Welcome back to my refresher course on standard format for manuscripts. Since I know that many of you are scrambling like crazy, trying to get submissions out the door before the dreaded holiday publishing world malaise sets in, or scrambling like crazy to get submissions in shape in anticipation of the moment that the agent of your dreams answers affirmatively to the query letter that you are sending out before the annual malaise, or are scrambling like crazy after yesterday’s post, since you hadn’t realized that there WAS a standard format for manuscript submissions, I wanted to take another run at it.

My apologies for revisiting this to those of you who are already formatting your manuscripts perfectly — but unless you are ABSOLUTELY POSITIVE that you are, you might want to sit in on this series, too.

If you’re not willing to do it for your own sake, do it for mine. It breaks my heart to see good writers, even great ones, making the same formatting mistakes year in and year out, getting rejected for reasons that are apparent to professional readers from halfway across the room.

And no, Virginia, I’m not kidding about the halfway across the room part.

Although it pains me to confess it, how a manuscript looks can have an IMMENSE impact upon how an agent, editor, contest judge, or even a book doctor like me will respond to it. Talent, style, and originality count, of course, but in order to notice any of those, a reader has to approach the page with a willingness to be wowed.

That willingness can wilt rapidly in the face of incorrect formatting — which isn’t, in response to what half of you just thought, the result of mere market-minded shallowness on the part of the reader. Reading manuscripts for a living makes deviations from standard format leap out at one. As do spelling and grammatical errors, phrase repetition, clichés, and all of the many notorious agents’ pet peeves. (If you think I’m exaggerating, check out some of the lulus under the FIRST PAGES AGENTS DISLIKE and AGENCY SCREENERS’ PET PEEVES OF THE NOTORIOUS VARIETY categories on the list at right.)

The sheer repetition of mistakes across manuscripts means that professional readers tend to focus on technical details when scanning the work of a new writer. Because all professional manuscripts are formatted identically, it’s INCREDIBLY obvious when one isn’t.

This is a really, really good thing to know BEFORE you submit to an agent or editor: even if 99.9% of the format is right, that .1% deviation actually will distract a professional reader from even the most beautiful writing.

And that’s not merely a matter of being obsessive-compulsive (although truth compels me to say that in this line of work, OCD is hardly an occupational drawback) — as I shall be showing you later on in this series, to someone who reads manuscripts for a living, deviations from standard format might as well be printed in blood-red ink.

So while it may seem tedious, annoying, or just a whole lot of work to go through your submissions with the proverbial fine-toothed comb in order to weed out this kind of distraction.

I hear those of you who have spent years slaving over your craft groaning out there — believe me, I sympathize. I fully realize that many of the tiny-but-pervasive changes I am about to suggest that you make to your manuscript are going to be irksome to implement. Reformatting a manuscript is time-consuming and tedious – and I would be the first to admit that at first, some of these rules can seem arbitrary.

At least on their faces, that is.

Speaking as someone who reads manuscripts for a living, I can let you in on a little secret: quite a few of these restrictions remain beloved of the industry even in the age of electronic submissions because they render a manuscript a heck of a lot easier to edit in hard copy — still the norm, incidentally. As I will show later in this series, a lot of these rules exist for completely practical purposes — designed, for instance, to maximize white space in which the editor may scrawl trenchant comments like, “Wait, wasn’t the protagonist’s sister named Maeve in the last chapter? Why is she Belinda here?”

As I said above, this is one line of work where a touch of compulsiveness is a positive boon. Treat this brain pattern with the respect it deserves.

And treat your own writing with the respect it deserves by taking the time to present it professionally. Obviously, competition to land an agent and get published is very intense, but if you’re going to get rejected, wouldn’t you rather it be because an agent or editor legitimately disagreed with your writing choices, instead of because you didn’t follow the rules?

Or, more commonly, because you weren’t aware of them?

Frankly, it’s bad for writers everywhere that these rules are not more widely known. Okay, so it keeps freelance editors like me in business, but it has created a submission environment where poor formatting is generally considered a warning sign of poor WRITING to come.

By Millicent the agency screener, her cousin Maury the editorial assistant, and their aunt Mehitabel the contest judge, in any case.

And that drives conscientious aspiring writers, the ones who — like you, perhaps — have invested considerable time and sweat in learning something about the trade, completely batty. Because, like so much generalized criticism, the fine folks who take the advice most seriously tend to be the ones who need it least, I know that there are thousands of you out there who stay up nights, compulsively going over their manuscripts for the 147th time, trying to ferret out that one last bit of less-than-professional presentation.

Bless your heart, if you’re one of those. You’re helping raise aspiring writers’ collective reputation within the industry.

One quick caveat before we get started today: the standard format restrictions I’m listing here are for BOOK submissions, not for short stories, poetry, journalistic articles, academic articles, or indeed any other form of writing. For the guidelines for these, you may — and should — seek elsewhere.

Let me repeat that, because it’s important: the guidelines in this series are for BOOK manuscripts and proposals, and thus should not be applied to other kinds of writing. Similarly, the standards applicable to magazine articles, short stories, dissertations, etc. should not be applied to book proposals and manuscripts.

Which is a gentle way of saying that the formatting and grammatical choices you see in newspapers will not necessarily work in manuscripts. AP style is different from standard format in several important respects, not the least being that in standard format (as in other formal presentations in the English language), the first letter of the first word after a colon should NOT be capitalized, since technically, it’s not the beginning of a new sentence.

I don’t know who introduced the convention of post-colon capitalization, but believe me, those of us who read the submissions of aspiring book writers for a living have mentally consigned that language subversive to a pit of hell that would make even Dante avert his eyes in horror.

Everyone clear on that? Good, because — are you sitting down, lovers of newspapers? — embracing journalistic conventions like the post-colon capital and writing out only numbers under ten (see below) will just look like mistakes to Millicent and her ilk on the submission page.

And no, there is no court of appeal for such decisions. So if you were planning to cry out, “But that’s the way USA TODAY does it!” save your breath.

Unfortunately, although my aforementioned heart aches for those of you who intended to protest, “But how on earth is an aspiring writer to KNOW that the standards are different?” this is a cry that is going to fall on deaf ears as well. Which annoys me, frankly.

The sad fact is, submitters rejected for purely technical reasosn are almost never aware of it. With few exceptions, the rejecters will not even take the time to scrawl, “Take a formatting class!” or “Next time, spell-check!” on the returned manuscript. If a writer is truly talented, they figure, she’ll mend her ways and try again.

Call me zany, but I’d like to speed up that learning curve. I think that the way-mending might go a TRIFLE faster if the writer knew that the manuscript was broken

It’s not as though the strictures of standard format are state secrets, after all. To recap from yesterday:

(1) All manuscripts should be printed or typed in black ink and double-spaced, with one-inch margins around all edges of the page, on 20-lb or better white paper.

(2) All manuscripts should be printed on ONE side of the page and unbound in any way.

(3) The text should be left-justified, NOT block-justified. By definition, manuscripts should NOT resemble published books in this respect.

(4) The preferred typefaces are 12-point Times, Times New Roman, Courier, or Courier New — unless you’re writing screenplays, in which case you may only use Courier. For book manuscripts, pick one (and ONLY one) and use it consistently throughout your entire submission packet.

Everyone clear on those? PLEASE pipe up with questions, if not. In the meantime, let’s move on.

(5) The ENTIRE manuscript should be in the same font and size. Industry standard is 12-point.

No exceptions. I hate to be the one to break it to you, but there’s a term in the industry for title pages with 24-point fonts, fancy typefaces, and illustrations.

It’s “high school book report.” Need I say more?

The font rule also applies to your title page, incidentally, where almost everyone gets a little wacky the first time out. No matter how cool your desired typeface looks, or how great the title page looks with 14-point type.

No pictures or symbols here, either, please. Just the facts. (If you don’t know how to format a title page professionally, please see the TITLE PAGE category on the list at right.)

(6) Do NOT use boldface anywhere in the manuscript BUT on the title page — and not even there, necessarily.

Yes, you read that correctly: you may place your title in boldface on the title page, if you like, but that’s it. Nothing else in the manuscript should be bolded.

This rule is a throwback to the old typewriter days, where only very fancy machines indeed could darken selected type. Historically, using bold in-text is considered a bit tacky for the same reason that wearing white shoes before Memorial Day is in certain circles: it’s a subtle display of wealth.

(You didn’t think all of those white shoes the Victorians wore cleaned themselves, did you? Shiny white shoes equaled scads of busily-polishing staff.)

(7) EVERY page in the manuscript should be numbered EXCEPT the title page.

Violating this rule will result in instantaneous rejection virtually everywhere. Number those pages if it’s the last thing you do.

Few non-felonious offenses irk the professional manuscript reader (including yours truly, if I’m honest about it) more than an unnumbered submission — it ranks right up there on their rudeness scale with assault, arson, and beginning a query letter with, “Dear Agent.”

Why? Gravity, my friends, gravity. What goes up tends to come down — and if the object in question happens to be an unbound stack of paper…

Did that seem like an abstract metaphor? Not at all. Picture, if you will, two manuscript-bearing interns colliding in an agency hallway.

You may giggle, but anyone who has ever worked with submissions has first-hand experience of this, as well as what comes next: after the blizzard of flying papers dies down, and the two combatants rehash that old Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup commercial’s dialogue (“You got romance novel in my literary fiction!” “You got literary fiction in my romance novel!”), what needs to happen?

Yup. Some luckless soul has to put all of those pages back in the proper order. Think about it: just how much more irksome is that task going to be if the pages are not numbered?

Number your pages. Trust me, it is far, far, FAR easier to toss the entire thing into the reject pile than to spend the hours required to guess which bite-sized piece of storyline belongs before which.

FYI, the first page of the text proper is page 1 of the text, not the title page, and should be numbered as such. If your opus has an introduction or preface, the first page of THAT is page 1, not the first page of chapter 1.

Why, you ask? Long-time readers, pull out your hymnals: BECAUSE A MANUSCRIPT SHOULD NOT LOOK IDENTICAL TO A PUBLISHED BOOK.

To run over the other most popular choices for pages to mislabel as page 1: manuscripts do not contain tables of contents, so there should be no question of pagination for that. Also, epigraphs — those quotations from other authors’ books so dear to the hearts of writers everywhere — should not appear on their own page in a manuscript, as they sometimes do in published books; if you feel you must include one (considering that 99.9999% of the time, Millicent will just skip over it), include it between the chapter title and text on page 1.

If that last sentence left your head in a whirl, don’t worry — I’ll show you how to format epigraphs properly later in this series. (Yes, including some discussion of that cryptic comment about Millicent.)

(8) Each page of the manuscript (other than the title page) should have a standard slug line in the header. The page number should appear in the slug line, not anywhere else on the page.

Most writing handbooks and courses tend to be a trifle vague about this particular requirement, so allow me to define the relevant terms: a well-constructed slug line includes the author’s last name, book title, and page number, to deal with that intern-collision problem I mentioned earlier. (The slug line allows the aforementioned luckless individual to tell the romance novel from the literary fiction.) And the header, for those of you who have not yet surrendered to Microsoft Word’s lexicon, is the 1-inch margin at the top of each page.

Including the slug line means that every page of the manuscript has the author’s name on it — a great idea, should you, say, want an agent or editor to be able to contact you after s/he’s fallen in love with it.

The slug line should appear in the upper left-hand margin (although no one will sue you if you put it in the upper right-hand margin, left is the time-honored location) of every page of the text EXCEPT the title page (which should have nothing in the header or footer at all).

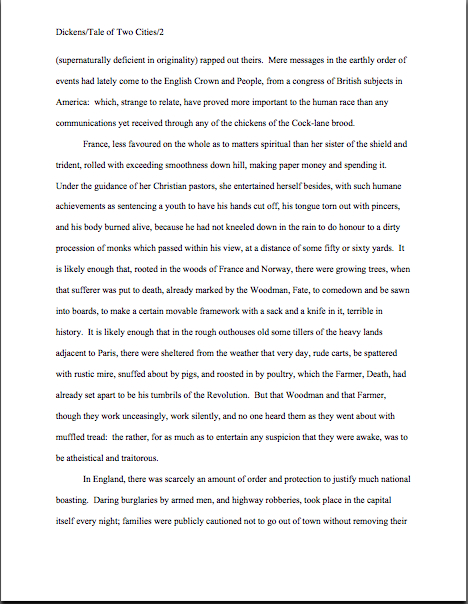

Traditionally, the slug line appears all in capital letters, but it’s not strictly necessary. Being something of a traditionalist, the third page of my memoir has a slug line that looks like this:

MINI/A FAMILY DARKLY/3

Since the ONLY place a page number should appear on a page of text is in the slug line, if you are in the habit of placing numbers wacky places like the middle of the footer, do be aware that it does not look strictly professional to, well, professionals. Double-check that your word processing program is not automatically adding extraneous page markers.

Do not, I beg of you, yield like so many aspiring writers to the insidious temptation add little stylistic bells and whistles to the slug line, to tart it up. Page numbers should not have dashes on either side of them, be in italics or bold, or be preceded by the word “page.”

If that news strikes you as a disappointing barrier to your self-expression, remember, professional readers do not regard formatting choices as conveyers of personal style. The point here is not to make your slug line stand out for its innovative style, but for your manuscript’s pages to look exactly like every other professional writer’s.

And yes, I AM going to keep making that point over and over until you are murmuring it in your sleep. Why do you ask?

If you have a subtitle, don’t include it in the slug line — and if you have a very long title, feel free to abbreviate, to keep the slug line from running all the way across the top of the page. The goal here is to identify the manuscript at a glance, not to reproduce the entire book jacket.

Why not? Well, technically, a slug line should be 30 spaces or less, but there’s no need to stress about that in the computer age. A slug, you see, is the old-fashioned printer’s term for a pre-set chunk of, you guessed it, 30 spaces of type.)

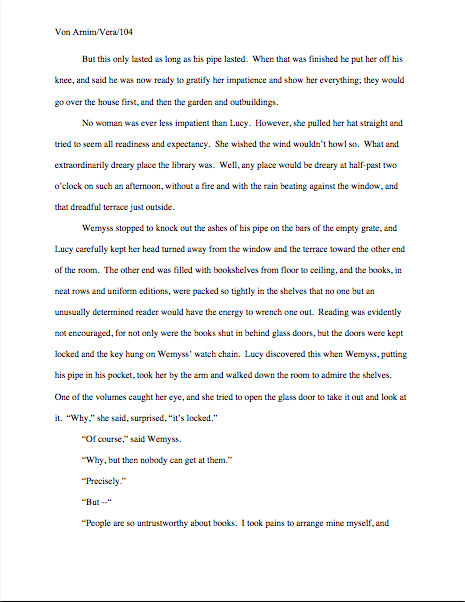

Keep it brief. For instance. my agent is currently circulating a novel of mine entitled THE BUDDHA IN THE HOT TUB — 26 characters, counting spaces. Since my last name is quite short, I could get away with putting it all in the slug line, to look like this:

MINI/THE BUDDHA IN THE HOT TUB/1

If, however, my last name were something more complicated, such as Montenegro-Copperfield — 22 characters all by itself, including dash — I might well feel compelled to abbreviate:

MONTENEGRO-COPPERFIELD/BUDDHA/1

(9) The first page of each chapter should begin a third of the way down the page, with the chapter title appearing on the FIRST line of the page, NOT on the line immediately above where the text begins.

That’s twelve single-spaced lines, incidentally. The chapter name (or merely “Chapter One”) may appear on the FIRST line of the first page — not on the last line before the text, as so many writers mistakenly do. The chapter title or number should be centered, and it should NOT be in boldface or underlined.

Don’t panic if you’re having trouble visualizing this — I’ll be giving concrete examples of what the first page of a chapter should look like later in this series.

Why shouldn’t the title appear immediately above the text, as one so often sees? Because that’s where the title of a SHORT STORY lives, not a book’s.

Very frequently, agents, editors and contest judges are presented with improperly-formatted first pages that include the title of the book, “by Author’s Name,” and/or the writer’s contact information in the space above the text. This is classic rookie mistake. To professional eyes, a manuscript that includes any of this information on the first page of the manuscript (other than in the slug line, of course) seems term paper-ish.

So where does all of that necessary contact information go, you ask? Read on.

(10) Contact information for the author belongs on the title page, NOT on page 1.

This is one of the main differences between a short story submission (say, to a literary journal) and a novel submission. To submit a manuscript — or contest entry, for that matter — with this information on page 1 is roughly the equivalent of taking a great big red marker and scrawling, “I don’t know much about the business of publishing,” across it.

Just don’t do it.

“But wait,” I hear some of you out there murmuring, “I need a title page? Since when?”

Funny you should mention that, because…

(11) Every submission should include a title page, even partial manuscripts.

This one seems to come as a surprise to a LOT of aspiring writers. You should ALWAYS include a title page with ANY submission of ANY length, including contest entries and the chapters you send after the agent has fallen in love with your first 50 pages.

Why, you ask? Because it is genuinely unheard-of for a professional manuscript not to have a title page: literally every manuscript that any agent in North America sends to any editor will include one. Yet, astonishingly, 95% of writers submitting to agencies seem to be unaware that including it is industry standard.

On the bright side, this means that if you are industry-savvy enough to include a professionally-formatted title page with your work, your submission automatically looks like a top percentile ranker to professional eyes from the moment it’s pulled out of the envelope. It’s never too early to make a good first impression, right?

If you do not know how to format a proper title page (and yes, Virginia, there IS a special format for it, too), please see the TITLE PAGE category at right. Or wait a few days until I cover it later in this series. It’s entirely up to you.

Before anyone asks: omitting a title page is too common a mistake to be an automatic deal-breaker for most Millicents; she’s almost certainly not going to toss out a submission ONLY because it has a properly-formatted title page or none at all. And yes, one does occasionally run into an agent at a conference or one blogging online who says she doesn’t care one way or the other about whether a submission has a title page resting on top at all.

Bully for them for being so open-minded, but as I point out roughly 127,342 times per year in this forum, how can you be sure that the person deciding whether to pass your submission upstairs or reject it ISN’T a stickler for professionalism?

I sense some shoulders sagging at the very notion of all the work it’s going to be to alter your pages before you send them out. Please believe me when I tell you that, as tedious as it is to change these things in your manuscript now, by the time you’re on your third or fourth book, it will be second nature to you.

Why, I’ll bet that the next time you sit down to begin a new writing project, you will automatically format it correctly. Think of all of the time THAT will save you down the line.

More importantly, if you embrace these standards, any submissions you might happen to send out in the near future will look like the work of a pro. Again, call me zany, but I would rather see an agent or editor evaluate your book on the basis of your writing and your story, not your formatting knowledge.

I’m funny that way.

Next time, I’m going to finish going through the rules, so we may move on swiftly to concrete examples of what all of this formatting looks like in practice. Keep up the good work!