For the last couple of posts, I’ve been encouraging you — yes, YOU, you fabulous writer — to mine your background for intrigue-producing tidbits for your author bio. Not for its own sake, mind you: the creation of a lengthy list of everything about you that either:

1. Renders you the best possible candidate currently wandering the earth’s surface for writing your particular book (and no, novelists and memoirists, you may NOT skip this step), or

2. Renders you fascinating in any way perceptible to a person of at least average intelligence.

is merely the first step in the creation of a stellar author bio to tuck into your query or submission packets.

Why bother? Because an author bio that doesn’t make the author sound interesting is an author bio that’s not going to be all that helpful to Millicent the agency screener when trying to decide whether to recommend that her boss, the agent of your dreams, invest serious time in reading your manuscript or book proposal or to reject your query or submission. While it is necessary to be terse — 1 page double-spaced or 1/2 – 2/3 page single-spaced if you plan to include a photo — it’s also necessary to present yourself as fascinating.

In other words: if the agency had wanted a résumé, it would have asked you for one. Instead, it asked for bio.

Contrary to popular opinion, when an agency’s guidelines or an agent who has already received a query asks for an author bio, they’re not asking to be bored to death. Nor are they asking for a tombstone-like deadpan list of a writer’s achievements — just the facts, ma’am, and make sure not to mention anything that might conceivably surprise the reader the least little bit.

I can certainly understand where so many aspiring writers picked up the idea that they should just be producing résumés in paragraph form, however — and so should you, if you have been taking my advice and wending your way down to your local bookstore to take a gander at what’s turning up on book jackets these days. To grab a random work from the shelf nearest my desk — no, not entirely random. To render the test more interesting, I’m going to limit all of today’s examples to literary fiction authors:

The author of nine works of fiction, Andre Dubus received the PEN/Malamud Award, the Rea Award for Excellence in short fiction, the Jean Stein Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, The Boston Globe’s first annual Lawrence L. WInship Award, and fellowships from both the Guggenheim and MacArthur foundations. Until his death in 1999, he lived in Haverhill, Massachusetts.

Now, all of the listed facts are undoubtedly true, but this biographical blurb doesn’t exactly make you want to leap out of your nice, comfy office chair and rush out to buy a copy of We Don’t Live Here Anymore, does it? And that’s genuinely a pity, because if you’re even vaguely interested in the art of the novella, that would be a pretty grand book for you to pick up. (After you read it, consider seeking out the movie version one of the better adaptations of contemporary literary fictions I’ve seen in my lifetime.)

It’s also kind of surprising, as Mssr. Dubus was by all accounts a pretty interesting guy. So, I’m told, is Paul Auster, but you’d never know it from this jacket bio:

Paul Auster was born in New Jersey in 1947. After attending Columbia University {sic} he lived in France for four years. Since 1974 {sic} he has published poems, essays, novels and translations. He lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Tell me honestly: would it even have occurred to you from that bio that the gentleman would have penned a novel opening as grabbing as the first paragraph of The Music of Chance:

For one whole year he did nothing but drive, traveling back and forth across America as he waited for the money to run out. He hadn’t expected it to go on that long, but one thing kept leading to another, and by the time Nashe understood what was happening to him, he was past the point of wanting it to end. Three days into the thirteenth month, he met up with the kid who called himself Jackpot. It was one of those random, accidental encounters that seem to materialize out of thin air — a twig that breaks off in the wind and suddenly lands at your feet. Had it occurred at any other moment, it is doubtful that Nashe would have opened his mouth. But because he had already given up, because he figured there was nothing to lose anymore, he saw the stranger as a reprieve, as a last chance to do something for himself before it was too late. And just like that, he went ahead and did it. Without the slightest tremor of fear, Nashe closed his eyes and jumped.

Now, we could quibble about whether a writer who wasn’t already established could have gotten away with including a cliché like materialize out of thin air in the first paragraph of a submission, or induced Millicent to overlook the slips into the passive voice — remember, what an author with a long-term readership can get into print and what an aspiring writer can hope will make it past Millicent are often two very different things — but I don’t think that’s why some of you have been shifting uncomfortably in your seats. Let me guess why: when you looked at those two bios, all you saw was the mention of publications and awards, right?

No wonder writing your own bio seems intimidating. With expectations like that, it must feel as though an aspiring writer would have to be published already in order to produce a bio at all.

So you should be both delighted and relieved to hear that listing professional credentials is not the point of a query or submission author bio. What is the point? To depict the writer as an interesting person well qualified to write the book s/he is marketing.

How does one pull that off, short of beginning one’s bio Penster McWriterly is a fascinating person? By showing, not telling, of course, and the use of creative detail.

Don’t believe me? Okay, let’s take a gander at a book jacket bio (hey, I’m trying to play fair by choosing examples you might actually discover in a bookstore) that does include details over and above the professional basics. Here’s the jacket bio from The Bonesetter’s Daughter:

Amy Tan is the author of The Joy Luck Club, The Kitchen God’s Wife, The Hundred Secret Senses, and two children’s books, The Moon Lady and The Chinese Siamese Cats, which will adapted as a PBS series for children. Tan was a co-producer and co-screenwriter of the film version of The Joy Luck Club, and her essays and stories have appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies. Her work has been translated into more than twenty-five languages. Tan, who has a master’s degree in linguistics from San Jose State University, has worked as a language specialist to programs serving children with developmental disabilities. She lives with her husband in San Francisco and New York.

That third sentence is the one that jumps out at you, isn’t it? Could that be because it’s both interesting and unexpected?

The bio on her website is even more eye-catching. I shan’t reproduce it in its entirety — although I do encourage you to take a peek at it, as a good example of a longer author bio than you’re likely to find on the dust jacket of a living author — but I can’t resist sharing its final paragraph:

She created the libretto for The Bonesetter’s Daughter. Ms. Tan’s other musical work for the stage is limited to serving as lead rhythm dominatrix, backup singer, and second tambourine with the literary garage band, the Rock Bottom Remainders, whose members include Stephen King, Dave Barry, and Scott Turow. In spite of their dubious talent, their yearly gigs have managed to raise over a million dollars for literacy programs.

Let’s face it: of the facts mentioned in this paragraph, only writing the opera libretto is actually a literary credential, strictly speaking. But don’t you like Ms. Tan better after having read the rest of it. And aren’t you just a tiny bit more likely to pick up The Bonesetter’s Daughter if you happen upon it in a bookstore?

Brava, Ms. Tan!

Including quirky, memorable details is very smart marketing in an author bio, even at the query or submission stage: memorable is good, and likable even better. Who wants to fall in love with an author without a face? Yet most aspiring writers are afraid to take the risk, calculating — not entirely without reason that dull and businesslike is more likely to strike Millicent as professional than memorable and unexpected.

Come closer, and I’ll let you in on a little secret: any agent worth her proverbial salt thinks about whether a prospective client might make a good interview subject. Based upon the bio blurbs shown above, which of the three authors would you expect to give the most intriguing interview?

Which is to say: professional and interesting are not mutually exclusive. Just as a well-written, interesting query letter packed with unusual specifics is more likely to captivate Millicent than a dull, just-the-facts presentation of the same literary qualifications and book project, an author bio that shows the writer to be a complex individual with whom someone might conceivably want to have a conversation tends to go over better than the typical list of publications.

Some of you are still shaking your heads. I see that I shall have to pull out the big guns and revert to my all-time favorite example of a fascinating author presented as dull.

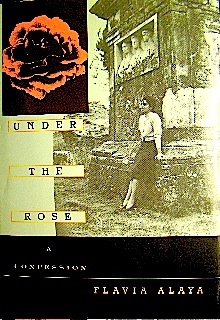

What follows is perhaps the Platonic bad author bio, the one that most effectively discourages the prospective reader from perusing what is within. And to render it an even better example for my purposes here, this peerless bio belongs to one of my all-time favorite authors, Rachel Ingalls. Her work is brilliant, magical, genuinely one-of-a-kind.

And as I have read every syllable she has ever published, I can state with confidence: never have I seen an author bio less indicative of the quality of the actual writing in a book. (Yes, dear readers, that is what writing this blog for the last four+ years has done to my psyche: discovering a specimen that might do you good, even if it disappoints me personally, now makes me cackle with glee.)

I don’t feel bad about using her bio as an example here, because I shall preface it with some awfully high praise: I think everyone on earth should rush right out and read Ingalls’ Binstead’s Safari before s/he gets a minute older. (In fact, if you want to open a new window, search for some nice independent bookstore’s website, and order it before you finish reading this, I won’t be offended at all. Feel free. I don’t mind waiting.)

But my God, her bios make her sound…well, I’ll let you see for yourself. This bio is lifted from the back of her most recent book, Times Like These:

Rachel Ingalls grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She has lived in London since 1965 and is the author of several works of fiction — most notably MRS. CALIBAN — published both in the United States and United Kingdom.

Just this, accompanied by a very frightening author photo, one that looks as though she might take a bite out of the photographer:

I have no problem with the photo — actually, I REALLY like it, because after all, this is a writer who gave the world a very beautiful story in which more than one protagonists was consumed by carnivorous toads, so a sense of menace seems downright appropriate. But have you ever seen a piece of prose less revealing of personality?

Admittedly, U.K. author bios do tend to be on the terse side, compared to their American brethren (as H.G. Wells wrote, “the aim of all British biography is to conceal”), but even so, why bother to have a bio at all, if it is not going to reveal something interesting about the author?

I have particular issues with this bio, too, because of the offhand way in which it mentions Mrs. Caliban (1983), which was named one of America’s best postwar novels by the British Book Marketing Council. Don’t you think that little tidbit was worth at least a PASSING mention in her bio?

I take this inexplicable omission rather personally, because I learned about Rachel Ingalls’ work in the first place because of the BBMC award. We’re both alumnae of the same college (which is to say: we both applied to Harvard because we had good grades, and both were admitted to Radcliffe, because we were girls, a bit of routine slight-of-hand no longer performed on applications penned by those sporting ovaries), and during my junior and senior years, I worked in the Alumnae Records office. Part of my job involved filing news clippings about alumnae. Boxes of ‘em. In the mid-1980s, the TIMES of London ran an article about the best American novels published since WWII, using the BBMC’s list as a guide.

Rachel Ingalls’ MRS. CALIBAN was on it, and the American mainstream press reaction was universal: Who?

Really, a novel about a housewife who has a torrid affair with a six-foot salamander is not VERY likely to slip your mind, is it? The fact is, at the time, her work was almost entirely unknown — and undeservedly so — on this side of the pond.

Naturally, I rushed right out and bought MRS. CALIBAN, rapidly followed by everything else I could find by this remarkable author. Stunned, I made all of my friends read her; my mother and I started vying for who could grab each new publication first. She became my standard for how to handle day-to-day life in a magical manner.

The Times story was picked up all over North America, so I ended up filing literally hundreds of clippings about it. And, I have to confess: being a novelist at heart in a position of unbearable temptation, I did read her alumnae file cover to cover. So I have it on pretty good authority that she had more than enough material for a truly stellar author bio — if not a memoir — and that was almost 20 years ago.

And yet I see, as I go through the shelf in my library devoted to housing her literary output, that she has ALWAYS had very minimal author bios. Check out the doozy on 1992’s Be My Guest:

Rachel Ingalls was brought up and educated in Massachusetts. She has lived in London since 1965.

I’ve seen passports with more information on them. But quick: can you tell me what Amy Tan does in her spare time?

You remembered, didn’t you? So which bio do you think Millicent would be more likely to recall five minutes after she read it?

But Ms. Ingalls’ value as an exemplar does not stop there. Occasionally, the travelogue motif has varied a little. Here’s a gem from a 1988 paperback edition of The Pearlkillers:

Rachel Ingalls, also the author of I SEE A LONG JOURNEY and BINSTEAD’S SAFARI, has been cited by the British Book Marketing Council as one of America’s best postwar novelists.

Better, right? But would it prepare you even vaguely for the series of four scintillating novellas within that book jacket, one about an apparently cursed Vietnam widow, one about a long-secret dorm murder, one about a failed Latin American exploratory journey turned sexual spree, and one about a recent divorcée discovering that she is the ultimate heiress of a plantation full of lobotomized near-slaves?

No: from the bio alone, anyone would expect her to write pretty mainstream stuff.

Once, some determined soul in her publisher’s marketing department seems to have wrested from her some modicum of biographical detail, for the 1990 Penguin edition of Something to Write Home About:

Rachel Ingalls grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. At the age of seventeen, she dropped out of high school and subsequently spent two years in Germany: one living with a family, the second auditing classes at the universities of Göttingen, Munich, Erlangen, and Cologne. After her return to the United States, she entered Radcliffe College, where she earned a degree in English. She has had six books published, including BINSTEAD’S SAFARI and THE PEARL KILLERS {sic}. In 1964 {sic} she moved to England, where she has been living ever since.

Now, typos aside, that’s a pretty engaging personal story, isn’t it? Doesn’t it, in fact, illustrate how a much more interesting author bio could be constructed from the same material as the information-begrudging others were?

(And doesn’t it just haunt you, after having read the other bios: why does this one say she moved to London a year earlier than the others? What is she hiding? WHAT HAPPENED DURING THAT MYSTERIOUS YEAR, RACHEL? Were you eaten by wolves — or carnivorous toads?)

I was intrigued by why this bio was so much more self-revealing than the others, so I started checking on the publication history of this book. Guess what? The original 1988 edition of this book had been released by the Harvard Common Press (located not, as the name implies, within easy walking distance of Radcliffe Alumnae records, but a couple of bus transfers away). Could it be that I was not the only fan of her writing who had gone file-diving in a desperate attempt to round out that super-terse bio?

”Talent is a kind of intelligence,” Jeffrey Eugenides tells us in Middlesex, but all too often, writers’ faith in their talent’s ability to sell itself is overblown. Good writing does not sell itself anymore; when marketing even the best writing, talent, alas, is usually not enough. Especially not in the eyes of North American agents and editors, who expect to see some evidence of personality in prospective writers’ bios.

I can only repeat: if they didn’t want the information, they wouldn’t ask for it.

Think of the bio as another marketing tool for your work. They want to know not just if you can write, but also if you would make a good interview. And, not entirely selflessly, whether you are a person they could stand to spend much time around. Because, honestly, throughout the publication process, it’s you they are going to have to keep phoning and e-mailing, not your book.

Meet ‘em halfway. Produce an interesting author bio to accompany your submissions. Because, honestly, readers like me can only push your work on everyone within shouting distance AFTER your books get published.

Speaking of which, if I have not already made myself clear: if you are even remotely interested in prose in the English language, you really should get ahold of some of Rachel Ingalls’ work immediately.

You don’t want to be the last on your block to learn how to avoid the carnivorous toads, do you?

Practical advice on how to sound fascinating follows next time, I promise. Keep up the good work!

unfortunately, writers all too often automatically assume that it’s the idea of the book being rejected, rather than a style-hampered querying letter or a limp synopsis.

unfortunately, writers all too often automatically assume that it’s the idea of the book being rejected, rather than a style-hampered querying letter or a limp synopsis.