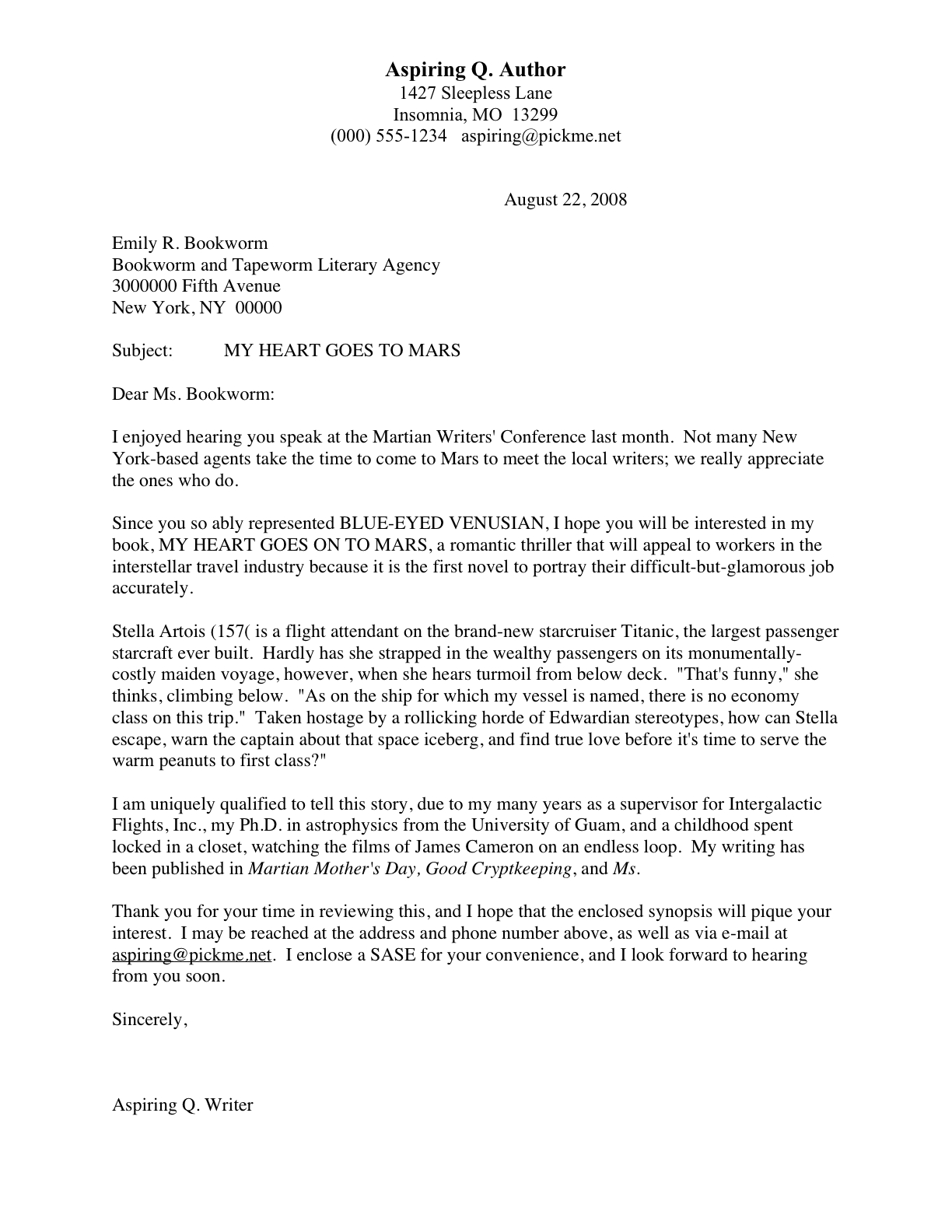

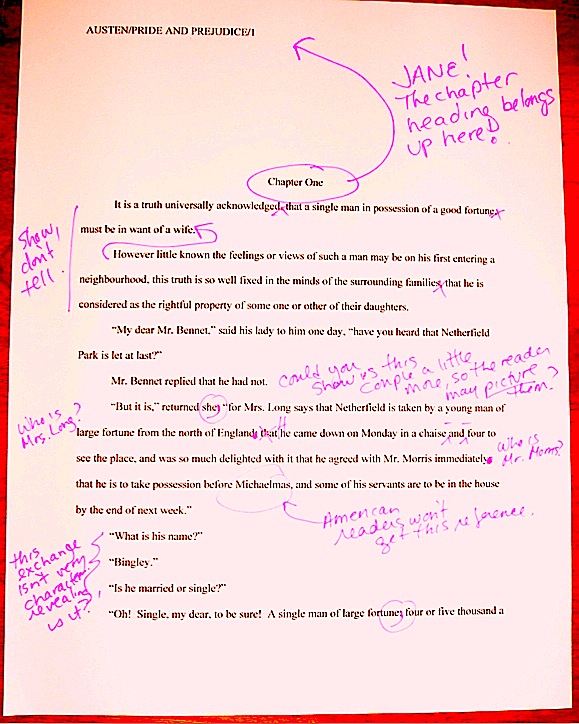

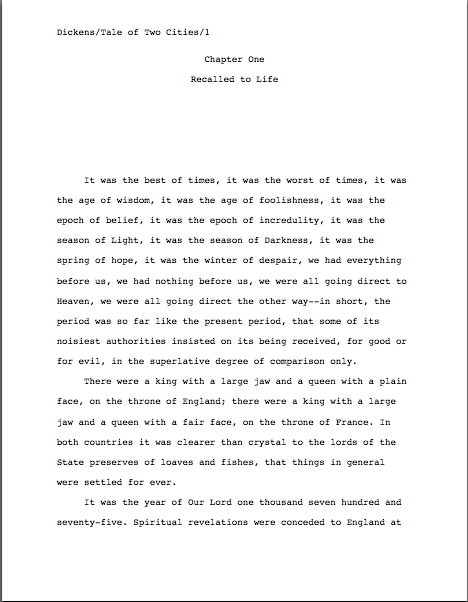

I’ve been talking for a few days about the goals of the query letter and how to achieve them without sounding as though you’re trying to sell the agent vacation home land in Florida. In that spirit, I thought some of you might find it useful to see what a really good query letter looks like. Not so you can copy it verbatim – rote reproductions abound in rejection piles – but so you may see what the theory looks like in practice.

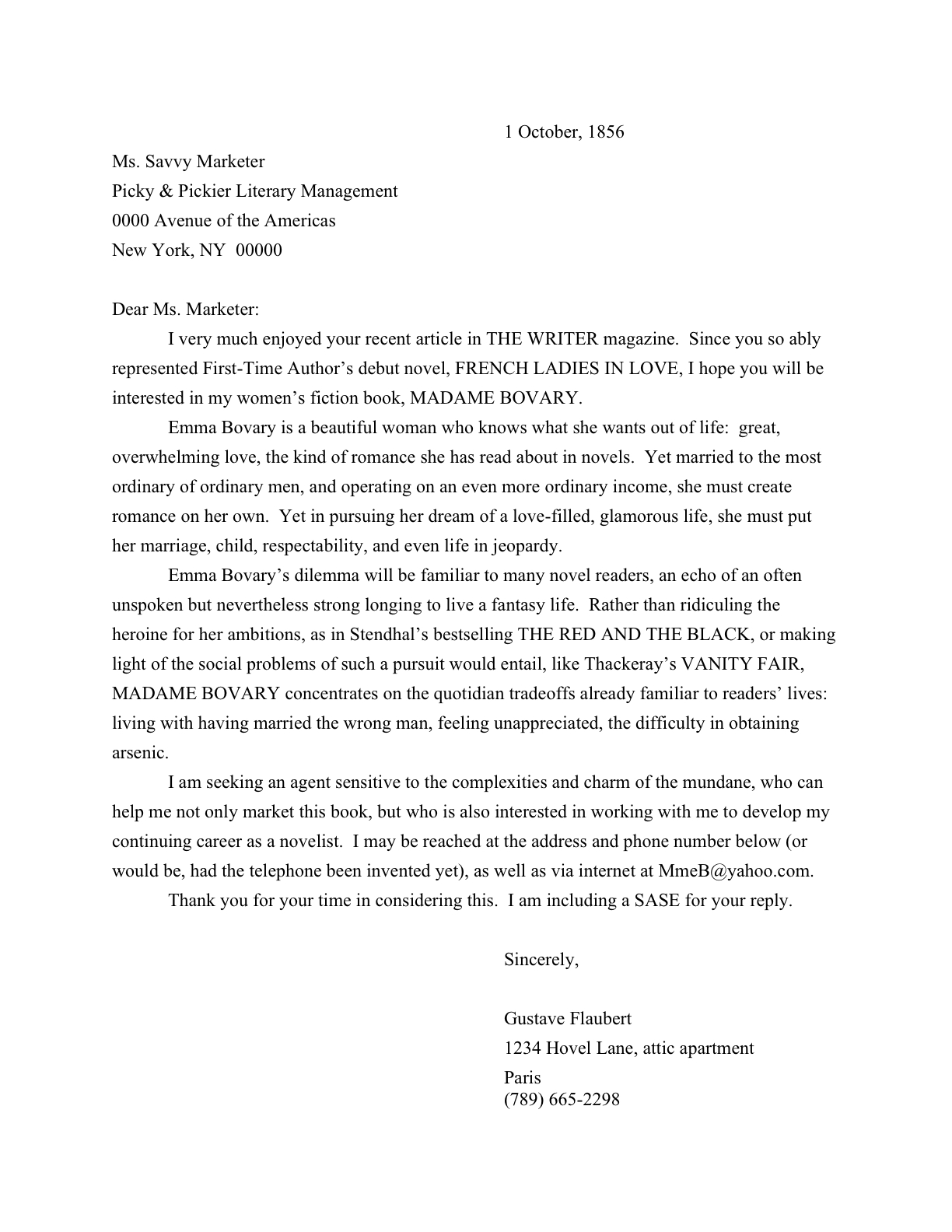

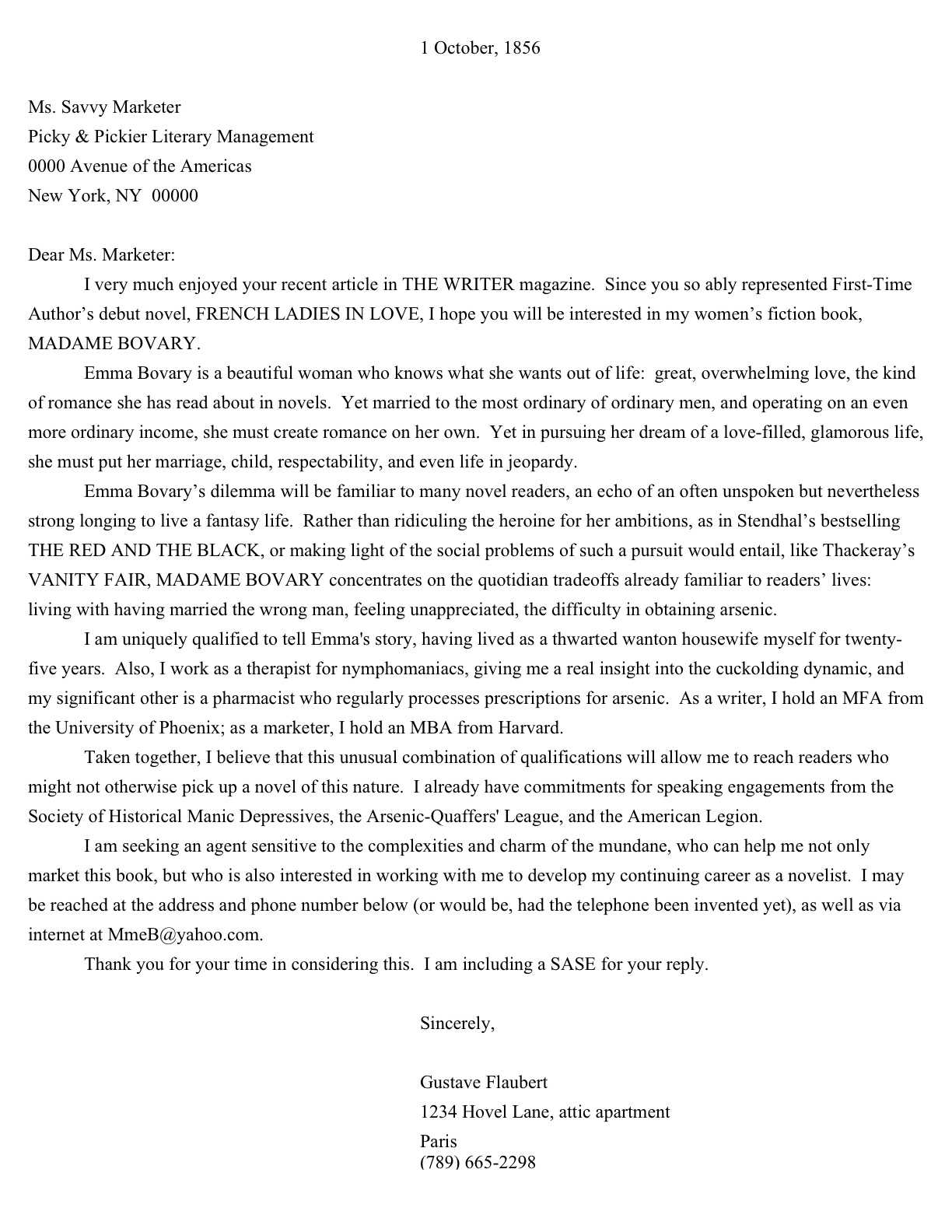

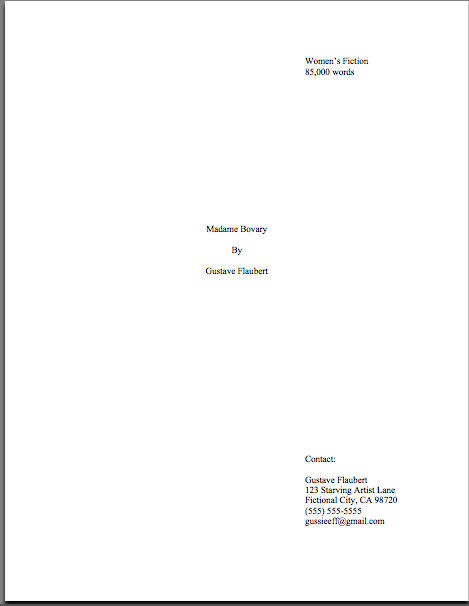

To make the example more useful, I’ve picked a book in the public domain whose story you might know: MADAME BOVARY. (And if you’re having trouble reading it at its current size, try clicking on the image a couple of times.)

That’s an awfully good query letter, isn’t it? After the last few days’ posts, I hope it’s clear to you why: it that presents the book well, in businesslike terms, without coming across as too pushy or arrogant. Even more pleasing to Millicent’s eye, Mssr. Flaubert makes the book sound genuinely interesting AND describes it in terms that imply a certain familiarity with how the publishing industry works. Well done, Gustave!

(The date on the letter is when the first installment of MADAME BOVARY was published, incidentally; I couldn’t resist.)

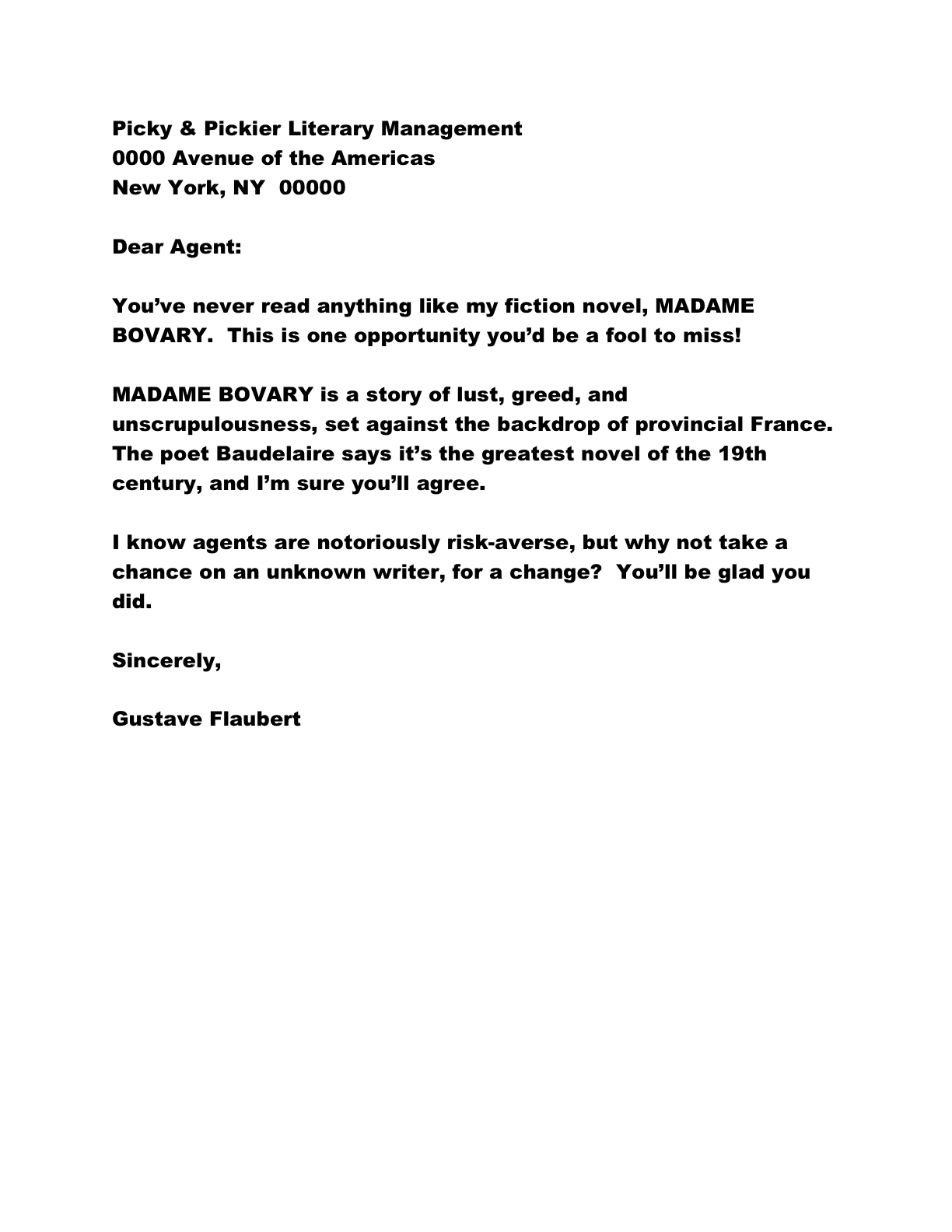

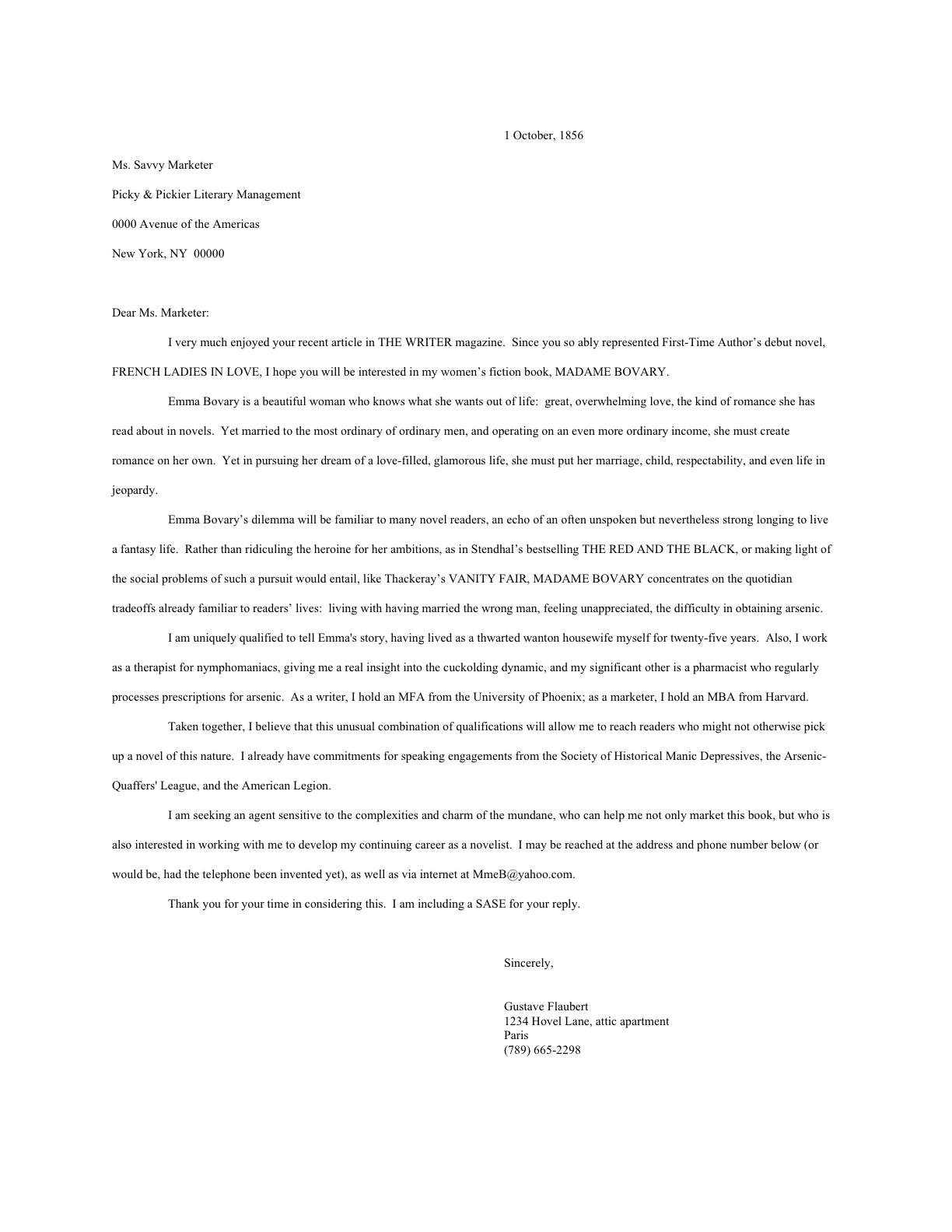

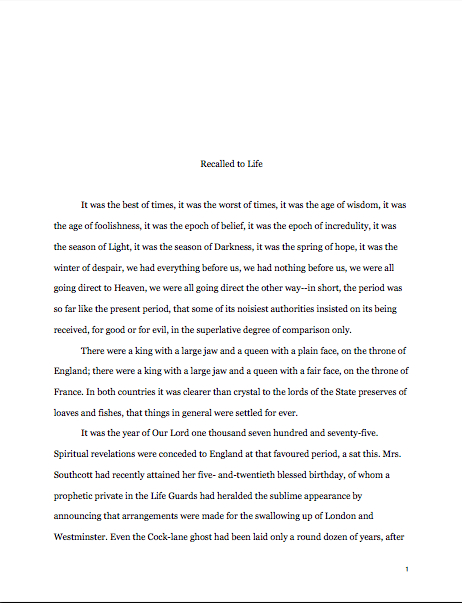

For the sake of comparison, let’s assume that Mssr. Flaubert had not done his homework; what might his query letter have looked like then?

Now, I respect my readers’ intelligence far too much to go through point by point, explaining what’s wrong with this second letter. Obviously, the contractions are far too casual for a professional missive.

No, but seriously, I would hope that you spotted the unsupported boasting, the bullying, disrespectful tone, and the fact that it doesn’t really describe the book. Also, to Millicent’s eye, the fact that it was addressed to DEAR AGENT and undated would indicate that ol’ Gustave is simply plastering the entire agent community with queries, regardless of individual agents’ representation preferences. That alone would almost certainly lead her to reject MADAME BOVARY out of hand, without reading the body of the letter at all.

Setting aside all of these problems, there are two other major problems with this letter that we have not yet discussed. First, how exactly is the agent to contact Gustave to request him to send the manuscript?

She can’t, of course, because Mssr. Flaubert has made the mistake of leaving out that information, as an astonishingly high percentage of queriers do.

Why? I suspect it’s because they assume that if they include a SASE (that’s Self-Addressed Stamped Envelope, for those of you new to the trade, and it should be included with every query and submission), the agent already has their contact information. A similar logic tends to prevail with e-mailed queries: all the agent needs to do is hit REPLY, right?

Well, no, not necessarily; e-mailed queries get forwarded from agent to assistant and back again all the time, and SASEs have been known to go astray. I speak from personal experience here: I once received a kind rejection for someone else’s book stuffed into my SASE. I returned the manuscript with a polite note informing the agency of the mistake, along with the suggestion that perhaps they had lost MY submission. The nice agency assistant who answered that letter — very considerately, as it happens — grew up to be my current agent.

True story.

The moral: don’t depend on the SASE or return button alone. Include your contact information either in the body of the letter or in its header.

Gustave’s second problem is a bit more subtle, not so much a major gaffe as a small signal to Millicent that the manuscript to which the letter refers MIGHT not be professionally polished. Any guesses?

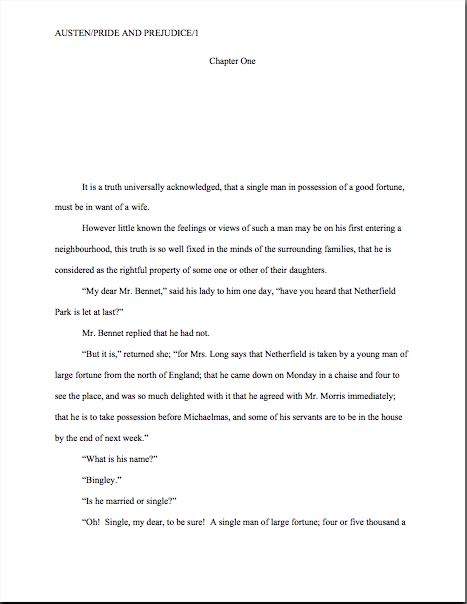

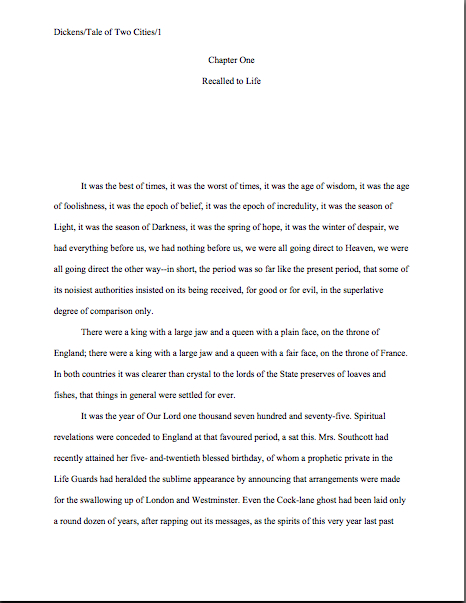

If you said that it was in business format, congratulations: you’ve been paying attention.

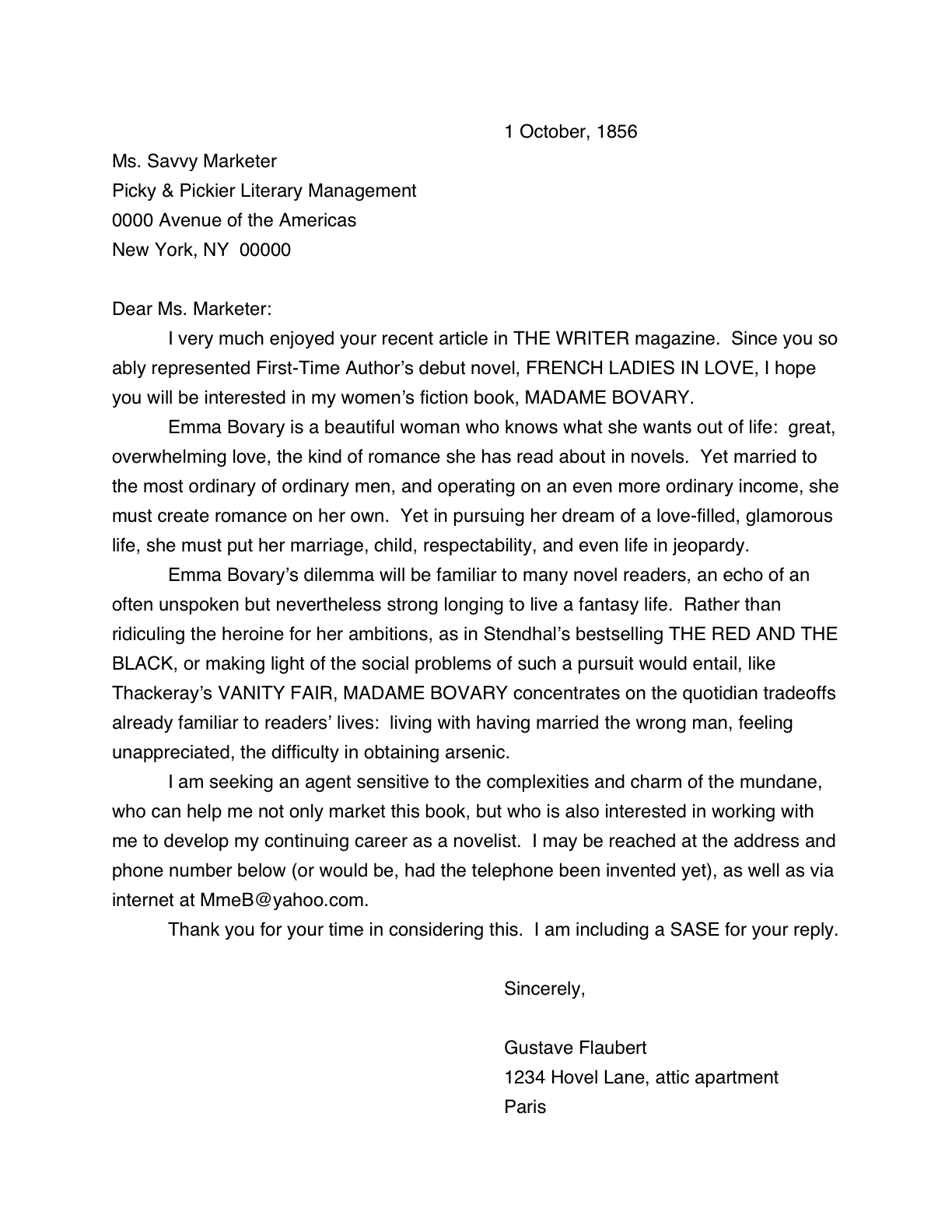

Any other ideas? Okay, let me infect the good query with the same virus, to help make the problem a bit more visible to the naked eye:

See it now? The letter is written in Helvetica, not Times, Times New Roman, or Courier, the preferred typefaces for manuscripts.

Was that huge huff of indignation that just billowed toward space an indication that favoring one font over another in queries is, well, a tad unfair? To set your minds at ease, I’ve never seen font choice alone be a rejection trigger (although font size often is; stick to 12 point). Nor do most agencies openly express font preferences for queries (although a few do; check their websites and/or agency book listings). However, I can tell you from very, very long experience working with aspiring writers that queries in the standard typefaces do seem to be treated with a touch more respect.

I know; odd. But worth noting, don’t you think?

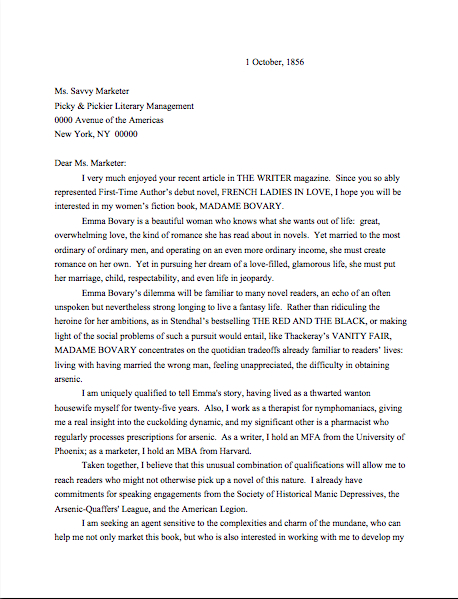

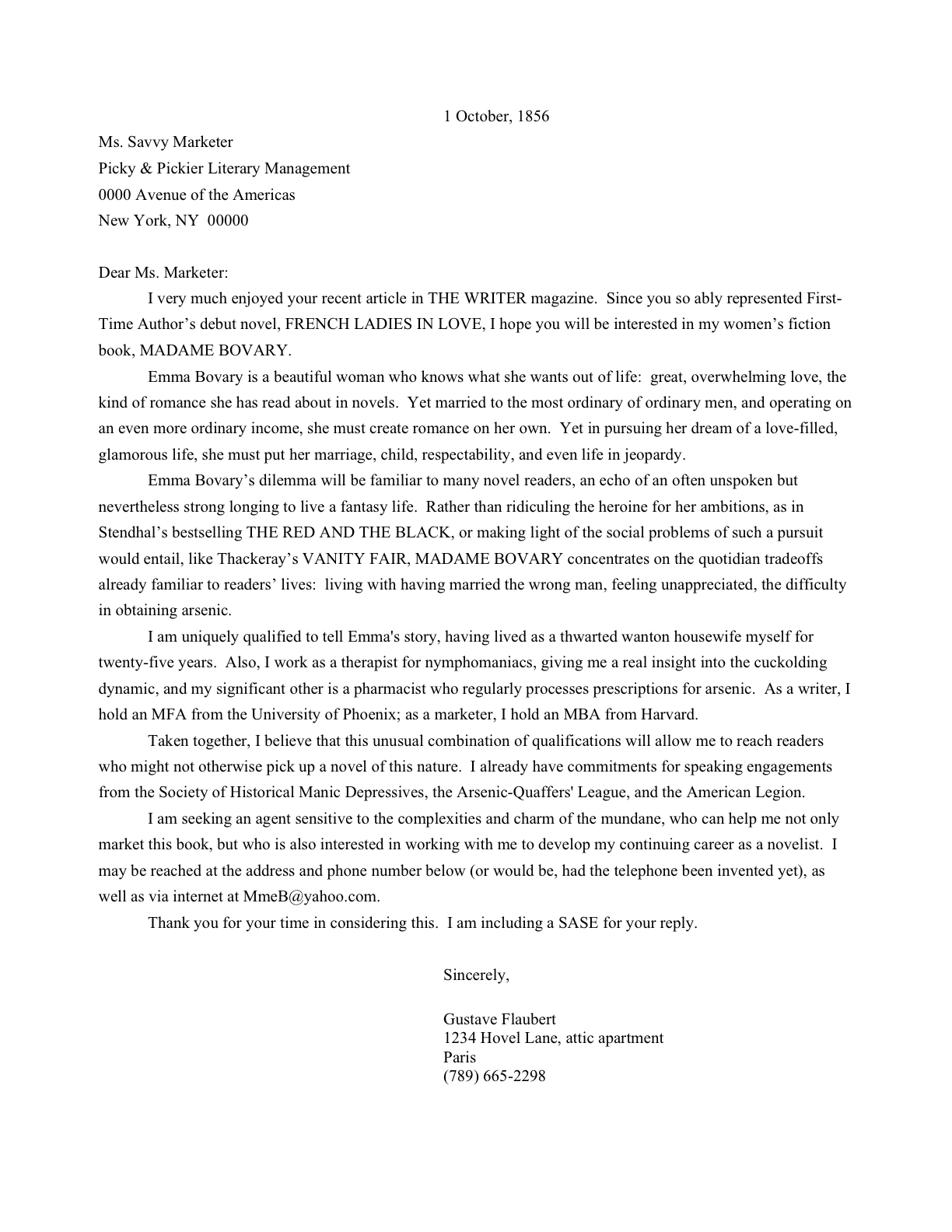

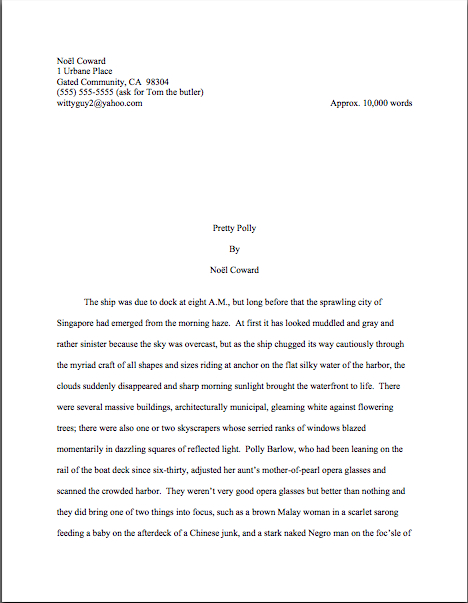

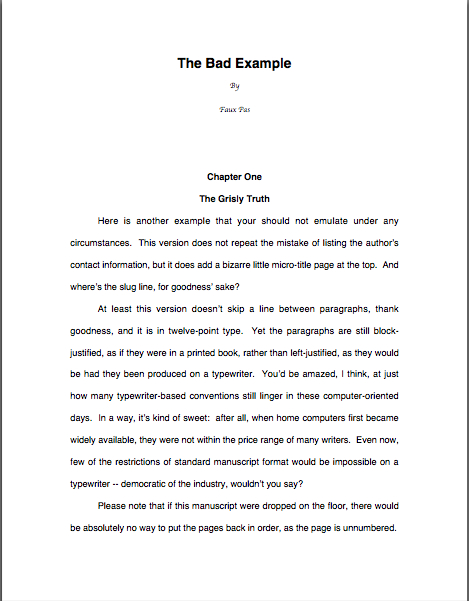

Let’s take a look at another common yet purely structural way that good query letters send off an unprofessional vibe:

Not all that subtle, this: a query letter needs to be a SINGLE page. This restriction is taken so seriously that very, very few Millicents would be willing to turn to that second page at all, few enough that it’s just not worth adding.

Why are agencies so rigid about length when dealing with people who are, after all, writers? Long-time readers, chant it with me now: TIME. Can you imagine how lengthy the average query letter would be if agencies didn’t limit how long writers could ramble on about their books?

Stop smiling. It would be awful, at least for Millicent.

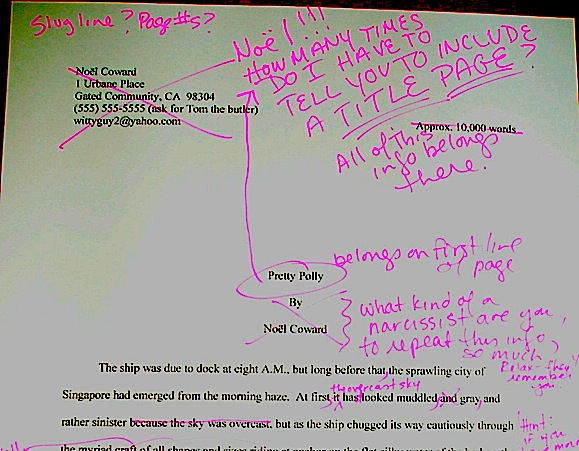

Fortunately, the one-page limit seems to be the most widely-known of querying rules. So much so, in fact, that aspiring writers frequently tempt Millicent’s wrath through conjuring tricks that force all of the information the writer wishes to provide onto a single page. Popular choices include shrinking the margins:

or shrinking the font size:

or, most effective at all, using the scale function to shrink the entire document:

Let me burst this bubble before any of you even try to blow it up to its full extent: this sort of document-altering magic will not help an over-long query sneak past Millicent’s scrutiny, for the exceedingly simple reason that she will not be fooled by it. Not even for a nanosecond. The only message such a query letter sends is this writer cannot follow directions.

Nor will an experienced contest judge, incidentally, should you be thinking of using any of these tricks to crush a too-lengthy chapter down to the maximum acceptable page length.

Why am I so certain that Millie will catch strategic shrinkage? For precisely the same reason that deviations from standard format in manuscripts are so obvious to professional readers: the fact that they read correctly-formatted pages ALL THE TIME.

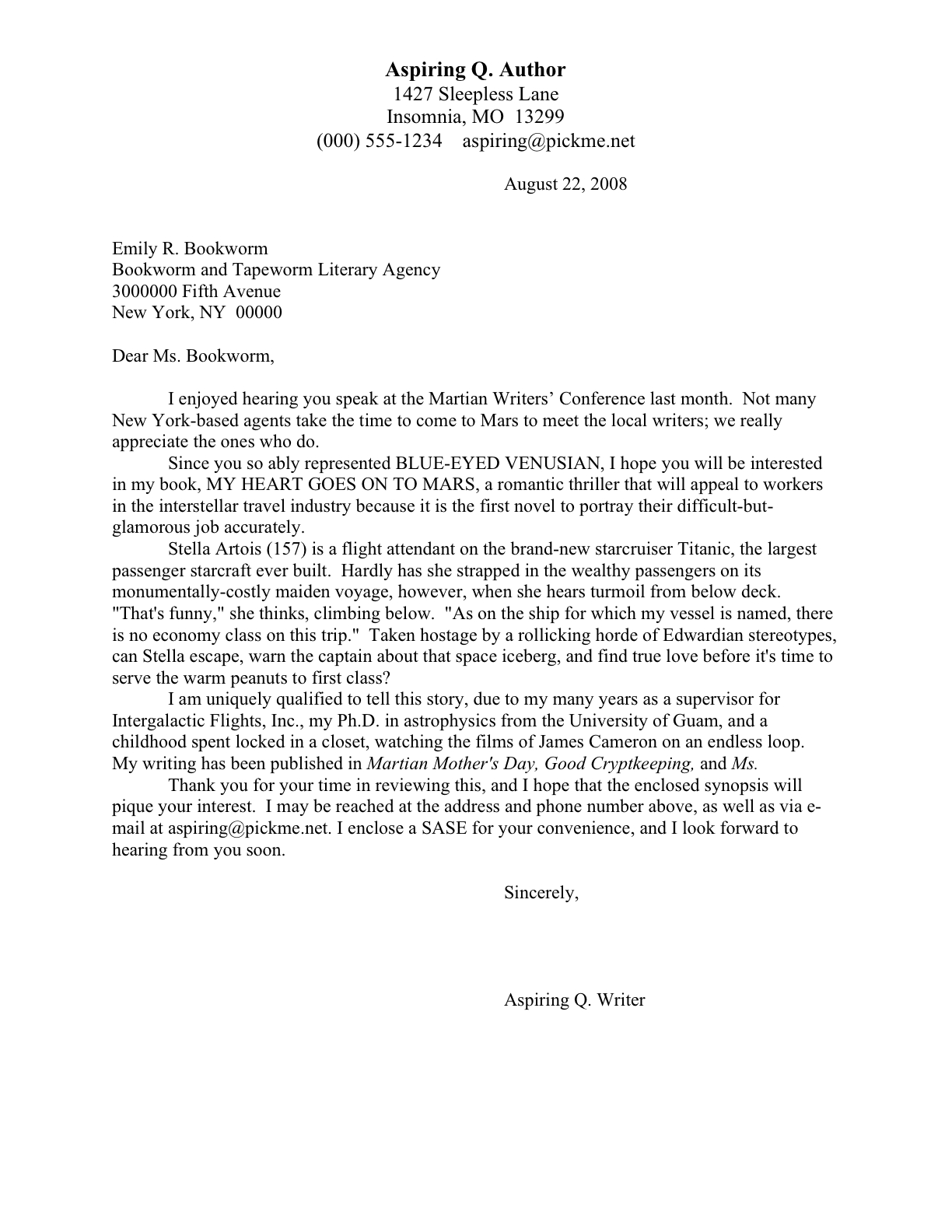

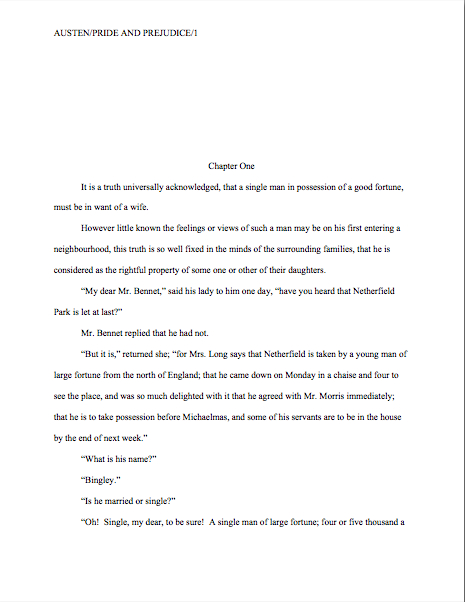

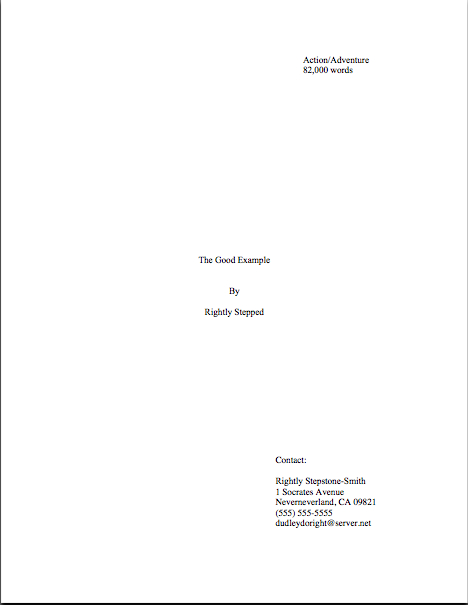

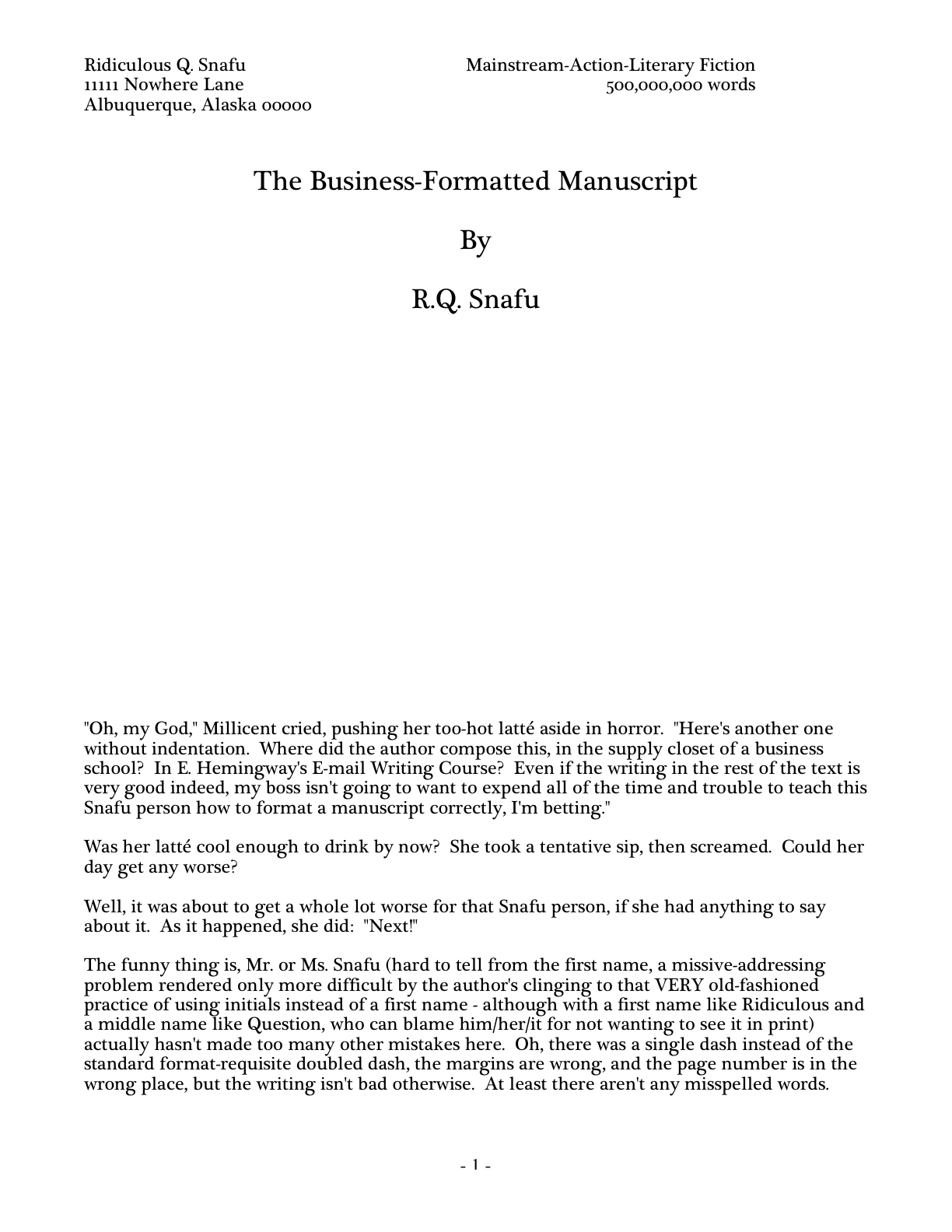

Don’t believe the tricks above wouldn’t be instantaneously spottable? Okay, glance at them, then take another gander at our first example of the day:

Viewed side-by-side, the differences are pretty clear, aren’t they? And in the extremely unlikely event that Millicent isn’t really sure that the query in front of her contains some trickery, all she has to do is move her fingertips a few inches to the right or the left of it, open the next query letter, and perform an enlightening little compare-and-contrast exercise.

Just don’t do it. But avoiding formatting skullduggery is not the only thing I would like you to learn from today’s examples.

What I would also like you to take away from this post is the fact that, with one egregious exception, these were all more or less the same query letter in terms of content, all pitching the same book. Yet only one of these is at all likely to engender a request to read the actual MANUSCRIPT.

In other words, even a great book will be rejected at the query letter if it is queried or pitched poorly. Yes, many agents would snap up Mssr. Flaubert in a heartbeat after reading his wonderful prose – but with a query letter like the second, or with some of the sneaky formatting tricks exhibited here, the probability of any agent’s asking to read it is close to zero.

Let’s not forget an important corollary to this realization: even a book as genuinely gorgeous as MADAME BOVARY would not see the inside of a Borders today unless Flaubert kept sending out query letters, rather than curling up in a ball after the first rejection.

Deep down, pretty much every writer believes that if she were REALLY talented, her work would get picked up without her having to market it. C’mon, admit it, you’ve had the fantasy: there’s a knock on your door, and when you open it, there’s the perfect agent standing there, contract in hand. “I heard that your work is wonderful,” the agent says. “May I come in and talk about it?’

Or perhaps in your preferred version, you go to a conference and pitch your work for the first time. The agent of your dreams, naturally, falls over backwards in his chair; after sal volitale has been administered to revive him from his faint, he cries, “That’s it! The book I’ve been looking for my whole professional life!”

Or, still more common, you send your first query letter to an agent, and you receive a phone call two days later, asking to see the entire manuscript. Three days after you overnight it to New York, the agent calls to say that she stayed up all night reading it, and is dying to represent you. Could you fly to New York immediately, so she could introduce you to the people who are going to pay a million dollars for your rights?

Fantasy is all very well in its place, but while you are trying to find an agent, please do not be swayed by it. Don’t send out only one query at a time; it’s truly a waste of your efforts. Try to keep 7 or 8 out at any given time.

This advice often comes as a shock to writers. “What do you mean, 7 or 8 at any given time? I’ve been rejected ten times, and I thought that meant I should lock myself away and revise the book completely before I sent it out again!”

In a word, no. Oh, feel free to lock yourself up and revise to your heart’s content, but if you have a completed manuscript in your desk drawer, you should try to keep a constant flow of query letters heading out your door. As they say in the biz, the only manuscript that can never be sold is the one that is never submitted. (For a great, inspiring cheerleading essay on how writers talk themselves out of believing this, check out Carolyn See’s Making a Literary Life.)

There are two reasons keeping a constant flow is a good idea, professionally speaking. First, it’s never a good idea to allow a query letter to molder on your desktop: after awhile, that form letter can start to seem very personally damning, and a single rejection from a single agent can start to feel like an entire industry’s indictment of your work.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: one of the most self-destructive of conference-circuit rumors is the notion that if a book is good, it will automatically be picked up by the first agent that sees it. Or the fifth, for that matter.

This is simply untrue. It is not uncommon for wonderful books to go through dozens of queries, and even many rounds of query-revision-query-revision before being picked up. As long-time readers of this blog are already aware, there are hundreds of reasons that agents and their screeners reject manuscripts, the most common being that they do not like to represent a particular kind of book.

So how precisely is such a rejection a reflection on the quality of the writing?

Keep on sending out those queries a hundred times, if necessary. Because until you can blandish the right agent into reading your book, you’re just not going to know for sure whether it is marketable or not.

More querying tips follow anon. Keep up the good work!