How’s everybody doing out there? Are all of you nonfiction writers excited that I’ve been talking about writing specific to your book categories, or is everyone still too burned out from New Year’s festivities that you’re sitting there, glassy-eyed, silently willing the first Monday of 2011 to be over, already? Or — and I sincerely hope this is the case — are you paying attention to this post with one part of your brain, while another delightedly plots how to polish up your entries to the Author! Author! Rings True Writing Competition? There are both fiction and nonfiction categories this time around, folks, so I hope all of you memoirists who just dropped by for the formatting tips will at least consider entering.

Personally, I can’t wait to see what you’ll send in. As those of you who have been hanging out here at Author! Author! for a while may have sensed, I honestly do like to see what my readers are writing.

And, of course, to know how I can help you present your manuscripts and proposals more professionally. If you have a question about standard format, or something for which you would like to see more practical examples, by all means, let me know. That’s why the comment function is there, folks!

Seriously, it’s to everybody’s benefit if you ask; trust me, if you have been wondering, so have hundreds of other writers. The overwhelming majority of aspiring writers have never seen a professionally-formatted manuscript or book proposal, after all. I would much, much rather you asked me than took a wild guess in your submissions.

Readers’ questions also allow me to fine-tune the archive list at right — I want to make it as intuitive as possible for a panicked aspiring writer to use. (Speaking of which, since no one has commented yet on last November’s rather radical rearrangement of the archive list, am I to conclude that (a) most of you are finding it easier to use than its previous incarnation, (b) most of you are finding it harder to use, but are too polite to say so, (c) despite the monumental effort of rearranging it under subheadings, the result is precisely as user-friendly as the simple alphabetical list it replaced, or (d) nobody has noticed? It would be quite helpful for me to know.)

I’m particularly interested in finding out what pieces of information are comparatively difficult to find in my frankly pretty hefty archives. Why, only last February, eagle-eyed reader Kim was kind enough to point out a fairly extensive omission in my twice-yearly examinations of standard format for manuscripts: although I had been providing illustrations of same for several years now, I’d never shown the innards of a properly-formatted book proposal. In fact, as Kim explained,

Anne — Thank you for this glorious blog. It is a wealth of information. I am putting together a submissions package (requested materials, yea!), which includes a book proposal. After searching through your site, I still can’t find a specific format for the thing. For example, should the chapter summaries be outlined? double-spaced? Should I start a new page for each subheading? Also, my book has several very short chapters (80 in total). Should I group some of them together in the summaries, lest it run too long? Or is it better to give a one sentence description of each? Thanks again.

My first response to this thoughtful set of observations, I must admit, was to say, “No way!” After all, I had written a quite extensive series entitled HOW TO WRITE A BOOK PROPOSAL (beginning here) as recently as…wait, did that date stamp say August of 2005?

As in within a month of when I started this blog? More to the point, since before I sold my second nonfiction book to a publisher? (No, you haven’t missed any big announcements, long-time readers: that one isn’t out yet, either.)

Clearly, I had a bit of catching up to do. Equally clearly, I am deeply indebted to my intrepid readers for telling me when they cannot find answers to their burning questions in the hugely extensive Author! Author! archives.

The burning question du jour: how is a book proposal formatted differently than a book manuscript? Or is it?

In most ways, it isn’t; in some ways, however, it is. Rather than assume, as I apparently did for four and a half years, that merely saying that book proposals should be in standard manuscript format (with certain minimal exceptions), let’s see what that might look like in action.

In fact, since I’ve been going over the constituent parts in order, let’s go ahead recap from the beginning, talking a little about what purpose each portion of it serves. Here, ladies and gentlemen of the Author! Author! community, are the building blocks of a professional book proposal, illustrated for your pleasure. As you will see, much of it is identical in presentation to a manuscript.

1. The title page

Like any other submission to an agent or editor, a book proposal should have a title page. Why? To make it easier to contact you — or your agent — and buy the book, of course.

As we discussed in our last ‘Palooza post, once a writer has landed an agent, the agency’s contact information belongs on the title page, so the editor of one’s dreams may contact one’s agent easily to acquire the book. Prior to either the happy day of an offer on one’s book or the equally blissful day one signs with an agent, the writer’s contact information belongs on the title page.

2. The overview

First-time proposers often shirk on this part, assuming — wrongly — that all that’s required to propose a nonfiction book is to provide the kind of 1-, 3-, or 5-page synopsis one might tuck into a query packet. In practice, however, a successful overview serves a wide variety of purposes:

(a) It tells the agent or editor what the proposed book will be about, and why you are the single best person on earth to write about it. Pretty much everyone gets that first part, but presenting one’s platform credibly is often overlooked in an overview. (I hate to be the one to break it to you, but if an agent or editor makes it to the bottom of page 3 of your proposal without understanding why you are a credible narrator for this topic, your proposal is going to fall flat, no matter how inherently interesting your topic may be.

(b) It presents the central question or problem of the book, explaining why the topic is important and to whom , amplifying on the argument in (a), couching it in larger terms and trends. Or, to put it another way: why will the world be a better place if this book is published?

No, that’s not an egomaniac’s way to look at it. Why do your readers need to read this book? How will their lives or understanding of the world around them be strengthened or reshaped by it?

(c) It demonstrates why this book is needed now, as opposed to any other time in literary history. That one is self-explanatory, I hope.

(d) It answers the burning question: who is the target audience for this book, anyway? To reframe the question as Millicent’s boss will: how big is the intended market for this book, and how do we know that they’re ready to buy a book on this subject?

(e) It explains why this book will appeal to the target audience as no book currently on the market will. (In other words, how are potential readers’ needs not being served by what’s been published within the last five years — the usual definition of the current market — and why will your book serve those needs in a better, or at any rate different, manner?

(f) It shows how your platform will enable you to reach this target audience better than anyone else who might conceivably write this book. Essentially, this involves tying together all of the foregoing, adding your platform, and stirring.

(g) It makes abundantly clear the fact that you can write. Because, lest we forget, a book proposal is a job application at base: the writer’s primary goal is to get an agent or editor to believe that she is the right person to hire to write the book she’s proposing.

Yes, there should be separate sections of the book proposal that address all of these points in detail. The overview is just that: a quick summary of all of the important selling points for your book, presented in a manner intended to entice an agent or editor to read on to the specifics.

In the interest of establishing points (a), (b), and (g) right off the bat, I like to open a book proposal with an illustrative anecdote or direct personal appeal that thrusts the reader right smack into the middle of the central problem of the piece, reducing it to an individual human level. Basically, the point here is to answer the question why would a reader care about this subject? within the first few lines of the proposal, while showing off the writer’s best prose.

For a general nonfiction book — particularly one on a subject that Millicent might at first glance assume, perish the thought, to be a bit on the dry side — this is a great opportunity for the writer to give a very concrete impression of why a reader might care very deeply about the issue at hand. Often, the pros open such an anecdote with a rhetorical question.

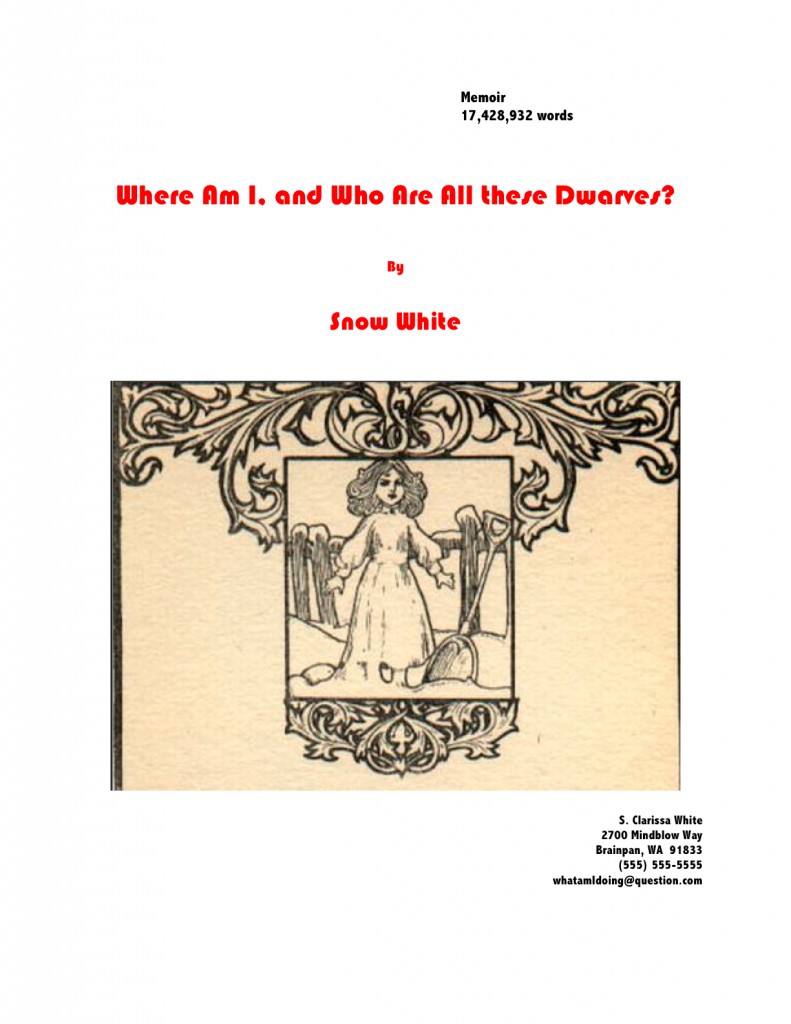

The opening anecdote gambit works especially well for a memoir proposal, establishing both the voice and that the memoir’s central figure is an interesting person in an interesting situation. While it’s best to keep the anecdote brief — say, anywhere between a paragraph and a page and a half — it’s crucial to grab Millicent’s attention with vividly-drawn details and surprising turns of event. To revisit our example from last time:

As we saw in that last example, you can move from the anecdote or opening appeal without fanfare, simply by inserting a section break — in other words, by skipping a line. While many book proposals continue this practice throughout the overview, it’s visually more appealing to mark its more important sections with subheadings, like so:

Incorporating subheadings, while not strictly speaking necessary, renders it very, very easy for Millicent the agency screener to find the answers to the basic questions any book proposal must answer. If the text of the proposal can address those questions in a businesslike tone that’s also indicative of the intended voice of the proposed book, so much the better.

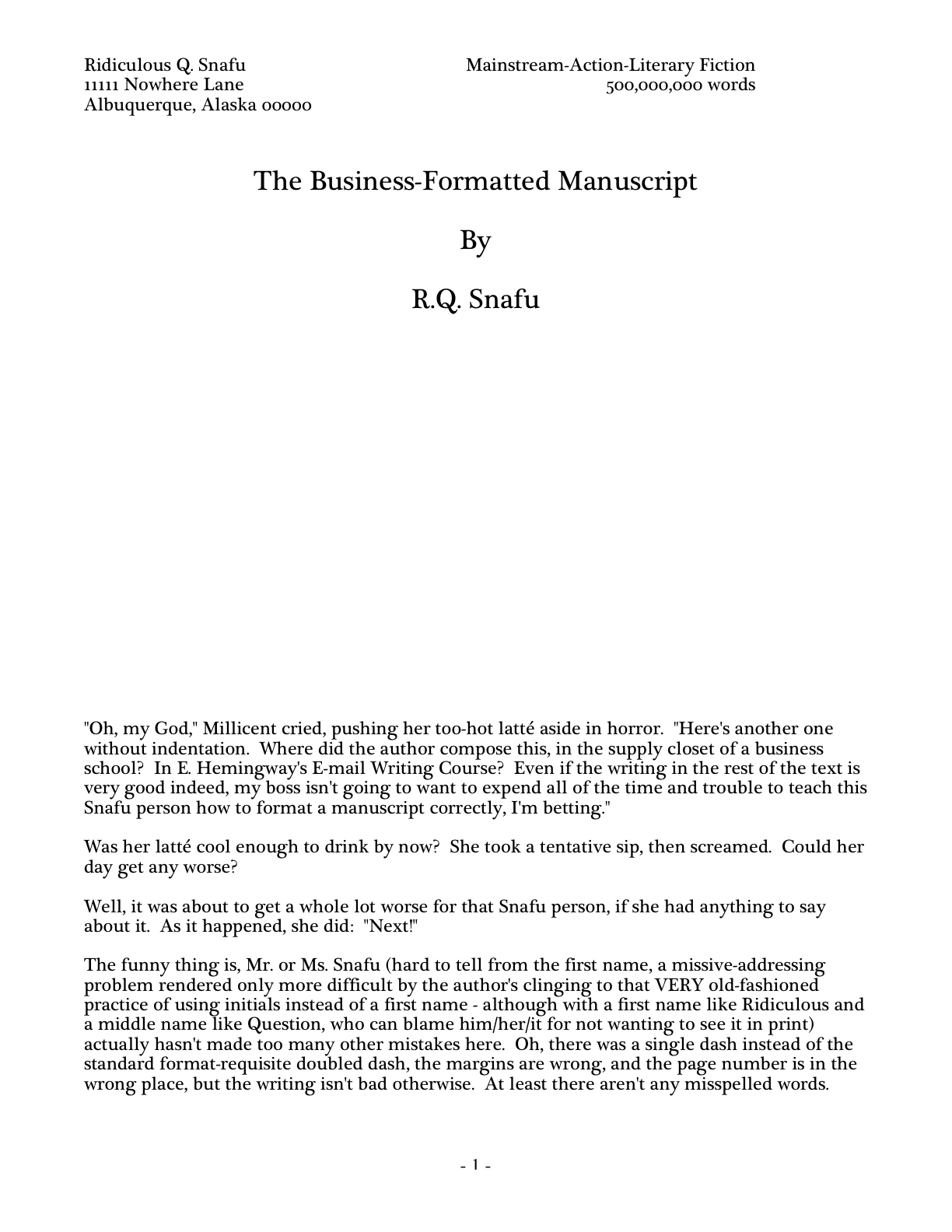

Please note, however, that I said businesslike, not in business format. Under no circumstances should a book proposal either be single-spaced or present non-indented paragraphs.

This one confuses a lot of first-time proposers, I’ve noticed. “But Anne!” they protest, and not entirely without justification. “A book proposal is a business document, isn’t it? Doesn’t that mean that it should be in business format?”

The short answer is my God — no! The not-so-short answer is: not if you want Millicent to read it. An aspiring writer who does not indent her paragraphs is presumed illiterate.

Long-time readers, chant it with me now: the publishing industry does not use business format, even in its business letters; always, always, ALWAYS indent your paragraphs.

3. The competitive market analysis

The competitive market analysis is probably the most widely misunderstood portion of the book proposal. What the pros expect to see here is a brief examination of similar books that have come out within the last five years, accompanied by an explanation of how the book being proposed will serve the shared target audience’s needs in a different and/or better manner. Not intended to be an exhaustive list, the competitive market analysis uses the publishing successes of similar books in order to make a case that there is a demonstrable already-existing audience for this book.

But that’s not how you’ve heard this section described, is it? Let me take a stab at what most of you have probably heard: it’s a list of 6-12 similar books.

Period. The sad, sad result usually looks like this:

Makes it pretty plain that the writer thinks all that’s required here is proof that there actually have been other books published on the subject in the past, doesn’t it? Unfortunately, to Millicent’s critical eye, such a list doesn’t merely seem like ignorance of the goal of the competitive market analysis — it comes across as proof positive of the authorial laziness of a writer who hasn’t bothered to learn much about either how books are proposed or the current market for the book he’s proposing.

To be fair, this is the section where first-time proposers are most likely to skimp on the effort. Never a good idea, but a particularly poor tactic here. After all of these years, the average Millicent is darned tired of proposers missing the point of this section: all too often, first-time proposers assume that it has no point, other than to create busywork.

As you may see above, the bare-bones competitive market analysis makes the writer seem as if he’s gone out of his way to demonstrate just how stupid he thinks this particular exercise is. That’s because he’s missed the point of the exercise.

The goal here is not merely to show that other books exist, but that the book being proposed shares salient traits with books that readers are already buying. And because the publishing industry’s conception of the current market is not identical to what is actually on bookstore shelves at the moment, the savvy proposer includes in his competitive market analysis only books that have been released by major houses within the last five years.

That last point made some of you choke on your tea, didn’t it? Don’t you wish someone had mentioned that little tidbit to you before the first time you proposed?

Even when proposers do take the time to research and present the appropriate titles, a handful of other mistakes tend to mark the rookie’s proposal for Millicent. Rather than show you each of them individually, here’s an example that includes several. Take out your magnifying glass and see how many you can catch.

How did you do?

Let’s take the more straightforward, cosmetic problems first, the ones that should immediately leap out at anyone familiar with standard format. There’s no slug line, for starters: if this page fell out of the proposal — as it might; remember, proposals are unbound — Millicent would have no idea to which of the 17 proposals currently on her desk it belonged. It does contain a page number, but an unprofessionally-presented one, lingering at the bottom of the page with, heaven help us, dashes on either side.

Then, too, one of the titles is underlined, rather than italicized, demonstrating formatting inconsistency, and not all of the numbers under 100 are written out in full. Not to mention the fact that it’s single-spaced!

All of this is just going to look tacky to Millie, right?

Okay, what else? Obviously, this version is still presented as a list, albeit one that includes some actual analysis of the works in question; it should be in narrative form. Also, it includes the ISBN numbers, which to many Millicent implies — outrageously! — a writerly expectation that she’s going to take the time to look up the sales records on all of these books.

I can tell you now: it’s not gonna happen. If a particular book was a runaway bestseller, the analysis should have mentioned that salient fact.

There’s one other, subtler problem with this example — did you catch it?

I wouldn’t be astonished if you hadn’t; many a pro falls into this particular trap. Let’s take a peek at this same set of information, presented as it should be, to see if the gaffe jumps out at you by contrast.

Any guesses? How about the fact that the last example’s criticism is much, much gentler than the one immediately before it?

Much too frequently, those new to proposing books will assume, wrongly, that their job in the competitive market analysis is rip apart every previous book on the subject. They try to make the case that every other book currently available has no redeeming features, as a means of making their own book concepts look better by contrast.

Strategically, this is almost always a mistake. Anybody out there have any ideas why?

If it occurred to you that perhaps, just perhaps, the editors, or even the agents, who handled the books mentioned might conceivably end up reading this book proposal, give yourself three gold stars. It’s likely, isn’t it? After all, agents and editors both tend to specialize; do you honestly want the guy who edited the book you trashed to know that you thought it was terrible?

Let me answer that one for you: no, you do not. Nor do you want to insult that author’s agent. Trust me on this one.

No need to go overboard and imply that a book you hated was the best thing you’ve ever read, of course — the point here is to show how your book will be different and better, so you will need some basis for comparison. You might want to avoid phrases like terrible, awful, or an unforgivable waste of good paper, okay?

I had hoped to get a little farther in the proposal, but as I’m already running long, I’m going to sign off for the day. But since you’re all doing so well, here’s one final pop quiz before I go: what lingering problem remains in this last version, something that might give even an interested Millicent pause in approving this proposal?

If you immediately leapt to your feet, shouting, “I know! I know! Most of these books came out more than five years ago, and of those, The Gluten-Free Gourmet is the only one that might be well enough known to justify including otherwise,” give yourself seven gold stars for the day.

Heck, take the rest of the day off; I am. Keep up the good work!

Please recognize that not everything that falls under the general rubric writing should be formatted identically. Book manuscripts should be formatted one way, short stories (to use the most commonly-encountered other set of rules) another.

Please recognize that not everything that falls under the general rubric writing should be formatted identically. Book manuscripts should be formatted one way, short stories (to use the most commonly-encountered other set of rules) another.

Please, I implore you, do not put off writing at least a viable first draft of your bio until the day after an agent or editor has actually asked you to provide one. Set aside some time to do it soon.

Please, I implore you, do not put off writing at least a viable first draft of your bio until the day after an agent or editor has actually asked you to provide one. Set aside some time to do it soon.