Yes, I’m still singing the blues today. Why do you ask?

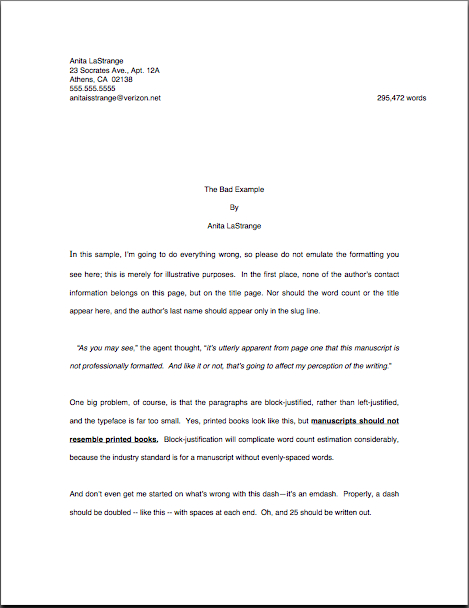

Actually, I’m feeling a little better, thanks. Writing yesterday’s post reminded me just how comforting it is that there are SOME constants in the ever-changing literary world; unfortunately, many of the unchanging verities don’t exactly work in the aspiring writer’s favor. Expecting everyone who has ever had a good book idea to know — by magic, presumably — about standard format for manuscripts, for instance; those rules haven’t changed much in 30 years, but how is a brand-new submitter to know that?

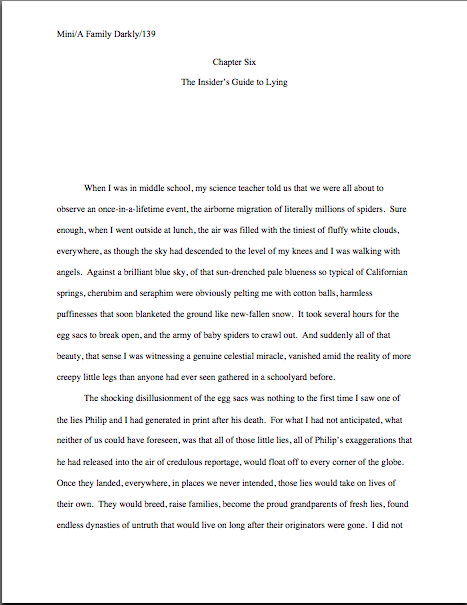

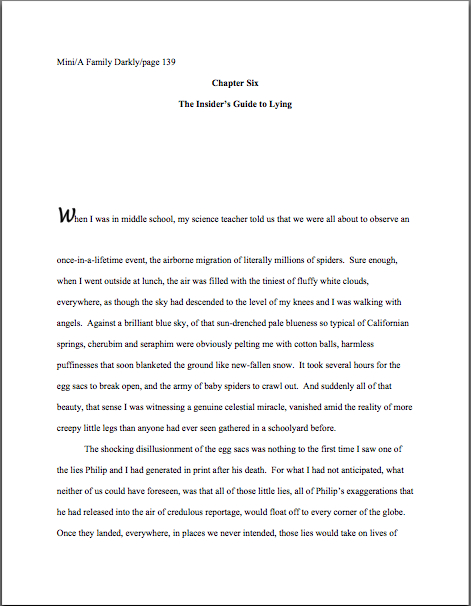

That question was one reason I started this blog. So if you’re new to the game and by some remarkable chance the format fairy has not yet visited you in the night to tuck a list of manuscript rules under your pillow, run, don’t walk, I implore you, to the STANDARD FORMAT BASICS and/or STANDARD FORMAT ILLUSTRATED categories on the list at right.

In my capacity as stand-in for the format fairy, I’m going to move on with the ins and outs of author bios.

As those of you who sat through yesterday’s long, rambling, but I hope entertainingly persuasive post already know, the necessity of writing an author bio is often sprung upon an aspiring writer. Not in a delightful, hands-over-the-eyes way, but in brusque, business-like manner: “You’ll have it to me in the morning, right?” requesting agents and editors are prone to say. “You can just e-mail it to me now, of course?”

Some writers never get the resulting lump out of their throats again.

Those of us who have been at the writing game for a while have learned not to voice dismay at this kind of request. Surviving in the ultra-competitive literary environment is just easier for be an upbeat, can-do kind of writer, the sort who says, “Rewrite WAR AND PEACE by Saturday? No problem!” than the kind who moans and groans over each unreasonable deadline.

Hey, the energy that you expend in complaining about an outrageous request could be put to good use in trying to meet that deadline. As the late great Billie Holiday so often sang,

The difficult

I’ll do right now.

The impossible/will take a little while.

(Will it vitiate my moral too much if I add that the name of the song was “Crazy, He Calls Me”? Clearly, Billie must have spent a lot of time with my agent.)

I also spent yesterday, if memory serves, encouraging you to put together an author bio for yourself as soon as possible, against the day that you might need to produce one, immediately and apparently effortlessly, in response to a request from an agent or editor.

I know, I know: we writers are expected to produce a LOT on spec; it would be nice, especially for a fiction writer, to be able to wait to write SOMETHING affiliated with one’s first book after an advance was already cooling its little green heels in one’s bank account.

Trust me, at that point, you’ll be asked to write more for your publisher’s marketing department, a whole lot more –heck, if you’re a nonfiction writer, you’ll be asked write the rest of the book you proposed — so you’ll be even happier to have one task already checked off the list.

Get the bio out of the way now.

Even if the happy day that you’re juggling the demands of your publishers’ many departments seems impossibly far away to you, think of bio-writing as another tool added to your writer’s toolkit. Not only the bio itself, although it’s certainly delightful to have one on hand when the time comes, but the highly specialized skills involved in writing one.

I’m deadly serious about this — just knowing in your heart that you already have the skills to write this kind of professional document can be marvelously comforting. Every time I have a tight deadline, I am deeply, passionately grateful that I have enough experience with the trade to be able crank out the requisite marketing materials with the speed of a high school junior BSing on her English Literature midterm. It’s definitely a learned skill, acquired through having produced a whole lot of promotional materials for my work (and my clients’, but SHHH about that) over the last decade.

At this point, I can make it sound as if all of human history had been leading exclusively and inevitably to my acquiring the knowledge, background, and research materials for me to write the project in question. The Code of Hammurabi, you will be pleased to know, was written partially with my book in mind.

Which book, you ask, since I have several in progress? Which one would you like to acquire for your publishing house, Mr. or Ms. Editor?

A word to the wise, though: your author bio, like any other promotional material for a book, is a creative writing opportunity. Not an invitation to lie, of course, but a chance to show what a fine storyteller you are.

This is true in spades for NF book proposals, by the way, where the proposer is expected to use her writing skills to paint a picture of what does not yet exist, in order to call it into being. Contrary to popular opinion (including, I was surprised to learn recently, my agent’s — I seem to be talking about him a lot today, don’t I? — but I may have misunderstood him), the formula for a NF proposal is not

good idea + platform = marketable proposal

regardless of the quality of the writing, or even the ever-popular recipe

Take one (1) good idea and combine with platform; stir until well blended. Add one talented writer (interchangable; you can pick ‘em up cheaply anywhere) and stir.

Just as which justice authors a Supreme Court decision affects how a ruling is passed down to posterity, the authorship of a good book proposal matters. Or should, because unlike novels, which are marketed only when already written (unless it’s part of a multi-book deal), NF books exist only in the mind of the author until they are written. That’s why it’s called a proposal, and that’s why it includes an annotated table of contents: it is giving a picture of the book that already exists in the author’s mind.

For those of you who don’t already know, book proposals — the good ones, anyway — are written as if the book being proposed were already written; synopses, even for novels, are written in the present tense. It is your time to depict the book you want to write as you envision it in your fondest dreams.

Since what the senior President Bush used to call “the vision thing” is thus awfully important to any book, particularly a NF one, the author bio that introduces the writer to the agents and editors who might buy the book is equally important. It’s the stand-in for the face-to-face interview for the job you would like a publisher to hire you to do: write a book for them.

The less of your writing they have in front of them when they are making that hiring decision — which, again, is usually an entire book in the case of a novel, but only a proposal and a sample chapter for nonfiction, even for memoir — the more they have to rely upon each and every sentence that’s there, obviously. Do you really want the ones that describe your background to be ones that you wrote in 45 minutes in the dead of night so you could get your submission into the mail before you had to be at work in the morning?

Let me answer that one for you: no, you don’t.

I mention all of this as inducement to you to write up as many of the promotional parts of your presentation package well in advance of when you are likely to be asked for them. This is a minority view among writers, I know, but I would not dream of walking into any writers’ conference situation (or even cocktail party) where I am at all likely to pitch my work without having polished copies of my author bio, synopsis, and a 5-page writing sample nestled securely in my shoulder bag, all ready to take advantage of any passing opportunity.

Chance favors the prepared backpack, as Louis Pasteur is rumored to have said. Or at least something very, very like it.

Once you’ve been asked to give an unexpected pitch at 3:30 in the morning to a bleary-eyed, heavy-drinking editor at an industry party, believe me, you never go near walk out the door unprepared. (The request, incidentally, was made by my agent, who is apparently always looking out for our joint interests, bless his book-mongering heart. Unless he was trying to barter my company for the evening in exchange for reading another client’s work; I’ve never been precisely sure.)

Are you chomping at the bit to get at your own author bio yet? Good. Then you are in the perfect mindset for your homework assignment: start thinking about all of the reasons you are far more interesting than anyone else on the planet.

I’m serious — and I’m not talking about boasting; I’m talking about uniqueness. What makes you different from anyone else who might have written the book you are trying to sell?

Don’t worry for the moment about how, or even whether, these things have any direct connection to the subject matter of the book you’re writing or don’t sound like very impressive credentials. Just get ready to tell me — and the world! — how precisely you are different from everybody else currently scurrying across the face of the planet.

Don’t tell me that you’re not. I shan’t believe it. Why? Because I know, as surely as if I could stand next to God and take an in-depth reading of each and every one of your psyches, that there is no one out there more truly interesting than someone who has devoted her or his life to the pursuit of self-expression. I’ve met writers I didn’t like, certainly, but I’ve never met a genuinely boring one.

Okay, so maybe I need to get out more. I spend an awful lot of time at my keyboard, expressing myself.

We’ll put those lists of attributes to good use next time, I promise. In the meantime, I’ll keep singing the blues, and keep up the good work!