Hello again, campers –

Remember how I promised a few days ago to give you a treat for working so hard throughout the Manuscript Formatting 101 series? (Yes, I honestly do know it’s no fun for anyone concerned. Things that are good for one often aren’t.) Well, today is Treat Day — and I’m delighted to report that tomorrow will be as well.

Don’t you feel virtuous now? Doubly so?

I’m excessively pleased about this particular treat, because it’s not something I’ve been able to finagle for all of you here at Author! Author! before: a first-hand account from a FAAB (Friend of Author! Author! Blog) of what it’s like to be on a book tour by a recently-published author.

Yes, really. Pinch me, somebody.

To make this treat better yet, FAAB Michael Schein, author of the recently-released JUST DECEITS is not only going to share his on-the-road experiences with us, but also give us some tips on how to set up public readings, attract potential book buyers to them, and sell copies of one’s book once they’re there.

I told you it was going to be a good treat.

So please join me in welcoming Michael Schein; take good notes, because you are going to be deeply grateful for his insight someday. If you’d like to see him in action at one of his own book signings, here’s a link to his tour schedule.

Keep up the good work, and take it away, Michael!

November 17. 12:59 Eastern Time. 24,997 feet. Descending into Atlanta. Turbulence. Welcome to the book tour for Just Deceits: A Historical Courtroom Mystery (Bennett & Hastings 2008). I’m Michael Schein, author, publicist and traveling salesman, and I’ll be your host. Let’s talk about that particular aspect of book promotion known and romanticized in many Hollywood films and in the fertile imagination of the unpublished writer as the book tour.

Let me begin by saying that I am grateful to be at this point in my life, in which I have a trade paperback published by a small Seattle press, and I have the freedom and frequent flyer miles (“earned” by charging too much on my VISA) to be able to go out and peddle my book.

Between that paragraph and this one much has happened! I wrote that in Atlanta while awaiting my flight to Norfolk. We took off, but the plane seemed to falter on its ascent. It was quiet and creepy. We turned. We lost a little altitude. We turned some more. We heard engines, but they were too quiet. We heard nothing from the flight attendants, who remained buckled in and stone-faced. We were about three to five thousand feet up – the trees and houses were still clearly distinguishable. Finally, we were told we were returning to Atlanta due to a little problem but not to worry, the engines were working fine.

OK, great, what else keeps a plane up? Wings? Rudder? Flaps? God? who never hears from me except to curse and write atheistic poetry?

A minute can be a long time.

We were up for about twenty to thirty of them. But the fact that I’m writing this tips off the happy ending. Yes, a safe landing. Turns out the throttle lever got stuck – that’s not good, is it? No matter how well the engines are functioning, without fuel their proper function is to shut down! Anyway, our crack pilots got it unstuck.

To make a long story short, we changed planes, and got to sit on a new plane without ventilation for an hour while we waited for the crew, plus another hour while we waited for soft drinks.

There’s logic: delay a one hour seven minute flight (airtime) one hour to be sure you can serve the thirsty cranky denizens a Pepsi which the few who actually drink that treacly syrup would have been able to purchase at their destination just as quickly.

But I wasn’t complaining. Alive was good enough for me. All this to sell a book! And so far, all I’ve managed is give away the copy in my carry on to my seat mate, who didn’t offer to buy one.

But as I blew along 64 West from Norfolk (or NorF*ck; to pronounce it right, “you have to say the dirty word,” I was told) to Williamsburg in my rented Kia, and chanced upon Simon & Garfunkel’s Kathy from Bookends with its magnificent chorus of “All come to look for America!” just as I passed the exit for Historic Jamestown Settlement, I had to pinch myself to be sure I hadn’t died and gone to heaven.

Setting up the book tour. Here’s what I know about setting up a book tour. The first and most important thing to realize is that most bookstores don’t really want you if you aren’t already famous because they’ve seen years of authors sitting behind a table loaded with their books, and almost nobody attending or purchasing.

Therefore, it is hard to set up a book tour; it takes time and persistence, and you need to begin at least three months before you plan to start the tour and figure you will be working on setting dates for at least two months.

Don’t expect to sell a bunch of books while on tour. The tour has several purposes:

(1) getting to know bookstore owners/employees and, more important, getting booksellers to know you;

(2) getting some readers to know you;

(3) getting your book into bookstores where the booksellers remember you and your book, and will continue to hand sell it; and

(4) selling a few books with a personal touch, and saying to each person who buys one: “If you like it, please tell your friends and family.”

My tour began with the totally naive gesture of me purchasing airline tickets with frequent flyer miles, that put me on the East Coast for 2 weeks. The only reasons it wasn’t totally insane were: (1) frequent flyer miles; and (2) my daughter and parents reside in NY and VT respectively, and I’ll see them all for Thanksgiving. By perseverance I have managed to book nine events for the fifteen non-flight days I am here.

Not bad. Here’s how I did it:

First, my initial contacts were made by my “publicist”. The fact is, I don’t actually have a “publicist”. Unless you are published by a big house that has decided to bless your book, or have big bucks to shell out to a publicist – I’m talking $50 – $150 per hour, or in one case I know, a $10,000 flat fee – you are your own publicist by default. It is a full-time job, or as close to it as you can possibly eke out from your other remunerative activities (you have some, right? – I hope so, cause we’re all striving as writers for that mythical ten cents an hour!).

But even though you are your own publicist, that’s not good enough for the initial contact. Few bookstores want a writer who’s such a loser that they have to book their own appearance. So my small-press publisher made the initial contacts for me – mostly from a list of contacts that I generated using the internet. One great source is the American Booksellers’ Association website – they have a state-by-state, city-by-city directory of their members, hot-linked to the members’ websites.

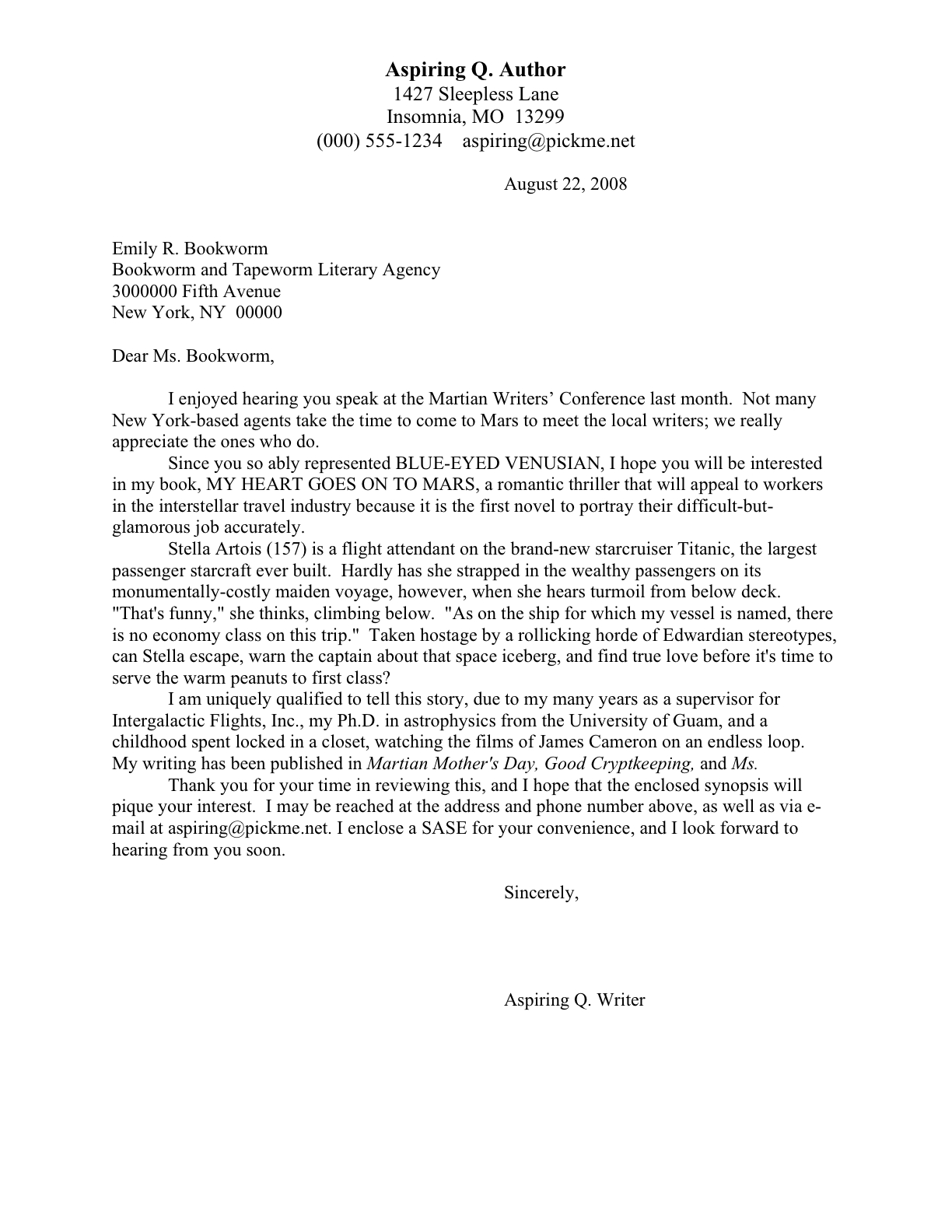

Those first contacts should be by email with detailed information (Title, Author, publisher, ISBN, cloth/trade/mass, price, where in distribution, “Please book me for an event”, when you’ll be there, contact, attached synopsis, press release, cover image, author bio). Followed the next day by a telephone call.

Once the first contacts were made by my “publicist”, it was acceptable for me to follow up. And follow up. And follow up.

Every few days I followed up and then put a new “To Do” in my computer calendar to follow up again in a few days until I finally either got: (1) booked for an event; or (2) “No.” Then I marked it in my notes, and if it was “No” I dredged up a new contact in the area (or continued to follow several in the area simultaneously).

When (not “if”) you get a “NO”, try to make it work for you. Always say that’s fine, I understand, but would you please carry my book? They’ve just said “no” to you; most people don’t like to say “no”, so now they get to say “yes, of course.” Whether they will or not, who knows? – but they’re more likely to.

One venue booked me for a big lecture, then later wrote an email saying that the lecture had to be canceled. I was very understanding, saying that just a book signing would be fine. I think they meant to cancel me completely, but now I’ve got a book signing.

Never, ever, blow your cool. Remember, we’re just writers – a dime a dozen. When you’re JA Jance there will be time enough to act the prima donna, if that’s really how you want to be remembered. But for now, nobody wants a hothead in their shop.

And besides, booksellers are some of the finest, most dedicated and underpaid people in the universe. They are there for love of books, not filthy lucre, of which there is precious little.

Even when you are booked, you are not done. You still need to follow up – check their website to be sure you are listed; if not, re-send all the info just to “help you update your events listings”; be sure they’ve got books, and there aren’t any distribution problems. Be sure they’ve got a poster if you are going to be able to send or bring one.

An example of the care and feeding the tour needs, and the need to stay cool, is the call I got from my publisher a month or so before leaving. “Congratulations,” she said, “you’ve pissed off your first Virginian!” We had discussed whether Virginians would be open to a Pacific Northwesterner messing with their history (even though it our history too!), and this seemed a portent of pitchforks to come. The ARC found its way to this bookstore’s most valued customer – a retired banker – who reported back that he was offended by my lack of respect for treasured historical figures.

I hasten to add that I love my characters, even the villains, but I don’t idolize them. Even lofty figures like John Marshall and Patrick Henry come to the page warts and all. Anyway, the owner was determined to cancel the one bookstore signing I had in Richmond (the other signing was at the John Marshall House). But another ARC and calm dialogue defused the situation, and now I count this bookseller as a colleague and Just Deceits enthusiast. And, I might add, all the other Virginians I met were very gracious and seemed genuinely interested in my book.

In addition, if you want to have anybody present at the signing you have to shake the trees till the nuts fall out. Whatever publicity you can think of – postcards, emails to friends and/or groups with an interest in your subject, small newpaper ads or review copies, radio spots if you can get them, facebook and goodreads announcements, booktour DOT com (which I could never get to work!), skinnydip in the town fountain two nights before (leaving one day for the story to run in the local paper and for you to get out of jail).

Be creative! Getting the word out is an entire blog topic, and that’s not this blog.

Tomorrow, I’ll tell you about how to sell a book once you actually convince people to come to your book signing.