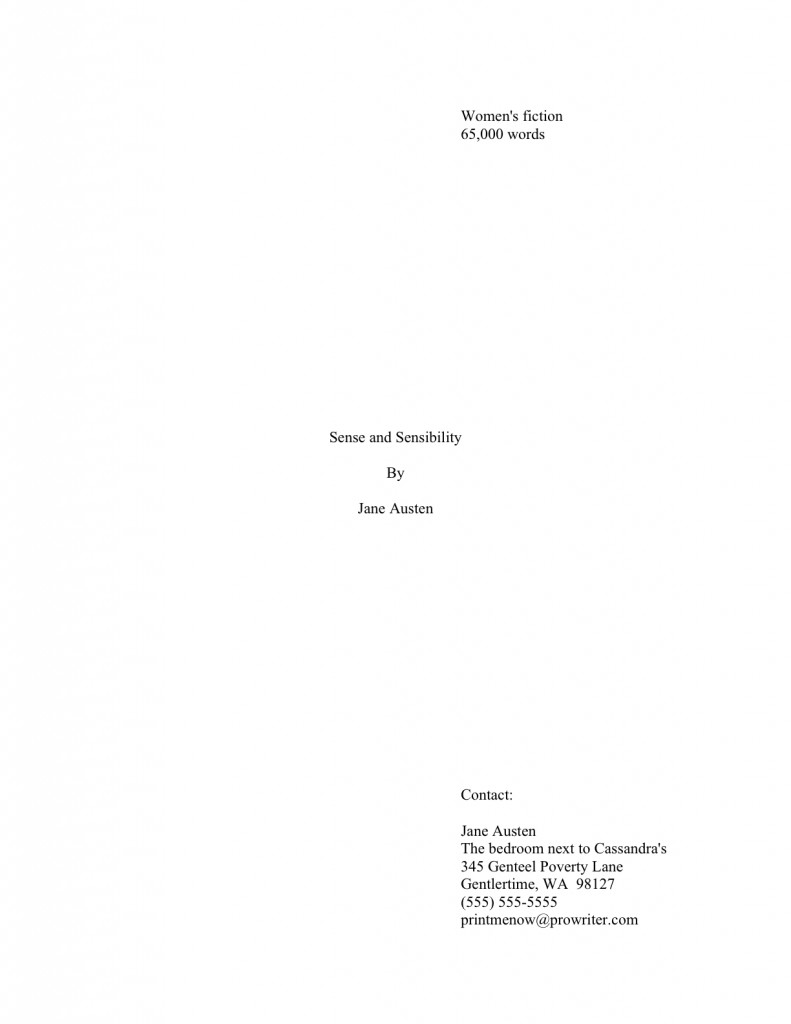

* it states unequivocally what kind of book is being pitched, using a book category that already exists in the publishing industry, rather than one the writer has simply made up,

* it mentions whether the book in question is fiction or nonfiction,

* if it is nonfiction, it includes some description of the writer’s platform (credentials for writing the book, including expertise and/or celebrity status),

* it includes a SASE (if it is being sent via regular mail) or full contact information for the querier, and

* it is addressed to a specific agent with a successful track record in representing the type of book it describes.

You would not believe how few query letters that agencies receive actually have all of these traits. (Yes, even the fiction/nonfiction bit is often omitted.) And to be brutally blunt about it, agents rather like that, because, as I mentioned in my last, it makes it oh-so-easy to reject 85% of what they receive within seconds.

No fuss, no muss, no reading beyond, say, line 5. Again, sound familiar?

A particularly common omission: the book category. Many writers just don’t know that the industry runs on book categories, not vague descriptions. That’s unfortunate, because it would be literally impossible for an agent to sell a book to a publisher without a category label.

Other writers, bless their warm, fuzzy, and devious hearts, think that they are being clever by omitting it, lest their work be rejected on category grounds. “This agency doesn’t represent mysteries,” this type of strategizer thinks, “so I just won’t tell them what kind of book I’ve written until after they’ve fallen in love with my writing.”

I have a shocking bit of news for you, Napolèon: publishing simply doesn’t work that way; if they do not know where it will eventually rest on a shelf in Barnes & Noble, they’re not going to read it at all.

Yes, for most books, particularly novels, there can be legitimate debate about which shelf would most happily house it, and agents recategorize their clients’ work all the time (it’s happened to me, and recently). However, people in the industry speak and even think of books by category.

Trust me, you’re not going to win any Brownie points with them by making them guess what kind of book you’re trying to get them to read.

If you don’t know how to figure out your book’s category, or why you shouldn’t just make one up, please, I implore you, click on the HOW TO FIGURE OUT YOUR BOOK’S category on the archive list at right before you send out your next query letter. Or pitch. Or, really, before you or anything you’ve written comes within ten feet of anyone even vaguely affiliated with the publishing industry.

But I’m veering off into specifics, amn’t I? We were talking about general principles.

(5) Does my query make my book sound appealing — not just to any agent, but to the kind of agent who would be the best fit for my writing?

You wouldn’t believe how many blank stares I get when I ask this one in my classes, but as I’ve pointed out before, you don’t want just any agent to represent your work; you want one with the right connections to sell it to an editor, right?

That’s not a match-up that’s likely to occur through blind dating, if you catch my drift. You need to look for someone who shares your interests.

I find that it often helps aspiring writers to think of their query letters as personal ads for their books. (Don’t pretend you’re unfamiliar with the style: everyone reads them from time to time, if only to see what the new kink du jour is.) In it, you are introducing your book to someone with whom you are hoping it will have a long-term relationship – which, ideally, it will be; I have relatives with whom I have less frequent and less cordial contact than with my agent – and as such, you are trying to make a good impression.

So which do you think is more likely to draw a total stranger to you, ambiguity or specificity in how you describe yourself?

To put it another way, are you using the blurb or demonstration style? Do you, as so many personal ads and queries do, describe yourself in only the vaguest terms, hoping that Mr. or Ms. Right will read your mind correctly and pick yours out of the crowd of ads? Or do you figure out precisely what it is you want from a potential partner, as well as what you have to give in return, and spell it out?

To the eye of an agent or screener who sees hundreds of these appeals per week, writers who do not specify book categories are like personal ad placers who forget to list minor points like their genders or sexual orientation. It really is that basic, in their world.

And writers who hedge their bets by describing their books in hybrid terms, as in it’s a cross between a political thriller and a gentle romance, with helpful gardening tips thrown in, are to professional eyes the equivalent of personal ad placers so insecure about their own appeal that they say they are into long walks on the beach, javelin throwing, or whatever.

Trust me, to the eyes of the industry, this kind of complexity doesn’t make you look interesting, or your book a genre-crosser. To them, it looks at best like an attempt to curry favor by indicating that the writer in question is willing to manhandle his book in order to make it anything the agent wants.

At worst, it comes across as the writer’s being so solipsistic that he assumes that it’s the query-reader’s job to guess what whatever means in this context. And we all know by now how agents feel about writers who waste their time, don’t we?

Don’t make ‘em guess; be specific, and describe your work in the language they understand. Because otherwise, they’re just not going to understand the book you are offering well enough to know that any agent in her right mind — at least, anyone who has a substantial and successful track record in selling your category of book — should ask to read all or part of it with all possible dispatch.

I know you’re up to this challenge; I can feel it. Don’t worry, though — you don’t need to pull it off within the next thirty seconds, regardless of what that rush of adrenaline just told you.

But don’t, whatever you do, vent your completely understandable frustration in self-defeating leaf-dumping. It’s a waste of energy, and it will not get you what you want.

More discussion of the ins and outs of querying follows at 10 am, naturally. Sweet dreams, campers, and keep up the good work!