My, I’ve been getting a lot of great questions in the comments lately! I hope that means that many of you are getting your work out there, sliding it under agents’, editors’, and contest judges’ noses. Yes, the news from the publishing world, like the news from other sectors of the economy, is rather grim, but that does not mean landing an agent or selling a book is impossible.

As I am undoubtedly not the first person in the writers’ cosmos to say, the only manuscript that has absolutely NO chance of getting published is the one that’s never sent out. Keep plugging away.

On the often-unrelated subjects of both good questions from readers and submitting one’s work with style, insightful long-time reader Jen wrote in to ask:

I can’t help but think that the rules sink into my brain a little deeper with each reading. Still, sending off all those pages with nothing to protect them but the slim embrace of a USPS envelope seems to leave them too exposed. Where does one purchase a manuscript box?

This is an excellent question, Jen: many, many aspiring writers worry that a simple Manila envelope, or even the heavier-duty Priority Mail envelope favored by the US Postal Service, will not preserve their precious pages in pristine condition. Especially, as is all too common, if those pages are crammed into an envelope or container too small to hold them comfortably, or that smashes the SASE into them so hard that it leaves an indelible imprint in the paper.

Do I sense some readers scratching their heads? “But Anne,” some of you ask, “once a submission is is tucked into an envelope and mailed, it is completely out of the writer’s control. Aren’t the Millicents who inhabit agencies, as well as the Maurys who screen submissions at publishing houses and their Aunt Mehitabels who judge contest entries, fully aware that pages that arrive bent were probably mangled in transit, not by the writer who sent them?”

Well, yes and no, head-scratchers. Yes, pretty much everyone who has ever received a mauled letter is cognizant of the fact that envelopes do occasionally get caught in sorting machines. Also, mail gets tossed around a fair amount in transit — you think all of those packages in Santa’s sleigh have a smooth ride? Think again — so even a beautifully put-together submission packet may arrive a tad crumpled.

Do most professional readers cut the submitter slack for this? Sometimes; as I’ve mentioned before, if Millicent’s just burned her lip on that latté that she never seems to remember to let cool, it’s not going to take much for the next submission she opens to annoy her. And in the case of contest entries, I don’t know Aunt Mehitabel personally, but I have heard contest judges over the years complain vociferously to one another about the state in which entries have arrived on their reading desks.

All of which is to say: appearances count. You should make an effort to get your submission to its intended recipient in as neat a state as possible.

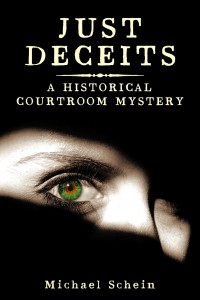

How does one go about insuring that? The most straightforward way, as Jen suggests, is to ship it in a box designed for the purpose. Something, perhaps, along the lines of this:

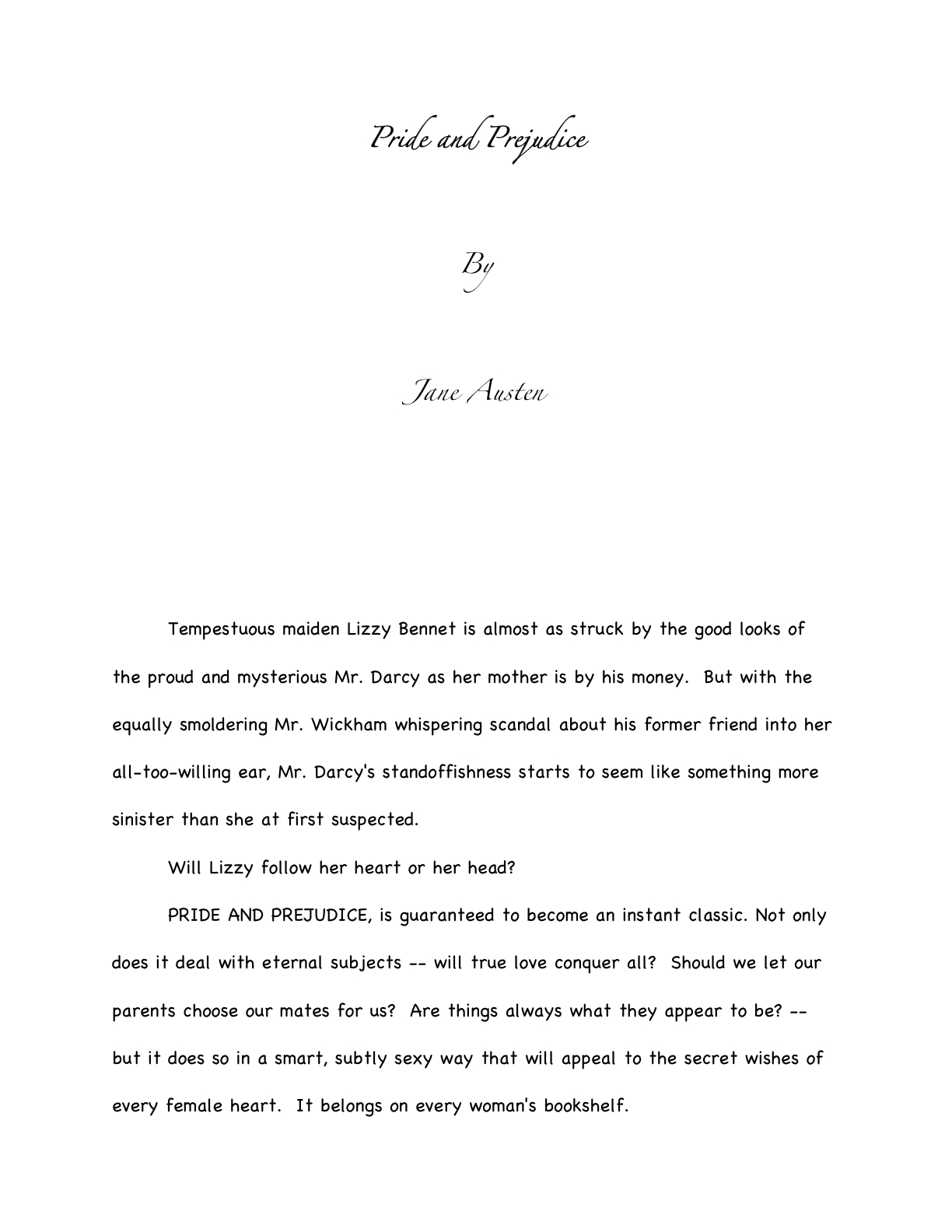

Just kidding; we’re not looking for a medieval Bible box here. What most writers like to use looks a little something like this:

This is the modern manuscript box: sturdy white or brown corrugated cardboard with a lid that is attached along one long side. Usually, a manuscript box will hold from 250 to 750 pages of text comfortably, without sliding from side to side.

While manuscript boxes are indeed very nice, they aren’t necessary for submission; the attached lid, while undoubtedly aesthetically pleasing, is not required, or even much appreciated at the agency end. Manuscripts are taken out of the boxes for perusal, anyway, so why fret about how the boxes that send them open?

In practice, any clean, previously-unused box large enough to hold all of the requested materials (more on that subject in my next post) without crumpling them will work to send a submission.

Some of you are resisting the notion of using just any old box, aren’t you, rather than one specially constructed for the purpose? I’m not entirely surprised. I hear all the time from writers stressing out about what kind of box to use — over and above clean, sturdy, and appropriately-sized, that is — and not without good reason. In the old days — say, 30+ years ago — the author was expected to provide a box, and a rather nice one, then wrap it in plain brown paper for shipping. These old boxes are beautiful, if you can still find one: dignified black cardboard, held together by shining brass brads.

For sending a manuscript, though, there’s no need to pack it in anything extravagant: no agent is going to look down upon your submission because it arrives in an inexpensive box.

In fact, if you can get the requested materials there in one piece box-free — say, if it is an excerpt short enough to fit into a Manila folder or Priority Mail cardboard envelope without much wrinking — go ahead. Do bear in mind, though, that you want to have your pages arrive looking fresh and unbent, so make sure that your manuscript fits comfortably in its holder in such a way that the pages are unlikely to wrinkle.

Remember my comment during the Manuscript Formating 101 series about its being penny-wise and pound-foolish to use cheap paper for submissions? This is part of the reason why.

Look for a box with the right footprint to ship a manuscript without too much internal shifting. In general, it’s better to get a box that is a little too big than one that’s a little too small. To keep the manuscript from sliding around and getting crumpled, insert wads of bubble wrap or handfuls of peanuts around it, not wadded-up paper. Yes, the latter is more environmentally-friendly, but we’re talking about presentation here.

Avoid the temptation to use newspaper, too; newsprint stains.

Most office supply stores carry perfectly serviceable white boxes — Office Depot, for instance, stocks a perfectly serviceable recycled cardboard variety — but if you live in the greater Seattle area, funky plastic junk store Archie McPhee’s, of all places, routinely carries fabulous red and blue boxes exactly the right size for a 450-page manuscript WITH adorable little black plastic handles for about a buck each. My agent gets a kick out of ‘em, reportedly, and while you’re picking one up, you can also snag a bobble-head Edgar Allan Poe doll that bears an uncomfortably close resemblance to Robert Goulet:

If that’s not one-stop holiday shopping, I should like to know what is.

Your local post office will probably stock manuscript-sized boxes as well, as does USPS online. Post offices often conceal some surprisingly inexpensive options behind those counters, so it is worth inquiring if you don’t see what you need on display.

Do be warned, though, that the USPS’ 8 1/2″ x 11″ boxes only LOOK as though they will fit a manuscript comfortably without bunching the pages. the actual footprint of the bottom of the box is the size of a piece of paper, so there is no wiggle room to, say, insert a stack of paper without wrinkling it.

Trust me, that’s NOT something you want to find out after you’ve already printed out your submission.

Yes, yes, I know: the USPS is purportedly the best postal service in the world, a boon to humanity, and one of the least expensive to boot. Their gallant carriers have been known to push forward through the proverbial sleet, hail, dark of night, and mean dogs. But when faced with an only apparently manuscript-ready box on a last-minute deadline, the thought must occur to even the most flag-proud: do the postal services of other countries confound their citizens in this way?

What do they expect anyone to put in an 8 1/2″ x 11″ box OTHER than a manuscript? A Christmas wreath? A pony? A small automobile?

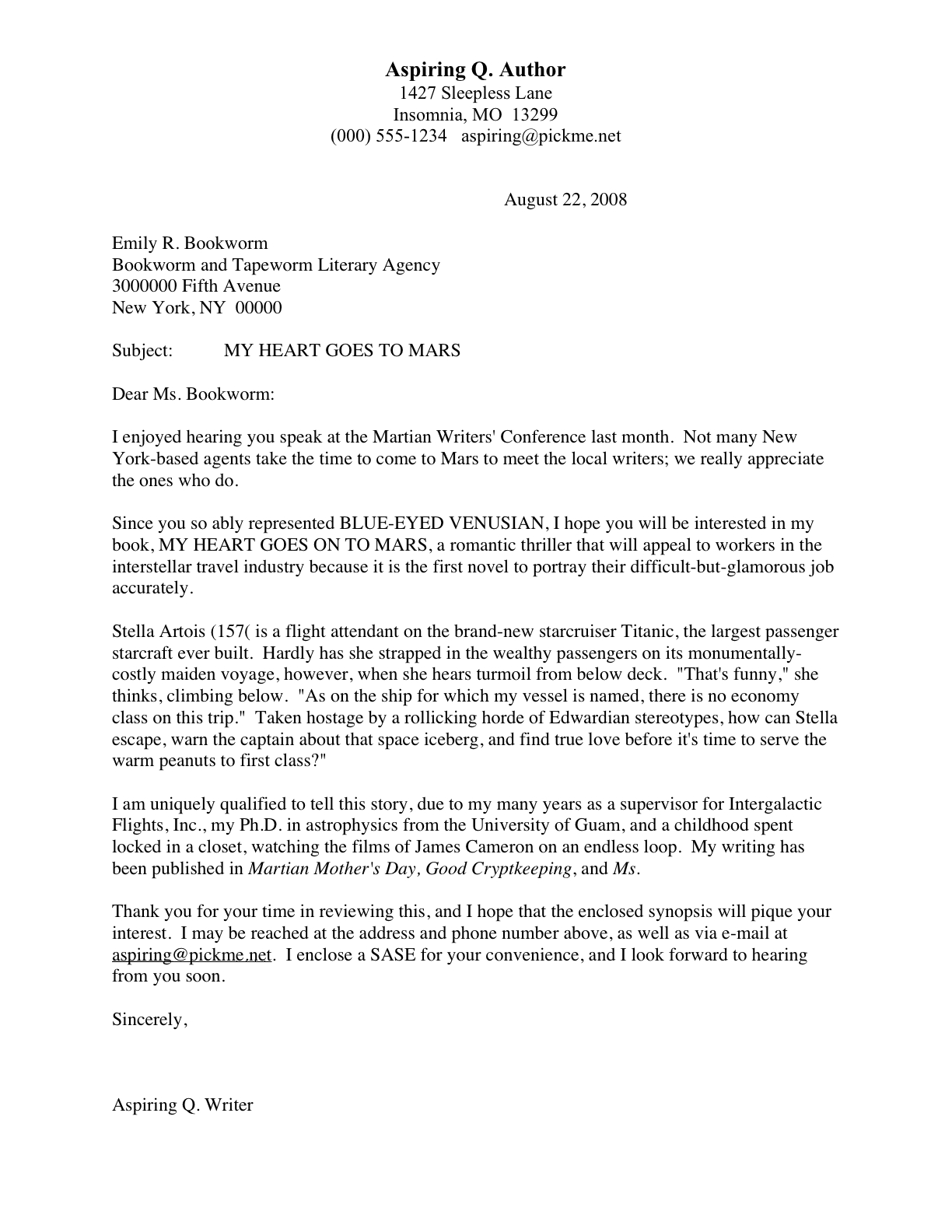

Far and away the most economical box source for US-based writers are those free all-you-can-stuff-in-it Priority Mail boxes that the post office provides:

Quite the sexy photo, isn’t it, considering that it’s of an object made of cardboard? Ravishing. If you don’t happen to mind all of the postal service propaganda printed all over it, these 12″ x 12″ x 5 1/2″ boxes work beautifully, with a little padding.

Say away from those wadded-up newspapers, I tell you.

While I’m on the subject of large boxes, if you’ve been asked to send more than one copy of a manuscript — not all that uncommon after you’ve been picked up by an agent — don’t even try to find a box that opens like a book: just use a standard shipping box. Insert a piece of colored paper between each copy, to render the copies easy to separate. Just make sure it’s not construction paper, or the color will rub off on your lovely manuscripts.

Whatever difficulties you may have finding an appropriately-sized box, DO NOT, under any circumstances, reuse a box clearly marked for some other purpose, such as holding dishwashing soap. As desirable as it might be for your pocketbook, your schedule, and the planet, never send your manuscript in a box that has already been used for another purpose.

You know what I mean, don’t you? We’ve all received (or sent) that box that began life as an mail-order shipping container, but is now covered with thick black marker, crossing out the original emporium’s name. My mother takes this process even farther, turning the lines intended to obfuscating that Amazon logo into little drawings of small creatures cavorting on a cardboard-and-ink landscape.

As dandy as this recycling is for birthday presents and the like, it’s considered a bit tacky in shipping a submission. Which is unfortunate, as the ones from Amazon tend to be a perfect footprint for manuscripts. Don’t yield to the temptation, though.

“But wait!” I hear the box-savvy cry, “those Amazon boxes are about 4 inches high, and my manuscript is about 3 inches high. It just cries out, ‘Stuff your manuscript into me and send me to an agent!’”

A word of advice: don’t take advice from cardboard boxes; they are not noted for their brilliance. Spring for something new.

And you do know that every time you send requested materials, you should write REQUESTED MATERIALS in great big letters in the lower left-hand corner of the submission envelope, don’t you? (If you have been asked to submit electronically, include the words REQUESTED MATERIALS in the subject line of the e-mail.) This will help your submission to land on the right desk, instead of in the slush pile or recycling bin.

Next time, I shall talk a little more about what goes INSIDE that manuscript box and in what order. In the meantime, keep up the good work!