Aspiring writer on the job, making the world safe from Hollywood Narration

Hello again, campers —

I’m hoping to get back to generating brand-new posts sometime next week; the hand doc turned pale at hearing how often and how much I usually post, but I entertain high hopes of his getting over the shock soon. In the meantime, I am re-running some older posts on constructing effective interview scenes, to keep those revision gears chugging in everybody’s brains. Just so those of you who read it the first time around won’t be too bored, I reserve the right to interpolate comments or make small changes from time to time — or, in this case, add huge, honking sub-sections — but for the most part, I shall be husbanding by hand strength by posting these pretty much as is.

Before anyone decides the result is unlikely to be relevant to the types of manuscript revision we have been discussing, the interview scene is one of the most frequently-muffed types of dialogue; unfortunately, it’s also among the most common, period. Interview scenes, for the benefit of those of you joining us late in this conversation, are spates of dialogue where one character (usually the protagonist) is trying to extract information (the pursuit of which is often the driving force behind the plot) from another character (sometimes, but not always, historically reluctant to spill.)

In discussing interview scenes, we’ve also talked quite a bit about Hollywood narration, my term for a scene where Character 1 tells Character 2 a bit of information or backstory of which both 1 & 2 are already aware, purely so the reader may learn it. Yet Hollywood narration is not the only questionable tool writers sometimes use to shovel heaping piles of extraneous facts into a narrative.

Today, I shall discuss a few others. Enjoy!

You know how I keep saying that real life perpetually volunteers examples at just the point I could really, really use them on the blog? Well, it’s happened again: I was actually writing yesterday’s post on Hollywood Narration and how annoying a poor interviewer character can be, when the phone rang: it was a pre-recorded, computerized political opinion poll.

Now, I don’t find polls much fun to take, but since I used to do quite a bit of political writing, I know that the mere fact that the polled so often hang up on such calls can skew the accuracy of the results. Case in point: the number of percentage points by which most polls miscalled the last presidential election’s results.

So I stayed on the line, despite the graininess of the computer-generated voice, so poorly rendered that I occasionally had trouble making out even proper names. A minute or so in, the grating narrator began retailing the respective virtues and aspirations of only two candidates in a multi-player mayoral race — neither of the candidates so lauded was the current mayor, I couldn’t help but notice — asking me to evaluate the two without reference to any other candidate.

In politics, this is called a push poll: although ostensibly, its goal is to gather information from those it calls, its primary point is to convey information to them, both as advertisement and to see if responders’ answers change after being fed certain pieces of information. In this poll, for instance, the inhumanly blurred voice first inquired which of nine candidates I was planning to honor with my vote (“I haven’t made up my mind yet because the primary is a month and a half away” was not an available option, although “no opinion” was ), then heaped me with several paragraphs of information about Candidate One, a scant paragraph about Candidate Two, before asking me which of the two I intended to support.

Guess which they wanted my answer to be?

Contrary to popular opinion, although push polls are usually used to disseminate harmful information about an opponent (through cleverly-constructed questions like, “Would you be more or less likely to vote for Candidate X if you knew that he secretly belonged to a cult that regularly sacrifices goats, chickens, and the odd goldfish?”), the accuracy of the information conveyed is not the defining factor, but the fact of masking advertisement under the guise of asking questions, In a well-designed push poll, it’s hard to tell which candidates or issues are being promoted, conveying the illusion of being even-handed, to preserve the impression of being an impartial poll.

Yesterday’s call, however, left no doubt whatsoever as to which local candidates had commissioned it: the list of a local city councilwoman’s attributes took almost twice as long for the robot voice to utter, at a level of clarity that made the other candidates’ briefer, purely factual blurb sound, well, distinctly inferior. Even his name was pronounced less distinctly. To anyone even vaguely familiar with how polls are constructed, it was completely obvious that the questions had, at best, been constructed to maximize the probability of certain responses, something that legitimate pollsters take wincing pains to avoid, as well as to cajole innocent phone-answerers into listening to an endorsement for a political candidate.

To be blunt, I haven’t heard such obvious plugging since the last time I attended a party at a literary conference, when an agent leaned over me in a hot tub to pitch a client’s book at the editor floating next to me. In fact, it’s the only push poll I’ve ever encountered that actually made me change my mind about voting for a candidate that I formerly respected.

{Present-day Anne here: FYI, she lost.}

Why am I telling you fine people about this at all, since I seldom write here on political issues and I haven’t mentioned who the commissioning candidate was ? (And I’m not going to — the pushed candidate is someone who has done some pretty good things for the city in the past, and is furthermore reputed to be a holy terror to those who cross her — although something tells me it may crop up when I share this story with my neighbors at the July 4th potluck. Unlike the polling firm, I’m not out to affect the outcome of the election.)

I’m bringing it up because of what writers can learn from this handily-timed phone call. True, we could glean from it that, obviously, far too much of my education was devoted to learning about how statistics are generated. A savvy interpreter might also conclude that cutting campaign expenditures by hiring polling firms that use badly-faked human voices is penny-wise and pound-foolish.

But most vital to our ongoing series, in an interview scene, it’s important to make it clear who is the information-solicitor and who the information-revealer.

If the interviewer’s biases are heavy-handedly applied, he/she/the computer-generated voice appears to be trying to influence the content of the answers by how the questions are phrased. (As pretty much all political poll questions are designed to do; sorry to shatter anyone’s illusions on the subject, but I’ve written them in the past.) While a pushy interviewer can make for an interesting scene if the interviewee resists his/her/its ostensibly subtle blandishments, the reader may well side against a protagonist who interviews like a push-poller.

The moral of the story: impartial questions are actually rather rare in real life. When constructing an interview scene, it’s vital to be aware of that — and how much interviewees tend to resent being push-polled, if they realize that’s what’s happening.

Got all that? Good. Because the plot is about to thicken in an even more instructive way. Let us return to our story of civic communicative ineptitude, already in progress.

Being a good citizen, as well as having more than a passing familiarity with how much a poorly-executed campaign ad (which this poll effectively was) can harm an otherwise praiseworthy candidate, I took the time out of my busy schedule to drop the campaign manager an e-mail. I felt pretty virtuous for doing this: I was probably not the only potential voter annoyed by the pseudo-poll, but I was probably the only one who would actually contact the campaign to say why.

You know me; I’m all about generating useful feedback.

So I sent it off and thought no more about it — until this morning, when the campaign manager sent me the following e-mailed reply:

Dear Dr. Mini,

Thank you for your comments. We appreciate the feedback on any of our voter contact and outreach efforts. In everything we do, we want to make the best and most professional impression. You are right that automated surveys are cost competitive {sic}. In this situation, the need for feedback from voters was important {sic} and we hope that almost everyone was able to hear the questions clearly.

I have included the following link to an article on what push polling is {sic} (address omitted, but here’s the relevant link). I assure you that our campaign does not and will not ever be involved in push polling.

Thank you for supporting (his candidate) for Mayor {sic}.

At first glance, this appears to be a fairly polite, if poorly punctuated, response, doesn’t it? He acknowledged the fact that I had taken the time to communicate my critique, gave a justification (albeit an indirect one) for having used computerized polling, and reassured an anxious potential voter that his candidate’s policy was to eschew a practice that I had informed him I found offensive.

On a second read, he’s saying that he’s not even going to check in with the pollsters to see if my objections were valid, since obviously I am stone-deaf and have no idea what push polling is. Oh, and since push polling is bad, and his candidate is not bad, therefore no polls commissioned on her behalf could possibly be push polling. Thank you.

In short: vote for my candidate anyway, so I may head up the future mayor’s staff. But otherwise, go away, and you shouldn’t have bugged me in the first place.

To add stupidity icing to the cake of insolence, the article to which he referred me for enlightenment on how I had misdefined push polling confirmed my use of the term, not his: “A call made for the purposes of disseminating information under the guise of survey is still a fraud – and thus still a ‘push poll’ – even if the facts of the ‘questions’ are technically true or defensible.”

Wondering again why I’m sharing this sordid little episode with you? Well, first, to discourage any of you from making the boneheaded mistake of not bothering to read an article before forwarding the link to somebody. An attempt to pull intellectual rank is never so apparent as when if falls flat on its face.

Second, see how beautifully his resentment that I had brought up the issue at all shines through what is ostensibly a curt business letter, one that he probably thought was restrained and professional when he hit the SEND key? If any of you is ever tempted to respond by e-mail, letter, or phone to a rejection from an agent or editor, this is precisely why you should dismiss the idea immediately as self-destructive: when even very good writers are angry, they tend not to be the best judges of the tone of their own work.

And when a writer is less talented…well, you see the result above.

Another reason you should force yourself not to hit SEND: such follow-ups are considered both rude and a waste of time by virtually everyone in the industry. (For a fuller explanation why, please see my earlier post on the subject.) Like a campaign manager’s telling an offended voter that her concerns are irrelevant for semantic reasons, it’s just not a strategy that’s at all likely to convince your rejecter that his earlier opinion of you was mistaken.

Trust me: I’ve been on every conceivable side of this one. Just hold your peace — unless, of course, you would like the recipient of your missive to do precisely what I’ve done here, tell everyone within shouting distance precisely what happened when you didn’t observe the standing norms of professionalism and courtesy.

Yes, it happens. As you see, the anecdote can be made very funny.

Okay, back to the business at hand. Last time, I sensed some of you writers of first-person narratives cringing at the prospect of minimizing the occurrence of Hollywood narration in your manuscripts.

Oh, don’t deny it: at least 10% of you novelists, and close to 100% of memoir-writers — read through my excoriation of Hollywood narration and thought, “Oh, no — my narrator is CONSTANTLY updating the reader on what’s going on, what has gone on, other characters’ motivations, and the like. I thought that was okay, because I hear that done in movies all the time. But if Hollywood narration on the printed page is one of Millicent the agency screener’s numerous pet peeves, I’d better weed out anything in my manuscript that sounds remotely like screenplay dialogue, and pronto! But where should I begin? HELP!”

Okay, take a deep breath: I’m not saying that every piece of movie-type dialogue is a red flag if it appears in a manuscript. What I’ve been arguing is that including implausible movie-type dialogue can be fatal to a manuscript’s chances.

Remember, in defining Hollywood narration, I’m not talking about when voice-overs are added to movies out of fear that the audience might not be able to follow the plot otherwise — although, having been angry since 1982 about that ridiculous voice-over tacked onto BLADE RUNNER, I’m certainly not about to forgive its producers now. (If you’ve never seen either of the released versions of the director’s cut, knock over anybody you have to at the video store to grab it from the shelf. It’s immeasurably better — and much closer to the rough cut that Philip K. Dick saw himself before he died. Trust me on this one.)

No, I’m talking about where characters suddenly start talking about their background information, for no apparent reason other than that the plot or character development requires that the audience learn about the past. If you have ever seen any of the many films of Steven Spielberg, you must know what I mean. Time and time again, his movies stop cold so some crusty old-timer, sympathetic matron, or Richard Dreyfus can do a little expository spouting of backstory.

You can always tell who the editors in the audience are at a screening of a Spielberg film, by the way; we’re the ones hunched over in our seats, muttering, “Show, don’t tell. Show, don’t tell!” like demented fiends.

I probably shouldn’t pick on Spielberg (but then, speaking of films based on my friend Philip’s work, have I ever forgiven him for changing the ending of MINORITY REPORT?), because this technique is so common in films and television that it’s downright hackneyed. Sometimes, there’s even a character whose sole function in the plot is to be a sort of dictionary of historical information.

For my nickel, the greatest example of this by far was the Arthur Dietrich character on the old BARNEY MILLER television show. Dietrich was a humanoid NEW YORK TIMES, PSYCHOLOGY TODAY, SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, and KNOW YOUR CONSTITUTION rolled up into one. (He also, several episodes suggested, had a passing familiarity with the KAMA SUTRA as well — but hey, it was the ‘70s.) Whenever anything needed explaining, up popped Dietrich, armed with the facts: the more obscure the better.

The best thing about the Dietrich device is that the show’s writers used it very self-consciously as a device, rather than pretending that it wasn’t. The other characters relied upon Dietrich’s knowledge to save them research time, but visibly resented it as well. After a season or so, the writers started using the pause where the other characters realize that they should ask Dietrich to regurgitate as a comic moment.

(From a fledgling writer’s perspective, though, the best thing about the show in general was the Ron Harris character, an aspiring writer stuck in a day job he both hates and enjoys while he’s waiting for his book to hit the big time. Even when I was in junior high school, I identified with Harris.)

Unfortunately, human encyclopedia characters are seldom handled this well, nor is conveying information through dialogue. Still, as we discussed yesterday, most of us have become accustomed to it, so people who point it out seem sort of like the kid in THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES:

”Why has Mr. Spielberg stopped the action to let that man talk for three solid minutes about backstory, Mommy?”

”Hush, child. There’s nothing odd about that. In film, it’s an accepted narrative convention.”

In a book, there’s plenty odd about that, and professional readers are not slow to point it out. It may seem strange that prose stylists would be more responsible than screenwriters for reproducing conversations as they might plausibly be spoken, but as I keep pointing out, I don’t run the universe.

I can’t make screenwriters –or political operatives — do as I wish; I have accepted that, and have moved on.

However, as a writer and editor, I can occasionally make the emperor put some clothes on, if only for the novelty of it. And I don’t know if you noticed, but wasn’t it far more effective for me to allow the campaign manager to hang himself with his own words, allowing the reader to draw her own conclusions about his communication skills and tact levels before I gave my narrative opinion of them, rather than the other way around? Trick o’ the trade.

Trust me, when Millicent is pondering submissions, you want your manuscript to fall into the novelty category, not the far more common reads-like-a-movie-script pile. Which, as often as not, also serves as the rejection pile.

No, I’m not kidding about that. By and large, agents, editors, and contest judges share this preference for seeing their regents garbed — so much so that the vast majority of Millicents are trained simply to stop reading a submission when it breaks out into Hollywood narration. In fact, it’s such a pervasive professional reader’s pet peeve that I have actually heard professional readers quote Hollywood narration found in a submitted manuscript aloud, much to the disgusted delight of their confreres.

Funny to observe? Oh, my, yes — unless you happen to be the aspiring writer who submitted that dialogue.

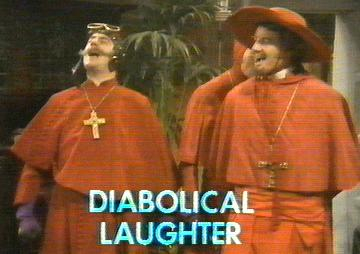

What may we learn from this degrading spectacle? At minimum, that if your characters tell one another things they already know is not going to win your manuscript any friends. There’s a lesson about bad laughter to be learned here as well: if a device is over-used in submissions — as Hollywood narration undoubtedly is — using it too broadly or too often in a manuscript can in and of itself provoke a bad laugh from a pro.

And that, too, is bad, at least for your manuscript’s prospects of making it past Millicent. As a general rule of thumb, one bad laugh is enough to get a submission rejected.

This danger looms particularly heavily over first-person narratives, especially ones that aspire to a funny voice. All too often, first-person narratives will rely upon the kind of humor that works when spoken — the anecdotal kind, the kind so frequently used in onscreen Hollywood narration — not realizing that pretty much by definition, a spoken joke does not contain sufficient detail to be funny on the printed page.

Especially on a printed page where the narrator is simultaneously trying to sound as if he’s engaging the reader in everyday conversation and provide the necessary backstory for the reader to follow what’s going on. Think, for instance, of the stereotypical voice-over in a film noir:

Someone kicked my office door down, and this blonde walked in on legs that could have stretched from here to Frisco and back twice, given the proper incentive. She looked like a lady it wouldn’t be hard to incite.

Now, that would be funny spoken aloud, wouldn’t it? On the page, though, the reader would expect more than just a visual description — or at any rate, a more complex one.

Present-day Anne breaking in again here, feeling compelled to point out two things. First, people from San Francisco have historically hated it when others refer to it as Frisco, by the way. It’s safe to assume that Millicent from there will, too.

Second, and more important for revision purposes, memoirs fall into this trap ALL THE TIME — and it’s as fatal a practice in a book proposal or contest entry as it is in a manuscript. It may be counterintuitive that an anecdote that’s been knocking ‘em dead for years at cocktail parties might not be funny — or poignant, for that matter — when the same speech is reproduced verbatim on the page, but I assure you that such is the case.

The result? Any Millicent working for a memoir-representing agent spends days on end scanning submissions that read like this:

So there I was, listening to my boss go on and on about his fishing vacation, when I notice that he’s got a hand-tied fly stuck in his hair. I’m afraid to swipe my hand at it, because I might end up with a hook in my thumb, and besides, Thom hadn’t drawn breath for fifteen minutes; if the room had been on fire, he wouldn’t want to be disturbed.

The fly keeps bobbing up and down. I keep swishing my bangs out of my eyes, hoping he will start to copy me. Then he absent-mindedly started to shove his hair out of his eyes — and rammed his pinkie finger straight into the fly. That’s a fish story he’ll be telling for years!

Did those paragraphs make your hands grope unconsciously for highlighting pens and correction fluid? After all of our discussion of Frankenstein manuscripts and how to revise them, I sincerely hope so. Like so many verbal anecdotes, this little gem wanders back and forth between the past and present tenses, contains run-on sentences, and is light on vivid detail.

For our purposes today, however, what I want you to notice is how flat the telling is. Both the suspense and the comedy are there, potentially, but told this tersely, neither really jumps off the page at the reader. It reads like a summary, rather than as a scene.

It is, in short, told, not shown. The sad part is, the more exciting the anecdote, the more this kind of summary narration will deaden the story.

Don’t believe me? Okay, snuggle yourself into Millicent’s reading chair and take a gander at this sterling piece of memoir, a fairly representative example of the kind of action scene she sees in both memoir and autobiographical fiction submissions:

The plane landed in the jungle, and we got off. The surroundings looked pretty peaceful, but I had read up on the deadly snakes and vicious mountain cats that lurked in the underbrush. Suddenly, I heard a scream, and Avery, the magazine writer in the Bermuda shorts, went down like a sacked football player. He hadn’t even seen the cat coming.

While I was bending over him, tending his slashed eye, an anaconda slowly wrapped itself around my ankle. By the time I noticed that I had no circulation in my toes, it was too late.

Now, that’s an inherently exciting story, right? But does the telling do it justice? Wouldn’t it work better if the narrative presented this series of events as a scene, rather than a summary?

Ponder that, please, as we return to the discussion already in progress.

To professional readers, humor is a voice issue. Not many books have genuinely amusing narrative voices, and so a good comic touch here and there can be a definite selling point for a book. The industry truism claims that one good laugh can kick a door open; in my experience, that isn’t always true, but if you can make an agency screener laugh out loud within the first page or two of a partial, chances are good that the agency is going to ask to see the rest of the submission.

But think about why the Frisco example above made you smile, if it did: was if because the writing itself was amusing, or because it was a parody of a well-known kind of Hollywood narration? (And in the story about the campaign manager, didn’t you find it just a trifle refreshing that he didn’t speak exactly like a character on THE WEST WING?)

More to the point, if you were Millicent, fated to screen 50 manuscripts before she can take the long subway ride home to her dinner, would you be more likely to read that passage as thigh-slapping, or just another tired piece of dialogue borrowed from the late-night movie?

The moral, should you care to know it: just because a writer intends a particular piece of Hollywood narration to be funny or ironic doesn’t necessarily mean that it won’t push the usual Hollywood narration buttons.

I shudder to tell you this, but the costs of such narrative experimentation can be high. If a submission tries to be funny and fails — especially if the dead-on-arrival joke is in the exposition, rather than the dialogue — most agents and editors will fault the author’s voice, dismissing it (often unfairly) as not being fully developed enough to have a sense of its impact upon the reader. It usually doesn’t take more than a couple of defunct ducks in a manuscript to move it into the rejection pile.

I hear some resigned sighing out there. “Okay, Anne,” a few weary voices pipe, “you’ve scared me out of the DELIBERATE use of Hollywood narration. But if it’s as culturally pervasive as you say it is, am I not in danger of using it, you know, inadvertently?”

The short answer is yes.

The long answer is that you’re absolutely right, weary questioners: we’ve all heard so much Hollywood Narration in our lives that it is often hard for the author to realize she’s reproducing it. Here is where a writers’ group or editor can really come in handy: before you submit your manuscript, it might behoove you to have an eagle-eyed friend read through it, ready to scrawl in the margins, “Wait — doesn’t the other guy already know this?”

So can any other good first reader, of course, if you’re not into joining groups, but for the purposes of catching Hollywood narration and other logical problems, more eyes tend to be better than fewer. Not only are multiple first readers more likely to notice any narrative gaffe than a single one — that’s just probability, right? — but when an aspiring writer selects only one first reader, he usually chooses someone who shares his cultural background.

His politics, in other words. His educational level. His taste in television and movie viewing — and do you see where I’m heading with this? If you’re looking for a reader who is going to flag when your dialogue starts to sound Spielbergish, it might not be the best idea to recruit the person with whom you cuddle up on the couch to watch the latest Spielberg flick, might it?

I just mention.

One excellent request to make of first readers when you hand them your manuscript is to ask them to flag any statement that any character makes that could logically be preceded by variations upon the popular phrases, “as you know,” “as I told you,” “don’t you remember that,” and/or “how many times do I have to tell you that…”

Ask them to consider: should the lines that follow these statements be cut? Do they actually add meaning to the scene, or are they just the author’s subconscious way of admitting that this is Hollywood narration?

Another good indicator that dialogue might be trending in the wrong direction: if a character asks a question to which s/he already knows the answer (“Didn’t your brother also die of lockjaw, Aunt Barb?”), what follows is pretty sure to be Hollywood narration.

Naturally, not all instances will be this cut-and-dried, but these tests will at least get you into the habit of spotting them. When in doubt, reread the sentence in question and ask yourself: “What is this character getting out making this statement, other than doing me the favor of conveying this information to the reader?”

Flagging the warning signs is a trick that works well for isolated writers self-editing, too: once again, those highlighter pens are a revising writer’s best friends. Mark the relevant phrases, then go back through the manuscript, reexamining the sentences that surround them to see whether they should be reworked into more natural dialogue.

And while you’re at it, would you do me a favor, please, novelists? Run, don’t walk, to the opening scene of your novel (or the first five pages, whichever is longer) and highlight all of the backstory presented there. Then reread the scene WITHOUT any of the highlighted text.

Tell me — does it still hang together dramatically? Does the scene still make sense? Is there any dialogue left in it at all?

If you answered “By gum, no!” to any or all of these questions, sit down and ponder one more: does the reader really need to have all of the highlighted information from the get-go? Or am I just so used to voice-overs and characters spouting Hollywood narration that I thought it was necessary when I first drafted it but actually isn’t?

Okay, that’s more than enough homework for one day, I think, and enough civic involvement for one day. Keep up the good work!