My apologies for the must-have-been-agonizing delay between the prize posts for the first-place winners of the Author! Author! Great First Page Made Even Better Contest and the second-place winners. Believe me, the lapse was not intended to be editorial: I’m excited about both of today’s winners, but I had a bit of a car-crash recovery setback earlier in the week. I didn’t want to risk sounding grumpy about two writers whose narrative voices I like quite a bit.

So a drum roll, please, for the joint winners of second prize in Category II: Adult Fiction: David A. McChesney’s SAILING DANGEROUS WATERS and Ellen Bradford’s PITH AND VINEGAR.

While all of that portentous rumbling is still hanging in the air, let me take a moment to air one of my pet peeves: gratuitous quotation marks. The other day, a staffer at my physical therapist’s office handed me a special-ordered piece of medical equipment in this bag:

What, one wonders, was the writer’s intent in placing quotation marks around my name? Was he in some doubt about whether it was my real name — as in, This belongs to the so-called Anne Mini? Did he mistakenly believe that he was shipping this not particularly personal piece of equipment not to my PT, but to a monogrammer, and he wanted to make sure the right spelling stitched into it? Or had someone immediately behind him just shouted my name, and he was quoting her?

Was this merely a case of forgotten attribution? Is this an obscure quote from a book I do not know — a minor work of Charles Dickens, perhaps? Or, still more disturbingly, is this kind soul trying to let me know, albeit in code, that somebody out there is talking about me?

None of the above, probably: my guess would be that the guy with the marking pen thought, along with a surprisingly high percentage of the marking-things population, that quotation marks mean the same thing as underlining. He is mistaken.

Don’t ever follow his example. To a professional reader, the common practice of placing things in quotation marks to indicate either emphasis in speech (“Marvin K. Mooney, will you ‘please go’ now?”), a stock phrase (everybody laughed, because “all the world loves a lover”), or just to call attention to individual words on a sign (Fresh “on the vine” tomatoes, 3 for $2) simply looks illiterate. Sorry to be the one to break the harsh news, but it’s true.

So how should one use quotation marks? How about reserving them for framing things that characters actually say?

I know; radical. The next thing you know, I’ll be calling for aspiring writers to use semicolons correctly.

I do not bring any of this up lightly — or, indeed, purely to rid the world of a few more sets of perplexingly-applied quotation marks. Both of today’s entries grabbed the judges with their strong, distinct authorial voices, but each left us murmuring amongst themselves, speculating about what the writer’s motivations might have been.

Although these two first pages don’t actually have a great deal else in common — other than both beginning the text 1/4 of the way down the page, rather than 1/3; the addition of a single additional double-spaced line would have made a positive cosmetic difference in both — the judges agreed that they shared a certain kinship: the unanswered question might well lead even an agency screener who admired the writing to hesitate about reading on.

Why? Well, Millicent isn’t all that fond of unanswered questions on page 1, and with good reason: in order to be able to recommend a novel manuscript to her boss, she is going to have to be able to tell him (a) who the protagonist is, (b) what the book is about, (c) the book category, (d) to what specific target audience within that book category’s already-established readership it should be marketed, and (e) how this book is different/better than what is already on the market for the folks mentioned in (e).

If Millicent can’t answer any of these questions. she’s going to have a hard time convincing the agent even to read the submission. (Actually, she prefers to be able to answer all of them by the bottom of p. 1, but she’s prepared to change her mind between then and p. 50.) And no, “But the writing is so good!” is no substitute for being able to come up with answers: books are pitched to editors within well-established categories.

So when a fresh, new narrative voice that does not appear to fit comfortably within an existing book category, our Millie is left in something of a quandary. How, she wonders, is she going to make the case for this book?

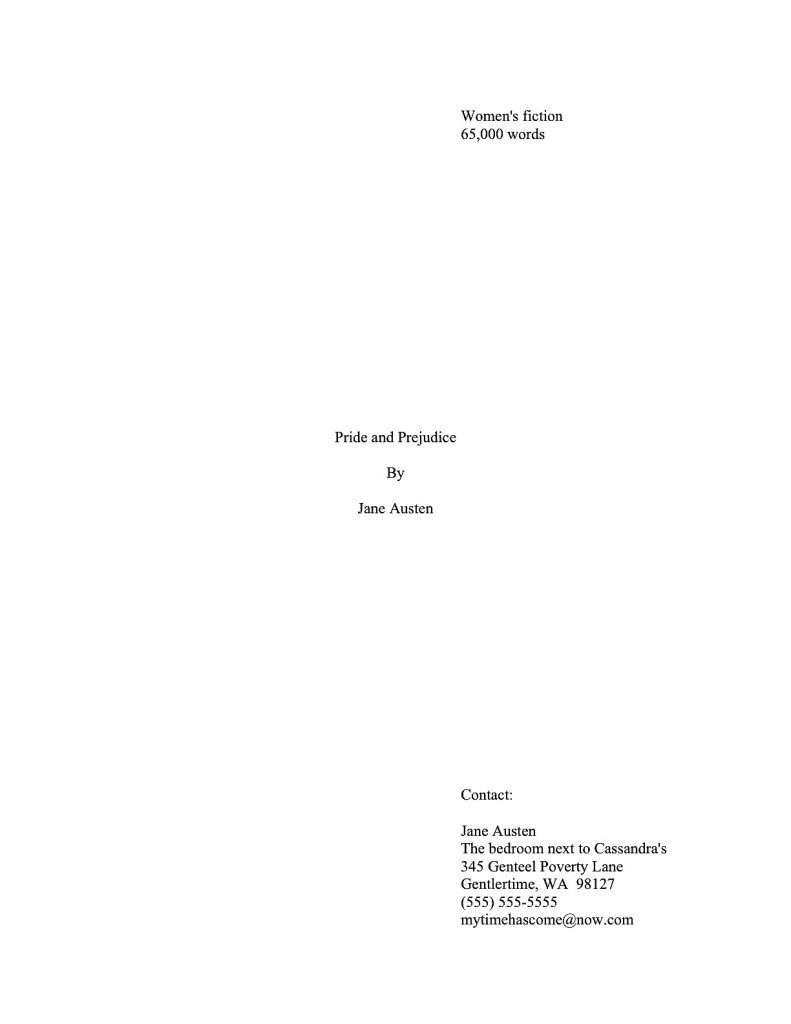

That’s a good exercise to apply to any manuscript, incidentally: reading a first page or book description and trying to figure out the book’s category is excellent practice for narrowing down your own. In that spirit, take a gander at Dave McChesney’s first page and book description; tell me, what do you think the category is?

If you found yourself murmuring, “Hmm, this reads like Naval Adventure,” you agree with most of the judges. Even more so if you additionally told yourself, “I’d bet a doubloon that there’s adventure awaiting those characters within the next page or two.” Although some of the judges felt that it might have been more of a Millicent-grabber to toss the characters straight into that imminent action, none denied that page 1 set up the expectation for excitement.

Cast your eyes over the book’s description, though, and see if you think the proverbial shoe still fits the assumed book category:

Still sounds like a rollicking Naval Adventure, doesn’t it? Or do I sense some puzzled head-scratching out there?

“Wait just a doggone minute, Anne,” head-scratchers across the English-speaking world protest. “He hopes to quickly set out for his world, England, and Evangeline, but finds obstacles continually placed in his path? In the known world? Does this take place in a different world, or this one? And if it’s the former, shouldn’t that be made clear to Millicent on page 1?”

Well caught, head-scratchers — and in answer to that last question, a resounding yes. Let’s take a gander at how Dave himself categorizes his book:

SAILING DANGEROUS WATERS, the second Stone Island Sea Story, combines Naval Adventure and Fantasy. An additional yet similar world gives these voyagers of the early nineteenth century more seas to sail and challenges to meet. Uniquely, they are aware of and able to control their journeys between the two worlds.

An interesting notion, right? But you can already hear Millicent slapping her forehead and muttering, “How on earth am I going to define this book for my boss?”

Universally, the judges felt that in fairness to Millicent, some fantasy elements should appear on page 1. Otherwise, they argued, it was simply too likely that when she came upon fantastic happenings later in the manuscript, she might conclude — wrongly in this case — that Dave did not know that he was genre-jumping, or that the authorial choice to present a fantasy premise in a completely dedicated naval fantasy voice was in fact a choice, not a misunderstanding of how book categories work.

That’s why Dave’s taking the quite large risk of telling Millicent in his brief book description (and presumably in his query) that this is a category-crosser is quite smart. True, there is not a great deal of demonstrable overlap between the readership of these two categories. (Which is why I am bound to mention marketing advice agreed-upon by a full half of the judges: since this is such a strong Naval Adventure voice, why not write a straight Naval Adventure first, land an agent that way, and then segue into fantasy with the NEXT book?) Also, if an agency is not open to the possibility of combining these two disparate categories in a single book — or, in this case, a series — its Millicent may well reject the query on that basis alone.

So why is it smart to give her the opportunity up front? Because for a truly genre-expanding novel to make it into print, it’s going to need an agent willing — nay, eager — to take on the challenge. Trust me, it’s far, far easier on a writer emotionally to find out a particular agent is not up for it at the querying stage, rather than several years into an unhappy writer-agent relationship.

Let’s assume for the moment that Dave’s query has already passed muster with the Millicent guarding an agency very much up for this challenge. How might Millie respond to this first page?

As you may see (and we have continually seen throughout this series), how a professional reader responds to a page of text can be extraordinarily different from how an ordinary reader might. I would be surprised, for instance, if many of you had caught the verb repetition in lines 1 and 2, or the lack of a necessary paragraph break on line 8. (It’s a bit confusing to have one person speak and another — or in this case, several others — act within the same paragraph.) Or, really, to be actively annoyed by the almost universal Baby Boomer tendency to compress the phrase all right into alright.

I blame album cover lyrics for the ubiquity of that last one. (If you don’t know what album covers are, children, ask your grandparents.)

Nor would the average reader be likely to gnash her teeth over the preponderance of tag lines, those pesky he said, he mentioned, he groaned speaker-identifiers, but Millicent’s choppers are unlikely to remain ungnashed. Why? Well, one of the standard measures of the reading level of the target audience is the frequency with which tag lines appear: in books for early readers, for instance, who may well be reading aloud or having the book read to them, tag lines are virtually universal.

“See Spot run, Dick,” Jane said.

“I see Spot run,” Dick replied. “Run, Spot, run.”

In most adult fiction, on the other hand, tag lines are deliberately minimized. Although the frequency with which they are expected to appear does vary from book category to book category (chant it with me, campers: there is no substitute for reading widely in your chosen book category, to learn its norms), most of the time, it’s simply assumed that the reader will be able to figure out that the words within quotation marks are in fact being spoken aloud by a character without the narrative’s having to stop short to tell us so.

After all, quotation marks around words can only mean that either those words were spoken out loud or the narrative is trying to cast doubt upon the authenticity of something (as in “I see you’re wearing your ‘designer’ dress’ again, Alice.”), right?

Typically, tag line minimization is achieved by incorporating other action or thought into a dialogue paragraph — or simply to alternate between already-established speakers. Like so:

“Oh, there’s Spot at last.” Jane blew on her freshly-filed nails to free them from dust before she applied screaming red polish. “And there he goes. See Spot run, Dick.”

Dick backed against the wood-paneled wall, eyes wide. “I see Spot run. Run, Spot, run!”

Jane lowered one heavily-lashed lid, the better to aim her gun. “How would you feel about following Spot’s example, Dick?”

“Pretty darned good.”

“Then run, Dick, run, before I change my mind and turn you into Swiss cheese.”

These are all easily-fixed matters of style, however. There was one obviously deliberate authorial choice, however, that left the judges scratching their heads as if they had wandered into a dandruff convention. Millicent almost certainly would have the same reaction. Any guesses as to what on this page might engender that response?

If you flung your hand into the air, shouting, “Oh, I’ve been scratching my head raw over this one, too! Why are Original Vespican, Original, Baltican all in italics? They aren’t foreign words, are they, or the names of ships, which could legitimately be italicized?”

Apparently not — from how they are used here, they may be the names of nationalities or tribes. If that’s the case, however, it’s hard to guess what the authorial point of italicizing them could possibly be: one does not, after all, routinely employ italics when talking about Swedish fjords or Navaho rugs.

Presumably, there is a perfectly sound rationale behind this authorial choice — Dave’s been an active member of the Author! Author! community for years, and never have I known him to set at naught the rules of standard format for frivolous reasons. I said as much to the other judges, in fact. But they felt — and I must say I concur — that however valid it might be to include those italics in the published version of the book, at the submission stage, the manuscript should omit them.

Why? Well, as we all know (at least I hope we do), manuscripts do not resemble published books in many important respects. Double-spacing, for instance, and doubling dashes. While it might conceivably be possible for a writer to justify an occasional deviation from standard format, remember, the submitter is literally never there when Millicent screens his manuscript; it is going to need to stand on its own merits. And Millicent is not all that keen on formatting originality: she knows all too well that any fancy formatting in the published book would be the editor’s call, not the author’s.

In Dave’s case, then, it could certainly be argued that no one but his future editor is genuinely qualified to determine whether those italics should remain or not. However, that perfectly legitimate point is not likely to help him much at submission time, if Millicent gets tired of scratching her head over it.

So I offer up this question for your pondering pleasure: since Millicent’s delicate eyebrows are so very likely to be lifted beyond the point of comfort by those page 1 italics, wouldn’t it be more prudent for Dave to hold off on those italics-by-choice until he can discuss it with his future editor? That way, the risk of the italics triggering rejection drops to zero, and he can still make a case for including those italics in the eventual book.

Isn’t it amazing how much issues ostensibly unrelated to either the quality of the writing, the strength and consistency of the narrative voice, or even the inherent excitement of the story can affect its submission chances?

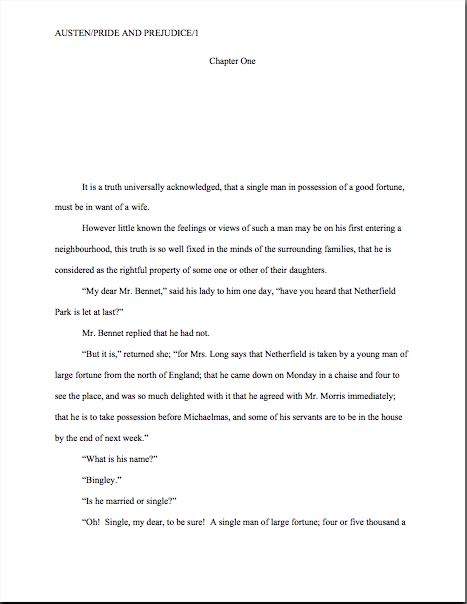

With that capacious question ringing in our ears, let’s turn to Ellen Bradford’s extremely likable page 1:

Engaging, isn’t it? I must say, this one won me over in spite of myself: as a professional reader, I tend to be a trifle suspicious of self-deprecating narrators; it’s hard to keep it up for the entire length of a book. It’s even harder to do if the narrative is genuinely funny, as this page is — self-deprecating humor often lends itself to one-note storytelling, and even when it doesn’t, those who do not get the jokes are wont to write off the narrator as whiny.

Hey, I don’t control readers’ reactions. I just tell you about ‘em.

This is a voice that a lot of readers would quite happily follow for chapters on end — but is it compelling enough to carry Millicent on to page 2?

That’s not at all a frivolous question, or even a reflection upon the writing here: let’s face it, Millicent doesn’t make it to page 2 in most submissions. And contrary to popular opinion amongst aspiring writers, the quality of the writing is not always the determinant of whether she flips the page.

Remember, our Millie likes to be able to answer the basic questions about a submission in at least a cursory way by the bottom of page 1. To recap: (a) who the protagonist is, (b) what the book is about, (c) the book category, (d) to what specific target audience within that book category’s already-established readership it should be marketed, and (e) how this book is different/better than what is already on the market for the folks mentioned in (e).

Take another gander at Ellen’s page 1. How many of those questions would you be comfortable answering?

Oh, it establishes the protagonist and the tone of the book beautifully; one could even make a pretty good guess that the target market is women insecure about their appearance — which is to say pretty much all of us. But what is this book about? Where would it sit on a shelf in Barnes & Noble?

Because the judges were all about book category-appropriateness, the contest’s rules asked entrants to provide a brief paragraph dealing with questions (b) – (e). Here’s Ellen’s response:

Pith and Vinegar will turn the world of adult fiction on its ear. Or its kidney. Take your pick. But what remains non-negotiable and absolutely, undeniably 100 percent pure fact is that adult fiction will be resting on an unfamiliar body part.

As will the story’s heroine.

Again: funny, even charming. But did it answer those professional questions, beyond alerting us that it is fiction aimed at adults?

Is it Mainstream Fiction? Women’s Fiction? Chick lit? The judges were inclined toward the latter, but let’s take a peek at the longer book description, to see if we can find out more.

Okay, so the book sounds like a hoot; I give you that. And now we know that it is Women’s Fiction — which is fabulous, as this is a voice that would appeal to many, many readers in that target market. There is surprisingly little funny fiction out there right now featuring larger female protagonists, so you go, Ellen!

But this description would be at a very serious competitive disadvantage at most US-based agencies. Care to guess why?

If you already had your hand in the air, crying out, “But Anne, those paragraphs are not indented, and she skipped a line between paragraphs!” give yourself a hearty pat on the back. You are quite right: in dealing with the publishing industry, every paragraph should be indented. Block-formatting just looks illiterate to Millicent.

You wouldn’t want her to think you were the kind of person who would shove quotation marks around perfectly innocent words and phrases for no apparent reason, would you?

No, but seriously, folks, this is a trap into which well-meaning aspiring writers inadvertently stumble all the time. An agency’s submission guidelines ask for an unusual addition to the query packet, or the form-letter positive response to a query requests a much shorter synopsis than the writer has on hand. So he tosses something off — only to realize with horror a few days after he sent it that those additional requested materials were not in standard manuscript format.

If that doesn’t seem like a big deal to you, think of it this way: which would you prefer, Millicent’s starting to read your synopsis with an open mind, or her harrumphing at the first sight of it, “Oh, no — I wonder if the manuscript is improperly formatted, too,” and beginning to peruse your word with a pre-jaundiced mind?

There’s another common generator of Millicent’s knee jerks back on page 1. Let’s take a gander:

A couple of those points caught you by surprise, didn’t they? Almost universally, Millicents are a mite touchy about having jokes explained to them, at least on the page. After the tenth time it happens in a single day of screening, it can start to feel like a minor insult to one’s intelligence.

And there’s some justification to that: the writerly impulse to over-explain has does typically have its roots in a fear that the average reader won’t get it. Much of the time, those fears are unfounded; inveterate readers are a pretty savvy bunch, and professional readers even more so.

Here, those fears are definitely unjustified — it would be perfectly easy to follow the metaphor without, say, the narrative’s informing us three times that it is indeed a metaphor, or repeating the word potato every few lines. With an image that strong, it’s a safe bet that the reader is going to remember it.

Yet our amusing narrator seems far more afraid that the reader’s mind will stray off the relevant spud than to let us know where the story is set, how the narrator fits into the world she is depicting (perhaps she works at the Bloodworthy News?), or even the time frame — because, let’s face it, a lot of women have felt potato-shaped across a broad array of contexts for at least the last century. (They might well have felt that way before, but bathroom scales were not widely available until the 1920s, so they didn’t have numbers to back up the general impression.)

Are you seeing a running theme here, though? Both of these winning entries left Millicent guessing about a few significant matters at the bottom of page 1 — and in both cases, one of those significant somethings was the book category.

But that’s actually not the primary reason that a well-trained Millicent might not turn the page. Any guesses?

Hint: the problem I have in mind is noted twice on the marked-up example above.

Yes, that’s right: the single-sentence paragraphs. Aspiring writers just love these, and as we’ve discussed, they can work well in moderation — to introduce a bit of genuinely startling information or a plot twist that might get lost to the skimming eye if the sentence were attached to the paragraph above or below.

The vast majority of the time, that’s not how such one-line paragraphs turn up in manuscript submissions, however. A surprisingly high percentage of writers who aspire to be funny seem to believe that a single-line paragraph is the only way to designate a punch line, a tactic about as subtle as following Millicent around with a drum kit and executing a rim shot each and every time she reads a joke.

Think about it: if the reader can see from across the room that a joke is coming, because every joke that preceded it in the text was also in a single-sentence paragraph, hasn’t the narration lost the element of surprise so crucial to maintaining a humorous tone all the way through the book?

That doesn’t appear to have been Ellen’s motivation in creating the single-sentence paragraphs here, though; my guess is that they are intended to reflect the greater-than-full-stop pause these statements might carry in verbal speech. Regardless, breaking the it takes at least two sentences to form a narrative paragraph rule doesn’t actually provide any benefit to the narrative — certainly not a large enough bang to outweigh the risk of a very well-read Millicent’s knee jerking over it.

Don’t believe me? Okay, here are the opening three sentences as submitted:

If eyes were the windows to the soul, I was a potato.

Well, metaphorically speaking, I was a potato. Physically, I didn’t look like a root vegetable unless I turned sideways in one of those nasty change-room mirrors that sadistic shops selling Barbie-sized clothing always mounted on their flimsy doors.

Got those firmly in mind? Now cast your eyes over them with the single-sentence paragraph problem removed in the most obvious manner imaginable — although while I’m at it, I’ll do a spot of trimming.

If eyes were the windows to the soul, I was a potato. Well, metaphorically speaking. Physically, I didn’t look like a root vegetable unless I turned sideways in one of those nasty change-room mirrors that sadistic shops selling Barbie-sized clothing always mounted on their flimsy doors.

Was any meaning lost in that transition? Any nuance, even? Is there anything to prevent someone reading it out loud from emphasizing that first sentence?

Of course not. The same holds true for the other single-sentence paragraph. Let’s review it in context:

A few stray hairs perhaps, under harsh fluorescent lighting, but everyone knew how cruel those lights could be.

All right.

I may in some tiny and insignificant way, have resembled a potato. But some potatoes on eBay looked like the Virgin Mary or Albert Einstein, so there was a lot of genetic variance. And metaphorically speaking, I was covered with many eyes, like a potato.

And here it is again, cleaned up a trifle:

A few stray hairs, perhaps, under harsh fluorescent lighting, but everyone knew how cruel those lights could be.

All right, I may, in some tiny and insignificant way, resemble a potato. But some potatoes on eBay looked like the Virgin Mary or Albert Einstein, so there was a lot of genetic variance. And metaphorically speaking, I was covered with many eyes.

Okay, so that was more than a trifle, but you know how I (and Millicent) feel about word repetition and comma use. My point is — and you probably saw this coming, right? — that stand-alone paragraph wasn’t actually adding anything significant to the text. The next paragraph was able to absorb it into its first sentence with no loss of meaning at all.

What lesson are we to derive from all of this? Several, actually. First, I clearly was eager to jump back into the swim of commenting on these entries — this is a long post, even by my standards. Second, while it may require a bit of plot massage, the more you can show Millicent of the book’s tone, what it’s about, who the protagonist is, and so forth by the bottom of page 1, the happier she will be.

Finally, as we’ve been seeing throughout this series, even a very well-honed narrative can often benefit from a bit of judicious revision. Just to stick that bug in the ear of all of you who are going to receive requests for pages in the months to come: fight the urge to send off those pages instantly; it’s well worth your time to re-read those pages IN THEIR ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD before popping ‘em in the mail or hitting SEND.

Do I need to remind you about Millicent’s jumpy knee? Don’t make me pull out another quotation mark example to get her going.

A few more contest entries to come, then it’s on to Synopsispalooza, beginning on Saturday. Well done, Ellen and Dave, and keep up the good work!

No matter how many pages or extra materials you were asked to send, do remember to read your submission packet IN ITS ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD before you seal that envelope. Lest we forget, everything you send to an agency is a writing sample: impeccable grammar, punctuation, and printing, please.

No matter how many pages or extra materials you were asked to send, do remember to read your submission packet IN ITS ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD before you seal that envelope. Lest we forget, everything you send to an agency is a writing sample: impeccable grammar, punctuation, and printing, please.