No, the photo above isn’t a representation of what a stand of trees might look like through allergy-blurred eyes — although the lilac tree in my back yard has apparently decided that this is the year to make its shot at shattering all previous records for pollen production. It’s a shot of blinding sunlight coming through trees, taken while I was ineffectually exclaiming, “Wait! Slow down! That would be a beautiful shot!”

Sometimes, all you get is a momentary glimpse of what’s going on around you. Blink, and it’s gone.

That’s a darned hard experience to replicate on the page, isn’t it? Particularly in an action scene shown simultaneously from several different perspectives: as tempting as it may be to include blow-by-blow accounts from every relevant point of view, once the reader knows a punch was thrown, an instant replay from another perspective may strike him as redundant — or even confusing.

How often did Sluggo swing? Was the fist that just went by Protagonist #2’s cheekbone the same one that Protagonist #3 just mentioned sending in his general direction, or did it belong to Protagonist #4? And pardon my asking, but did it just take 3/4 of a page of text to show three punches?

Revisers sit in front of action scenes like this, grinding their teeth in frustration. “How on earth,” they cry as soon as they can force their molars apart, “can I clarify what’s going on here without slowing the scene down to a crawl? Perhaps neither Anne nor Millicent the agency screener would notice if I switched the scene to a bystander’s perspective, so I don’t need to deal with the fighters’ points of view until the battle has died down.”

Nice try, teeth-grinders, but trust me, Millicent knows all about that evasive maneuver. And I know you’re far too serious about craft to take the tawdry easy way out of a narrative conundrum.

And to those of you jumping up and down, screaming, “Wait — tell me about the easy way! I long to embrace the tawdry short cut!”, I’m not listening.

I can sympathize, however, with a certain amount of shock at being flung with barely a preamble straight into the heart of our knotty problem du jour. For the sake of those ground-down molars, I’ll back up and ease into it a trifle more gently.

Last time, we discussed means of allowing tight third-person narrative to reflect individual quirks in depicting a particular scene. Rather than the protagonist’s presence or participation alone casting her primary shadow across the scene, I suggested infusing the text with her worldview, unique powers of observation, and other characteristics. This works marvelously as a method of differentiating between multiple protagonists’ sections of a novel, whether it is written in the third or first person.

Actually, it’s kind of a nifty trick in a single-protagonist novel, too, and definitely in a biography or memoir. Whenever the world is being shown from a specific point of view, I think it’s interesting when the narrative reflects the unique observational style of the teller.

Differentiation can get tricky, though, in a book with scads of protagonists. With two or three, the variations in observation can be fairly subtle, but if you try it with twelve, the reader is likely to lose track of whether Penelope’s frequent sneezes are the result of a canary-in-a-coal-mine sensitivity to mold due to that summer she spent on an archeological dig in a swamp, or if that was Tim’s excuse, and Penelope was the one who abhorred grass ever since that terrible day on the football field.

Or maybe it’s just hay fever season. There’s a limit to how many subtleties the reader can reasonably be expected to remember — and we writers tend to forget that.

“What do you mean, Tina’s fatal wool allergy came out of left field in Chapter 26?” we exclaim indignantly when our manuscripts are critiqued. “She cleared her throat twice next to Eliot’s sweater in Chapter 3!”

I hate to admit it, but personal quirks and background dissimilarities can be overdone; a protagonist with 137 pet peeves is probably going to annoy a reader more than one with 13. But now that I’ve gotten you into the habit of looking at your various protagonists’ sections of the text with an eye to varying them, let’s talk about means of increasing individuality in a protagonist’s section of narrative without taxing the reader’s memory banks.

What if, for instance, the vocabulary were quite different in Protagonist A’s sections of the text and Protagonist B’s?

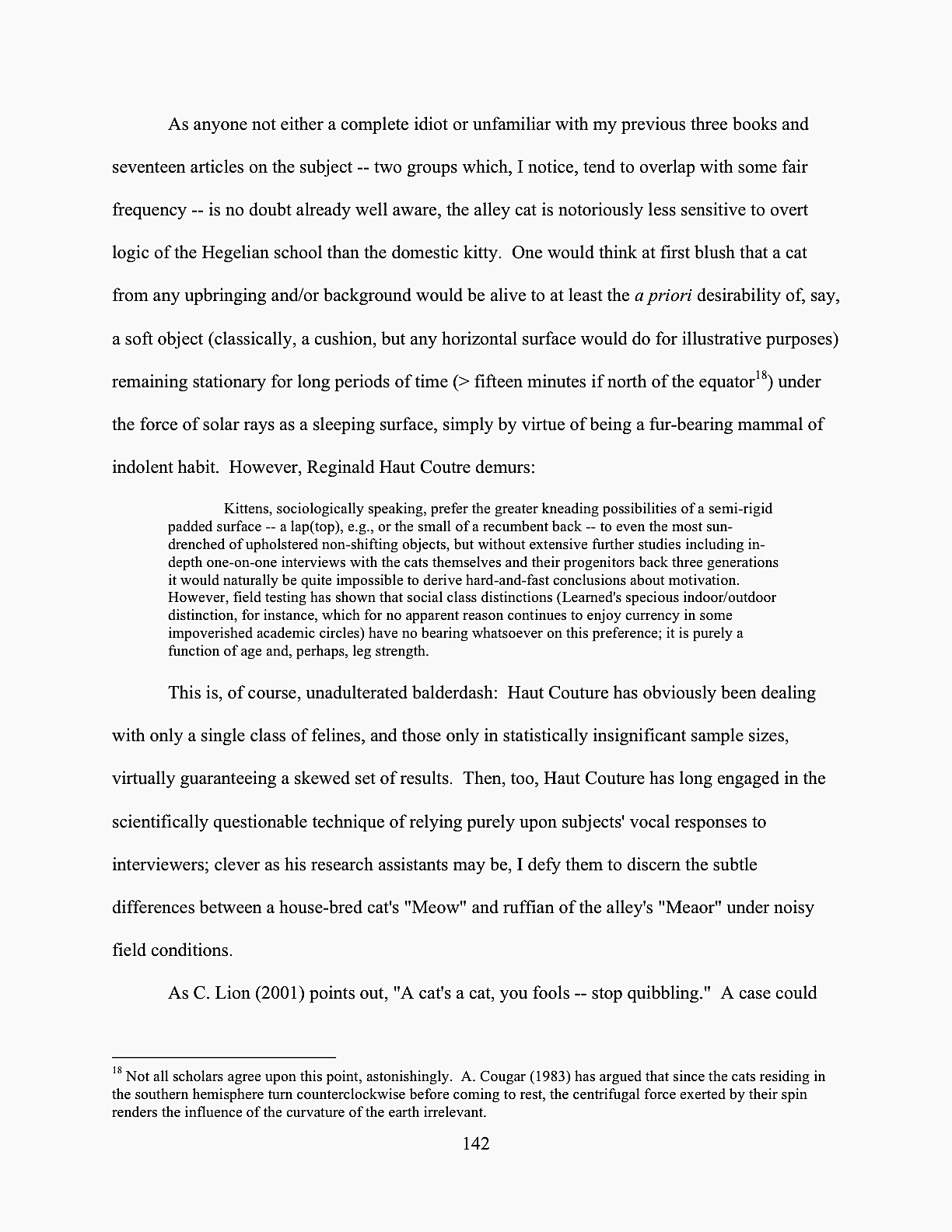

This is a characterization trick lifted from dialogue, of course: no one expects a character with a Ph.D. to speak in the same manner as a character who did not graduate from high school, right? If there are polysyllabic words to be uttered, they’re going to be spilling out of the professor’s mouth.

Indeed — as my fellow Ph.D.s complain amongst themselves early and often — professor characters are often depicted as emitting lecture-quality logic every waking second. Frankly, we real-life professors find this expectation exhausting to contemplate. Even Socrates took some time off from asking annoying questions from time to time.

And look where that got him.

Did you catch the narrative trick I just pulled? I underscored my narrative credibility as a professor by dropping in a philosophy joke. Not a bad investment of just a couple of lines of text, and certainly more interesting for most readers than if I had inserted a five-page essay on the Socratic method.

Or if I had simply started spouting a whole lot of technical terms specific to my former academic field, for that matter. While every profession has its jargon, it doesn’t necessarily render a narrator or speaker more credible to overuse it on the page. What over-reliance upon any field’s jargon is far more likely to produce is in readers is boredom.

Oh, you like it when a mushroom specialist corners you at a party and starts talking spores non-stop? Unless you share her passion for fungi, you’re probably going to be looking to change the subject pretty darned soon.

Because I have lecturing experience, I recognize that the forest of hands waving in the air means that at least some of you have questions about that last observation. (I’m a professional, though; the layperson shouldn’t attempt leaping to that sort of lofty conclusion at home.) Yes, hand-raisers?

“I would be reluctant to include a joke like the one you used above,” they point out, rubbing circulation back into their arms, “even if it conveys something significant about that narrator’s background. The build-up and joke assume that the reader is aware that Socrates went around asking his fellow 5th century BC Athenians probing philosophical questions, eventually irritating them enough that they condemned him to death. Not every reader would know that. But as you may see from the length of this very paragraph, devoting text to explaining the joke would not only slow down the scene already in progress — or even bring it to a screeching halt. So I ask you: is this really effective character development?”

In a word: yes. Moving on…

Just kidding. Actually, the answer depends upon the intended readership for the book: just as it’s safer to assume that 15-year-old readers will recognize current teenage jargon than 50-year-olds (and that the 15-year-olds will find it embarrassing when the 50-year-olds try to sound hip by using it), it’s more reasonable to expect literary fiction readers to catch more historical and literary references than, say, the target audience for terse Westerns. By the same token, a Western writer could get away with presuming that her target readership knew a heck of a lot more about horses than the average reader of literary fiction.

The same holds true for vocabulary choices, of course: since every book category has a pretty well-established reading level, sticking to the one an agent or editor would expect to see in your kind of book just makes good marketing sense. (If you’re not familiar with the expected reading level for your chosen book category, run, don’t walk to the nearest well-stocked bookstore and spend a couple of hours leafing through books like yours, to see what kind of vocabulary they use.) Within those parameters, though, a writer has quite a bit of wiggle room for showing well-read narrators sounding well-read on the page.

In other words: go ahead and let your various protagonists’ speech patterns color the narrative in sections written from their respective perspectives. Just don’t get so carried away with professional jargon that a reader from another field can’t understand what he’s saying — or gives up trying.

This logic is surprisingly infrequently extended to third-person narrative from multiple perspectives. (One sees it applied to first-person narratives more frequently, but then, many first-person narratives are crafted to resemble speech.) But think about it: why wouldn’t a well-read fifth grader’s fine vocabulary extend into her thoughts?

A couple of words of warning about applying this technique to multiple-perspective novel: first, try not to overdo it. If the differences are too extreme, you run the risk of the characters with the smaller vocabularies coming across as a tad dim-witted. Bear in mind that smart people aren’t necessarily well-educated or widely read, after all, and — dare I say it? — not all well-educated people are necessarily smart.

Trust me on this one. I’ve spent quite a bit of time in faculty meetings.

Second, it is very easy to overuse professional jargon. (Wait, where have I heard that before?) Sprinkle it about, by all means, but do be aware that doctors who use the Latin names for common body parts three times a paragraph, emergency room nurses who add, “STAT!” to half their sentences, and lawyers who pepper their conversations and thoughts with whereases and heretofores are a notorious agency screener’s pet peeve.

I just mention. Just because something happens in real life does not necessarily mean it will work in print — or in a submission. Treat the use of jargon associated with particular jobs like any other stereotype: there’s always more to an individual than the obvious.

My next suggestion for individualizing your protagonists’ perspectives is even more fundamental: what if the narrative changed rhythm when the perspective altered?

I’m not talking about anything radical, such as Protagonist A’s sections utilizing exclusively short, declaratory sentences while Protagonist B’s abound in run-ons. (Which I’ve seen in quite a few manuscripts, by the way.) But could the habitual coffee-drinker’s musings pass by the reader like a highly caffeinated freight train, while the obsessively orderly person’s flights of fancy always get cut off short of running amok?

Has some intriguing possibilities, doesn’t it?

The conceivable variations are practically endless — and again, are as useful for constructing dialogue as for narrative. An 80-year-old man with a lung condition would probably speak in shorter bursts than a 25-year-old jogger; differences in lung capacity alone would dictate that, right? Where the speech goes, the thought can surely follow: when the body’s having trouble breathing, wouldn’t you expect that to disrupt, say, lengthy stretches of otherwise uninterrupted thought?

Actually, I would urge you to give some thought into working bodily rhythms into your writing in general; in tight third-person narrative, it’s not done much. There are few novels out there that take situational variations in breathing and heart rate into account at all, even in dialogue during heavy action scenes.

People tend not to have a whole lot of extra breath to talk in the middle of hand-to-hand combat, something screenwriters would do well to remember. Similarly, we might expect a protagonist’s thoughts would tend to run shorter in a moment of imminent crisis than in a moment of calm.

Switching to short, choppy sentences convey a subtle impression of panting breath and elevated heart rate, incidentally, especially if such sentences appear in tandem only in such scenes. Trick o’ the trade.

Just as the best means of catching rhythmic patterns is to read text out loud, the best means of determining what is a realistic bodily response is to act a scene out. Within reason, of course: obviously, if you’re writing about a killer, I’m certainly not advising that you test-drive the mayhem. However, if your protagonist has been carrying a 50-pound suitcase without wheels for 20 pages, your sense of the probable effects upon his body will definitely be heightened if you carry around a heavy suitcase for 10 or 15 minutes.

Actually, it’s not a bad idea to test the plausibility of everyday events in your books in general; unverified timing is frequently implausible on the page. You’d be amazed at how many books contain speeches that could not be said within a single breath, for instance, and what a high percentage of exchanges ostensibly between floors in elevators would require three consecutive trips to the top of the Empire State Building to complete.

Admittedly, a writer does occasionally risk astonishing bystanders by this kind of vigorous fact-checking. I once spent a humid Chicago afternoon frightening small children in a park trying to figure out the various body parts that might get bruised if one got jumped from behind while sitting on a park bench. It’s astonishing what one’s friends will do for free pizza, and the scene was better for it.

It’s possible to predict certain reactions without engaging in amateur dramatics, of course. If your protagonist has just chased a mugger for two and half city blocks, or dashed up a flight of stairs because she’s afraid of being late for her first day of work, or flung herself down a manhole to escape the marauding living dead who want to eat her brain, it’s reasonable to expect that her heart will be pounding and her breath drawing short.

No need to recruit the local zombies to ascertain that.

Oh, dear, there are all of those raised hands again. You want to raise a practical difficulty? “I’m open to incorporating any or all of these techniques, Anne, but while we’re talking about action scenes, I want to raise a different sort of practical difficulty. How does one depict an action scene between two people of the same sex without repeating each of their names constantly?”

Wow, that is practical. To make sure everyone knows what the hand-raisers are talking about, let’s take a gander at the combatants in this action-packed paragraph:

Herb pulled the truncheon from his belt and swung it at Trevor. Trevor ducked, avoiding the blow. Herb, having thrown his entire substantial body weight behind the swing, lost his balance. Trevor leaped onto his back the instant Herb hit the ground, pounding Herb’s head into the pavement.

“Admit that Gene Wilder was a better Willy Wonka than Johnny Depp!” Trevor howled, grinding Herb’s nose unpleasantly along the sidewalk.

“Never!” Herb shouted, flinging Trevor off him.

That’s a whole lot of proper noun repetition, isn’t it? Yet the names could not plausibly be replaced with pronouns without causing abundant confusion:

He pulled the truncheon from his belt and swung it at him. He ducked, avoiding the blow. Having thrown his entire substantial body weight behind the swing, he lost his balance. He leaped onto his back the instant he hit the ground, pounding his head into the pavement.

“Admit that Gene Wilder was a better Willy Wonka than Johnny Depp!” he howled, grinding his nose unpleasantly along the sidewalk.

“Never!” he shouted, flinging him off him.

Faced with this difficulty, many revisers will leap to compensate. Descriptors could be used to take the place of some of the hims, naturally, but the result is still a bit cumbersome:

Herb pulled the truncheon from his belt and swung it at Trevor. The smaller man ducked, avoiding the blow. The mustachioed aggressor, having thrown his entire substantial body weight behind the swing, lost his balance. The diminutive and swarthy one leaped onto his perplexed left-handed assailant’s back the instant he hit the ground, pounding his brother’s head into the pavement.

“Admit that Gene Wilder was a better Willy Wonka than Johnny Depp!” he howled, grinding his lifelong best friend and canasta partner’s nose unpleasantly along the sidewalk.

Feels a touch over-explained, doesn’t it? Complex perspective can be very helpful reducing this sort of verbosity.

And you’d thought that I wasn’t going to tie it back to the earlier part of the blog, hadn’t you? Au contraire.

The more deeply the reader is embroiled Herb’s perspective, the more sense it makes to show action and reaction not as external to him, but as part of his rich and varied experience of life.

Okay, so maybe that was overstating it just a tad. But just look at how easily this method clears things up:

His truncheon seemed an extension of his frustration: carrying his entire substantial body weight behind it, it flashed toward Trevor’s face. The wily bastard ducked, avoiding the blow, just as he had dodged every responsibility in their collective lives.

Flailing for balance, Herb felt fists on his back before he hit the ground. What kind of brother pounds your head into wet pavement?

When you’re dealing in enriched perspective, an action scene is never just about the action in it. It becomes another opportunity for character development, for revealed observation, and — dare I say it? — clarifying perspective.

That’s my perspective on it, anyway. Keep up the good work!