For the last couple of days, I have been urging those of you who received requests to submit all or part of your manuscripts to an agent or editor more than a season ago to take some swift steps to get them out the door as soon as possible. And I could feel a great many of you tensing up more each time I mentioned it.

I understand the hesitancy, believe me. Naturally, you want your work to be in tip-top shape before you slide it under a hyper-critical reader’s nose — lest we forget, agency screeners who are not hyper-critical tend to lose their jobs with a rapidity that would make a cheetah’s head spin — but once you’ve shifted from your summer to winter wardrobe without popping that those pages requested when your Fourth of July decorations were up into the mail, it’s easy to keep sliding down the slippery slope toward never sending it out at all.

Whoa, Nelly, that was a long sentence! Henry James would be so proud. But you get my point.

I also understand the temptation to put off those last few revisions until you have some serious time to devote to them — like, say, the upcoming Thanksgiving long weekend or a Christmas vacation. Even if we disregard for the moment the distinct possibility that days off from work during family-oriented holidays might get filled up with, say, family activities, the wait-until-I-have-time strategy tends to backfire.

Why? Well, for many aspiring writers, holding on to requested materials too long allows an increasing sense of shortcoming to develop. Over time, as-yet-to-be-done revisions loom larger and larger in the mind, necessitating (the writer thinks) setting aside more and more future time to take care of them. So what started out as a few hours to carve out of a busy schedule transmogrifies into a few days, or even a few weeks.

Hands up, if you habitually can take that much unbroken time off work at a stretch. Working Americans typically cannot.

What I’m about to say may make working writers everywhere break into gales of hysterical laughter, but sometimes, a deadline is a writer’s friend. When you have too long to consider how to polish a manuscript, the process can easily mushroom. While giving serious thought to manuscript changes is good, extended fretting prior to sitting down and making those alterations can easily start to color the editing process — rendering it MORE difficult to make those last-minute changes as time goes on, not less.

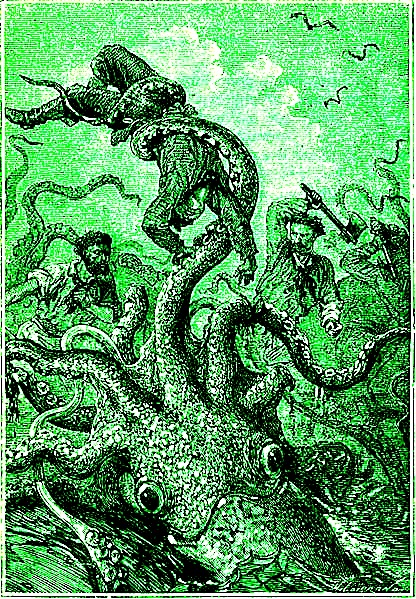

Even if task escalation does not assault your project like the giant squid in the photo above (native to the cold, murky waters bordering Seattle!), the demons of self-doubt just love a delayed deadline. It allows them so much more time to apply their pitchforks to writers’ latent insecurities.

“If my pitch/query were really so wonderful,” a nasty little voice starts to murmur in writers’ heads, “why hasn’t that agent followed up with me, to see why I haven’t sent it? Maybe s/he was just being nice, and didn’t want to see it at all.”

Little voice, I can tell you with absolute certainty why that agent or editor hasn’t followed up: BECAUSE THE INDUSTRY DOESN’T WORK THAT WAY. It has exactly nothing to do with what the requester did or did not think of you or your book, then or now. Period.

You wanna know why I can say that with such assurance? Because at the point your manuscript arrives for an agent’s perusal, his office looks like this:

And not, as aspiring writers worldwide would prefer to believe, like this:

Yes, Virginia, all of those fuzzy piles in the first photo are precisely what you think they are: manuscripts waiting to be read. Trust me on this one: the agent who requested your manuscript seven months ago is not currently staring listlessly out her office window, wishing she had something to read. She’s been keeping herself occupied with those thousands of pages already blocking her way to her filing cabinet.

Which is why a writer who is waiting, Sally Field-like, to be told that the agent likes her, really, really likes her before submitting is in for a vigil that would make Penelope think that Odysseus didn’t take all that long to meander back from the Trojan War.

I hate to disillusion anybody (although admittedly, that does seem to be a large part of what I do in this forum), but unless you are already a celebrity in your own right, no agent in the biz is going to take the initiative to ask a second time about ANY book that she has already requested, no matter how marvelous the premise or how much she liked the writer — or even how great the query letter was.

And before you even form the thought completely: no, Virginia, there ISN’T a pitch you could have given or a query you could have sent that would have convinced her to make YOUR book her sole lifetime exception to this rule. The Archangel Gabriel could have descended in a pillar of flame three months ago to pitch his concept for a cozy mystery, and it still would not occur to the slightly singed agent who heard the pitch to send a follow-up skyward now to find out why the manuscript has never arrived.

Gabriel got sidetracked at work, apparently. I suspect it’s due to all those manuscripts he has to read.

So while that agent who legitimately fell in love with your pitch five months ago might well bemoan over cocktails with her friends that great book concept that the flaky writer never finished writing — which is, incidentally, what she will probably conclude happened — but she is far more likely to take up being a human fly, scaling the skyscrapers of Manhattan on her lunch hour on a daily basis than to pick up the phone and call you to ask for your manuscript again.

Sorry. If I ran the universe, she would start calling after three weeks, overflowing with helpful hints and encouraging words. She would also order your boss to give you paid time off to finish polishing, bring you chicken soup when you are feeling under the weather, and scatter joy and pixie dust wherever she tread.

But as I believe I have pointed out before, due to some insane bureaucratic error at the cosmic level, I do not, evidently, rule the universe. Will somebody look into that, please?

By the same token, however, the agently expectation that the writer should be the one to take the initiative to reestablish contact after an extended lull can be freeing to someone caught in a SIOA-avoidance spiral. If you have not yet sent requested materials, it’s very, very unlikely that the requesting agent is angry — or will be angry when the material arrives later than she originally expected it.

What makes me so sure of that? Because agents learn pretty quickly that holding their breath, waiting for requested manuscripts to arrive, would equal a lifetime of turning many shades of blue. SIOA-avoidance is awfully common, after all.

Oh, didn’t you know that? Hadn’t I mentioned that about 70% of requested materials never show up on the agent’s desk at all?

So a writer who has hesitated for six months before sending in requested materials can mail them off with relative confidence that a tongue-lashing is not imminent. 99.998% of the time, the agent in question’s first response upon receiving the envelope WON’T be: “Oh, finally. I asked for this MONTHS ago. Well, too late now…”

I hate to break this to everyone’s egos, but in all probability, there won’t be any commentary upon its late arrival at all — or, at any rate, no commentary that will make its way back to you. But that is a subject best left for a later post.

For now, suffice it to say that even if it has been four or five months since an agent requested your manuscript, I would still strongly advise sending it out anyway — with perhaps a brief apology included in your “Thank you so much for requesting this material” cover letter. (You HAVE been sending polite cover letters with your submissions, right?) And I would recommend this not only because the agent might pick it up, but because it’s important to break the SIOA-avoidance pattern before it becomes habitual.

Think about it: once you have put your ego on the line enough to pitch or query a book and then talked yourself out of sending it, do you honestly think either the pitch/query or submission processes are going to be emotionally easier the next time around?

For most aspiring writers, the opposite is true: after one round of SIOA-avoidance, working up the gumption to send out requested materials, or even query again, is considerably harder, because the last time set up the possibility of not following through as a viable option. The psyche already knows that nothing terrible will happen in the short term if the writer, to use the vernacular, chickens out.

Yet in the long term, something terrible can and often does occur: a good book doesn’t find the right agent to represent it, nor the right editor to publish it, because its writer didn’t want to risk sending it out until it was 100% perfect.

Whatever that means when we’re talking about a work of art.

Please don’t take any of this personally, should you happen to be in the midst of a SOIA-avoidance spiral. It is a legitimate occupational hazard in our profession: I know literally hundreds of good writers who have been in pitch/reedit/talk self out of submitting yet/reedit/pitch again at next year’s conference cycles for years. One meets them at conferences all over North America, alas: always pitching, always revising, never submitting.

Please, I implore you, do not set up such a pattern in your writing life. SIOA. And if you have already fallen into SIOA-avoidance, break free the only way that is truly effective: SIOA now.

As in stop reading this and start spell-checking.

I can tell that all of this begging is not flying with some of you. “But Anne,” the recalcitrant protest (blogging gives one very sensitive ears, capable of discerning the dimmest of cries out there in the ether), “what if I’ve been feeling ambivalent toward sending my manuscript out because there is actually something seriously wrong with it? Shouldn’t I listen to my gut, and hang onto my book until I feel really good about showing it to the pros?”

Yes and no, reluctant submitters; if a manuscript is indeed deeply flawed, I would be the last person on earth (although I know other professional readers who would arm-wrestle me for the title) who would advise the writer against taking serious steps to rectify it. Joining a first-rate writers’ group, for instance, or hiring a freelance editor to whip it into shape. Almost any such steps, however, are going to take some time.

Before anyone screams, “AHA! Then I shouldn’t send it out yet!” let me hasten to add: your garden-variety agent tends to assume that a conscientious writer will have implemented some kind of extensive long-term strategy to improve a manuscript before querying or pitching it, not after.

So if you are already certain that your manuscript is free of spelling and grammatical errors and formatted correctly (if you’re not absolutely positive about the latter, please see the HOW TO FORMAT A MANUSCRIPT category on the archive list at the bottom-right side of this page), go ahead and send it now anyway, just in case your sense of shortcoming is misplaced, AND take steps to improve it thereafter. It might be accepted, you know.

And even if it isn’t, there’s nothing to prevent you from querying the agent again in a year or two with a new draft, gleaming with all of that additional polishing.

(For the benefit of those of you who have heard that apparently immortal writers’ conference circuit rumor: no, agencies do NOT keep such meticulous records that in 2012, the Millicent du jour will take one glance at a query, go rushing to a database, and say, “Oh, God, THIS book again; we saw another version of it in the autumn of 2009. I need to reject it instantly.” Although she might start to think it if you submitted the same manuscript three times within the same year.)

Again, PLEASE do not be hard on yourself if you wake up in a cold sweat tomorrow morning, screaming, “Wait — she was talking about ME! I’m in SIOA-avoidance mode!” (For your ease in waking your bedmates, I pronounce it SEE-OH-AH.) The important thing is to recognize it when it is happening — and to take steps to break the pattern before it solidifies.

Whatever you do, don’t panic — SIOA-avoidance can be overcome. Before I’m done with this topic, I’ll give you some pointers on how to phrase a cover letter to accompany a much-delayed submission without sounding like you’re groveling or requiring you to pretend that you’ve been in a coma for the last six months, unable to type.

You can move on with dignity, I promise. No one’s going to scream at you, and no one is going to laugh at you, but your book will be grateful. I promise.

Keep up the good work!