Time for a quick poll for all of you who spent some or all of the recent holiday season hobnobbing with kith and/or kin who happened to be aspiring writers: hands up if you bumped into at least one within the last month who confided that that his new year’s resolution was — wait for it — to get those long-delayed queries out the door. Raise a hand, too, if a friendly soul astonished you by swearing that come January 1, that postponed-for-months submission was finally going to be making its way to the agent who requested it. Or that this was the year that novel was going to make its way out of that drawer and onto bookshelves everywhere.

Okay, legions with your hands in the air: keep ‘em up if you had ever heard these same writers make similar assertions before. Like, say, December of 2007, 2006, 2005, or any year before that.

I’m guessing that very few of you dropped your hands. Why on earth do we writers do this to ourselves every year?

The scourge of the New Year’s resolution, that’s why. Due to social conditioning that encourages us to believe, usually wrongly, that it’s easier to begin a new project at a time of year so energy-sapping that even the sun appears to be least interested in doing its job with any particular vim, millions of aspiring writers all across North America are going to spend the next few weeks rushing those queries into envelopes, hitting those SEND buttons, stuffing those requested materials into envelopes, and forcing themselves to sit in front of a keyboard at a particular time each day.

The predictable, inevitable, and strategically unfortunate result: for the first three weeks of January every year, agencies across the land are positively buried in paper. Which means, equally predictably, inevitably, and unfortunately, that a query or manuscript submitted right now stands a statistically higher chance of getting rejected than those submitted at other times of the year.

So again, I ask: why do writers impose New Year’s resolutions on themselves that dictate sending out queries or submissions on the first Monday of January?

Oh, I completely understand the impulse, especially for aspiring writers whose last spate of marketing was quite some time ago. Last January, for instance, after their last set of New Year’s resolutions. Just like every other kind of writing, it’s easier to maintain momentum if one is doing it on a regular basis than to ramp up again after a break.

Just ask anyone who has taken six months off from querying: keeping half a dozen permanently in circulation requires substantially less effort than starting from scratch — or starting again. Blame it on the principle of inertia. As Sir Isaac Newton pointed out so long ago, an object at rest tends to remain at rest and one in motion tends to remain in motion unless some other force acts upon it.

For an arrow flying through the air, the slowing force is gravity; for writers at holiday time, it’s often friends, relatives, and sundry other well-wishers. And throughout the rest of the year, it’s, well, life.

But you’re having trouble paying attention to my ruminations on physics, aren’t you? Your mind keeps wandering back to my earlier boldfaced pronouncement like some poor, bruised ghost compulsively revisiting the site of its last living moment. “Um, Anne?” those of you about to sneak off to the post office, stacks of queries in hand, ask with quavering voices. “About that whole more likely to be rejected thing. Mind if I ask why that might be the case? Or, to vent my feelings a trifle more adequately, mind if I scream in terror, ‘How could a caring universe do this to me?’”

An excellent question, oh nervous quaverers: why might the rejection rate tend to be higher at some times than others?

To answer that question in depth, I invite you yourself in the trodden-down heels of our old pal Millicent, the agency screener, the fortunate soul charged with both opening all of those query letters and giving a first reading to requested materials, to weed out the ones that her boss the agent will not be interested in seeing, based upon pre-set criteria. At some agencies, a submission may even need to make it past two or three Millicents before it lands on the actual agent’s desk.

We all understand why agencies employ Millicents, right? As nice as it might be for agents to cast their eyes over every query and submission personally, most simply don’t have the time. A reasonably well-respected agent might receive 1200 queries in any given week; if Millicent’s boss wants to see even 1% of the manuscripts or book proposals being queried, that’s 10 partial or full manuscripts requested per week.

Of those, perhaps one or two will make it to the agent. Why so few? Well, even very high-volume agencies don’t add all that many clients in any given year — particularly in times like these, when book sales are, to put it generously, slow. Since that reasonably well-respected agent will by definition already be representing clients — that’s how one garners respect in her biz, right? — she may be looking to pick up only 3 or 4 clients this year.

Take nice, deep breaths, sugar. That dizzy feeling will pass before you know it.

Given the length of those odds, how likely is any given submission to make it? You do the math: 10 submissions per week x 52 weeks per year = 520 manuscripts. If the agent asks to see even the first 50 pages of each, that’s 26,000 pages of text. That’s a lot of reading — and that’s not even counting the tens of thousands of pages of queries they need to process as well, all long before the agent makes a penny off any of them, manuscripts from current clients, and everything an agent needs to read to keep up with what’s selling these days.

See where a Millicent might come in handy to screen some of those pages for you? Or all of your queries?

Millicent, then, has a rather different job than most submitters assume: she is charged with weeding out as many of those queries and submissions as possible, rather than (as the vast majority of aspiring writers assume) glancing over each and saying, “Oh, the writing here’s pretty good. Let’s represent this.” Since her desk is perpetually covered with queries and submissions, the more quickly she can decide which may be excluded immediately, the more time she may devote to those that deserve a close reading, right?

You can feel the bad news coming, right?

Given the imperative to plow through them all with dispatch, is it a wonder that over time, she might develop some knee-jerk responses to certain very common problems that plague many a page 1? Or that she would gain a sense — or even be handed a list — of her boss’ pet peeves, so she may reject manuscripts that contain them right off the bat?

You don’t need to answer those questions, of course. They were rhetorical.

Now, the volume of queries and submissions conducive to this attitude arrive in a normal week. However, as long-term habitués of this blog are already no doubt already aware, certain times of the year see heavier volumes of both queries and submissions of long-requested materials than others.

Far and away the most popular of all: just after New Year’s Day.

Why, I was just talking about that, wasn’t I? That’s not entirely coincidental: this year, like every year, Millicent’s desk will be piled to the top of her cubicle walls with new mail for weeks, and her e-mail inbox will refill itself constantly like some mythical horn of plenty because — feel free to sing along at home — a hefty proportion of the aspiring writers of the English-speaking world have stared into mirrors on New Year’s eve and declared, “This year, I’m going to send out ten queries a week!” and/or “I’m going to get those materials that agent requested last July mailed on January 2!”

While naturally, I have nothing against these quite laudable goals — although ten queries per week would be hard to maintain for many weeks on end, if an aspiring writer were targeting only agents who represented his type of book — place yourself once again in Millicent’s loafers. If you walked into work, possibly a bit late and clutching a latte because it’s a cold morning, and found 700 queries instead of the usual 200, or 50 submissions rather than the usual 5, would you be more likely to implement those knee-jerk rejection criteria or less?

Uh-huh. Our Millicent’s readings tend to be just a touch crankier than usual right about now. Do you really want to be one of the mob testing her patience?

This is the primary reason, in case I had not made it clear enough over the last couple of months, that I annually and strenuously urge my readers NOT to query or submit during the first few weeks of any given year. Let Millie dig her way out from under that mountain of papers before she reads yours; she’ll be in a better mood.

How long is it advisable to wait? Well, in previous years, I have suggested holding off on sending anything to a North American agency for a full three weeks. I did not select that length of time arbitrarily: the average New Year’s resolution lasts three weeks, so the queries and submissions tend to drop off around then. Conveniently enough, US citizens get a long weekend at that point in January, the Martin Luther King, Jr., holiday, to start stamping those SASEs.

This year, I am not recommending holding off for three weeks. In 2010, I am urging every writer within the sound of my voice to hold off for six.

No, in answer to that question 33% of my readers just shouted indignantly at my screen, I have not taken leave of my senses, thank you; I am merely trying to help you maximize your query or submission’s chances of success. I have my fingers crossed, hoping madly that by mid-February — say, just after Valentine’s Day, a holiday few aspiring writers are likely to commemorate by sending roses or chocolates to Millicent, anyway — Millie, her boss the agent, her agent’s boss who owns the agency, the editors to whom the agent habitually pitches, and those editors’ bosses will have finished freaking out at the stunning news that for the first time, e-books outsold hard copies at Amazon on Christmas.

Okay, so those sales figures were just on Christmas Day itself, an occasion when, correct me if I’m wrong, folks who had just received a Kindle as a present might be slightly more likely to download books than, say, the day before. But that’s not what the headlines screamed the next day, was it? I assure you, every agency and publishing house employee in North America has spent the intervening days fending off kith and kin helpfully showing him articles mournfully declaring that the physical book is on the endangered species list. Or ought to be.

Once again, I invite you to step into Millicent’s ballet flats. She’s been hearing such dismal prognostications as often as the rest of us while she’s been off work for the past week or two. When she steps across the agency threshold on Monday, too-hot latte clutched in her bemittened hand, the Millicent in the cubicle next to hers will be complaining about how his (hey, Millicents come in both sexes) kith and kin has been cheerfully informing him that he will be out of a job soon. So will half the people who work in the agency — including, as likely as not, Millicent’s boss.

It’s only reasonable to expect, of course, that through the magic of group hypnosis, the more everyone repeats it, the more of a threat the Kindle news will seem; the scarier the threat, the more dire the predictions of the future of publishing will become. By lunchtime, half the office will be surreptitiously working on its resumes.

Given the ambient mood in the office, do you really want yours to be the first query she reads Monday morning? Or the fiftieth? Or would you rather that your precious book concept or manuscript didn’t fall beneath her critical eye until after everyone’s had a chance to calm down?

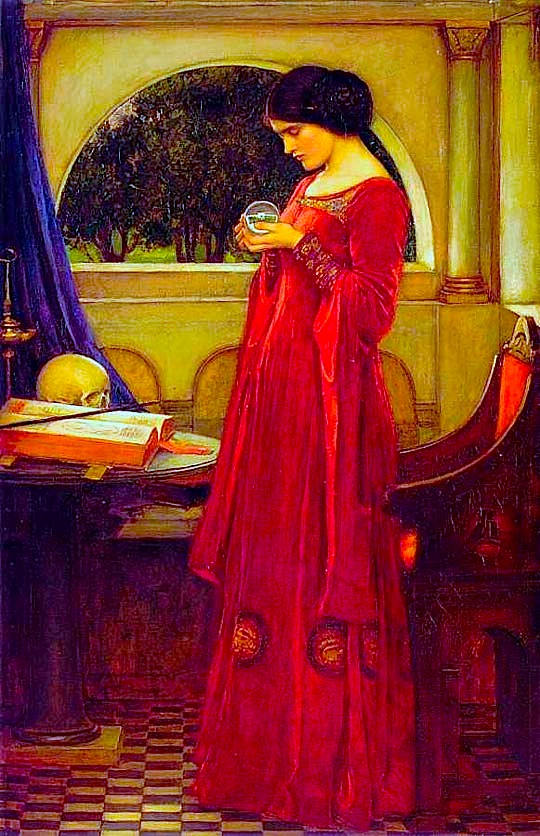

Quick disclaimer: six weeks may well not be long enough for this particular shock to pass. I am not a necromancer of any stripe; please don’t imagine that I am typing this with one hand and clutching a crystal ball with the other. I picked six weeks because, by law, US-based agencies must issue tax documentation on royalties by the end of January. Might as well wait until the stressed people have one less reason to be stressed, right?

Will another two weeks honestly make any difference? Again, I don’t have a crystal ball — but by then, those of you who each year stubbornly reject my annual admonition to eschew writing-related New Year’s resolutions will have had a nice, long chunk of time to see if you could, say, up your writing time by an extra hour per week. Or per day. Or prepared a contest entry for that literary contest you’d always meant to enter.

Far be it from me to discourage keeping that kind of resolution, whether you choose to put it into action on New Year’s Day, the fourth of July, or St. Swithin’s day. Only please, for your own sake, don’t set the bar so high that you end up abandoning it within just a couple of weeks.

If you must resolve, resolve to set an achievable goal, one that you can pull off without wearing yourself out quickly. In the long term, asking yourself to write two extra hours per week is more likely to become a habit than eight or ten; committing to sending out one query per week is much easier than twenty. Heck, if Millicent resolved to get through those masses of queries and submissions currently completely concealing her desk from the human eye, she’d fling her latte in disgust within the first hour. Steady, consistent application is the way to plow through an overwhelming-seeming task.

Okay, if I’m sounding like Aesop, it’s definitely time to sign off for the night.

Except to say: because so many aspiring writers will be acting on their (sigh) New Year’s resolutions, and thus may be relied upon to be surfing the net rabidly for sensible guidance, I’m going to take a break from self-editing issues for the next couple of weeks to deal with the absolute basics that every writer needs to know. What a query is, for instance, and why a novelist typically needs an agent. Why generic queries seldom work. How to format a manuscript.

You know, the kind of things folks in the publishing industry assume that talented writers already know. Presumably because the muses showed up next to each of our cradles and gave us the knowledge at birth. Just in case the muses are thirty or forty years behind schedule, I’m going to start filling in the gaps with Monday’s post.

Please keep those craft and revision questions, coming, though — I’m far from done talking about how to get the best out of a manuscript. Just let me get all of these New Year’s resolutions out of the way first.

As always, keep up the good work!

As this is not the best time for querying or submitting, why not use it to edit, revise, or rewrite? That way, once the gods of writerly submission are smiling again, one can put an even bigger smile on their collective faces by sending truly great examples of writing craft.

Dave

P. S. That’s what I’m doing!

Good for you, Dave! That’s what I’m hoping smart writers everywhere will do…

Hi there!

I just came across an article I thought might make you feel a bit better:

http://news.cnet.com/8301-1023_3-10422538-93.html?part=rss&subj=news&tag=2547-1_3-0-20

Might be wishful-thinking, but still…

Oh, that’s fascinating, Nuria. I’d noticed that other commenters had noted the Christmas Day/Christmas present correlations, but that article brings up some other interesting ways to look at Amazon’s assertion.

Let’s hope that the fine folks who make acquisition decisions were listening!

Well, I queried BEFORE Christmas to an agency that said it replies in 6-8 weeks, so hopefully that won’t kill me. I have work to do anyway, so if it takes until February or March to get an answer back, I’ll be too busy to angst over it!

As far as Kindle is concerned, until you can read it in the bathtub or the pool, I’m not getting one. A $400 “Oops” is too rich for my blood.

Whew – feeling much better about my mid-Feb start date! I also never submit anything important over the weekend or on Monday or Friday. Tues-Thurs is the sweet spot.

Not submitting on a Friday or over the weekend is clever, Lucy — that way, your missive doesn’t end up in Millicent’s oh-my-God-it’s-Monday pile.

Most agencies are pretty good about going through queries in more or less the order they were received. But I think you’d be wise to tack a month or so onto their stated turn-around time, just for sanity’s sake.

And here’s to keeping good writers unelectrocuted!

Anne I got a problem. I recently discovered that my main character has the same name as a celebrity. Let’s not get into how it happened the important issue is what to do next. What should I do? Does it matter that the names aren’t spelled the same? You’re going to tell me I have to change the name aren’t you?

What an interesting problem, Scott; I don’t know any writer who checks the SAG or Equity listings before naming a character. Changing the name would be the most direct way to solve the problem — but are you positive that is is actually a problem that needs solving?

Does your protagonist share both the first and last name with the celebrity? If it’s only one of the proper names is the same (even if that name is, say, Cher), you wouldn’t necessarily need to alter it. In fact, if the celebrity has been around for awhile, you could boldly admit that you’re aware of the similarity by having another character comment on it to the protagonist A simple “Yeah, my parents just adored Buddy Holly,” from a character named either Buddy or Holly might actually make for some good characterization.

You could pull off the same trick, potentially, even if both names were the same, provided that the celebrity is one from quite some time ago — which I’m guessing is the case, since you’ve only just recognized the similarity. If I saw a protagonist named Thomas Edison, Orville Wright, or Ida Lupino in a novel set today, I would tend to conclude that Mr. and Mrs. Edison, Wright, and Lupino just couldn’t resist being copycats when handed the birth certificate forms.

In general, if it’s not a celebrity that currently gets much attention you may not need to worry about readers making the connection, or at least being distracted by it, as long as the narrative acknowledges the similarity. It’s not as though it is possible to trademark a name. While you might want to have a chat with a lawyer who specializes in publishing to learn the rather complex rules, in a work of fiction (and we are talking about a novel here, right?), a character usually has to be either VERY similar to the real-life name holder or VERY different (to the point of libel) before anyone concerned even wants to kick up a fuss.

The far more likely result: Millicent might assume that the name choice was deliberate, and that you want the reader to make the association. That may be unfair if the protagonist and the celebrity share a common name — there are quite a few Will Smiths and Mohammed Alis, after all. If protagonist Beyoncé is a singer or dancer, though, Millie may well see that as authorial shorthand. Not worth the risk.

Of course, she may assume that if the names are merely similar — which would be the other relatively easy way to fix the problem. Do what new SAG members do: add a middle name. (Mary Tyler Moore and Mary Moore are not the same person, right?) Or change the spelling: Audree-Lou Hepburn definitely doesn’t scan the same way that Audrey Hepburn does.

If you’re very resistant to altering the name — and I’m sensing that you are, given how you phrased the question — you might want to give some serious thought about why. Is there something about the name that is essential to conveying who the character is? Could a name that’s close approximate that element? Or are you just frustrated because changing a character’s name is a lot of work?

Do let me know if I’ve gone wide of the mark here — there are so many possible permutations of this problem that it’s entirely possible that I haven’t addressed your specific situation. This would make a good subject for a blog post, anyway.

Anne thank you so much for taking the time to answer my question. And so fast too! The main character in my novel shares her first and last name with the celebrity(still on tv). My character is nothing like the celebrity. I did not want to change the name at least not the last name because it is relative to the life of the character. I guess the real problem is once I start submitting my novel I may never know if the rejections are based on this issue, or if it’s just my terrible grammar. Next question. My novel is written from first person POV. Is it a good idea for the synopsis to be in first person POV?

That makes perfect sense, Scott. My advice would be to alter the first name for submission purposes, to rule it out as a rejection reason; you can always change it back prior to publication. Then talk to your agent about it after you sign the representation contract. The agent would be able to tell you whether it will be problematic at the submitting to editors stage.

A fiction synopsis should be in the third person and the present tense. The only time a synopsis should be in the first person is if it’s for a memoir. I’ve discussed this at great length in the HOW TO WRITE A REALLY GOOD SYNOPSIS series, though; you might want to check out the category on the archive list at the lower right-hand side of this page.