That’s an actual stone in my yard, believe it or not, one that apparently went out of its way to anthropomorphize itself for my illustrative pleasure. If rocks can be that friendly and helpful, it gives me great hope for human beings.

Which is my subtle way of leading into asking: after these last few weeks of posts, have you start to have dreams about pitching? If they’re not nightmares, and you’re scheduled to pitch at a conference anytime soon, you’re either a paragon of mental health, a born salesperson, or simply haven’t been paying very close attention. Either that, or I’ve seriously underemphasized the potential pitfalls.

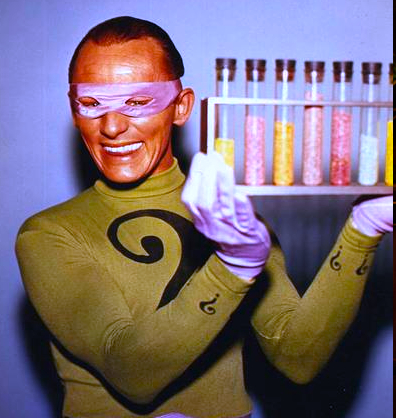

For the next couple of days, I’m going to assume that you either ARE waking up in the night screaming or that I haven’t yet explained this adequately. So fasten your seatbelts — I’m going to be taking you on a guided tour of false expectations, avoidable missteps, and just plain disasters.

Hey, forewarned is forearmed. Or at least less surprised.

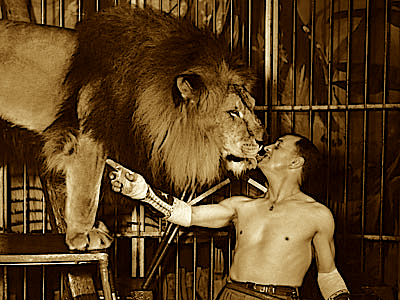

One of the fears first-time pitchers often harbor is inadvertently making a poor impression upon an agent or editor, thereby nullifying their chances of being able to wow ‘em with a pitch. I wish I could say that this is an unfounded fear, but actually, it’s pretty reasonable: one doesn’t have to spend much time hanging around that bar that’s never more than 100 yards from any writers’ conference in North America to hear a few horror stories about jaw-droppingly rude writers.

Before anybody out there begins to panic, let me hasten to add that jaw-droppingly is the operative term here. These anecdotes are almost invariably about genuinely outrageous approach attempts — and not just because “You’re not going to believe this, but a pitcher just forgot to tell me whether is book is fiction or nonfiction” isn’t nearly as likely to garner sympathy from fellow bar denizens as “This insane writer just grabbed my arm as I was rushing into the bathroom and refused to stop talking for 20 minutes.”

For one thing, the former is too common a phenomenon to excite much of a response from other agents. Unfortunately, though, the latter happens often enough that some agents turn against hallway pitching for life.

However — and this is a BIG however — the aspiring writers who sit around and fret about being the objects of such anecdotes are virtually never the folks who ought to be worrying about it, in my experience. These are not the kind of faux pas that your garden-variety well-mannered person is likely to commit, if you catch my drift.

The result: polite people end up tiptoeing around conferences, terrified of doing the wrong thing, while the rude stomp around like the football star at the homecoming dance.

Case in point: technologically-savvy reader wrote in to ask if it was considered appropriate to take notes on a laptop or Blackberry during conference seminars. It’s still not very common — surprising, given how computer-bound most of us are these days — but yes, it is acceptable, under two conditions.

First, if you do not sit in a very prominent space in the audience — and not solely because of the tap-tap-tap sound you’ll be making. Believe it or not, it’s actually rather demoralizing for a lecturer to look out at a sea of faces that are all staring at their laps: are these people bored out of their minds, the worried speaker wonders, or just taking notes very intensely?

Don’t believe me? The next time you attend a class of any sort, keep your eyes on the teacher’s face, rather than on your notes, your Blackberry, or that Octavia Butler novel you’ve hidden in your lap because you can’t believe that your boss is making you sit through a talk on the importance of conserving paper clips for the third time this year.

I guarantee that within two minutes, the teacher will be addressing half of her comments directly to you; consistent, animated-faced attention is THAT unusual in a lecture environment. The bigger the class, the more quickly she will focus upon the one audience member who is visibly interested in what she is saying.

In the university department where I used to teach, active listening was so rare that occasionally, one or another of my colleagues would get so carried away with appreciation that he would marry a particularly attentive student. One trembles to think what these men would have done had they been gripping enough lecturers to animate an entire room.

Back to the Blackberry issue. It’s also considered, well, considerate to ask the speaker before the class if it is all right to use any electronic device during the seminar, be it computer or recording device.

Why? Think about it: if your head happens to be apparently focused upon your screen, how is the speaker to know that you’re not just checking your e-mail?

Enough about the presenters’ problems; let’s move on to yours. Do be aware that attending a conference, particularly your first, can be a bit overwhelming. You’re going to want to pace yourself.

“But Anne!” I hear conference brochure-clutching writers out there crying, “The schedule is jam-packed with offerings, many of which overlap temporally! I don’t want to miss a thing!”

Yes, it’s tempting to take every single class and listen to every speaker, but frankly, you’re going to be a better pitcher if you allow yourself to take occasional breaks. Cut yourself some slack; don’t book yourself for the entire time.

Why? Well, let me ask you this: would you rather be babbling incoherently during the last seminar of the weekend, or raising your hand to ask a coherent question?

Before you answer that, let me add: since most attendees’ brains are mush by the end of the conference, it’s generally easier to get close to an agent or editor who teaches a class on the final day. Fewer lines, less competition.

Do make a point of doing something other than lingering in the conference center. Go walk around the block. Sit in the sun. Grab a cup of coffee with that fabulous SF writer you just met. Hang out in the bar that’s never more than 100 yards from any writers’ conference; that tends to be where the already-agented and already-published hang out, anyway.

Skipping the occasional seminar is NOT being lax about pursuing professional opportunities: it is smart strategy, to make sure you’re fresh for your pitches. If you can’t tear yourself away, take a few moments to close your eyes and take a few deep breaths, to reset your internal pace from PANIC! to I’m-Doing-Fine.

I know that I sound like an over-eager Lamaze coach on this point, but I can’t overemphasize the importance of reminding yourself to keep taking deep breaths throughout the conference. A particularly good time for one is immediately after you sit down in front of an agent or editor.

Trust me: your brain could use the oxygen right around then, and it will help you calm down so you can make your most effective pitch.

And at the risk of sounding like the proverbial broken record, please, please, PLEASE don’t expect a conference miracle. Writing almost never sells on pitches alone. You are not going to really know what an agent thinks about your work until she has read some of it.

Translation: it’s almost unheard-of for an agent to sign up a client during a conference. (And no, I have no idea why so many conference-organizers blithely hand out feedback forms asking if you found an agent at the event. Even the most successful conference pitchers generally don’t receive an offer for weeks.)

Remember, your goal here is NOT to be discovered on the spot, but to get the industry pro in front of you to ask to read your writing. Period.

Yes, I know: I’ve said this before. And I’m going to keep saying it as long as there are aspiring writers out there who walk into pitch meetings expecting to hear the agent cry, “My God, that’s the best premise since OLIVER TWIST. Here’s a representation contract — and look, here’s my favorite editor now. Let’s see if he’s interested.”

Then, of course, the editor falls equally in love with it, offers an advance large enough to cover New Hampshire in $20 bills, and the book is out by Christmas. As an Oprah’s Book Club selection, naturally.

Long-time readers, chant along with me now: this is not how the publishing industry works.

The point of pitching is to skip the querying stage and pass directly to the submission stage. So being asked to send pages is a terrific outcome for this situation, not a distant second place to an imaginary reality.

Admittedly, though, that is SO easy to forget in the throes of a pitch meeting. Almost as easy as forgetting that a request to submit is not a promise to represent or publish.

To reiterate: whatever an agent or editor says to you in a conference situation is just a conversation at a conference, not the Sermon on the Mount or testimony in front of a Congressional committee. Everything is provisional until some paper has changed hands.

This is equally true, incidentally, whether your conference experience includes an agent who actually starts drooling visibly with greed while you were pitching or an editor in a terrible mood who raves for 15 minutes about how the public isn’t buying books anymore. Until you sign a mutually-binding contract, no promises — or condemnation, for that matter — should be inferred or believed absolutely.

Try to maintain perspective.

Admittedly, perspective is genuinely hard to achieve when a real, live agent says, “Sure, send me the first chapter,” especially if you’ve been shopping the book around for eons. But it IS vital to keep in the back of your mind that eliciting this statement is not the end of your job as a marketer, because regardless of how much any given agent or editor says she loves your pitch, she’s not going to make an actual decision until she’s read at least part of it.

So even if you are over the moon about positive response from the agent of your dreams, please, I beg you, DON’T STOP PITCHING IN THE HALLWAYS. Try to generate as many requests to see your work as you can.

I’m serious about this. No matter who says yes to you first, you will be much, much happier two months from now if you have a longer requested submissions list. Ultimately, going to a conference to pitch only twice, when there are 20 agents in the building, is just not efficient.

Also, it is VERY much in your interest to send out submissions to several agents at once, rather than one at a time. If several asked, thank your lucky stars and mail those manuscripts to all of them at the same time.

I heard that gasp, but no, there is absolutely nothing unethical about this, unless (a) one of the agencies has a policy precluding multiple submissions (rare) or (b) you promised one agent an exclusive. (I would EMPHATICALLY discourage you from granting (b), by the way — and if you don’t know why, please see the EXCLUSIVES TO AGENTS category at right before you even CONSIDER pitching at a conference.)

Just mention in your cover letter to each that other agents are also reading it; trust me, that’s not going to annoy anyone. That old saw about agents’ getting insulted if you don’t submit one at a time is absolutely untrue; unless an agent ASKS for an exclusive look at your work, it’s neither expected nor in your interest to act as if s/he has.

So there.

Back to why you should keep on pitching in those hallways: it tends to be a trifle easier to get to yes than in a formal pitch. Counter-intuitive, isn’t it? Yet in many ways, casual pitches are easier.

Why? For one simple reason: time. In a hallway pitch, agents will often automatically tell you to submit the first chapter, in order to be able to keep on walking down the hall, finish loading salad onto their plates, or be able to move on to the next person in line after the agents’ forum.

If the agent handles your type of work, the premise is interesting, and you are polite, they will usually hand you their business cards and say, “Send me the first 50 pages.”

Okay, pop quiz to see who has been paying attention to this series so far: after the agent says this, do you:

(a) regard it as an invitation to talk about your work at greater length?

(b) say, “Gee, you’re a lot nicer than Agent X. He turned me down flat,” and go on to give details about how mean he was?

(c) launch into a ten-minute diatribe about the two years you’ve spent querying this particular project?

(d) thank her profusely and vanish in a puff of smoke so you may both pitch again and read the requested pages IN THEIR ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD before you submit them?

If you said anything but (d), go back and reread the Pitching 101 series — and the entirety of the INDUSTRY ETIQUETTE category at right as well. You need to learn what’s considered polite in the industry, pronto.

In a face-to-face pitch in a formal meeting, agents tend to be more selective than in a hallway pitch. (I know; counterintuitive, isn’t it?) Again, the reason is time. In a ten-minute meeting, there is actual leisure to consider what you are saying, to weigh the book’s merits — in short, enough time to save themselves time down the line by rejecting your book now.

Why might this seem desirable to them? Well, think about it: if you send it to them at their request, someone in their office is ethically required to spend time reading it, right? By rejecting it on the pitch alone, they’ve just saved Millicent the screener 5 or 10 minutes.

Also, sitting down in front of an agent or editor, looking her in the eye, and beginning to talk about your book can be quite a bit more intimidating than giving a hallway pitch — it helps to be aware of that in advance, I find. In a perverse way, a formal pitch can be significantly harder to give successfully than a hallway one.

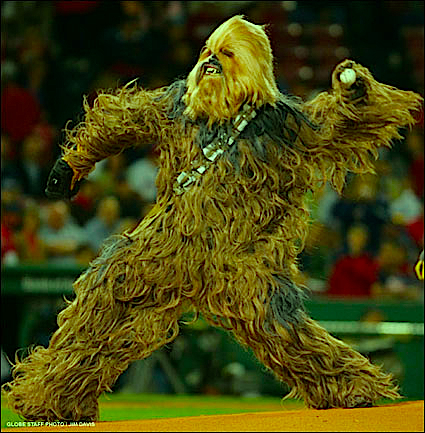

So get out there and pitch, pitch, pitch! Think of it this way: every time you buttonhole an agent and say those magic first hundred words is one less query letter you’re going to need to send out.

Still hanging in there? Still breathing at least once an hour? Good; I’ll move on.

As a veteran of many, many writers’ conferences all over the country, I can tell you from experience that they can be very, very tiring. Especially if it’s your first conference. Just sitting under fluorescent lights in an air-conditioned room for that many hours would tend to leech the life force out of you all by itself, but here, you will be surrounded by a whole lot of very stressed people while you are trying to learn as much as you possibly can.

As you may have noticed, most of my advice on how to cope with all of this ambient stress gracefully is pretty much what your mother probably said to you when you went to your first party: be polite; be nice to yourself and others; watch your caffeine and alcohol intake, and make sure to drink enough water throughout the day. Eat occasionally.

And you’re not wearing THAT, are you?

Oops, slipped too far into Mom mode. Actually, on the only occasion when my mother actually made that comment upon something I was wearing, she had made the frock in question. For my senior prom, she cranked out a backless little number in midnight-blue Chinese silk that she liked to call my “Carole Lombard dress,” for an occasion where practically every other girl was going to be wearing something demure and flouncy by Laura Ashley.

It was, to put it mildly, not what anyone expected the valedictorian to wear she hastened to alter it. Even with the alterations, most of the male teachers followed me around all night long. The last time I bumped into my old chorus teacher, he spontaneously recalled the dress. “A shame that you didn’t dress like that all the time,” he said wistfully.

Oh, what a great dress that was. Oh, how inappropriate it would have been for a writers’ conference — or really, for any occasion that did not involve going out for a big night on the town in 1939. But then, so would those prissy Laura Ashley frocks.

Which brings me back to my point (thank goodness).

I wrote on what you should and shouldn’t wear to a conference at some length in an earlier post, but if you find yourself in perplexity when you are standing in front of your closet, remember this solid rule that will help you wherever you go within the publishing industry: unless you will be attending a black-tie affair, you are almost always safe with what would be appropriate to wear to your first big public reading of your work.

And don’t those of you who have been hanging around the industry for a while wish someone had shared THAT little tidbit with you sooner?

To repeat a bit more motherly advice: do remember to eat something within an hour or two of your pitch meeting. I know that you may feel too nervous to eat. but believe me, if you were going to pick an hour of your life for feeling light-headed, this is not a wise choice. If you are giving a hallway pitch, or standing waiting to go into a meeting, make sure not to lock your knees, so you do not faint. (I’ve seen it happen, believe it or not.)

And practice, practice, practice before you go into your meetings; this is the single best thing you can do in advance to preserve yourself from being overwhelmed. As I pointed out yesterday, you will also be surrounded by hundreds of other writers. Introduce yourself, and practice pitching to them.

Better still, find people who share your interests and get to know them. Share a cookie; talk about your work with someone who will understand. Because, really, is your life, is any writer’s life, already filled with too many people who get what we do? You will be an infinitely happier camper in the long run if you have friends who can understand your successes and sympathize with your setbacks as only another writer can.

I know this from experience, naturally. The first thing I said to many of my dearest friends in the world was, “So, what do you write?”

To which the savvy conference-goer replies — chant it with me now, everyone — the magic first hundred words.

In fact, the first people I told about my first book deal — after my SO and my mother, of course — were people I had met in precisely this manner. Why call them before my college roommate? Because ordinary people, the kind who don’t spend all of their spare time creating new realities out of whole cloth, honestly, truly, sincerely, often have difficulty understanding the pressures and timelines that rule writers’ lives.

Case in point: the FIRST words by mother-in-law uttered after hearing that my book had sold: “What do you mean, it’s not coming out for another couple of years? Why the delay?”

This kind of response is, unfortunately, common. I don’t think any writer ever gets used to seeing her non-writer friends’ faces fall upon being told that the book won’t be coming out for a year, at least, after the sale that’s just happened, or that signing with an agent does not automatically equal a publication contract, or that not every book is headed for the bestseller list.

Thought I got off track from the question of how to keep from getting stressed out, didn’t you? Actually, I didn’t: finding buddies to go through the conference process with you can help you feel grounded throughout.

Not only are these new buddies great potential first readers for your manuscripts, future writing group members, and people to invite to book readings, they’re also folks to pass notes to during talks. (Minor disobedience is a terrific way to blow off steam, I find.) You can hear about the high points of classes you don’t attend from them afterward.

And who wouldn’t rather walk into a room with 300 strangers and one keynote speaker with a newfound chum than alone?

Making friends within the hectic conference environment will help you retain a sense of being a valuable, interesting individual far better than keeping to yourself, and the long-term benefits are endless.

To paraphrase Goethe, it is not the formal structures that make the world fell warm and friendly; friends make the earth feel like an inhabited garden.

So please, for your own sake: make some friends at the conference, so you will have someone to pick up the phone and call when the agent of your dreams falls in love with your first chapter and asks to see the entire book! And get to enjoy the vicarious thrill when your writing friends leap their hurdles, too.

This can be a very lonely business; I can tell you from experience, nothing brightens your day like opening your e-mail when you’re really discouraged to find a message from a friend who’s just sold a book or landed an agent.

Well, okay, I’ll admit it: getting a call from your agent telling you that YOU’ve just sold a book is rather more of a day-brightener. As is the call saying, “I love your work, and I want to represent you.”

But the other is still awfully darned good. Start laying the groundwork for it now.

One more little thing that will help keep you from stressing out too much: while it’s always nice if you can be so comfortable with your pitch that you can give it from memory, it’s probably fair to assume that you’re going to be a LITTLE bit nervous during your meetings.

So do yourself a favor — write it all down; give yourself permission to read it when the time comes, if you feel that will help you. Really, it’s considered perfectly acceptable, and it will keep you from forgetting key points.

I would advise writing on the top of the paper, in great big letters: BREATHE!

Do remember to pat yourself on the back occasionally, too, for being brave enough to put yourself on the line for your work. As with querying and submitting, it requires genuine guts to submit your ideas to the pros; I don’t think writers get enough credit for that.

In that spirit, I’m going to confess: I have one other conference-going ritual, something I do just before I walk into any convention center, anywhere, anytime, either to teach or to pitch. It’s not as nice or as public-spirited as the other techniques I have described, but I find it is terrific for the mental health. I go away by myself somewhere and play at top volume Joe Jackson’s song Hit Single and Jill Sobule’s (I Don’t Want to Get) Bitter.

The former, a charming story about dumbing down a song so it will stand a better chance of making it big on the pop charts, includes the PERFECT lyric to hum walking into a pitch meeting:

And when I think of all the years of finding out

What I already knew

Now I spread myself around

And you can have 3 minutes, too.If that doesn’t summarize the difference between pitching your work verbally and being judged on the quality of the writing itself, I should like to know what does. (Sorry, Joe: I would have preferred to link above to your site, but your site mysteriously doesn’t include lyrics.)

The latter, a song about complaining, concludes with a pretty good mantra for any conference-goer:

So I’ll smile with the rest, wishing everyone the best

And know the one who made it made it because she was actually pretty good.

‘Cause I don’t want to get bitter.

I don’t want to turn cruel.I hum that one a LOT during conferences, I’ll admit. Helpful, I find, when a bestselling author whose agent is her college roommate’s cousin tells a roomful of people who have been querying for the past five years that good writing always finds a home.

Perhaps, but certainly not easily.

What you’re trying to do certainly is not easy, or fun, but you can do it. You’re your book’s best advocate. And remember, all you’re trying to do is to get these nice people to take a look at your writing. No more, no less.

It’s a perfectly reasonable request, and you’re going to be terrific at making it, because you’ve been sensible and brave enough to face your fears and prepare like a professional.

Take a deep breath on me, everyone, and keep up the good work!

(1) As with the keynote and the elevator speech, most pitchers make the mistake of trying to turn the pitch proper into a summary of the book’s plot.

(1) As with the keynote and the elevator speech, most pitchers make the mistake of trying to turn the pitch proper into a summary of the book’s plot. (2) Most pitchers don’t stop talking when their pitches are done.

(2) Most pitchers don’t stop talking when their pitches are done. (3) The vast majority of conference pitchers neither prepare adequately nor practice enough.

(3) The vast majority of conference pitchers neither prepare adequately nor practice enough. (4) Most pitchers harbor an absurd prejudice in favor of memorizing their pitches, and thus do not bring a written copy with them into the pitch meeting.

(4) Most pitchers harbor an absurd prejudice in favor of memorizing their pitches, and thus do not bring a written copy with them into the pitch meeting. (5) Most pitchers don’t realize until they are actually in the meeting that part of what they are demonstrating in the 2-minute pitch is their acumen as a storyteller. If, indeed, they realize it at all.

(5) Most pitchers don’t realize until they are actually in the meeting that part of what they are demonstrating in the 2-minute pitch is their acumen as a storyteller. If, indeed, they realize it at all. (6) Few pitches capture the voice of the manuscript they ostensibly represent.

(6) Few pitches capture the voice of the manuscript they ostensibly represent.  (7) Very few pitches include intriguing, one-of-a-kind details.

(7) Very few pitches include intriguing, one-of-a-kind details.  (8) Most pitchers assume that a pitch-hearer will hear — and digest — every word they say, yet the combination of pitch fatigue and hectic pitch environments virtually guarantee that will not be the case.

(8) Most pitchers assume that a pitch-hearer will hear — and digest — every word they say, yet the combination of pitch fatigue and hectic pitch environments virtually guarantee that will not be the case. (9) Few pitchers are comfortable enough with their pitches not feel thrown off course by follow-up questions.

(9) Few pitchers are comfortable enough with their pitches not feel thrown off course by follow-up questions. (10) Far too many pitchers labor under the false impression that if an agent or editor likes a pitch, s/he will snap up the book on the spot. In reality, they’re going to want to read the manuscript first.

(10) Far too many pitchers labor under the false impression that if an agent or editor likes a pitch, s/he will snap up the book on the spot. In reality, they’re going to want to read the manuscript first. If the agent is interested by your pitch, she will hand you her business card and ask you to send some portion of the manuscript — usually, the first chapter, the first 50 pages, or for nonfiction, the book proposal. If she’s very, very enthused, she may ask you to mail the whole thing.

If the agent is interested by your pitch, she will hand you her business card and ask you to send some portion of the manuscript — usually, the first chapter, the first 50 pages, or for nonfiction, the book proposal. If she’s very, very enthused, she may ask you to mail the whole thing.

PS: lovers of fluffy bunnies and winsome chicks should make sure to visit Author! Author this weekend, when we will be visited by a guest blogger I’ve been hoping for a long time would join us here. As some of you may have begun to suspect over the past few days, I’m pretty excited about the prospect.

PS: lovers of fluffy bunnies and winsome chicks should make sure to visit Author! Author this weekend, when we will be visited by a guest blogger I’ve been hoping for a long time would join us here. As some of you may have begun to suspect over the past few days, I’m pretty excited about the prospect.