My apologies about the uncharacteristic multi-day silence, campers — once one of the houseguests discovered just how comfy my desk chair was, I couldn’t get near it again. An alien laptop invaded my desk for days on end. Which just goes to show you that as delightful as it can be to nab the most engaging room in the house for one’s writing space, it has its drawbacks.

Back to business, therefore, toute suite. After my last post on the desirability of minimizing and repetition, clever and insightful reader Adam made an observation that caused me to pause, take three steps back from our ongoing series, and reassess my methodology. Quoth Adam:

This really is helpful. Not even so much about this particular conjunction, but the habit of viewing one’s manuscript on a multitude of levels. Learning to read one’s own work with poor Millie’s eyes is one, though what caught my attention this time around perhaps relates to your posts on MS format: how the appearance of a page or the prevalency of particular words on a page can stand out just as much or more than the meaning we want to convey.

The bit about the habit of viewing one’s manuscript on a multitude of levels leapt out at me, I must confess. Egads, thought I, in discussing how to diagnose the many and varied ills that frequently plague the Frankenstein manuscript — that frightening entity written by a single author, but reads as though it had been written by several, so inconsistent are the voices, perspectives, and even word choices throughout — had I encouraged my readers to place their noses so close to the page that the larger picture has started to blur? In applying tender loving care to the scars holding together the Frankenstein manuscript, had we lost sight of the entire creature?

Nah, I thought a moment later. But I may not have made it perfectly clear yet that different types of revision, or even revision based upon different varieties of feedback, can yield quite different results.

Why worry about such niceties, when your garden-variety Frankenstein manuscript could, quite frankly, use quite a bit of scar-buffing to get it ready for prom night? (Bear with me while I’m breaking my metaphor-generator back in, please — my desk is evidently out of practice.) Contrary to popular belief, even amongst writers who should know better, there is no such thing as a single best way to revise a narrative, any more than there is a single best way to tell a story.

Part of the charm of individual authorial voice is that it is, in fact, individual — but you’d never glean that from how writers (and writing teachers) tend to talk about revision. All too often, we speak amongst ourselves as though the revision process involved no more than either (a) identifying and removing all of the objectively-observable mistakes in a manuscript, or (b) changing our minds about some specific plot point or matter of characterization, then implementing it throughout the manuscript.

These are two perfectly reasonable self-editing goals, of course, but they are not the only conceivable ones. When dealing with a Frankenstein manuscript — as pretty much every writer does, at least in a first book — a conscientious self-editor might well perform a read-through for voice consistency, another for grammatical problems, a third for logic leaps, a fourth because the protagonist’s husband is no longer a plumber but the member of Congress representing Washington’s 7th District…

And so forth. Revision can come in many, many flavors, variable by specificity, level of focus, the type of feedback to which the writer is responding, and even the point in publication history at which the manuscript is being revised.

Does that all sound dandy in theory, but perplexing in practice? Don’t worry; I haven’t been away from my desk so long that I have forgotten that I am queen of the concrete example. To help you gain a solid sense of how diverse different of levels of revision can be, I’m going to treat you to a page from one of my favorite fluffy novels of yore, Noël Coward’s Pomp and Circumstance, a lighthearted romp set in a tropical British colony on the eve of a royal visit.

I chose this piece not merely because it retains a surprisingly high level of Frankenstein manuscript characteristics for a work by a well-established writer (possibly because it was Coward’s only published novel), or even because it deserves another generation of readers. (As it does; his comic timing is unparalleled.) I think it’s an interesting study in how literary conventions change: even at the time of its release in 1960, some critics considered it a bit outdated. Coward’s heyday had been several decades before, they argued, so the type of sex comedy that used to shock in the 1920s was a bit passé, and wasn’t it a bit late in the literary day to steer so firmly away from sociopolitical commentary?

Now, sociopolitical commentary has largely fallen out of style, at least in first novels, and sex, as Coward himself was fond of observing, seems to be here to stay. Here is a page from the end of the book, where our narrator, a harried British matron living on a South Sea island, finds herself entertaining Droopy, the husband of her best friend Bunny’s would-be mistress.

Amusing, certainly, but a bit Frankensteinish, is it not? At first glance, how would you revise it? Would your revision goals be different if this were page 5, rather than page 272?

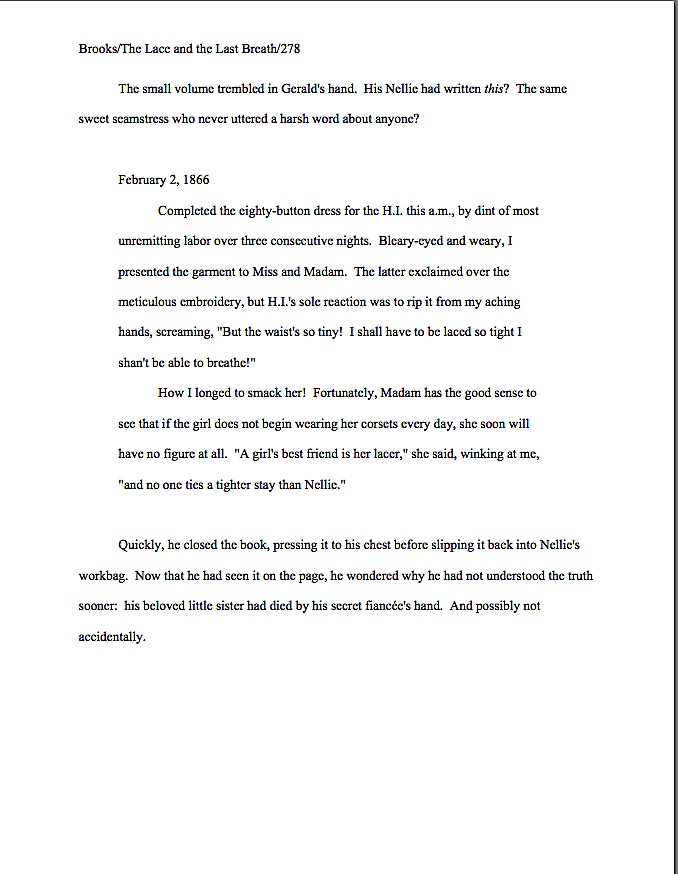

Before you give your final answers, here’s that page again, after it has been subjected to just the kind of repetition-spotting mark-up I’ve been asking you to perform of late. (Sorry about the dark image; I honestly didn’t take the photograph in a particularly gloomy room. If you’re having trouble reading the specifics, try either pressing command + to make the window larger or saving the image to your hard disk.)

Quite a lot of repetition, isn’t it? By today’s book publication standards, as Millicent the agency screener would no doubt be overjoyed to tell you, it would deserve instant rejection on that basis alone. But would you agree? After all, the narrative voice in the excerpt, replete with all of that structural redundancy, actually is not all too far from the kind of writing we all see every day online, or even in the chattier varieties of journalism.

We can all see why some writers would favor this kind of voice, right? Read out loud, this kind of first-person narration can sound very natural, akin to actual speech. So why, do you suppose, would Millicent cringe at the very sight of it?

Those of you who have been following this series on Frankenstein manuscripts faithfully, feel free to sing along: because the level of repetition that works in everyday speech is often hard to take on the printed page.

Now that you see all of those ands and other word repetition marked on the page, you must admit that they are mighty distracting to the eye; by repeating the same sentence structures over and over, our buddy Noël is practically begging Millicent to skip lines while skimming. Nor is all of the redundancy here literal; there’s a certain amount of conceptual repetition as well. Take note of all of those visually-based verbs: not only do people look a great deal, but our heroine envisages AND tries to imagine how she might appear in his eyes.

That should all sound fairly familiar from our recent discussions, right? You might well have spotted all of those problems in your first glance at the non-marked version of the text. But does that mean there’s not any more revision to be done here?

Not by a long shot. Did you catch the over-use of subordinate clauses, all of those whiches in yellow? Back in the day, literature was rife with these; now, most Millicents are trained to consider them, well, a bit awkward. While a tolerant Millie might be inclined to glide past one every ten or fifteen pages, even a screener noted for her restraint would begin to get restless with as many as appear on a single page above.

That almost certainly would not have been a major objection raised by Millicent’s forebears in 1960, however. The literary gatekeepers would have concentrated on quite different parts of this page — the grammatically-necessary missing commas, for instance, and the back-to-back prepositions.

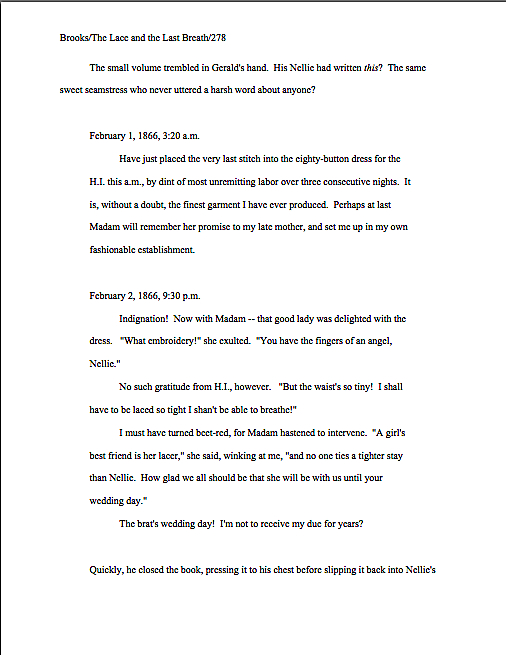

Longing to see how Millicent’s grandmother would have commented on this page? Well, you’re in luck; I just happen to have her feedback handy.

Let’s linger a moment in order to consider Grandma M’s primary quibbles. First, as she points out so politely in red at the top of the page, it takes at least two sentences to form a narrative paragraph. In dialogue, a single-line paragraph is acceptable, but in standard prose, it is technically incorrect.

Was that gigantic clunk I just heard the sound of jaws belonging to anyone who has picked up a newspaper or magazine within the last decade hitting the floor?

In theory, Grandma M is quite right on this point — and more of her present-day descendants would side with her than you might suppose. Millie’s grandmother did not bring her up to regard setting grammar at naught lightly, after all.

But does that necessarily mean it would be a good idea for you to sit down today and excise every single-sentence narrative paragraph in your manuscript? Perhaps not: the convention of occasionally inserting a single-line paragraph for emphasis has become quite accepted in nonfiction. The practice has crept deeply enough into most stripes of genre fiction that it probably would not raise Millicent’s eyebrows much.

How can you tell if the convention is safe to use in your submission? As always, the best way of assessing the acceptability of a non-standard sentence structure in a particular book category is to become conversant with what’s been published in that category within the last few years. Not just what the leading lights of the field have been writing lately, mind you, since (feel free to shout along with me now, long-time readers) what an established author can get away with doing to a sentence is not always acceptable in a submission by someone trying to break into the field. Pay attention to what kinds of sentences first-time authors of your kind of book are writing these days, and you needn’t fear going too far afield.

As a general rule of thumb, though, even first-time novelists can usually get the occasional use of the single-sentence paragraph device past Millicent — provided that the content of the sentence in question is sufficiently startling to justify standing alone. As in:

The sky was perfectly clear as I walked home from school that day, the kind of vivid blue first-graders choose from the crayon box as a background for a smiling yellow sun. The philosopher Hegel would have loved it: the external world mirroring the clean, happy order of my well-regulated mind.

That is, until I tripped over the werewolf lying prone across my doorstep.

Didn’t see that last bit coming, did you? The paragraph break emphasizes the jaggedness of the narrative leap — and, perhaps equally important from a submission perspective, renders the plot twist easier for a skimming eye to catch.

The fact remains, though, that Grandma M would growl at this construction (“My, Granny, what big teeth you have!”), and rightly so. Why? Well, it violates the two-sentences-or-more rule, for starters. In the second place, it really isn’t ever necessary, strictly speaking. In a slower world, one where readers lived sufficiently leisurely lives that they might be safely relied upon to glance at every sentence on a page, all of this information could have fit perfectly happily into a single paragraph. Like so:

The sky was perfectly clear as I walked home from school that day, the kind of vivid blue first-graders choose from the crayon box as a background for a smiling yellow sun. The philosopher Hegel would have loved it: the external world mirroring the clean, happy order of my well-regulated mind. That is, until I tripped over the werewolf lying prone across my doorstep.

I bring this up not only to appease Grandma M’s restless ghost, currently haunting an agency or publishing house somewhere in Manhattan, but so that those of you addicted to single-line paragraphs will know what to do with hanging sentences: tuck ‘em back into the paragraph from whence they came.

At least a few of them. Please?

Really, it’s in your submission’s best interest to use the single-line paragraph trick infrequently, reserving it for those times when it will have the most effect. Why, you ask? Because amongst aspiring writers who like the impact of this structure, moderation is practically unheard-of.

Just ask Millicent; she sees the evidence every day in submissions. Many, if not most, novelists and memoirists who favor this device do not use the convention sparingly, nor do they reserve its use for divulging information that might legitimately come as a surprise to a reasonably intelligent reader.

As a result, Millie tends to tense up a bit at the very sight of a single-sentence paragraph — yes, even ones that are dramatically justifiable. Hard to blame her, really, considering how mundane some of the revelations she sees in submissions turn out to be. A fairly typical example:

The sky was perfectly clear as I walked home from school that day, the kind of vivid blue first-graders choose from the crayon box as a background for a smiling yellow sun. The philosopher Hegel would have loved it: the external world mirroring the clean, happy order of my well-regulated mind.

Beside the sidewalk, a daffodil bloomed.

Not exactly a stop-the-presses moment, is it?

Often, too, aspiring writers will use a single-line paragraph to highlight a punch line. This can work rather well, if it doesn’t occur very often in the text — pull out your hymnals and sing along, readers: any literary trick will lose its efficacy if it’s over-used — AND if the joke is genuinely funny.

Much of the time in manuscripts, alas, it isn’t — at least not hilarious enough to risk enraging Grandma M’s spirit by stopping the narrative short to highlight the quip.

The sky was perfectly clear as I walked home from school that day, the kind of vivid blue first-graders choose from the crayon box as a background for a smiling yellow sun. The philosopher Hegel would have loved it: the external world mirroring the clean, happy order of my well-regulated mind.

My Algebra II teacher would have fallen over dead with astonishment.

Gentle irony does not often a guffaw make, after all. And think about it: if the reader must be notified by a grammatically-questionable paragraph break that a particular line is meant to be funny, doesn’t that very choice indicate a certain doubt that the reader will catch the joke?

Grandma M’s other big objection to Noël’s page 272 — and this pet peeve, too, she is likely to have passed down the generations — would be to the many, many run-on sentences. Like so many aspiring novelists, our Noël favors an anecdotal-style narrative voice, one that echoes the consecutiveness of everyday speech. That can work beautifully in dialogue, where part of the point is for the words captured within the quotation marks to sound like something an actual human being might really say, but in narration, this type of sentence structure gets old fast.

Why might that be, dear readers? Chant it along with me now: structural repetition reads as redundant. Varying the narrative’s sentence structure will render it easier, not to mention more pleasant, to read.

Are some of you former jaw-droppers waving your arms frantically, trying to get my attention? “Okay, Anne,” these sore-jawed folk point out, “I get it: Millicents have disliked textual repetition for decades now. No need to exhume Grandma M’s grandmother to hammer home that point. But I’d had the distinct impression that Millie is a greater stickler for bigger-picture problems than her forebears. Don’t I have more important things to worry about than grammatical perfection when I’m getting ready to slide my manuscript under her nose?”

Well, grammatical perfection is always an asset in a manuscript, ex-jaw-droppers, so I wouldn’t discount it too much in your pre-submission text scan. You are right, however, that present-day Millicents do tend to be weighing a great many more factors than their grandmothers did when deciding whether the manuscript in front of them has publication potential. But not all of those factors involve large-scale questions of marketability and audience-appropriateness; Millicent is also charged with going over the writing with the proverbial fine-toothed comb.

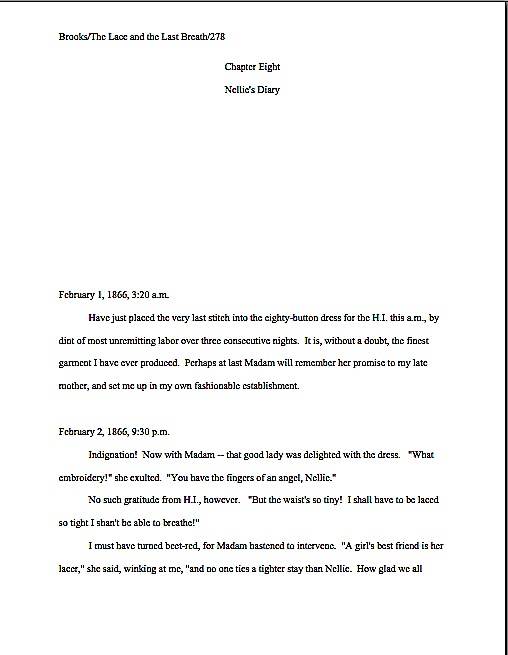

What kinds of manuscript problems might catch on her comb that Grandma M’s would have missed, you ask with fear and trembling? See for yourself — here’s her response on the page we’ve been examining:

I sincerely hope that your first thought upon seeing her much, much higher expectations was not to wish that you’d had the foresight to try to land an agent back in 1960, rather than now. (Although I would not blame you at all if you kicked yourself for not launching your work back in the 1980s, when the home computer was available but not yet ubiquitous, astronomically increasing the number of both queries and submissions Millicent would see in a given week.) True, the competition to land an agent is substantially fiercer now, but it’s also true that a much, much broader range of voices are getting published than in Grandma M’s time.

Back then, if you weren’t a straight, white man from a solid upper-middle class home, Granny expected you at least to have the courtesy to write like one. If you did happen to be a SWMFaSUMCH, you were, of course, perfectly welcome to try to imagine what it was like not to be one, although on the whole, your work would probably be more happily received if you stuck to writing what you knew. And if there was a typo in your manuscript, well, next time, don’t have your wife type it for you.

(You think I’m making that last bit up, don’t you? That’s a quote, something an agent told a rather well-known writer of my acquaintance the 1960s. The latter kept quiet about the fact that he was (a) unmarried at the time and (b) he composed his books on a typewriter.)

Let’s return from that rather interesting flashback, though, and concentrate upon the now. For the purposes of this series on Frankenstein manuscripts, it’s not enough to recognize that literary standards — and thus professional expectations for self-editing — have changed radically over time. It’s not even sufficient to recognize, although I hope it’s occurred to you, that what constituted good writing in your favorite book from 1937 might not be able to make it past Millicent today. (Although if you’re going to use authors from the past as your role models — a practice both Grandma M and I would encourage — you owe it to your career as a writer also to familiarize yourself with the current writing in your book category.)

Just for today, what I would like you to take away from these insights is that each of the editorial viewpoints in these examples would prompt quite different revisions — and in some specific instances, mutually contradictory ones. This is one reason the pros tend not to consider the revision process definitively ended until a book is published and sitting on a shelf: since reading can take place on many levels, so can revision.

Don’t believe me? Okay, clap on your reading glasses and peruse the three widely disparate results conscientious reviser Noël might have produced in response to each of the marked-up pages above. For the first, the one that merely noted the structural, word, and concept repetition, the changes might be as simple as this:

Notice anything different about the text? “Hey, Anne!” I hear some of you burble excitedly. “Despite the fact that Noël has added a couple of paragraph breaks, presumably to make it easier for the reader to differentiate between speech and thought, the text ends up being shorter. He snuck another line of text at the bottom of the page!”

Well-caught, sharp-eyed burblers. A thoughtfully-executed revision to minimize structural redundancy can often both clarify meaning and lop off extraneous text.

I hope you also noticed, though, that while that very specifically-focused revision was quite helpful to the manuscript, it didn’t take care of some of the grammatical gaffes — or, indeed, most of the other problems that would have troubled Grandma M. Let’s take a peek at what our Noël might have done to page 272 after she’s taken her red pen to it. (Hint: you might want to take a magnifying glass to the punctuation.)

Quite different from the first revision, is it not? This time around, the punctuation’s impeccable, but the narration retains some of the redundancy that a modern-day Millicent might deplore.

Millie might also roll her eyes at her grandmother’s winking at instances of the passive voice and the retention of unnecessary tag lines. Indeed, for Noël to revise this page to her specifications, he’s going to have to invest quite a bit more time. Shall we see how he fared?

Not every close-up examination of a single tree, in short, will result in a pruning plan that will yield the same forest. A savvy self-editor will bear that in mind, rather than expecting that any single pass at revision, however sensible, will result in a manuscript that will please every reader.

Wow, that bit about the trees was a tortured analogy; Grandma M would have a tizzy fit. I guess my desk is still insufficiently warmed up. I’ll keep working on it until next time, when it’s back to the ands.

Keep up the good work!