Welcome back to the second installment of Synopsispalooza, Author! Author!’s celebration of the trauma chagrin distressing practical imperative challenging necessity of compressing a deliciously complex, breathtakingly nuanced 400-book into a 5-page summary in standard format. Or whatever length the agent of your dreams or contest of your desires has seen fit to request.

I cannot emphasize that last part strongly enough: although there actually are a couple of standard lengths for synopses in the publishing world, there is no such thing as a standard length for synopses at the query and submission stage. It is your responsibility to check each and every agency’s guidelines to see whether the agent you have chosen to approach prefers a 1-page synopsis, 3, 5, or 8.

Or perhaps 2. Had I mentioned that there was no length standard for querying and submission packets, over and above individual agencies’ expressed preferences?

Or that it is well worth the extra five or ten minutes to double-check whether the agency has a policy on the subject, or if the agent of your dreams once gave a published interview in which she deplored being sent 5-page synopses instead of the 2 1/2 pages for which her heart yearns? As I pointed out in Synopsispalooza I, it never pays to assume that every agency means the same thing by the term synopsis: any given agency may well have a specific reason for wanting something different than all the others.

It’s only polite to respect that preference. And only prudent to do a web search on each agent’s name before you stuff the synopsis you already have on hand into an envelope.

Fortunately, this information is usually quite easy to find: after all, it’s in the agency’s own interest to be clear on the subject. Check the agency’s listing in one of the standard agency guides or its website. (If it has one; a surprisingly hefty percentage still don’t.) And always, always, ALWAYS follow any guidelines set forth in the communication requesting materials.

Yes, I am indeed saying what you think I’m saying: you wouldn’t believe how often, in the heat of post-request excitement, submitters simply disregard the instructions about what they’re supposed to send. Yet another reason for not stopping your life in its tracks to send out requested materials within hours of receiving that yes, eh?

Perhaps less understandably, queriers frequently seem to forget to consult either a guide or the relevant website — or both, since sometimes an agency’s guide listing and the submission guidelines on its website contain different information. When in doubt, go with the website’s restrictions: they’ve probably been updated more recently. Guide listings sometimes remain unchanged for years on end.

A good trick to help avoid the first mistake: do your homework, instead of blithely assuming that every agency must have identical expectations.

They don’t — and they expect writers serious about getting published to be aware of that. If the agency has made the information publicly available, Millicent the agency screener will expect any querier or submitter to be familiar with it. As will her boss.

Seriously, Millicent is not going to consider ignorance a legitimate defense. If your query packet does not include the 4-page synopsis her agency expects, she may well regard that as indicative of a lack of authorial seriousness, or at the very least lack of attention to the details upon which the publishing industry run. Since disregarding stated guidelines is so very common and it’s Millicent’s job to narrow down the competitive field for the very few new client slots her agency has available in any given year, she may well have been instructed to regard a 1-page synopsis, a 5-page synopsis, or no synopsis at all as the agency’s standard rejection triggers.

Why might a demonstrated lack of familiarity with an agency’s querying or submission guidelines — which are, lest I should not yet have made this point sufficiently, likely to differ from other agencies’ — raise red flags for Millicent? Readers who made it through my recent Querypalooza series (or, indeed, this afternoon’s post), feel free to shout out the answer: because a writer who isn’t very good at following directions is inherently more likely to be a time-consuming client than one who shines at producing what s/he is asked to produce.

I hear some annoyed huffing out there, don’t I? “Aren’t you borrowing trouble here, Anne?” some of you ask, arms aggressively akimbo. “Not stuffing the right array of things into a query packet could simply be a matter of having found out about an agent from writers’ forum or one of the many listing websites, rather than having plunked down hard cash for a Herman Guide or tracked down the agency’s website. If agents were REALLY serious about wanting everyone who approaches them to adhere to the guidelines on their sites, wouldn’t they make sure that the same information appears in every conceivable listing, anywhere?”

Well, that might be the case, if agents had infinite time on their hands (they don’t) or if most of the information on fora and secondary sites you mentioned were first-hand (it seldom is). But as I MAY have pointed out once or twice in the past, querying and submission standards are not designed to make life easier for writers; an agency sets its up to meet its own internal needs.

The advantage of relying upon one of the more credible information sources — Jeff Herman’s guide, Guide to Literary Agents, the Publishers’ Marketplace member listings, individual agencies’ websites — is that the information there comes directly from the agencies themselves. Notwithstanding the fact that these sources may occasionally provide mutually contradictory guidelines, you can at least be certain that someone at the agency you are planning to approach has at least heard of them.

Not so with a writers’ forum, an agency listing site, or even — brace yourselves, inveterate conference-goers — what an individual agent might have said in response to a question at a conference. While writers can glean useful information this way, it’s almost invariably second- or third-hand: it may be accurate, but it’s not necessarily what the agent or agency you’re planning to approach would like potential clients to know about them.

So while searching fora and generalist sites can be a good way to come up with a list of agents to query, that shouldn’t be a savvy writer’s only stop. Check out what the agency has to say for itself — because I can tell you now, their Millicent will assume that you are intimately familiar with its stated guidelines, and judge your queries and submissions accordingly.

Besides — and I’m kind of surprised that this little tidbit isn’t more widely known — it tends to drive people who have devoted their lives to the production of books NUTS to encounter the increasingly common attitude that to conduct a 20-second web search IS to have done research. Until fairly recently, conducting research meant actually going to a library or bookstore and looking into a book, a practice that people who sold them for a living really, really condoned.

They miss the days when that was common. They pine for those days.

Trust me on this one: aspiring writers who whine, “But how I was I supposed to know that you wanted a 1-page synopsis rather than the 5-page one the last agency wanted?” when that information is clearly included in a well-respected guide that anyone in North America could have walked into a bookstore and bought do not win friends easily at the average agency.

Unfortunately, from Millicent’s side of the desk, the other problem I mentioned, when queriers get so caught up in the excitement of querying or submission that they just forget to do every step recommended in the guidelines, looks virtually identical to poor research. The over-excited are often penalized as a result.

So how might one avoid that dreadful fate? Here are a few guidelines of my own.

For a query packet:

1. Track down the agency’s SPECIFIC guidelines.

You saw that one coming, didn’t you? Never, ever assume that any given agency will want to see exactly what all the others do.

Yes, even if you heard an agent at a writers’ conference swear up and down that everyone currently practicing her profession does. It’s just not true — unless she was talking about professionalism, attention to detail, courtesy, and submissions in standard manuscript format. (And if you don’t know what that last one is, please see the HOW TO FORMAT A MANUSCRIPT category on the archive list at right before you even consider approaching an agent. Trust me on this one; you’ll be much happier for it at submission time.)

2. Take out a sheet of paper and make a checklist of EVERYTHING those guidelines request.

Don’t trust your memory, especially if you are querying several agents at once. Details can blur under stress.

3. Follow that checklist whilst constructing your query packet.

Again, you probably saw that one coming.

4. Before you seal the query packet (or hit the SEND button), go over your checklist again to make absolutely certain you’ve done everything on it.

Double-checking is the key. If you’re too nervous to feel confident doing this — and many aspiring writers are total nervous wrecks on the eve of querying, so don’t be shy about asking for help — ask your significant other, close friend, obsessive-compulsive sister, or some other detail-oriented person who cares about you to run the final check for you.

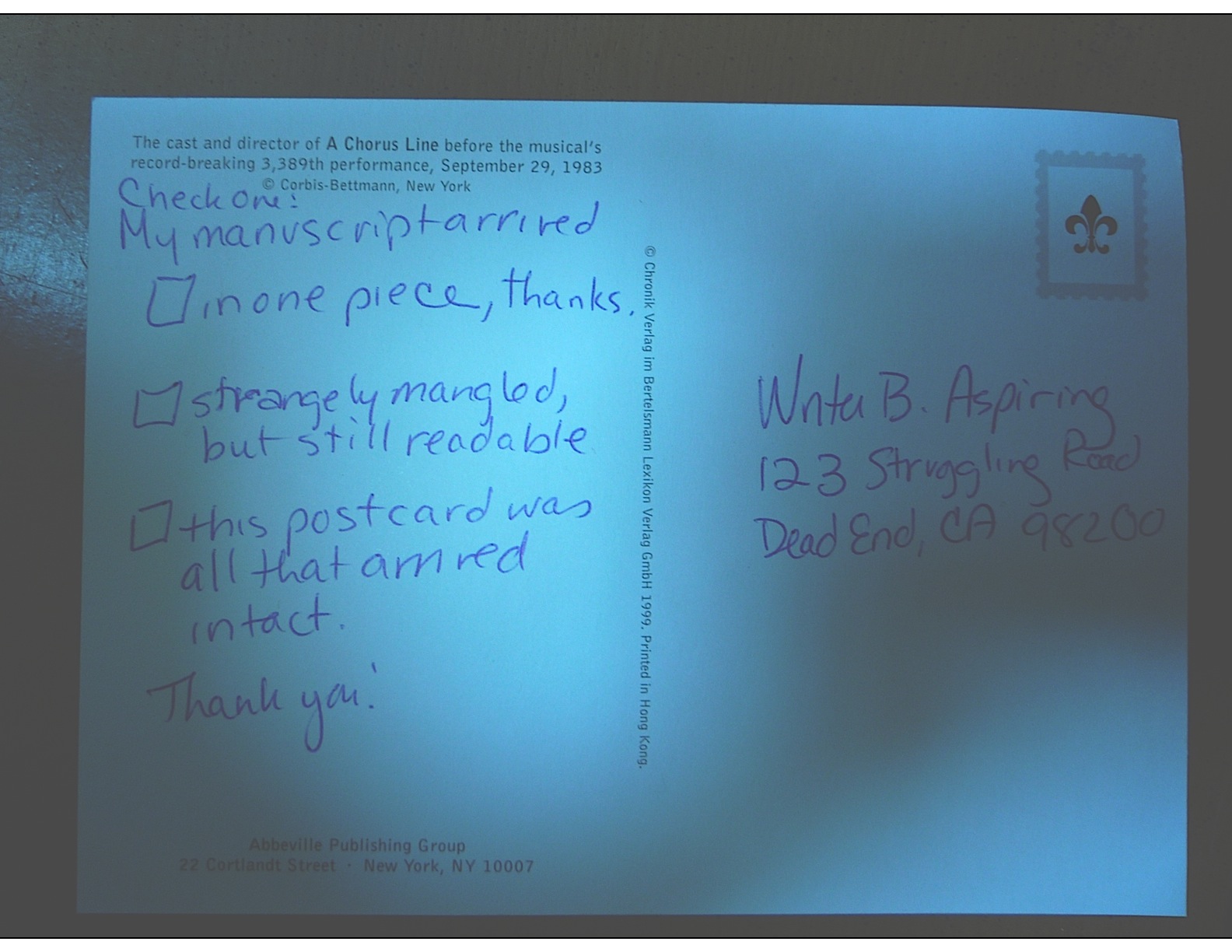

Sounds like overkill, but believe me, every agented and published writer in the world can tell you either a first- or second-hand horror story about the time s/he realized after s/he sealed the envelope/popped it in the mailbox/it was halfway to Manhattan that s/he had omitted some necessary part of the packet. Extra care will both help you sleep better at night and increase your query packet’s chances of charming Millicent.

5. Repeat Steps 1-4 for every agency you query.

Yes, really. It’s a waste of your valuable time to send off a query packet that contains a rejection trigger.

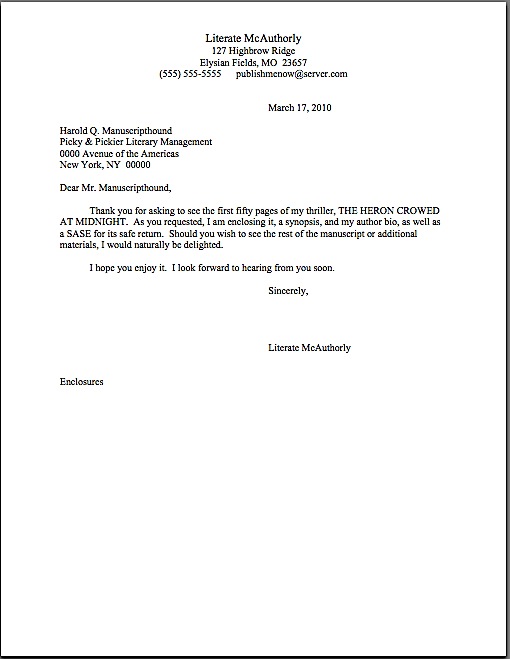

For a submission packet (and I warn you, some of these are going to sound awfully familiar)

1. Read over the request for materials and make a checklist of what you’re being asked to send.

Yes, I mean a physical list, written on actual paper. Don’t tell me that you can do it in your head: many a mis-packed packet has started life with that assertion.

Don’t tell me that you’re in too much of a hurry to do this before you get your manuscript out the door. Must I disturb your slumbers by telling you horror stories about writers who didn’t?

If the request came after a successful pitch, you may have to rely upon your recollections of what’s said, but if the agent asked you in writing for pages, don’t make the EXTREMELY COMMON mistake of just assuming that your first excited reading caught all of the facts. Go over your recollection several times and make a list of what to do.

2. Track down the agency’s SPECIFIC guidelines.

Yes, you should do this even if the requesting agent was very detailed about what s/he wanted. Chances are, the agent of your dreams shares a Millicent with other member agents; if the agency expects submissions to look a certain way, so will the communal Millicent.

3. Have a non-writer go over the request for materials, the agency in question’s guidelines, AND its website, making a separate list of all the agency’s requirements and requests.

No, it’s not sufficient to have someone else double-check your list at the submission stage — this packet is just too important. Have a buddy generate a separate list, to maximize the probability that nothing will be left off.

Why a non-writer, you ask? S/he’s less likely to get swept up in the excitement of the moment. Indeed, if you pick someone obtuse enough, s/he is quite likely to ask with a completely straight face while doing it, “So, when is the book coming out?”

As any agented writer can tell you, the proportion of the general population that doesn’t understand the difference between landing an agent and selling a book to a publishing house is positively depressing. Expect a few of your kith and kin to express actual disappointment when the agent of your dreams offers to represent you: seriously, that fantasy about how really great books magically get picked up by the perfect agent the instant the author types THE END, get sold to a publisher the following day, come out the week after, and land the author on Oprah is astonishingly pervasive.

Hey, I don’t make this stuff up. I just tell you about it, so you won’t get blindsided.

4. Compare and consolidate the two lists.

If there are logical discrepancies, go back and find out which is correct. (Hint: you are more likely to be able to reuse your fact-checker if you don’t do #4 in front of her.)

5. Make absolutely certain that your submission is in standard manuscript format.

I couldn’t resist throwing this in, because so many submissions fall victim to unprofessional formatting. If you have never seen a professional manuscript in person (and no, it does not resemble a published book in several significant respects), please go through the checklist under the THE MANUSCRIPT FORMATTING RULES category at the top of the list at right.

Hey, I put it at the top of the archive list for a reason. Proper formatting honestly is that important to the success of a submission.

I usually add a bunch of disclaimers about how there are many such lists floating around the web, all claiming to be definitive, but it’s tiring to pretend that there isn’t a lot of misinformation out there. I’ve won a major literary contest and sold two books using the guidelines I show on this site; my clients have sold many books and win literary awards relying upon these guidelines. I know agents who refer new clients to my website for these guidelines.

I am, in short, quite confident that my list will work for you. Use it with my blessings.

So as far as I know, there is literally no debate amongst professional book writers about what is required in a manuscript — although to be fair, the standards for short stories and articles are different. For any readers who still throw up their hands and complain that there isn’t a comprehensive set of guidelines out there, all I can suggest is maybe you’re spending a bit too much time surfing and not enough time talking to the pros.

That wasn’t as peevish as it sounded: seriously, if you’re tied up in knots because there isn’t any army out there forcing every single advice-giver to conform to a single set of suggestions, sign up for a writers’ conference or go to a book signing. Pretty much anyone in the industry will be perfectly happy to refer you to a credible source for formatting rules. Perhaps they’ll even send you back here.

But fair warning: almost without exception, they will be miffed at an aspiring writer who complains that an Internet search did not turn up definitive information. As I mentioned above, to book people, that’s simply not doing research.

6. Before you seal the submission packet, dig out the final version of that to-do list and triple-check that you did everything on it.

Again, if you’re not a very detail-oriented person — at least not when you’re extremely nervous — have someone else do the final flight-check. Often, significant others are THRILLED to be helping.

I spy a positive forest of raised hands out there. “But Anne,” all of you hand-raisers shout in chorus, “I’m a trifle confused. Why are you bringing query and submission packet assembly up so pointedly at the beginning of this series on synopsis-writing?”

Oh, hadn’t I mentioned that it’s extremely common for aspiring writers to construct a synopsis and tuck it into every query and submission packet they send out, regardless of what any given agency wants to see? Or that quite a few queriers simply tuck a synopsis into every query envelope?

Whenever you are scanning guidelines, be it for a query packet, submission, or contest entry, pay extra-close attention to length restrictions for synopses. Millicents are known for rejecting a too-long or too-short synopsis on sight. Why? Well, one that is much shorter will make you look as if your story is unable to sustain a longer exposition; if it is much longer, you will look as though you aren’t aware of the standard.

Either way, the results can be fatal to your submission. (See my earlier comment about the desirability of not wasting your own valuable time by assembling self-rejecting submission packets.)

If, as is the case with many agency guidelines, a particular agency does not set a length limit, be grateful: they’re leaving it up to you, not expecting you to read their minds and guess what they consider the industry standard. Use the length that you feel best represents your book, but I would STRONGLY advise not to go over 5 pages, double-spaced.

Yes, yes, I know: some agencies do ask for 8-page synopses. Obviously, if that’s what they ask to see, give it to them. Just don’t assume that any agency that doesn’t ask for a synopsis that long will be happy to see 8 pages fall out of your query packet.

That forest of raised hands just waved in the breeze. Yes? “But Anne, this is all very useful, but I want to know what should go in my synopsis. What works, and what doesn’t?”

Glad you asked, hand-wavers. The answer is not going to sound sexy, I’m afraid, but come closer, and I’ll let you in on the secret:

For fiction, stick to the plot of the novel, including enough vivid detail to make the synopsis interesting to read. Oh, and make sure the writing is impeccable — and, ideally, reflective of the voice of the book.

For nonfiction, begin with a single paragraph about (a) why there is a solid market already available for this book and (b) why your background/research/approach renders you the perfect person to fill that market niche. Then present the book’s argument in a straightforward manner, showing how each chapter will build upon the one before to prove your case as a whole. Give some indication of what evidence you will use to back up your points.

For either, make sure to allot sufficient time to craft a competent, professional synopsis — as well as sufficient buffing time to render it gorgeous. Let’s face it, unlike some of the more — let’s see, how shall I describe them? — fulfilling parts of writing and promoting a book, a synopsis is unlikely to spring into your head fully-formed, like Athene; most writers have to flog the muses quite a bit to produce a synopsis they like.

Too few aspiring writers do, apparently preferring instead to toss together something at the last minute before sending out a submission or contest entry. (Especially a contest entry. I’ve been a judge many times; I know.)

I have my own theories about why otherwise sane and reasonable people might tumble into this particular strategic error. Not being aware that a synopsis would be required seems to be a common reason, as does resentment at having to produce it at all. Or just not being familiar with the rigors of writing one. Regardless, it’s just basic common sense to recognize that synopses are marketing materials, and should be taken as seriously as anything else you write.

Yes, no matter how beautifully-written your book may happen to be. Miss America may be beautiful au naturale, for all any of us know, but you can bet your last pair of socks that at even the earliest stage of going for the title, she takes the time to put on her makeup with care.

On the bright side, since almost everyone just throws a synopsis together, impressing an agent with one actually isn’t as hard as it seems at first blush. Being able to include a couple of stunning visceral details, for instance, is going to make you look like a better writer — almost everyone just summarizes vaguely.

My readers, of course, are far, far too savvy to make that mistake, right? Right? Have half of you fainted?

Even if you are not planning to send out queries or submissions anytime soon (much to those sore-backed muses’ relief), I STRONGLY recommend investing the time in generating and polishing a synopsis BEFORE you are at all likely to need to use it. That way, you will never you find yourself in a position of saying in a pitch meeting, “A 5-page synopsis? Tomorrow? Um, absolutely.”

Yes, it happens. As I mentioned in passing yesterday, it’s actually not all that uncommon for agented and published writers to be asked to provide synopses for books they have not yet written. In some ways, this is easier: when all a writer has in mind is the general outlines of the plot, the details are less distracting.

Actually, if you can bear it — you might want to make sure your heart medication is handy before you finish this sentence –it’s a great idea to pull together a couple of different lengths of synopsis to have on hand, so you are prepared when you reach the querying and submission stages to provide whatever the agent in question likes to see.

Crunching any dry cracker should help the nausea subside.

What lengths might you want to have in stock? Well, a 5-page, certainly, as that is the most common request, and perhaps a 3 as well, if you are planning on entering any literary contests anytime soon. It’s getting more common for agents to request a 1-page synopsis, so you might want to hammer out one of those as well.

I can tell from here that you’ve just tensed up. Take a deep breath. No, I mean a really deep one. This is not as overwhelming a set of tasks as it sounds.

In fact, if you have every done a conference pitch, you probably already have a 1-page synopsis floating around in your mind. (For tips on how to construct one of these babies, please see the aptly-named 2-MINUTE PITCH category at right.)

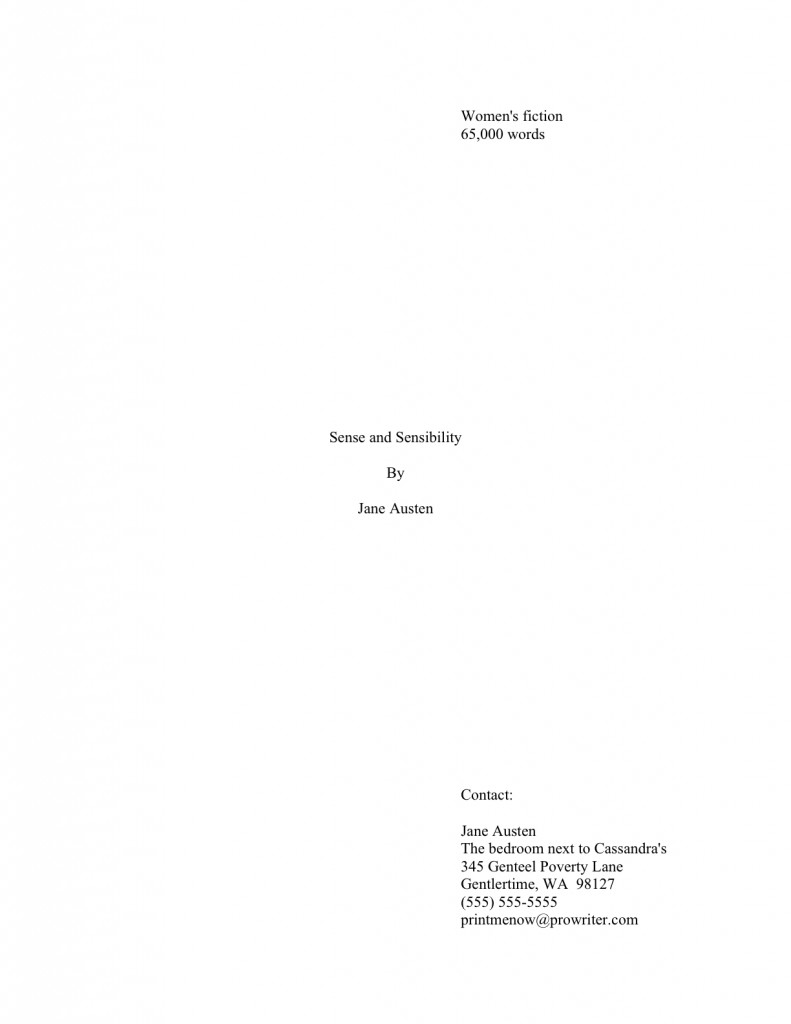

Don’t believe me, oh ye of little faith? Okay, here’s a standard pitch for a novel some of you may have read:

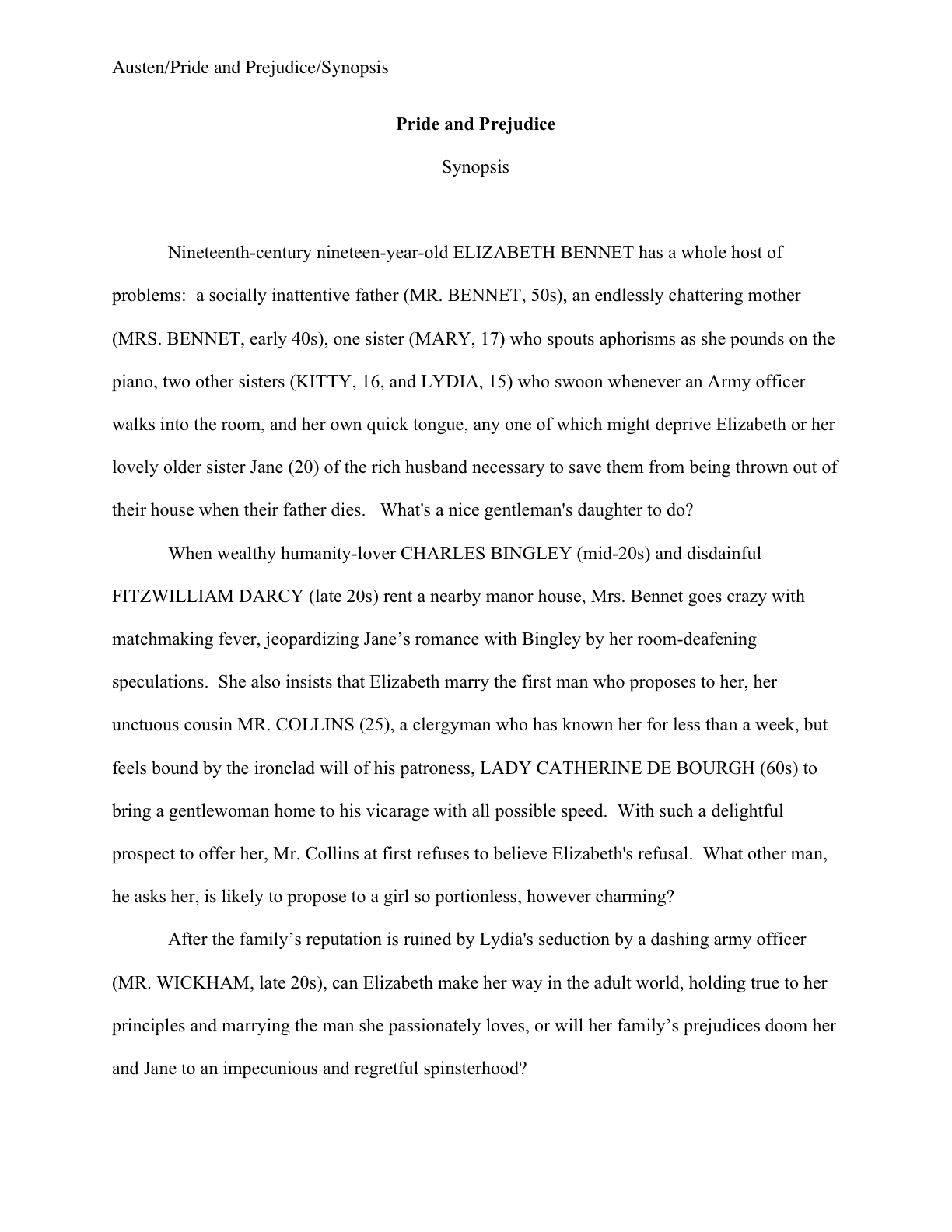

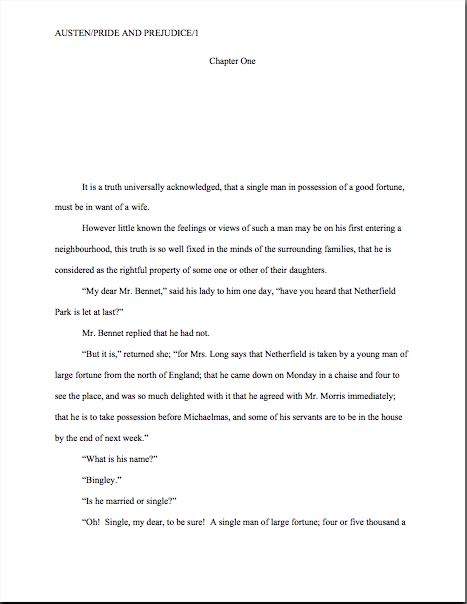

19th-century 19-year-old Elizabeth Bennet has a whole host of problems: a socially inattentive father, an endlessly chattering mother, a sister who spouts aphorisms as she pounds deafeningly on the piano, two other sisters who swoon whenever an Army officer walks into the room, and her own quick tongue, any one of which might deprive Elizabeth or her lovely older sister Jane of the rich husband necessary to save them from being thrown out of their house when their father dies. When wealthy humanity-lover Mr. Bingley and disdainful Mr. Darcy rent a nearby manor house, Elizabeth’s mother goes crazy with matchmaking fever, jeopardizing Jane’s romance with Bingley and insisting that Elizabeth marry the first man who proposes to her, her unctuous cousin Mr. Collins, a clergyman who has known her for less than a week. After the family’s reputation is ruined by her youngest sister’s seduction by a dashing army officer, can Elizabeth make her way in the adult world, holding true to her principles and marrying the man she passionately loves, or will her family’s prejudices doom her and Jane to an impecunious and regretful spinsterhood?

PRIDE AND PREJUDICE, right? This would be a trifle long as an elevator speech — which, by definition, needs to be coughed out in a hurry — but it would work fine in, say, a ten-minute meeting with an agent or editor.

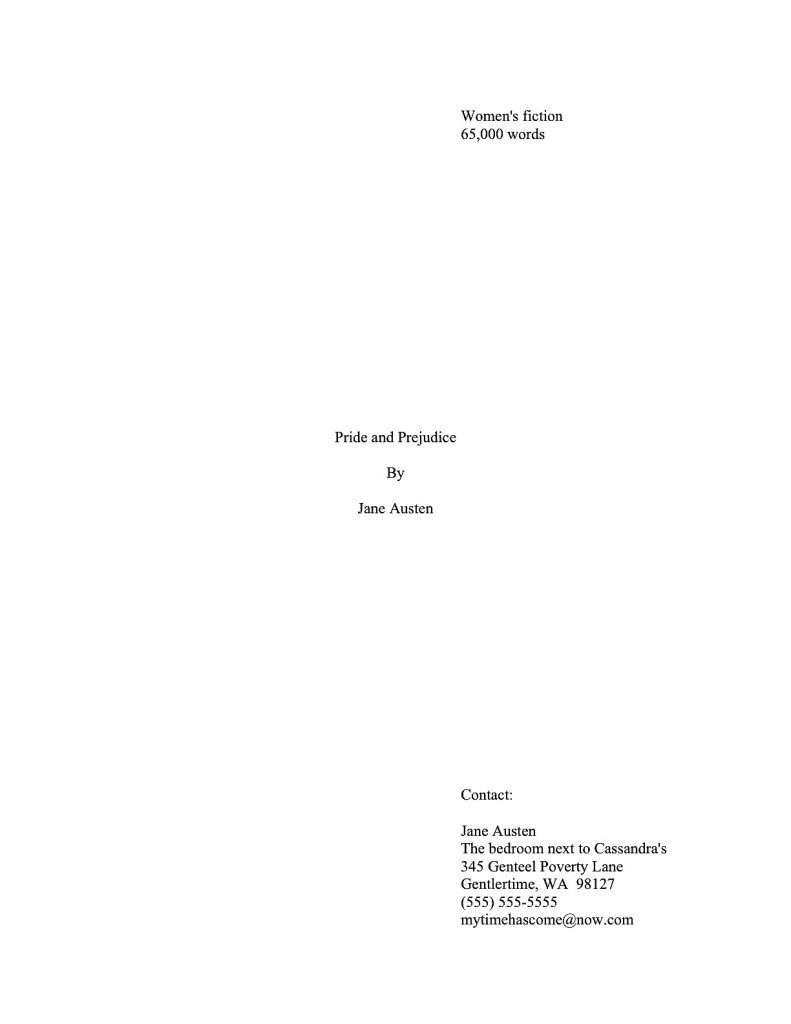

It also, when formatted correctly, works beautifully as a one-page synopsis with only a few minor additions. Don’t believe me? Lookee:

See how simple it is to transform a verbal pitch into a 1-page synopsis? Okay, so if I were Jane (Austen, that is, not Bennet), I MIGHT want to break up some of the sentences a little, particularly that last one that’s a paragraph long, but you have to admit, it works. In fact, I feel a general axiom coming on:

The trick to constructing a 1-page synopsis lies in realizing that it’s not intended to summarize the entire plot, merely to introduce the characters and the premise.

Yes, seriously. As with the descriptive paragraph in a query letter or the summary in a verbal pitch, no sane person seriously expects to see the entire plot of a book summarized in a single page. It’s a teaser, and should be treated as such.

Doesn’t that make more sense than driving yourself batty, trying to cram your entire storyline or argument into 22 lines? Or trying to shrink that 5-page synopsis you have already written down to 1?

Yes, yes, I know: even with reduced expectations, composing a 1-page synopsis is still a tall order. That’s why you’re going to want to set aside some serious time to write it — and don’t forget that the synopsis is every bit as much an indication of your writing skill as the actual chapters that you are submitting. (Where have I heard that before?)

Because, really, don’t you want YOURS to be the one that justified Millicent’s heavily-tried faith that SOMEBODY out there can tell a good story in 3 – 5 pages? Or — gulp! — 1?

Don’t worry; you can do this. There are more rabbits in that hat, and the muses are used to working overtime on good writers’ behalves.

Just don’t expect Athene to come leaping out of your head on your first try: learning how to do this takes time. Keep up the good work!

PS: Please do not panic when you see that the post immediately below this one is not in fact about synopses: in an effort to make up for some missed posting days last week, I shall be inserting posts analyzing the winning entries of theAuthor! Author! Great First Page Made Even Better contest between the next few Synopsispalooza posts. If you are looking for the previous Synopsispalooza post, but are too lazy enslaved to repetitive strain injuries time-strapped to scroll, you’ll find it just one click away here.

No matter how many pages or extra materials you were asked to send, do remember to read your submission packet IN ITS ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD before you seal that envelope. Lest we forget, everything you send to an agency is a writing sample: impeccable grammar, punctuation, and printing, please.

No matter how many pages or extra materials you were asked to send, do remember to read your submission packet IN ITS ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD before you seal that envelope. Lest we forget, everything you send to an agency is a writing sample: impeccable grammar, punctuation, and printing, please.

No matter how many pages or extra materials you were asked to send, do remember to read your submission packet IN ITS ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD before you seal that envelope. Lest we forget, everything you send to an agency is a writing sample: impeccable grammar, punctuation, and printing, please.

No matter how many pages or extra materials you were asked to send, do remember to read your submission packet IN ITS ENTIRETY, IN HARD COPY, and OUT LOUD before you seal that envelope. Lest we forget, everything you send to an agency is a writing sample: impeccable grammar, punctuation, and printing, please.