Wouldn’t you have assumed, campers, that yesterday’s little foray into obscure editorial pet peeves would have worked some nit-picking vim out of my system? Not so, apparently. This evening, my dinner companion and I made the mistake of allowing the waitress in our neighborhood sushi place to seat us near a comely matron lecturing her rather obnoxious college-age daughters. They lectured right back at her, sometimes simultaneously. All three spoke in tones that, while perhaps not quite capable of waking the dead, would at least prompt the critically wounded to drag themselves bodily into another room, if not another county, in order to escape the non-stop barrage of chatter.

And you know how I’m always pointing out that while realistic dialogue is wonderful on the page, real-life dialogue tends to be stultifying, due to its tendency to repeat itself? Had this trio been providing the listen and repeat audio for a college language lab, they could hardly have reused phrases more. Adding to the fun, the younger daughter had such an unparalleled gift for cliché that the average greeting card would have found her observations unbearably banal.

Since carrying on a conversation at our table was hopeless, I did what any self-respecting editor would have done: toyed with my asparagus tempura and mentally trimmed entire paragraphs out of the dialogue blasting through the restaurant. I was busily engaged in running a mental red pencil line through the younger daughter’s third “you can’t judge a man until you walk a mile in his moccasins” of the evening when the mother’s monologue veered abruptly into a discussion of DON QUIXOTE.

Frankly, I thought that I was dreaming (speaking of clichés). Although the lady seemed to have trouble recalling author’s name, her analysis was surprisingly trenchant — so much so that I almost stopped editing it. (The younger daughter’s frequent observation that the book was a classic still had to go, however.) She began talking about how a young friend of hers had responded to the book. It sounded as though they might have been reading it together.

She referred to her co-reader as — oh, I tremble to relate it — her mentee. As in the person who sits at the feet of a mentor, drinking in wisdom.

I couldn’t stand it anymore. “Protégé,” I said, loudly enough to be heard over the ambient din. “You mean protégé. Unless, of course, you are referring to the Mentor of classical myth, in which case the student would be Telemachus.”

Dead silence from the other table, but several other diners spontaneously burst into applause. The mother waved frantically at the waitress for her check.

As they left, glaring at me viciously, I thought about informing them that the author of DON QUIXOTE was Miguel Cervantes. But as he wrote the immortal line, “A closed mouth catches no flies,” I thought better of it.

See to what extremes a life of editing drives otherwise perfectly reasonable people? Naturally, I was aware that the mother had not coined the term mentee on the spot; based on her highly redundant anecdotal style, she lacked the essential creativity to add a new word to the language. It’s one of those annoying business-speak terms that has somehow worked its way into everyday speech. I might have let it pass had the speaker and her progeny not spent half an hour boring me and everyone else in the restaurant to the verge of extinction.

That level of touchiness is roughly what the average pitch-hearer reaches by the tenth or twelfth similar pitch of the conference. By the fiftieth or sixtieth, she’s not only ready to correct the verbal gaffes of passersby — she’s praying that some kind muse will take pity on her and drop an anvil on her head. Anything, so she does not have to listen to yet another cliché-ridden summary of a plot that sounds suspiciously like the first TWILIGHT book.

Chant it with me now, campers: the first rule of pitching is thou shalt not bore. The second is the pitcher is there to hear your original ideas and language. Stock phrases, no matter how apt, are unlikely to make your premise shine; a description so general that your book will merge in the hearer’s mind with a dozen others is not the best way to make yours memorable.

You’re a writer, are you not? Is there a reason that your pitch should not demonstrate that you have some talent in that direction?

Why, we were just talking about that, weren’t we? Last time, I went over the basic format of a 2-minute pitch, the kind a writer is expected to give within the context of a scheduled pitch meeting. Unlike the shorter elevator speech or hallway pitch, the formal pitch is intended not merely to pique the hearer’s interest in the book, but to convey that the writer is one heck of a storyteller, whether the book is fiction or nonfiction.

In case that’s too subtle for anyone, I shall throw a brick through the nearest window and shout: no matter what kind of prose you write, your storytelling skills are part of what you are selling here.

How might a trembling author-to-be demonstrate those skills? Basically, by dolling up her elevator speech with simply fascinating details and fresh twists that will hold the hearer in thrall.

At least for two minutes. After that, the agent’s going to have to ask to read your book to find out what happens.

Because sounding scintillating to the pitch-fatigued is a genuinely tall order, it is absolutely vital that you prepare for those two minutes in advance, either timing yourself at home or by buttonholing like-minded writers at the conference for mutual practice. Otherwise, as I mentioned in passing last time, it is very, very easy to start rambling once you are actually in your pitch meeting.

Frankly, the length of the pitch appointment typically doesn’t allow any time for rambling or free-association. Rambling, unfortunately, tends to lead the pitcher away from issues of marketing and into the kind of free-form discussion he might have with another writer. All too often, pitchers will digress into artistic-critical questions (“What do you think of multiple protagonists in general?”), literary-philosophical issues (“I wanted to experiment with a double identity in my romance novel, because I feel that Descartian dualism forms the underpinnings of the modern Western love relationship.”), and autobiographical observations (“I spent 17 years writing this novel. Please love it, or I shall impale myself on the nearest sharp object.”) .

Remember, you are marketing a product here: talk of art and theory can come later, after you’ve signed a contract with this agent or that editor. For now, your job is to wow ‘em with the originality of your book concept, the freshness of your approach, and the evocative language of your pitch.

Don’t forget that that the formal pitch is, in fact, is an extended, spoken query letter; it should contain, at minimum, the same information. Like any good promotional speech, it also needs to present the book as both unique and memorable.

Oh, you would like to know how to go about that, would you? Glad you asked. Time to whip out one of my famous lists of tips.

(1) Emphasize the most original parts of your story or argument

One great way to increase the probability of its seeming both is to include beautifully-phrased telling details from the book, something that the agent or editor is unlikely to hear from anybody else. What specifics can you use to describe your protagonist’s personality, the challenges he faces, the environment in which he functions, that render each different from any other book currently on the market?

See why I suggested earlier in this series that you might want to gain some familiarity with what is being published right now in your book category? Unless you know what’s out there, how can you draw a vibrant contrast?

I sense a touch of annoyance out there, don’t I? “But Anne,” a disgruntled soul or two protests, “I understand that part of the point here is to present my book concept as fresh, but I’m going to be talking about my book for two minutes, at best. Do I really want to waste my time on a compare-and-contrast exercise when I could be showing (not telling) that my book is in fact unique?”

Well, I wasn’t precisely envisioning that you embark upon a master’s thesis on the literary merits of the current thriller market; what I had in mind was your becoming aware enough of the current offerings to know what about your project is going to seem most unusual to someone who has been marinating in the present offerings for the last couple of years.

Regardless of how your book is fresh, you’re going to want to be as specific as possible about it. Which leads me to…

(2) Include details that the hearer won’t be expecting.

Think back to the elevator speech I developed earlier in this series for PRIDE AND PREJUDICE. How likely is it that anybody else at the conference will be pitching a story that includes a sister who talks philosophy while pounding on the piano, or a mother who insists her daughter marry a cousin she has just met?

Not very — which means that including these details in the pitch is going to surprise the hearer a little. And that, in turn, will render the pitch more memorable.

(3) Broaden your scope a little.

In a hallway pitch, of course, you don’t have the luxury of including more than a couple of rich details, but the 2-minute pitch is another kettle of proverbial fish. You can afford the time to flesh out the skeleton of your premise and story arc. You can, in fact, include a small scene.

So here’s a wacky suggestion: take fifteen or twenty seconds of those two minutes to tell the story of ONE scene in vivid, Technicolor-level detail.

I’m quite serious about this. It’s an unorthodox thing to do in a pitch, but it works all the better for that reason, if you can keep it brief AND fresh.

Yes, even if the book in question is a memoir — or a nonfiction book about an incident that took place in 512 BC, for that matter. To render any subject interesting to a reader, you’re going to need to introduce an anecdote or two. This is a fabulous opportunity to flex your show-don’t-tell muscles.

Which is, if you think about it, why a gripping story draws us in: good storytelling creates the illusion of being there. By placing the pitch-hearer in the middle of a vividly-realized scene, you make him more than a listener to a summary — you let him feel a part of the story.

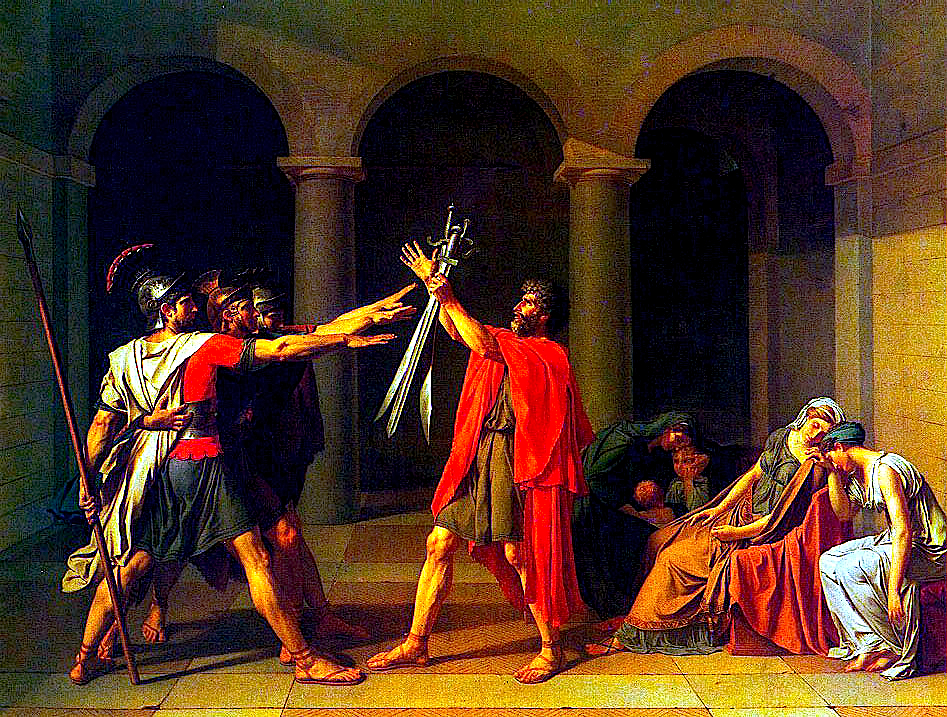

(4) Borrow a page from Scheherazade’s book: don’t tell too much of the story; leave the hearer wanting more.

Remember, the pitcher’s job is not to summarize the plot or argument — it’s to present it in a fascinating manner. After all, the point of the pitch is to convince the agent or editor to ask to read the manuscript, right? So focusing on making the premise sound irresistible is usually a better plan than trying to cram the entire story arc into a couple of breathless paragraphs.

Don’t be afraid to introduce a cliffhanger at the end of your pitch– scenarios that leave the hearer wondering how the heck is this author going to get her protagonist out of THAT situation? can work very, very well in this context.

(5) Axe the jargon.

Many pitchers (and queriers, actually) assume, wrongly, that if their manuscripts are about people who habitually use an industry-based jargon, it will make their pitches more credible if that language permeates the 2-minute speech. In fact, the opposite is generally true: terminology that excludes outsiders usually merely perplexes the pitch hearer.

Remember, it’s never safe to assume that any given agent or editor (or Millicent, for that matter) has any background in your chosen subject matter. It would behoove you, then, to use language in your pitch that everybody in the publishing industry can understand.

Unless, of course, your book is about the publishing industry, in which case you may be as jargon-ridden as you like.

(6) Delve into the realm of the senses.

Another technique that helps elevate memorability: including as many sensual words and images as you can in your pitch. Not sexual ones, necessarily, but referring to the operation of the senses. As anyone who has spent even a couple of weeks reading submissions or contest entries can tell you, the vast majority of writing out there sticks to the most obvious senses — sight and sound — probably because these are the two to which TV and movie scripts are limited.

So a uniquely-described scent, taste, skin sensation, or pricking of the sixth sense does tend to be memorable. I just mention.

How might you go about this, you ask? Comb the text itself. Is there an indelible visual image in your book? Work it in. Are birds twittering throughout your tropical romance? Let the agent hear them. Is your axe murderer concentrating his professional efforts on chefs? We’d better taste some fois gras.

And so forth. The goal here is to include a single original image or scene in sufficient detail that the agent or editor will think, “Wow, I’ve never heard that before,” and ask to read the book.

Which leads me to ask those of you whose works are still in the writing phase: are there places in your manuscript where you could beef up the comic elements, sensual details, elegant environmental descriptions, etc., to strengthen the narrative and to render the book easier to pitch when its day comes?

Just something to ponder.

(7) Make sure that your pitch contains at least one detailed, memorable image.

There is a terrific example of such a pitch in the Robert Altman film THE PLAYER, should you have time to check it out before the next time you plan to pitch. The protagonist is an executive at a motion picture studio; throughout the film, he hears many pitches. One unusually persistent director chases the executive all over the greater LA metro area, trying to get him to listen to his pitch. (You’re in exactly the right mental state to appreciate that now, I’m guessing.) Eventually, the executive gives in, and tells the director to sell him the film in 25 words or less.

Rather than launching into the plot of the film, however, the director does something interesting: he spends a good 30 seconds setting up the initial visual image of the film: a group of protestors holding a vigil outside a prison during a rainstorm, their candles causing the umbrellas under which they huddle to glow like Chinese lanterns.

”That’s nice,” the executive says, surprised. “I’ve never seen that before.”

Pitching success!

If a strong, memorable detail of yours can elicit this kind of reaction from an agent or editor, you’re home free. Give some thought to where your book might offer up the scene, sensual detail, or magnificently evocative sentence that will make ‘em do a double-take.

Or a spit-take, if your book is a comedy. Which brings me to…

(8) Let the tone of the pitch reflect the tone of the book.

This one’s just common sense, really: an agent or editor who likes a particular kind of book enough to handle it routinely may reasonably be expected to admire that kind of writing, right? So why not write the pitch in the tone and language you already know has pleased this person in the past?

A good pitch for a funny book makes its premise seem amusing; a great pitch contains at least one line that provokes a spontaneous burst of laughter from the hearer. By the same token, while a good pitch for a romance would make it sound like a fun read, a great pitch might prompt the hearer to say, “Is it getting hot in here?”

Getting the picture?

I’m tempted to sign off for the day to allow all of you to rush off to stuff your pitches to the gills with indelible imagery, sensual details, and book category-appropriate mood-enhancers, but I know from long experience teaching writers to pitch that some of your manuscripts will not necessarily fit comfortably into the template I’ve laid out over the last couple of posts. To head off one of the more common problems at the pass, I’m going to revive a reader’s excellent question about the pitch proper from years past. (Keep ‘em coming, folks!)

Somewhere back in the dim mists of time, sharp-eyed reader Colleen wrote in to ask how one adapts the 2-minute pitch format to stories with multiple protagonists — a more difficult task than it might appear at first glance. By definition, it would be pretty hard to pitch it as just one of the characters’ being an interesting person in an interesting situation; in theory, a good multiple-protagonist novel is the story of LOTS of interesting people in LOTS of interesting situations.

So what’s the writer to do? Tell the story of the book in the pitch, not the stories of the various characters.

Does that sound like an oxymoron? Allow me to explain. For a novel with multiple protagonists to work, it must have an underlying unitary story — it has to be, unless the chapters and sections are a collection of unrelated short stories. (Which would make it a short story collection, not a novel, and should be pitched as such.) Even if it is told from the point of view of many, many people, there is pretty much always some point of commonality.

That area of commonality should be the focus of your pitch, not how many characters’ perspectives it takes to tell it. Strip the story to its basic elements, and pitch that.

Those of you juggling many protagonists just sighed deeply, didn’t you? “But Anne,” lovers of group dynamics everywhere protest, “why should I limit myself to the simplest storyline? Doesn’t that misrepresent my book?”

Not more than other omissions geared toward pitch brevity — you would not, for instance, take up valuable pitching time in telling an agent that your book was written in the third person, would you? (In case the answer isn’t obvious: no, you shouldn’t. Let the narrative choices reveal themselves when the agent reads your manuscript.) Even in the extremely unlikely event that your book is such pure literary fiction that the characters and plot are irrelevant, concentrating instead upon experiments in writing style, your book is still about something, isn’t it?

That something should be the subject of your pitch. Why? Because any agent is going to have to know what the book is about in order to interest an editor in it. And it’s unlikely to the point of hilarity that she’ll stop you immediately after you say, “Well, my novel is told from the perspectives of three different protagonists…” with a curt, “I’ve heard enough; I’ve been looking for a good multiple-perspective novel. Allow me to sign you on the spot.”

How you have chosen to construct the narrative is not information that should be in your pitch. The agent or editor is going to want to know what the book is about.

“Okay,” the sighers concede reluctantly, “I can sort of see that, if we want to reduce the discussion to marketing terms. But I still don’t understand why simplifying my extraordinarily complex plot would help my pitch.”

Well, there’s a practical reason — and then there’s a different kind of practical reason. Let’s take the most straightforward one first.

From a pitch-hearer’s point of view, once more than a couple of characters have been introduced within those first couple of sentences, new names tend to blur together like extras in a movie, unless the pitcher makes it absolutely clear how they are all tied together. Typically, therefore, they will assume that the first mentioned by name is the protagonist.

So if you started to pitch a multiple protagonist novel on pure plot — “Bernice is dealing with trying to run a one-room schoolhouse in Morocco, while Harold is coping with the perils of window-washing in Manhattan, and Yvonne is braving the Arctic tundra…” — even the most open-minded agent or editor is likely to zone out. There’s just too much to remember.

And if remembering three names in two minutes doesn’t strike you as a heavy intellectual burden, please see my earlier post on pitch fatigue.

It’s easy to forget that yours is almost certainly not the only pitch that agent or editor has heard within the last 24 hours, isn’t it, even if you’re not trying to explain a book with several protagonists? Often, pitchers of multiple-protagonist novels will make an even more serious mistake than overloading their elevator speeches with names. They will frequently begin by saying, “Okay, so there are 18 protagonists…”

Whoa there, Sparky. Did anyone in the pitching session ASK about your perspective choices?

Actually, from the writer’s point of view, there’s an excellent reason to include this information: the different perspectives are an integral part of the story being told. Thus, the reader’s experience of the story is going to be inextricably tied up with how it is written.

But that doesn’t mean that this information is going to be helpful to your pitch. I mean, you could conceivably pitch Barbara Kingsolver’s multiple-narrator THE POISONWOOD BIBLE as:

A missionary takes his five daughters and one wife to the middle of Africa. Once they manage to carve out a make-do existence in a culture that none of them really understand, what little security the daughters know is ripped from them, first by their father’s decreasing connection with reality, then by revolution.

That isn’t a bad summary of the plot, but it doesn’t really give much of a feel for the book, does it? The story is told from the perspectives of the various daughters, mostly, who really could not agree on less and who have very different means of expressing themselves.

And that, really, is the charm of the book. But if you’ll take a gander at Ms. Kingsolver’s website, you’ll see that even she (or, more likely, her publicist) doesn’t mention the number of narrators until she’s already set up the premise.

Any guesses why?

Okay, let me ask the question in a manner more relevant to the task at hand: would it be a better idea to walk into a pitch meeting and tell the story in precisely the order it is laid out in the book, spending perhaps a minute on one narrator, then moving on to the next, and so on?

In a word, no. Because — you guessed it — it’s too likely to confuse the hearer.

Hey, do you think that same logic might apply to any complicated-plotted book? Care to estimate the probability that a pitch-fatigued listener will lose track of a grimly literal chronological account of the plot midway through the second sentence?

If you just went pale, would-be pitchers, your answer was probably correct. Let’s get back to Barbara Kingsolver.

Even though the elevator speech above for THE POISONWOOD BIBLE does not do it justice, if I were pitching the book (and thank goodness I’m not; it would be difficult), I would probably use it, with a slight addition at the end:

A missionary takes his five daughters and one wife to the middle of Africa. Once they manage to carve out a make-do existence in a culture that none of them really understand, what little security the daughters know is ripped from them, first by their father’s decreasing connection with reality, then by revolution. The reader sees the story from the very different points of view of the five daughters, one of whom has a mental condition that lifts her perceptions into a completely different realm.

Not ideal, perhaps, but it gets the point across, without presenting the perspective choice as the most important thing about the book.

But most pitchers of multiple POV novels are not nearly so restrained, alas. They charge into pitch meetings and tell the story as written in the book, concentrating on each perspective in turn as the agent or editor stares back at them dully, like a bird hypnotized by a snake.

And ten minutes later, when the meeting is over, the writers have only gotten to the end of Chapter 5. Out of 27.

I can’t even begin to estimate how often I experienced this phenomenon in my pitching classes, when I was running the late lamented Pitch Practicing Palace at the Conference-That-Shall-Remain-Nameless, and even when I just happen to be passing by the pitch appointment waiting area at conferences. All too often, first-time pitchers have never talked about their books out loud before — a BAD idea– and think that the proper response to the innocent question, “So what’s your book about?” is to reel off the entire plot.

And I do mean ENTIRE. By the end of it, an attentive listener would know not only precisely what happened to the protagonist and the antagonist, but the neighbors, the city council, and the chickens at the local petting zoo until the day that all of them died.

Poor strategy, that. If you go on too long, they may well draw some unflattering conclusions about the pacing of your storytelling preferences, if you catch my drift.

This outcome is at least 27 times more likely if the book being pitched happens to be a memoir or autobiographical novel, incidentally. Again, bad idea. Because most memoir submissions are episodic, rather than featuring a strong, unitary story arc, a rambling pitching style is likely to send off all kinds of warning flares in a pitch-hearer’s mind.

And trust me, “Well, it’s based on something that actually happened to me…” no longer seems like a fresh concept the 783rd time an agent or editor hears it.

Word to the wise: keep it snappy, emphasize the storyline, and convince the hearer that your book is well worth reading before you even consider explaining why you decided to write it in the first place. And yes, both memoirists and writers of autobiographical fiction work that last bit into their pitches all the time. Do not emulate their example; it may be unpleasant to face, but nobody in the publishing industry is likely to care about why you wrote a book until after they’ve already decided that it’s marketable. (Sorry to be the one to break that to you.)

Which brings me to the second reason that it’s better to tell the story of the book, rather than the stories of each of the major characters: POV choices are a writing issue, not a storyline issue per se. While you will want to talk about some non-story elements in your pitch — the target audience, the selling points, etc. — most of the meat of the pitch is about the story (or, in the case of nonfiction, the argument) itself.

In other words, the agent or editor will learn how you tell the story from reading your manuscript; during the pitching phase, all they need to hear is the story.

Don’t believe me? When’s the last time you walked into a bookstore, buttonholed a clerk, and asked, “Where can I find a good book told from many points of view? I don’t care what it’s about; I just woke up this morning yearning for multiplicity of perspective.”

I thought not. Although if you want to generate a fairly spectacular reaction in a bored clerk on a slow day, you could hardly ask a better question.

Dig deep for those memorable details, everybody, and keep up the good work!

(1) As with the keynote and the elevator speech, most pitchers make the mistake of trying to turn the pitch proper into a summary of the book’s plot, rather than a teaser for its premise.

(1) As with the keynote and the elevator speech, most pitchers make the mistake of trying to turn the pitch proper into a summary of the book’s plot, rather than a teaser for its premise. (2) Most pitchers don’t stop talking when their pitches are done.

(2) Most pitchers don’t stop talking when their pitches are done. (3) The vast majority of conference pitchers neither prepare adequately nor practice enough.

(3) The vast majority of conference pitchers neither prepare adequately nor practice enough. (4) Most pitchers harbor an absurd prejudice in favor of memorizing their pitches, and thus do not bring a written copy with them into the pitch meeting.

(4) Most pitchers harbor an absurd prejudice in favor of memorizing their pitches, and thus do not bring a written copy with them into the pitch meeting. (5) Most pitchers don’t realize until they are actually in the meeting that part of what they are demonstrating in the 2-minute pitch is their acumen as storytellers. If, indeed, they realize it at all.

(5) Most pitchers don’t realize until they are actually in the meeting that part of what they are demonstrating in the 2-minute pitch is their acumen as storytellers. If, indeed, they realize it at all. (6) Few pitches capture the voice of the manuscript they ostensibly represent. Instead, they tend to sound generic or vague.

(6) Few pitches capture the voice of the manuscript they ostensibly represent. Instead, they tend to sound generic or vague.

(8) Very few pitches include intriguing, one-of-a-kind details that set the book being pitched apart from all others.

(8) Very few pitches include intriguing, one-of-a-kind details that set the book being pitched apart from all others. (9) Most pitchers assume that a pitch-hearer will hear — and digest — every word they say, yet the combination of pitch fatigue and hectic pitch environments virtually guarantee that will not be the case.

(9) Most pitchers assume that a pitch-hearer will hear — and digest — every word they say, yet the combination of pitch fatigue and hectic pitch environments virtually guarantee that will not be the case. (10) Few pitchers are comfortable enough with their pitches not feel thrown off course by follow-up questions.

(10) Few pitchers are comfortable enough with their pitches not feel thrown off course by follow-up questions. (11) Far too many pitchers labor under the false impression that if an agent or editor likes a pitch, s/he will snap up the book on the spot. In reality, the agent or editor is going to want to read the manuscript first.

(11) Far too many pitchers labor under the false impression that if an agent or editor likes a pitch, s/he will snap up the book on the spot. In reality, the agent or editor is going to want to read the manuscript first. If the agent is interested by your pitch, she will hand you her business card and ask you to send some portion of the manuscript — usually, the first chapter, the first 50 pages, or for nonfiction, the book proposal. If she’s very, very enthused, she may ask you to mail the whole thing.

If the agent is interested by your pitch, she will hand you her business card and ask you to send some portion of the manuscript — usually, the first chapter, the first 50 pages, or for nonfiction, the book proposal. If she’s very, very enthused, she may ask you to mail the whole thing.

As of this moment, you have my permission to get into an elevator with an agent or editor without pitching, if you so desire. Live long and prosper.

As of this moment, you have my permission to get into an elevator with an agent or editor without pitching, if you so desire. Live long and prosper. I hereby solemnly swear that I shall not have learned the magic first hundred words and elevator speech in vain. The next time I attend a writers’ conference, I will pitch to at least three agents or editors with whom I do not have a previously-scheduled appointment.

I hereby solemnly swear that I shall not have learned the magic first hundred words and elevator speech in vain. The next time I attend a writers’ conference, I will pitch to at least three agents or editors with whom I do not have a previously-scheduled appointment. MAGIC FIRST 100 WORDS + ELEVATOR SPEECH = HALLWAY PITCH.

MAGIC FIRST 100 WORDS + ELEVATOR SPEECH = HALLWAY PITCH.