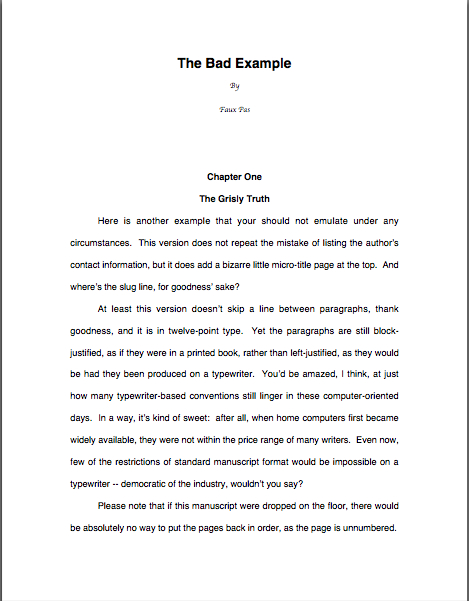

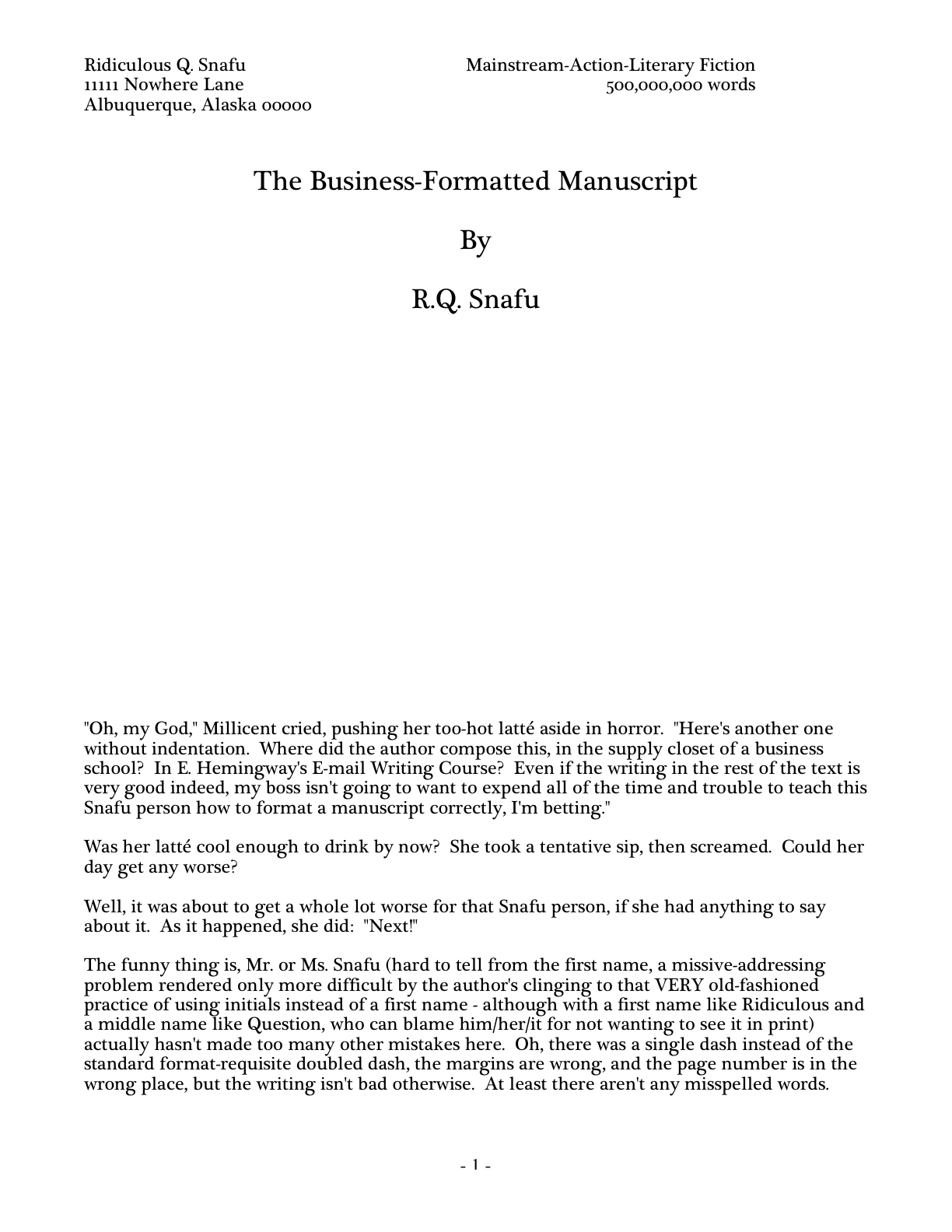

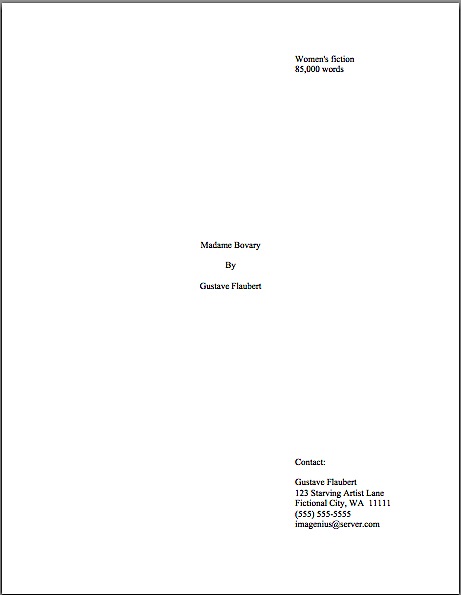

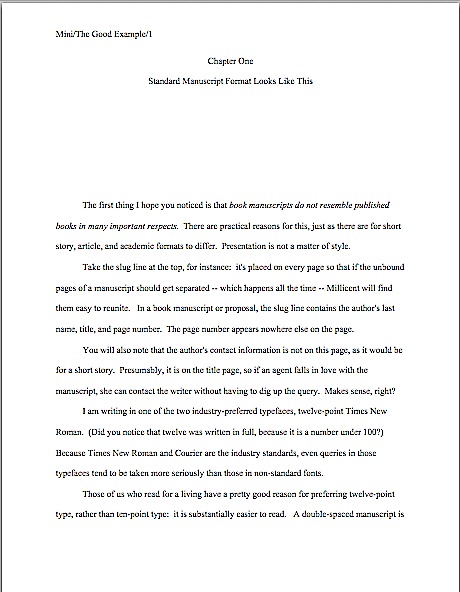

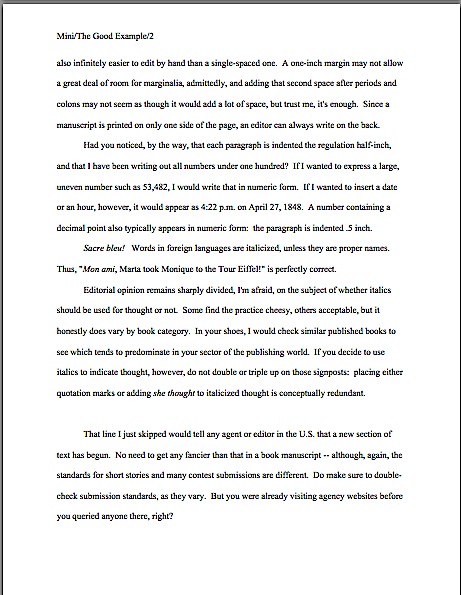

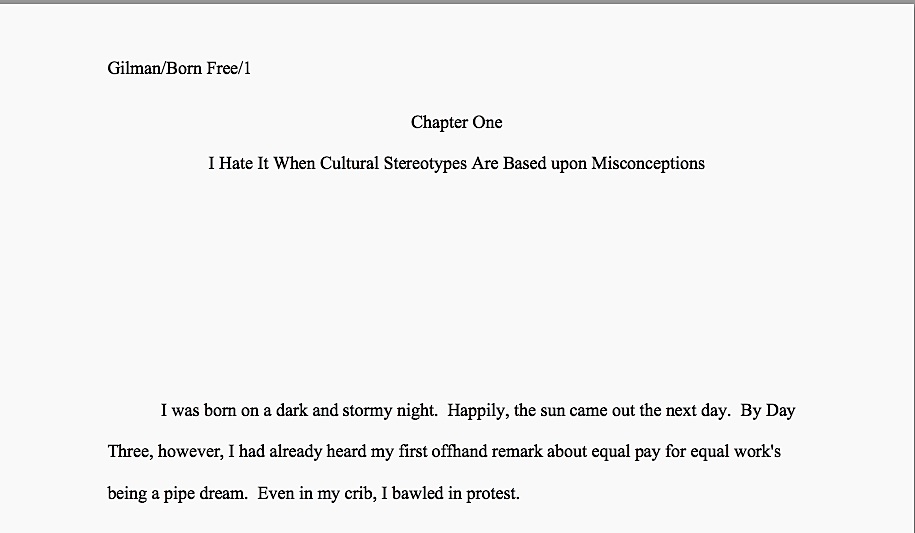

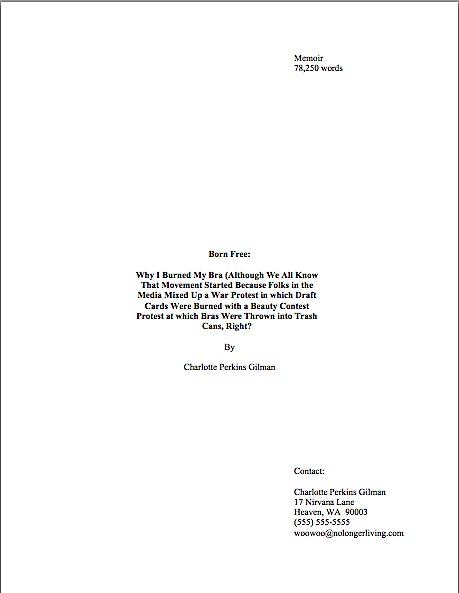

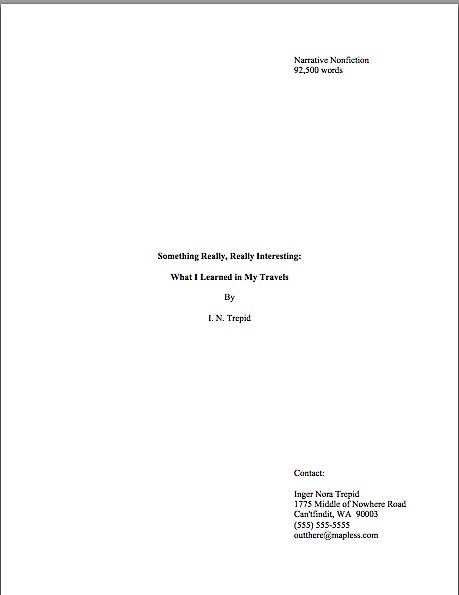

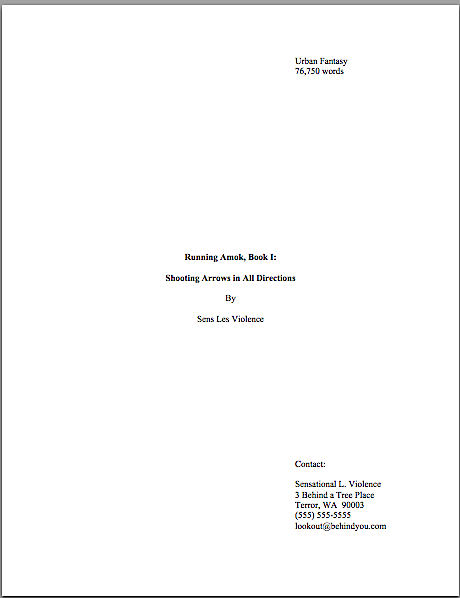

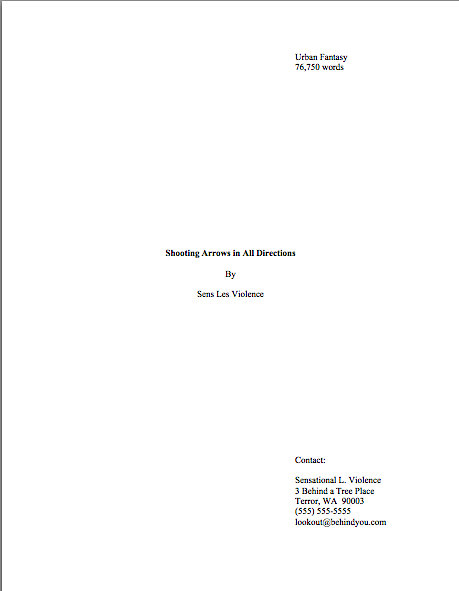

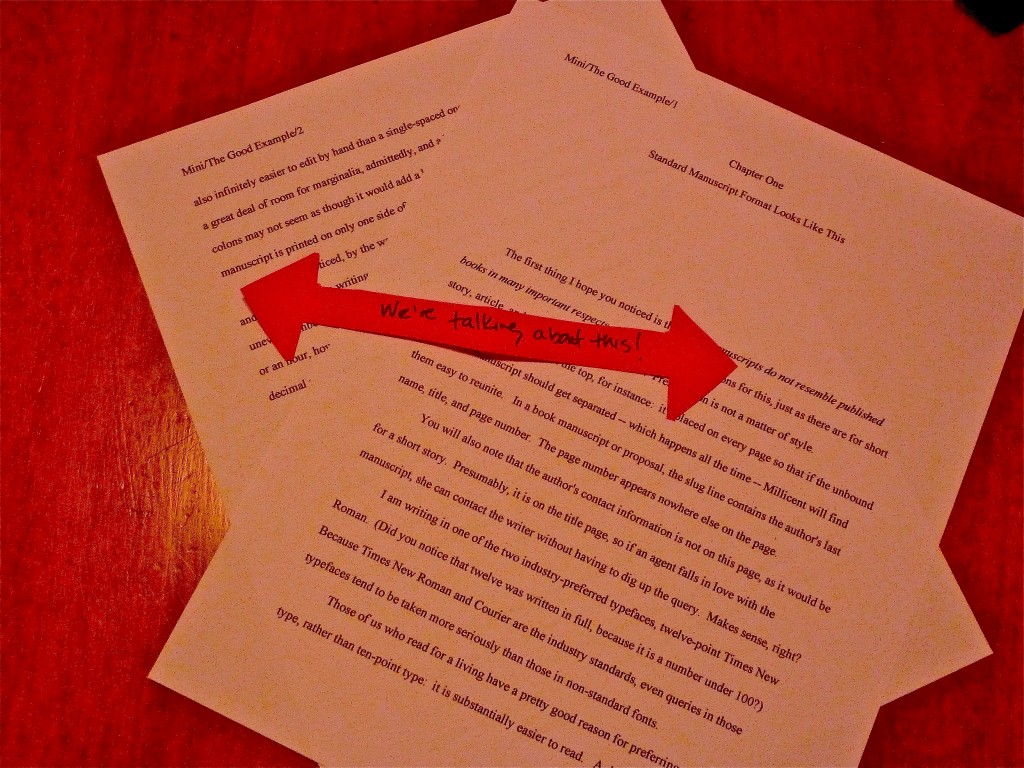

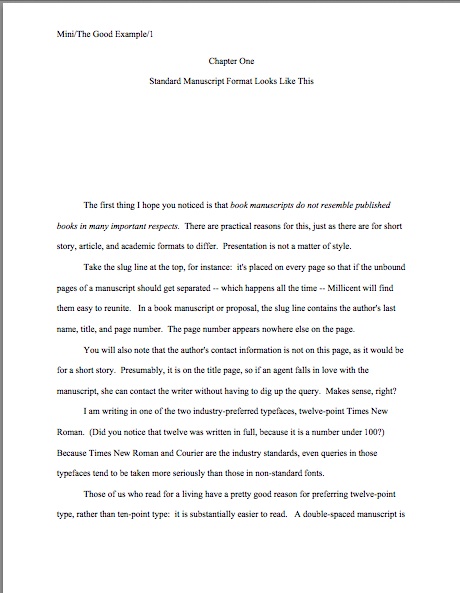

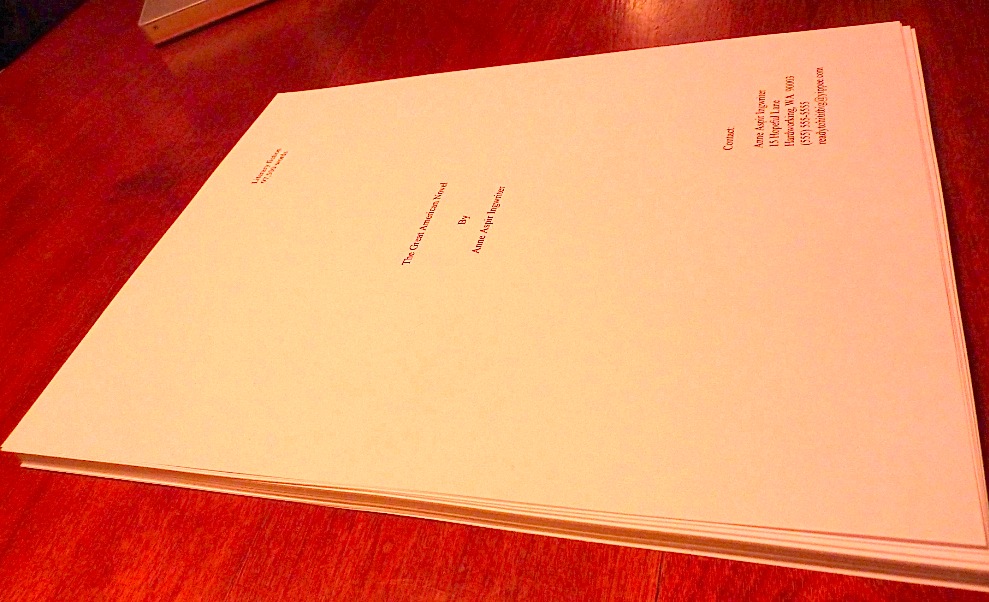

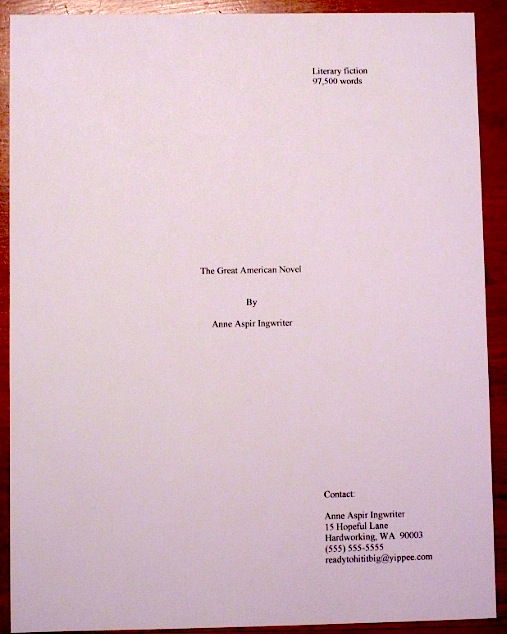

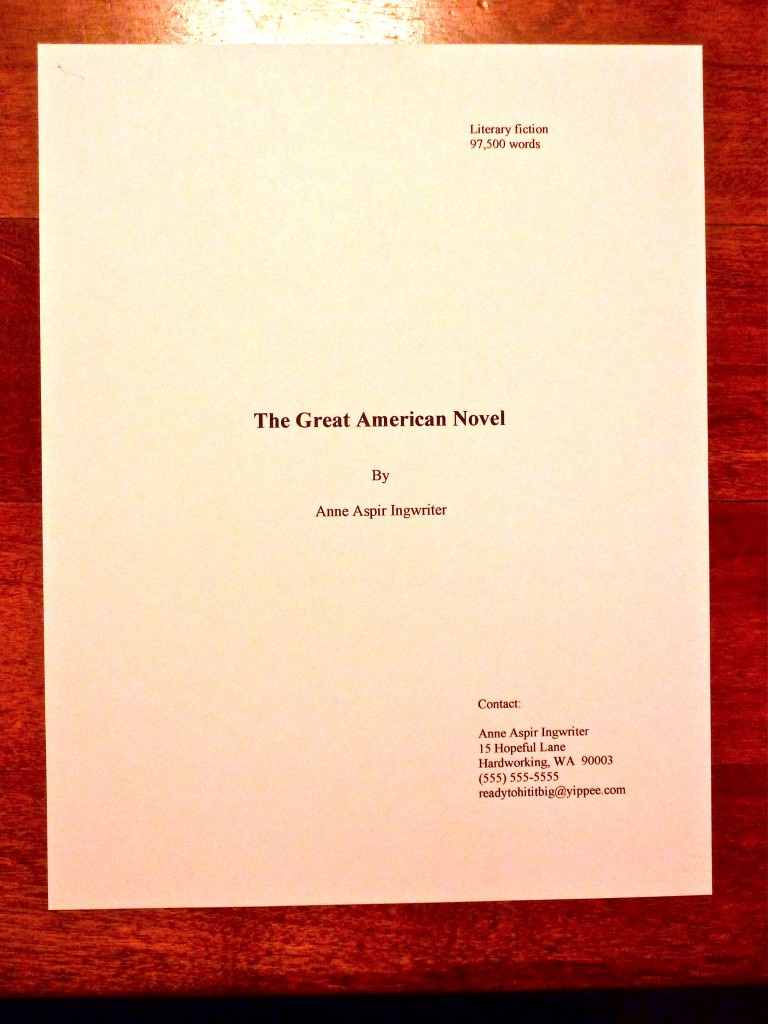

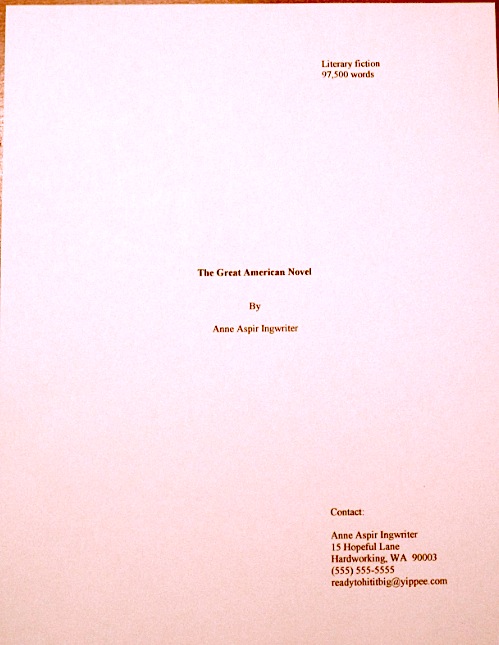

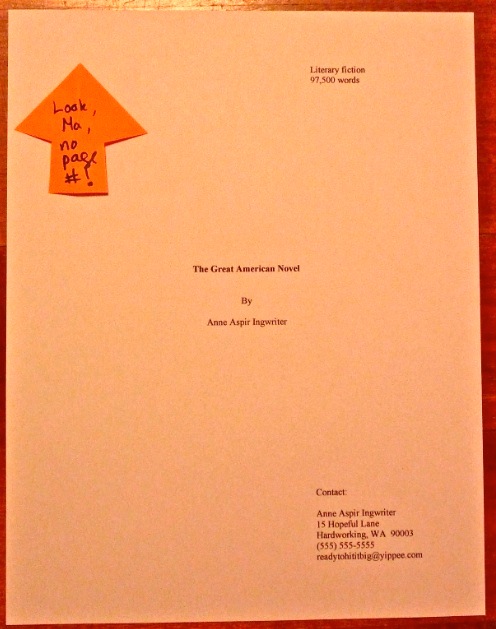

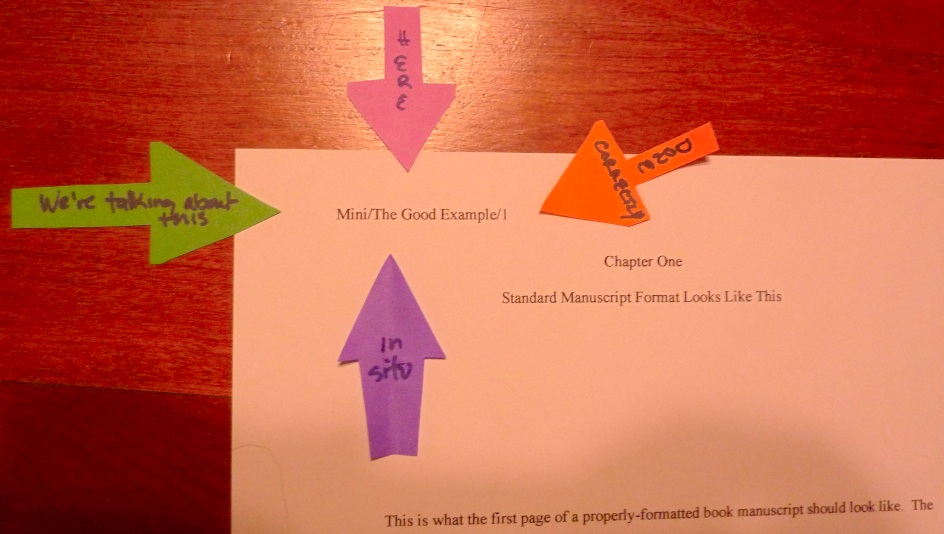

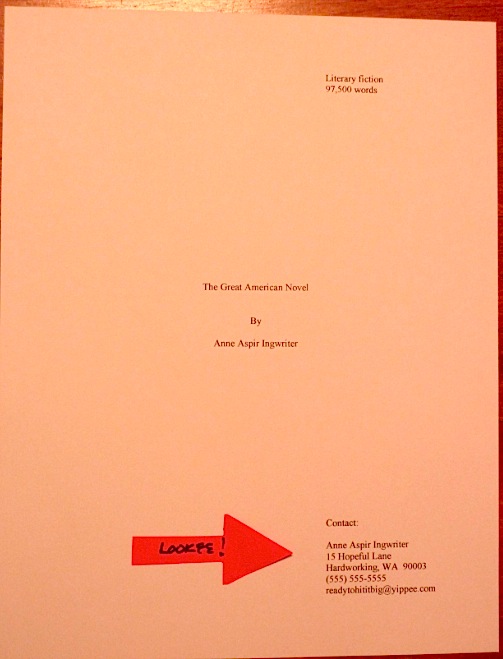

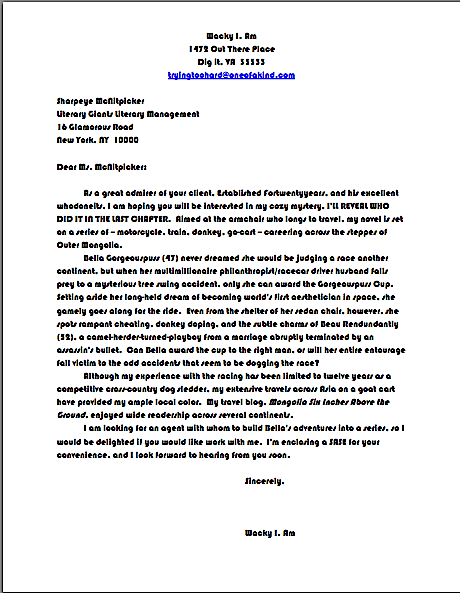

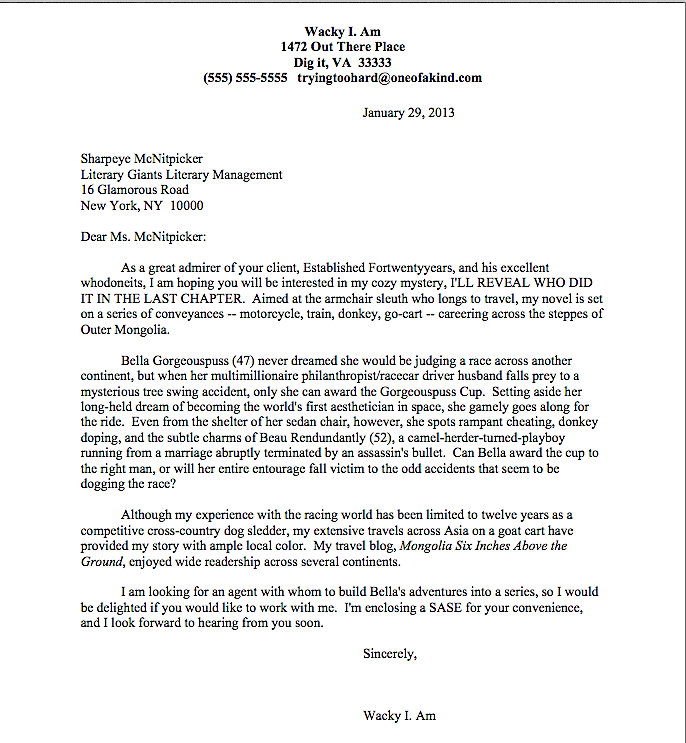

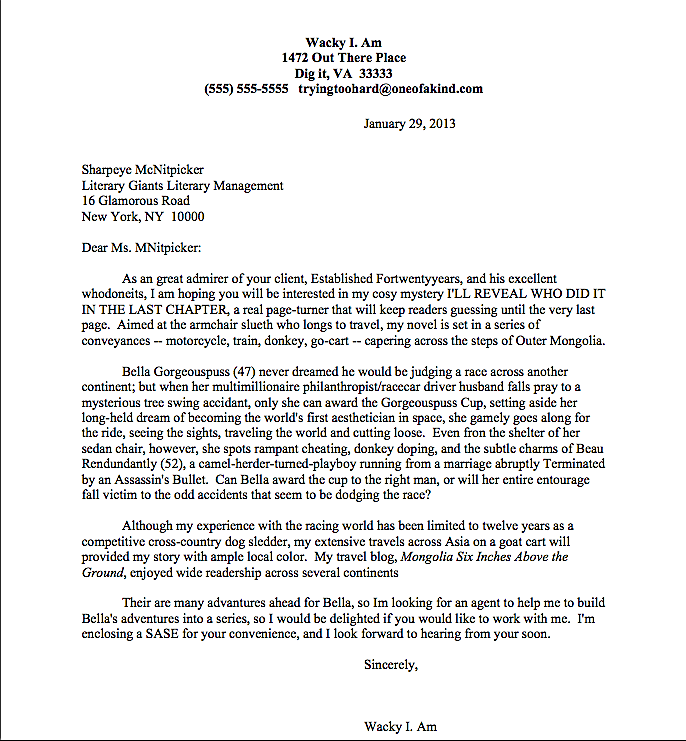

I had meant to devote my next post to showing you fine people more examples of title pages done right — and done wrong, so we could discuss the difference. Why invest the time and energy in generating both, you ask? Clearer understanding, mostly. Oh, I know that I could just slap up a single properly-formatted title page and walk away, pleased with myself for having provided guidance to writers submitting to agencies and small publishing houses; I could also, as some other blogs devoted to helping aspiring writers do, post readers’ own pages and critique them. In my long experience working with writers, established and aspiring both, however, I’ve found that talking through an array of positive and negative examples yields better results.

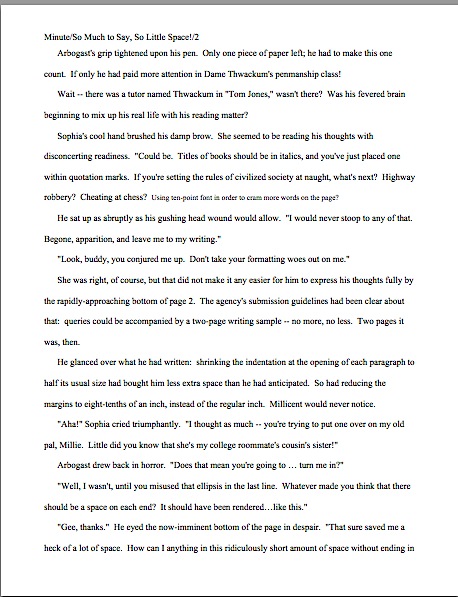

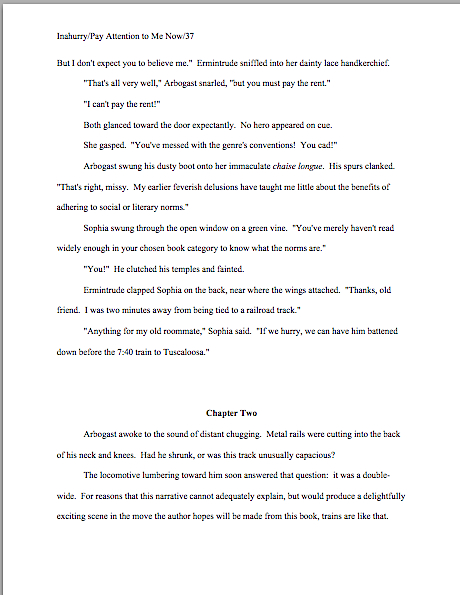

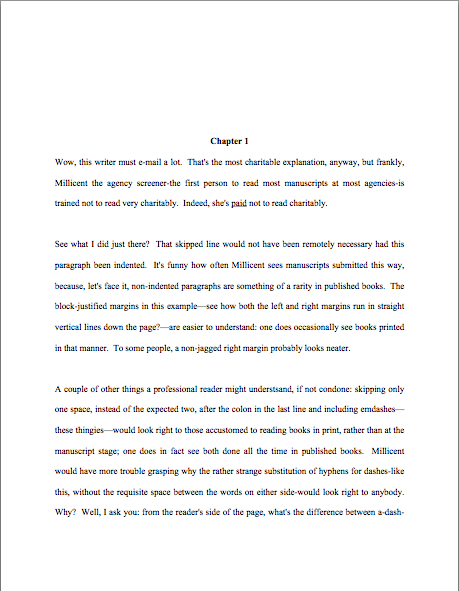

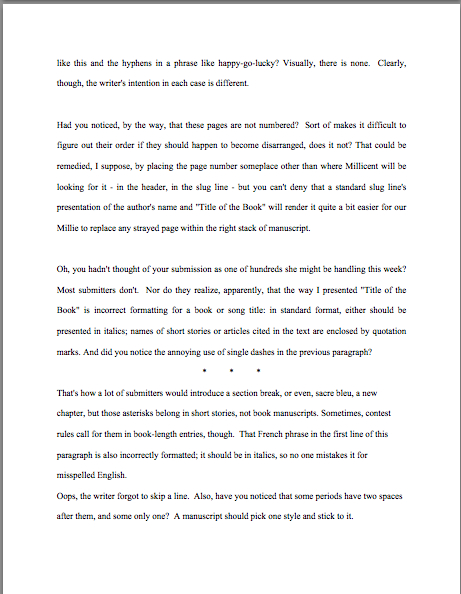

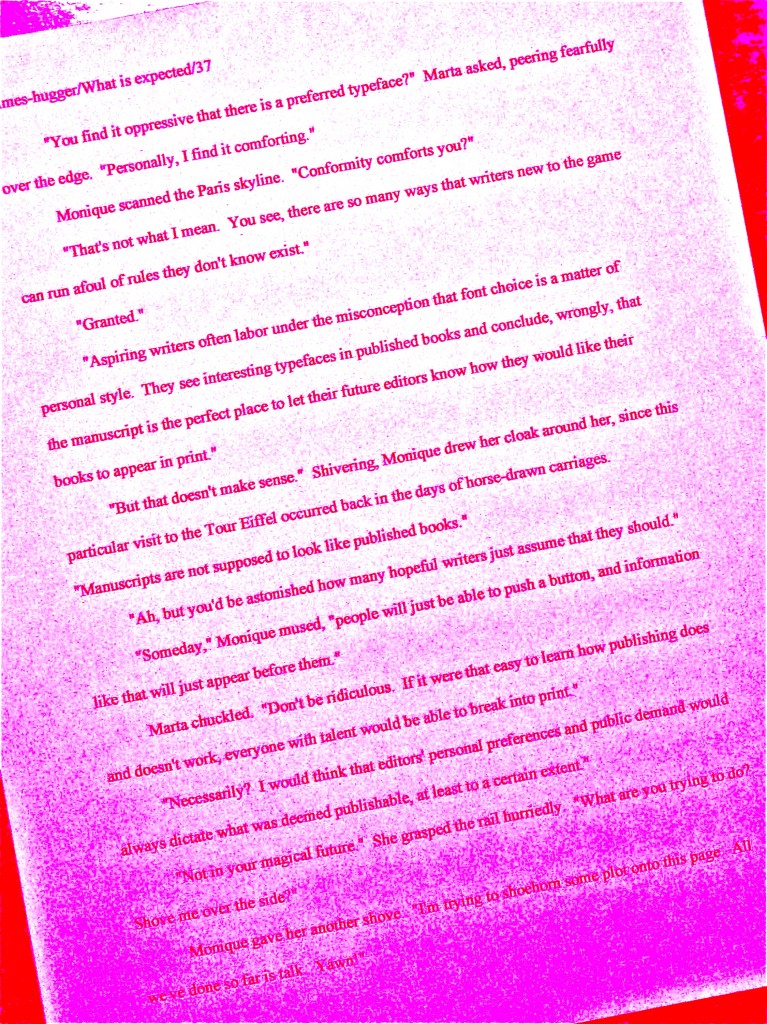

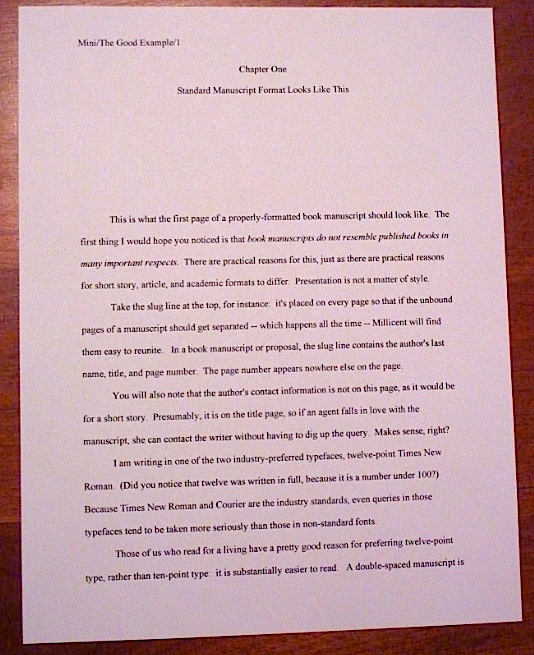

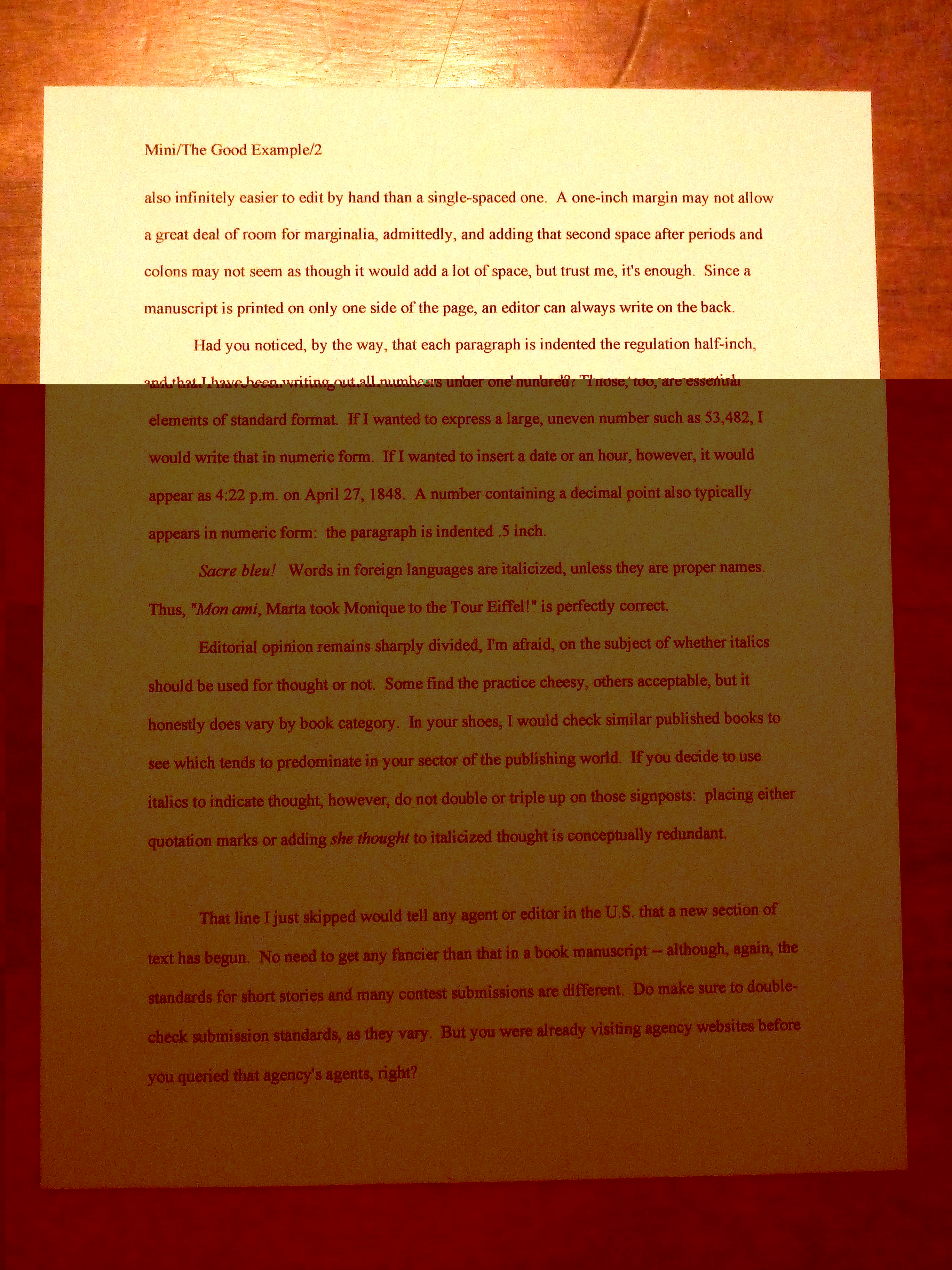

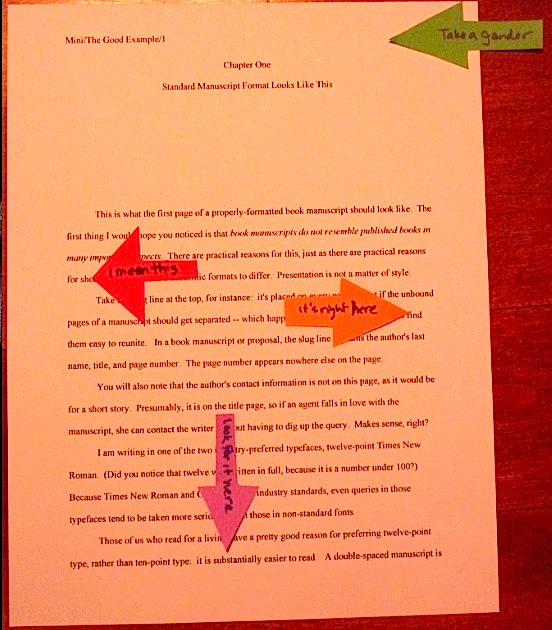

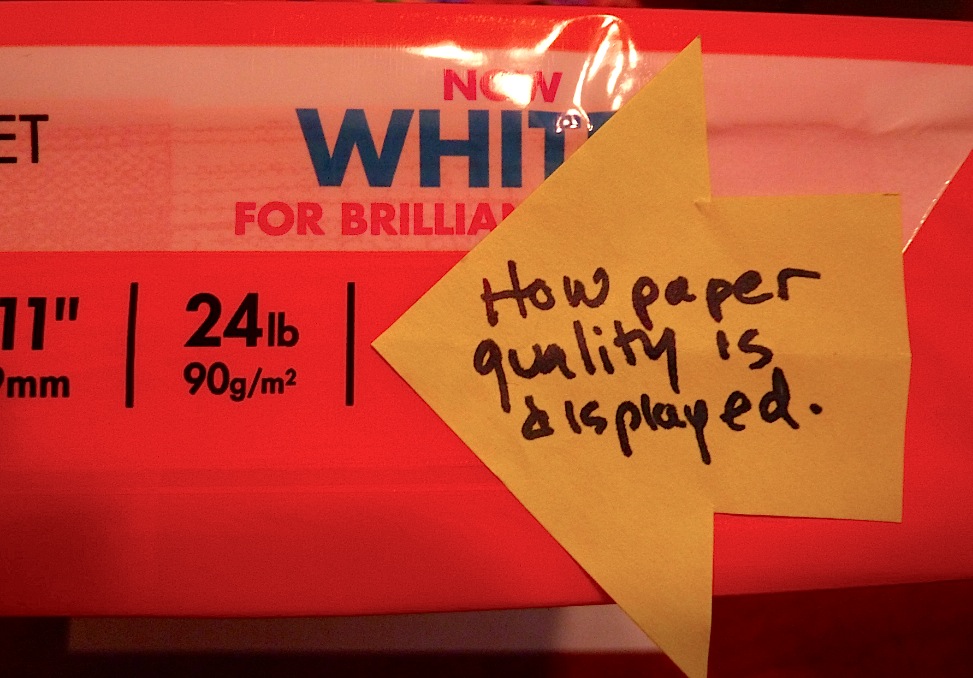

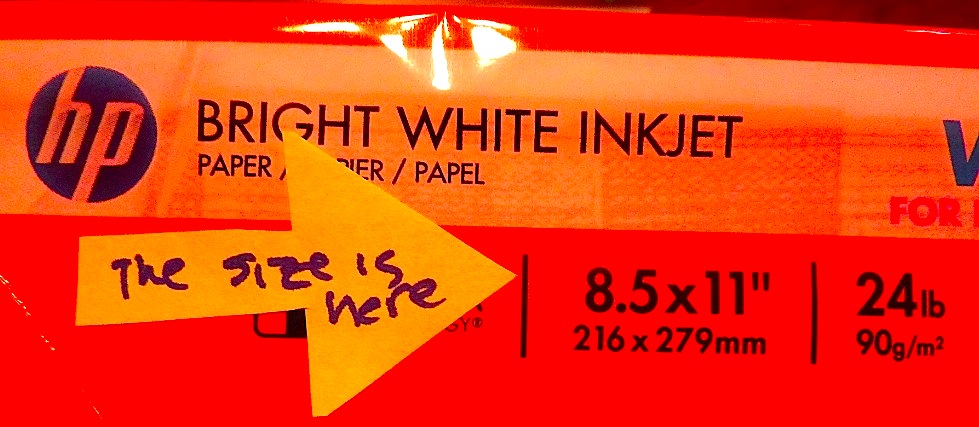

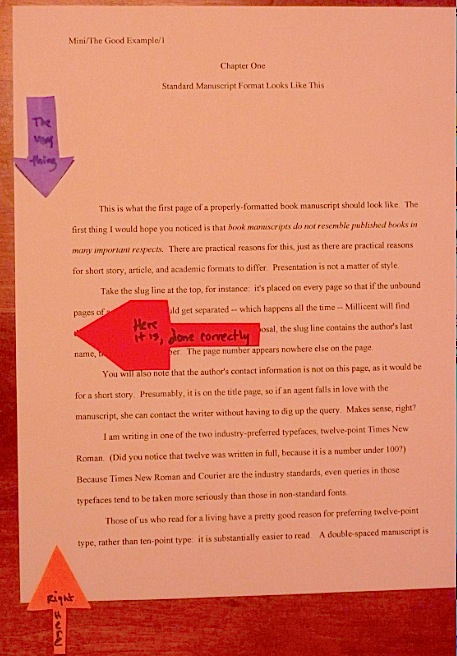

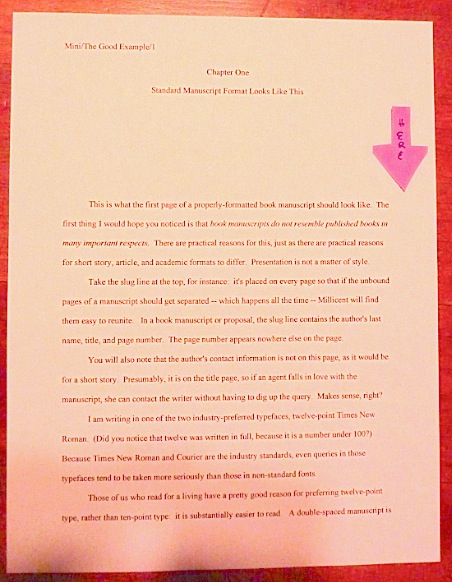

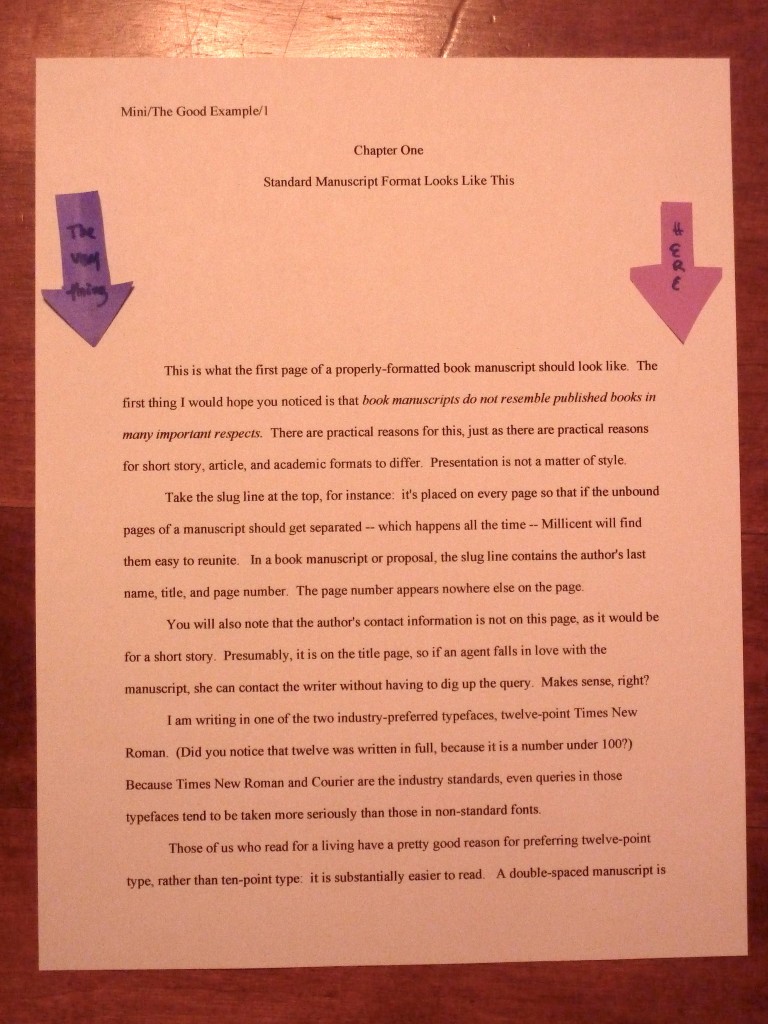

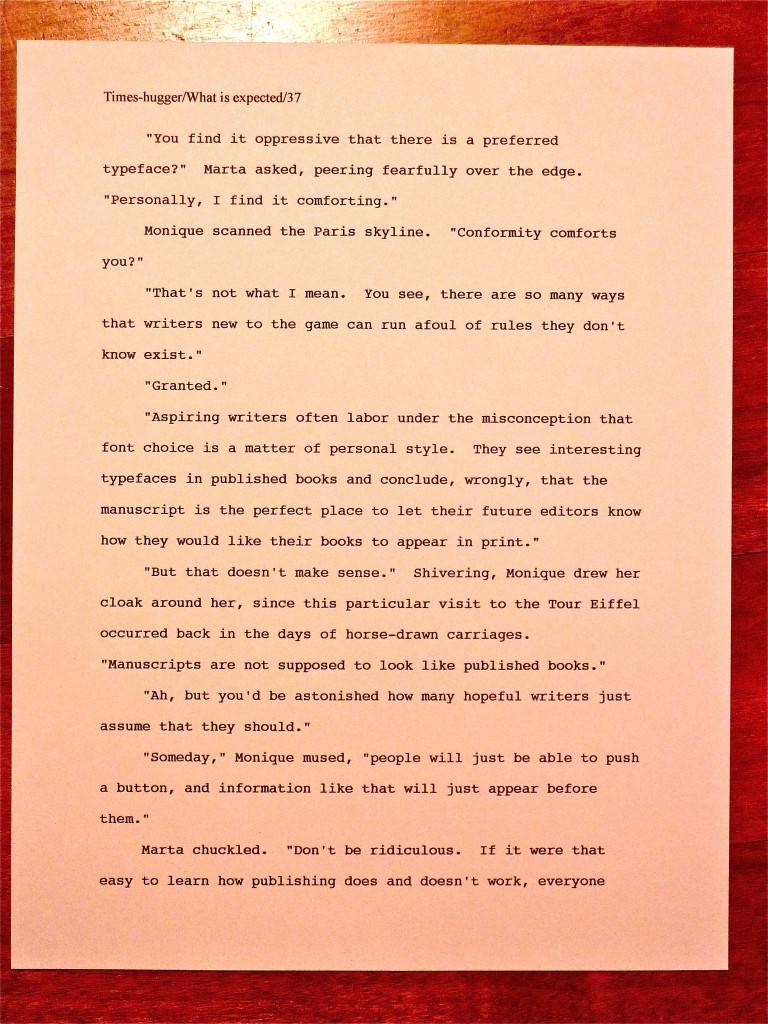

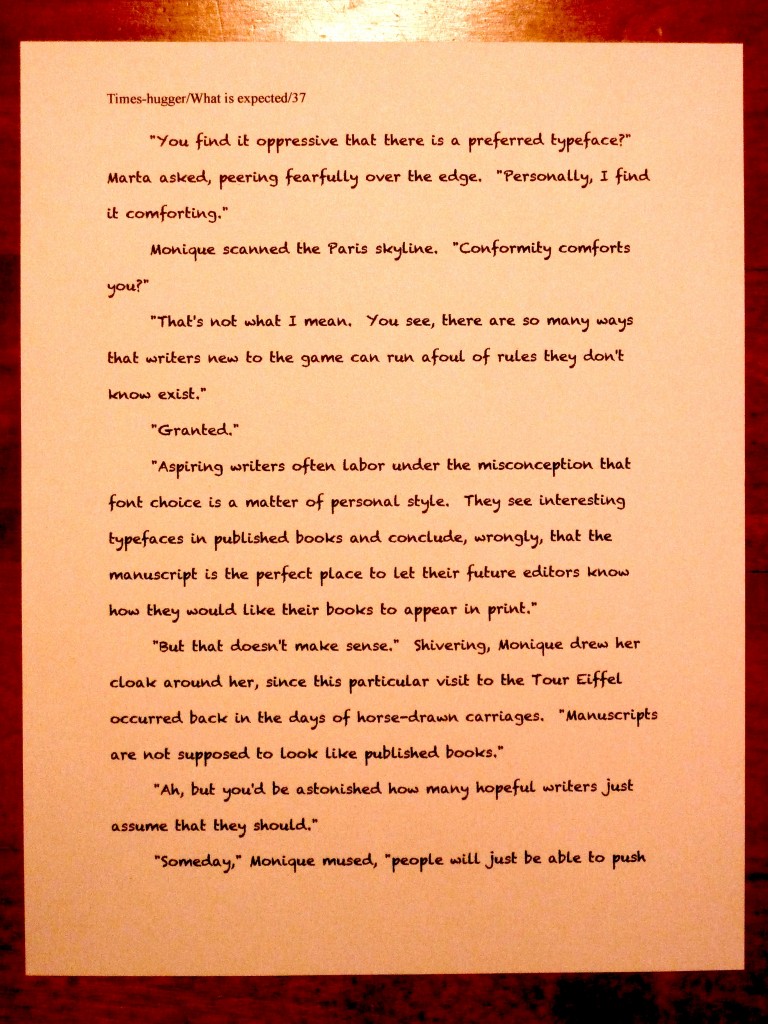

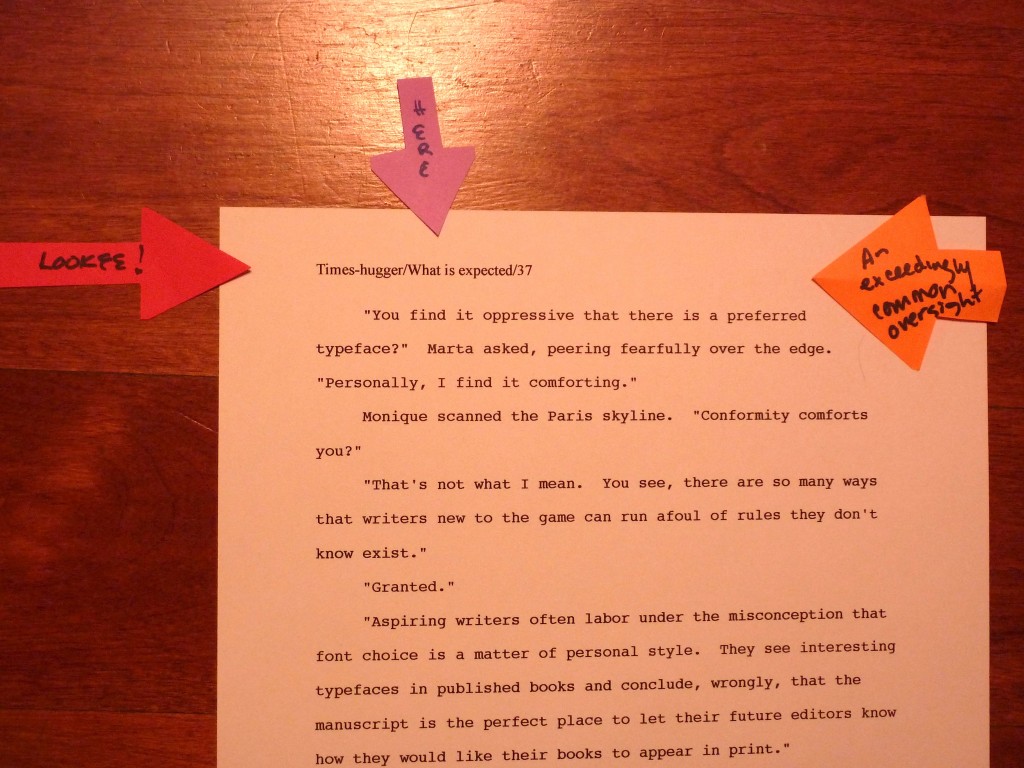

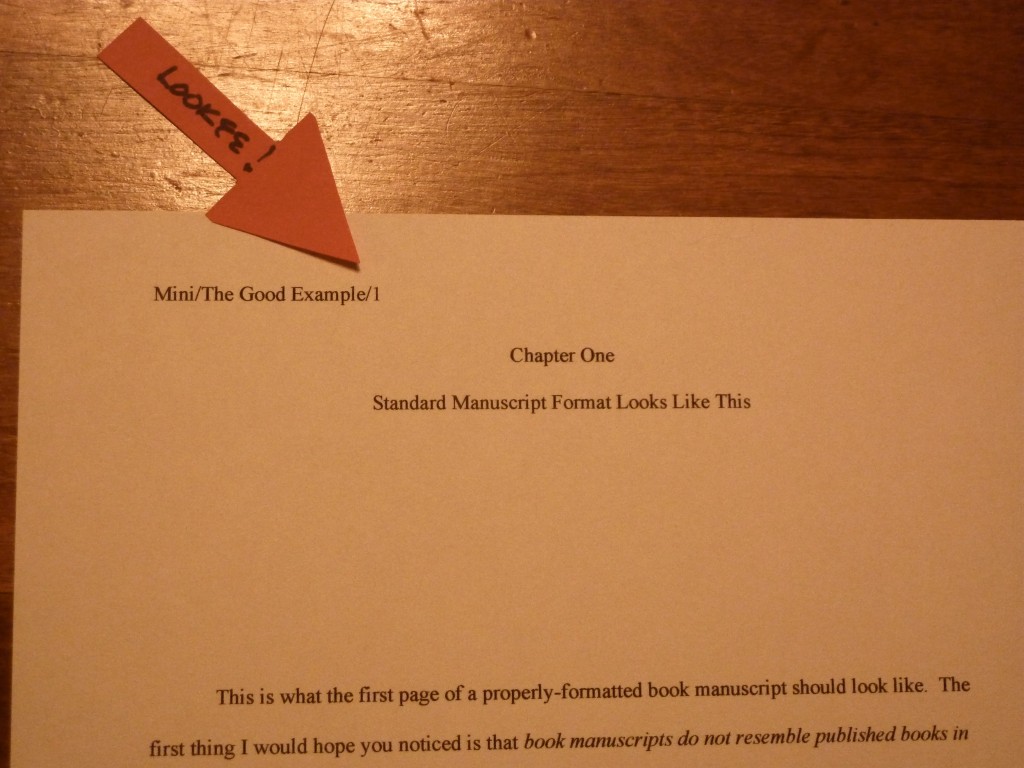

In no area of advice is this more strongly the case than in manuscript formatting. Since very few aspiring writers have had the opportunity to see a manuscript in circulation by a major agency close up, it can be quite difficult to tell whether one is following the rules — if, indeed, the submitter is aware that there are rules. Many are not. By presenting my readers with a plethora of practical examples and ample discussion, I hope to help writers new to the game avoid falling into pitfalls they might not otherwise know exist. It also enables those who have never enjoyed the inestimable advantage of having read manuscripts or contest entries on a daily basis to see first-hand just how much submission quality varies, even amongst the best-written specimens.

I sense some finely-tuned authorial antennae waving out there. Yes, novelists and other aficionados of character development?

“Is there a reason that you’re explaining this to us, Anne? Surely, by the middle of a series devoted to explaining the requirements of standard format for book manuscripts, any reader paying even the vaguest attention could be safely relied upon to have picked up on your fondness for compare-and-contrast exercises aimed at helping us develop our collective sense of what will and will not strike our old pal and nemesis, Millicent the agency screener, as professional means of presenting good writing. Heck, that would be obvious to anyone taking a casual scroll through your blog. So am I correct in picking up a subtext here?”

Well spotted, close observers of human nature: I am in fact leading up to something. And while anyone who works with manuscripts for a living could tell you that what I shall be spending the rest of this post discussing is a pitfall into which eager aspiring writers stumble all the time, sometimes at serious cost to themselves, I’m afraid that explaining what that common trap is and how to negotiate one’s way around it will require sharing an example or two that are far from pretty.

It’s been quite a while since I’ve written an industry etiquette post. I normally would not interrupt a series in progress in order to introduce one, but for the last six months or so, I, others who write online advice for writers, and even the excellent individuals toiling away in agencies have been seeing an uptick in a particular type of approach from aspiring writers. Admittedly, it’s always been common enough to drive the burn-out rate for writing gurus sky-high — in this line of endeavor, 7 1/2 years makes me a great-grandmother — yet anytime those of us still cranking out the posts start complaining about the same thing at the same time, it’s worth noting.

What’s the phenomenon? you ask with bated breath. Ah, I could tell you, but it would be easier to get why those of us behind the book scenes have been buzzing about it if I showed you. Fortunately — for discussion purposes, if not for me personally — yesterday, I received a sterling example of the breed of missives those of us in the profession often receive from total strangers, demanding attention and assistance for their writing endeavors.

Before I reveal yesterday’s communiqué in all of its glory, let’s take a moment to talk about how a savvy writer might want to go about alerting a publishing professional to the existence and many strong points of his or her book. It’s not an especially well-kept secret that, in this business, there are not all that many polite ways to go about it. If one is seeking to get a book published with a traditional large or mid-sized publishing house, one can only do so through an agency. If one is seeking an agent for that purpose, one either writes a 1-page query letter containing a specific set of information about the book or registers for a writers’ conference featuring formal pitching sessions to give at most a 2-minute description. If one wishes to work with a small publisher, one takes the time to find out what that particular publisher’s submission requirements are, then adheres to them through storm and tempest.

That’s it. Any other form of approach virtually always results in rejection. on general principle.

Why? Well, think about it: if you were an agent or editor, with which kind of writer would you prefer to work — one who has made the effort to learn the rules and follow them courteously, or one whose blustering demand for attention informs you right off the bat that, at minimum, you’re going to have to sit this writer down and explain that this is a business in which politeness counts?

Aspiring writers, especially those faced with the daunting task of contacting one of us for the first time, often find these simple strictures monumentally frustrating, if not downright perplexing. Many more regard industry etiquette as counterintuitive — or so we much surmise from the fact that the pros constantly find themselves on the receiving end of telephone calls from writers of whom they have never heard. Both agencies and publishing houses with well-advertised no unsolicited manuscripts, please policies get thousands every year. Although all of the major U.S. publishing houses have only accepted agented manuscripts for quite some time, the virtually complete disappearance of the slush pile seems not to have made the national news, if you catch my drift.

Some of you are shifting uncomfortably in your chairs, I notice. “But Anne,” a few of you on the cusp of approaching the pros for the first time murmur, “I understand that the rules of querying and submission might make life easier for agents and editors, but I’m excited about my book! I’ve worked really hard on it, and I’m impatient to see it in print. If it’s the next bestseller, I would think they would want to snap it up as quickly as possible. If it’s well-written, why would anyone in a position to publish it care how I manage to get the manuscript under their noses?”

Several reasons, actually, and very practical ones. First — and the one that most astonishes the pros that anxious aspiring writers so often don’t seem to take into consideration — literally millions of people write books every year. Many, if not most, are pretty excited when they finish them. So from the publishing world’s perspective, while it’s completely understandable, charming, and even potentially a marketing plus that a particular writer is full of vim about placing his book in front of an admiring public, it’s not a rare enough recommendation to justify tossing the rules out the window.

Second, while it pains me to say this, a writer is not always the best judge of her own book’s market-readiness; even if she were, as the industry truism goes, an author’s always the least credible reviewer of her own book. You would never know that, though, from how frequently Millicent hears from writers absolutely convinced that their efforts are uniquely qualified to grace the bestseller lists. Although the once-ubiquitous it’s a natural for Oprah! has mostly fallen out of currency, this kind of hard sell remains a not-uncommon opening for a query:

My novel, Premise Lifted from a Recent Movie, is sure to be as popular as The Da Vinci Code. Beautifully written and gripping, it will bowl readers over. You’ll be sorry if you miss this one!

While it’s not completely beyond belief that this writer’s self-assessment is correct, agents and editors tend to prefer to judge manuscripts themselves. Why? Well, since so many aspiring writers begin approaching agents and publishing houses practically the instant they polish off a first draft, it’s actually pretty common for even quite well-written manuscripts with terrific premises to arrive still needing quite a bit of revision. Millicent remains perpetually astonished, for instance, at how few submitters seem to take the time to spell- and/or grammar-check their work, much less to proofread it for flow and clarity.

Oh, stop rolling your eyes: any reputable agency, much less good small publishing house or well-known literary competition, will receive enough well-written, perfectly clean manuscripts — the industry’s term for pages free of typos, dropped words, protagonists’ sisters named Audrey for three the first three chapters and Andrea thereafter, etc. — not to have to worry about rejecting those that are not quite up to that level of sheen. From an aspiring writer’s perspective, it’s an unfortunate fact of recent literary history that the rise of the personal computer has caused the sheer number of queries and submissions to increase astronomically, rendering it impossible for even the most sleep-sacrificing professional reader to read more than a small fraction of the manuscripts eagerly thrust in his general direction.

That’s why, in case you’d been wondering, any pro with more than a few months’ worth of screening experience or writing contest judging will be aware that a super-confident writer does not necessarily come bearing a manuscript that will take the literary world by storm. Indeed, one of the reasons that the query above would be rejected on sight is that supreme confidence can be an indicator that the writer in question simply isn’t all that familiar with the current book market or how books are sold. That reference to The Da Vinci Code all by itself would automatically raise Millicent’s delicate eyebrows: in publishing circles, only books released within the past five years are considered part of the current market.

Then, too, since the kind of hard sell we saw above has been a notorious agents’ pet peeve for a couple of decades now, the very fact that an aspiring writer would use it could be construed — and generally is — as evidence that she’s not done much homework on how books actually get published. The popular notion that a good book will automatically and more or less instantly attract agents’ and editors’ attention is not an accurate reflection of current publishing realities, after all. (If that comes as a surprise to you, you might want to invest a little time in reading through the posts under the aptly-named START WITH THESE POSTS IF YOU ARE BRAND-NEW TO PUBLISHING category at the top of the archive list at right.)

Why might giving the impression that one isn’t overly familiar with the proverbial ropes prove a disadvantage in a first approach to a pro? Those of you who have been following my recent series on manuscript formatting already know the answer, right? It’s less time-consuming to work with a writer to whom the ropes are already a friendly medium. And honestly, it’s not that unreasonable for Millicent to presume that if our querier above does not know that boasting about a book is not what a query is for, she might also be unaware that, say, a book manuscript should be formatted in a particular way. Or that it’s now routinely expected that since submissions must arrive at publishing houses completely clean, savvy writers will submit them to agencies already scanned for errors.

It’s not as though a busy agent would have time to reformat or proofread a new client’s work before submitting it to an editor, right? Right? Do those glazed eyes mean some of you are in shock?

I can’t say as I blame you — when the first few agencies began recommending in their submission guidelines the now rather common advice that potential clients not only proofread their manuscripts carefully, but run them by a freelance editor before even considering approaching an agent, the collective moan that rose from the admirable, hard-working aspiring writers who routinely check each and every agency’s website before submitting positively rent the cosmos in twain. It can be a big shock to a writer new to querying and submission just how fierce the competition is to land one of the very scarce new client spots on a well-established agent’s client list.

“But I wrote a good book!” they wail, and with reason. “Why does landing an agent and getting published have to be so hard?”

The aforementioned competition, mostly: it gives agencies, publishing houses, literary contests, and even good freelance editors quite a bit of incentive to read as critically as possible. Lest we forget, most queries and requested materials are not read in their entirety — as we’ve discussed, most submissions get rejected on page 1, and most queries get slipped into the no, thank you pile before the end of their opening paragraphs.

Which makes sense, right? If the opening lines contain typos, clich?s, or any of the other unfortunately common first-approach faux pas, Millicent generally just stops reading. She assumes, rightly or wrongly, that what hits her eyes initially is an accurate representation of what is to follow. That’s the norm for agents, editors, and contest judges, too: if the third paragraph of page 1 is grammatically shaky, or if the writing is unclear, it’s taken for granted that Paragraph #3 will not be the only one that could use some additional work.

That tends to come as a surprise to many, if not most, aspiring writers. The rather endearing expectation that good writing will be read with a charitable eye often crashes straight into the reality of how many queries, submissions, and/or contest entries a pro has to read in a day. Millicent can only judge writing by what’s in front of her, after all. No matter how lovely the prose may be on page 56, or how stunning the imagery on page 312, if page 1 isn’t sufficiently polished, she’s going to make up her mind before she has a chance to admire what may come later in the book.

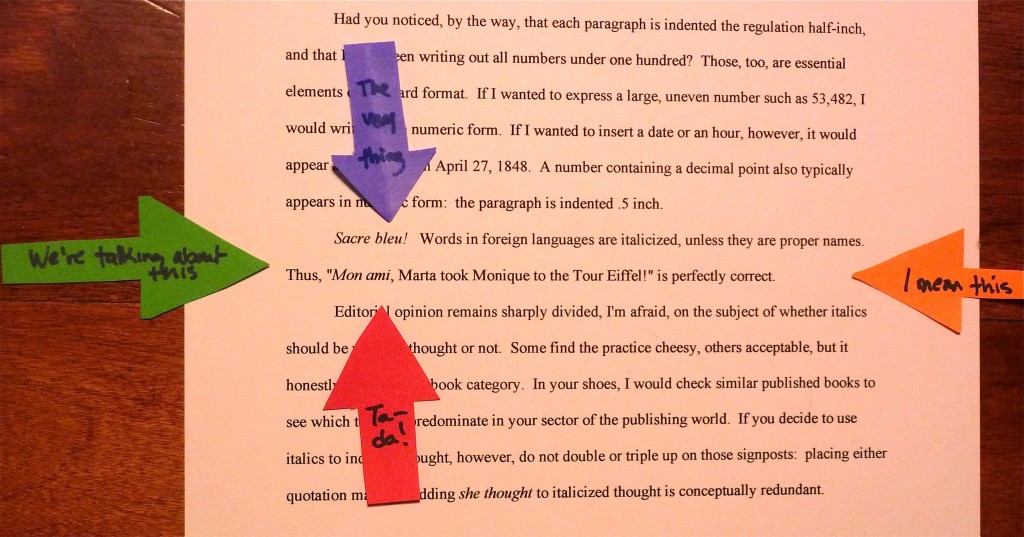

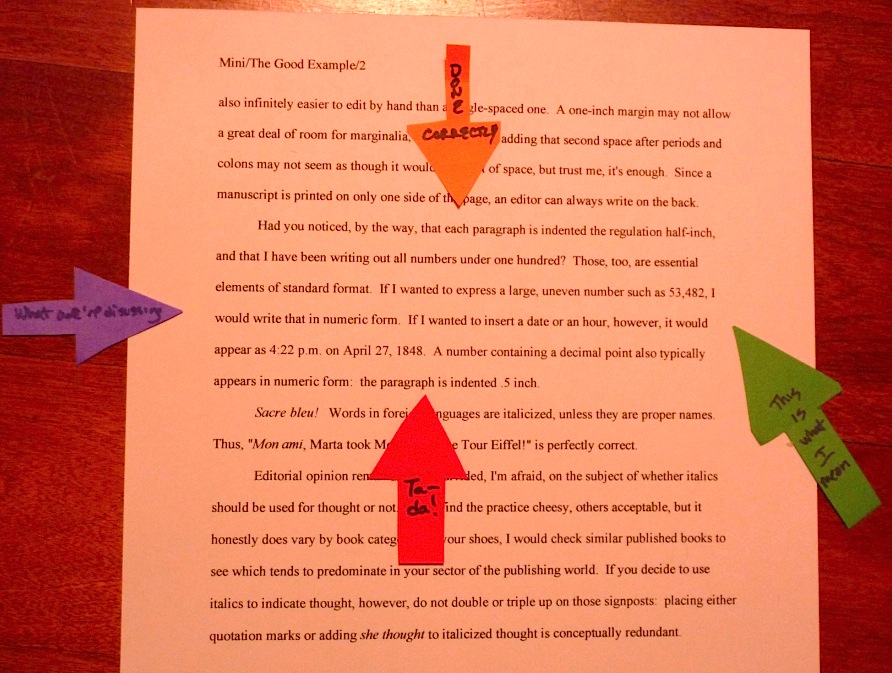

The same logic applies to the tone and consideration of the initial approach. If a writer observes the prevailing norms of publishing world etiquette — by, say, e-mailing a query rather than cold-calling the agent or adhering to a small publisher’s posted requirements to send a query containing specific pieces of information about the book instead of just popping an unsolicited book proposal into the mail and hoping for the best — then it’s reasonable to project that level of consideration onto any subsequent relationship, right? If, on the other hand, a writer first contacts the pro by non-standard means or, sacre bleu!, impolitely, it wouldn’t really make sense to expect rigorous rule-adherence or courtesy down the road, would it?

Oh, should I have warned you to sit down before I sprung that one?

Like most people, I suspect, agents, editors, and the people who work with them tend to prefer to devote their efforts to those who will be treat them with respect. This is a business positively stuffed to the gills with nice people. Although it may be difficult to discern from the perspective of a writer trying to break into print, most professional readers are quite aware that they are dealing with writers’ dreams — and do their best to handle them gently.

That’s why, incidentally, so many agencies and publishing houses employ kindly-worded form-letter rejections. More often than not, those sets of vague platitudes like I’m sorry, but I just didn’t fall in love with this, we regret to say that this book doesn’t meet our needs at this time, or I don’t think I can sell this in the current market are less attempts at explanation than efforts to spare feelings.

I know, I know: that’s not what it feels like to be on the receiving end of such a communication. It can be maddening not to know for sure why a query didn’t wow Millicent, or whether a submission stumbled on page 1 or page 221; being given a specific rejection reason could help one improve one’s efforts next time.

What the pros know from long, hard experience, though, and what aspiring writers may not consider, is that some rejection recipients will regard any explicitly-cited reason to turn down the book as an invitation to argue the matter further. This is an especially common reaction for conference pitchers, alas: first-time successful pitchers sometimes mistake polite professional friendliness and enthusiasm for a promising book concept for the beginning of a friendship. Or confuse “Gee, I’d like to read that — why don’t you send me the first 50 pages?” with an implicit promise of representation and/or publication.

From an agent or editor’s point of view, issuing a rejection, however regretfully, is intended to end the conversation about the book, not to prolong it. If they want you to revise and resubmit, trust me, they won’t be shy about telling you.

You may also take my word for it that no matter how excellent your case may be that s/he is in fact the perfect person to handle your book, how completely viable your plan may be to tweak the manuscript so s/he will fall in love with your protagonist, or how otherwise estimable your argument that this is indeed the next The Da Vinci Code may be, trying to talk your book into acceptance will strike the rejecter as rude. It’s just not done.

And in all probability, it won’t even be read. The agency may even have established a policy against it.

Don’t want to believe that? Completely understandable, from a writer’s point of view. An agent or editor wouldn’t have to engage in many correspondences like the following, however, to embrace such a policy with vim.

Dear Tyrone,

Thanks so much for letting me read your book proposal for a Western how-to, Log Cabin Beautiful: Arranging a Home on the Range. I’m afraid, however, that as intriguing as this book concept is, I would have a hard time convincing editors that there’s a large audience waiting for it. At best, this book would likely appeal only to a niche market.Best of luck placing it elsewhere.

Hawkeye McBestsellerspotter

Picky and Pickier Literary ManagementDear Hawkeye,

I’ve received your rejection for Log Cabin Beautiful, and I must say, I’m astonished. Perhaps living in New York has blunted your sense of just how many log cabin dwellers there actually are? It’s hardly an urban phenomenon.Please find enclosed 27 pages of statistics on the new log cabin movement. I’m returning my proposal to you, so you may have it handy if you reconsider.

Please do. I really did pour my heart into this book.

Sincerely,

Tyrone T. UmbleweedsTyrone —

I’m returning both your proposal and the accompanying startling array of supporting documentation with this letter. I’m sorry, but your book just doesn’t meet our needs at this time.

Hawkeye McBestsellerspotter

Picky and Pickier Literary ManagementDear Hawkeye,

Perhaps you didn’t really get my book’s concept. You see…

{Five pages of impassioned explanation and pleading.}

Won’t you give it a chance? Please?Sincerely,

Tyrone T. Umbleweeds{No response}

Dear Hawkeye,

Sorry for contacting you via e-mail, but my last letter to you seems to have gone astray. To continue our discussion of my book…

Time-consuming, isn’t it? Not to mention frustrating for poor Hawkeye. And in all probability, this is one of the nicer post-rejection arguments she’s had this month.

Just don’t do it. Quibbling won’t change a no into a yes, and believe me, the last thing any querier wants to be is the hero of the cautionary tale Hawkeye tells at writers’ conferences.

Should I be alarmed by how pleased some of you look? “But this is wonderful, Anne,” a tenacious few murmur. “Hawkeye answered. That must mean that she read Tyrone’s pleas, doesn’t it? And if she read them, there must have been some chance that she could have been convinced by them, right?”

Not necessarily, on that first point — and no on the second. Before any of you who happen to be particularly gifted at debate get your hopes up, it’s exceedingly rare that an agent would even glance at a follow-up letter or e-mail. They wouldn’t want to be confronted by the much more usual post-rejection response, which tends to open something like this:

Dear Idiot —

What the {profanity deleted} do you mean, you just didn’t fall in love with my book? Did you even bother to read it, you {profanity deleted} literature-hater? I’ll bet you wouldn’t know a good book if it bit you on the {profanity deleted}…

I’ll spare you the rest, but you get the picture, right? For every 1, 100, or 10,000 writers that take rejection in respectful silence, there are at least a couple who feel the need to vent their spleen. And, amazingly enough, they almost always sign their flame-mails.

Yes, really. I guess it doesn’t occur to them that people move around a lot in publishing circles. Today’s rejecting Millicent might well be tomorrow’s agent — or sitting in an editorial meeting next to an editor who wants to acquire their books the year after that.

The sad thing is, the very notion that manners might count doesn’t seem to occur to quite a few people. Perhaps that’s not entirely astonishing, given how firmly many aspiring writers reject the notion that, as I like to point out early and often, every single syllable a writer sends to anyone even vaguely affiliated with publishing will be considered a writing sample. Those who express their desires and requests in polite, conventional terms tend to get much better responses than those who do, well, anything else.

Even sadder: as anyone in the habit of receiving requests from aspiring writers could tell you, the senders sometimes don’t seem to understand that just because a certain type of phrasing or vocabulary is acceptable in social circles or on television doesn’t necessarily mean that it would be appropriate when trying to interest a publishing professional in one’s book. You wouldn’t believe how often the Millicent working for Hawkeye opens queries like this:

Hey, Hawkeye —

Since you claim on your website to be looking for literary-voiced women’s fiction focusing on strong protagonists facing offbeat challenges, why don’t you do yourself a favor and read my book, A Forceful Female Confronts Wackiness? It’s really cool, and I know you and your buddies at the agency will like it.

Millicent stopped reading just after that startlingly informal salutation, by the way. You can see that the tone is also askew thereafter, though, right? It’s the way someone might address a longtime friend, not a total stranger. And not a friend one particularly liked, apparently: what’s up with that snide since you claim… part? What could the querier possibly hope to gain by implying that Ms. McBestsellerspotter is being insincere in expressing her literary preferences?

Why, yes, it’s possible that the querier didn’t mean to imply any such thing, now that you mention it. Had I mentioned that Millicent can only judge a writer by what’s actually on the page in front of her, and that every single syllable a writer passes under a professional reader’s nose will be read as a writing sample?

What do I need to do, embroider it on a pillow?

I sense a certain amount of bemused disbelief out there. “Oh, come on, Anne,” those that pride themselves on the graceful phrasing of even their most hastily tossed-off e-mails observe. “Surely, addressing someone in a position to help get one’s book published this informally is practically unheard-of. I could see it — maybe — if the book in question was written in the same chatty voice as that query, but even then, I would assume that most writers would be too fearful of offending an agent like Hawkeye to approach her like this.”

Oh, you’d be surprised. Agents and editors who are habitually nice to writers at conferences routinely receive e-mails just like this. So do most of us who offer online advice, as it happens, particularly if we blog in a friendly, writer-sympathetic, and/or funny voices.

It is precisely because I am friendly and sympathetic to the struggles of aspiring writers that I am reproducing yesterday’s e-mail: I could give you made-up examples until the proverbial cows came home, but until one has actually seen a real, live specimen of this exceedingly common type of ill-considered approach, it can be rather hard to understand why someone who receives a lot of them might stop reading them after just a couple of lines. Or — I told you this wasn’t going to be pretty — why so many literature-loving, writer-empathizing folks in the biz eventually just give up on being nice about sharing their professional insights at all.

Naturally, I’ve changed name, title, and everything else that might allow anyone who might conceivably help the sender of this astonishing letter get published, but otherwise, our correspondence remains exactly as I first saw it. To maximize its usefulness as an example, though, I shall stop periodically to comment on where the sender’s message seems to have gone awry and how the same information could have been presented in a more publishing world-appropriate manner.

Heya Anne;

Okay, let’s stop here, and not merely because a semicolon is an odd choice in a salutation (the usual options are a comma, colon, or dash). It would have given most professional readers pause, too, not to see the necessary direct address comma: were heya actually a word, Heya, Anne would have been the correct punctuation.

Can you imagine Hawkeye or Millicent’s facial expressions, though, upon catching sight of a query opening this informally? True, I write a chatty blog, and the disembodied voices I choose to attribute to my readers do routinely address me in posts as Anne, but honestly, I’ve never met the sender before. A more conventional — and polite — salutation would have been nice.

This early in the e-mail, though, I’m willing to assume what Hawkeye or Millicent would not: “Frank” is trying to be funny. I read on.

I’ve drafted a 30,000 word treatise on {currently highly controversial political topic}. I call it Main Title-Reference to Similarly Themed Bestseller from the Late 1980s.

I’m going to stop us again. Treatise is an strange word in this context, but that’s not what would give a professional reader pause here. 30,000 words is quite a bit shorter than most political books; it’s really closer to a pamphlet. It’s also about a quarter of the length of the bestseller referenced here — which was written by a former professor of mine, as it happens, just before I took a couple of seminars with him in graduate school. So, unfortunately for Frank, he’s making this argument to someone who heard over a year’s worth of complaints by the author of the other work about how often his title got recycled.

Surprised at the coincidence? Don’t be. For decades, going into publishing has been a well-trodden path for those with graduate degrees (or partially-completed graduate degrees) who decide not to become professors. Or when professor jobs become scarce. Or when universities decide that it’s cheaper to replace retiring faculty with poorly-paid lecturers, rather than with, say, faculty.

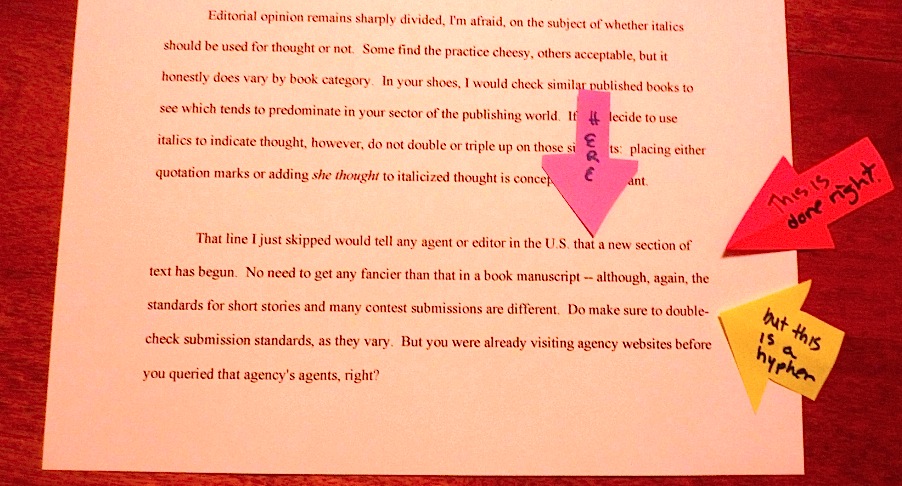

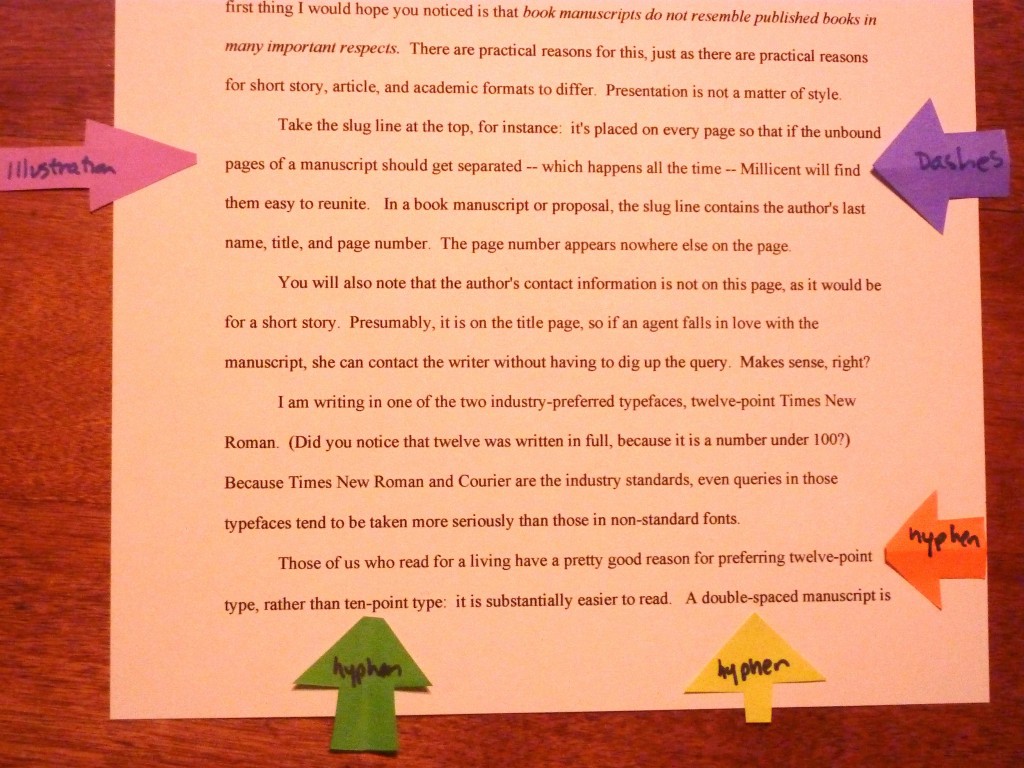

But I digress. More to our current point, this section contains a formatting problem: the hyphen used as a dash in the title would be incorrect in standard format for manuscripts, would it not? What was I saying about Millicent’s tendency to extrapolate an entire manuscript’s formatting faux pas from a slight stumble like this?

If you’ve been murmuring, “My, that’s a lot of reaction to just a few lines of an e-mail,” congratulations. You’re gaining a sense of just how closely professional readers observe every single syllable of every single piece of writing you send them. Speaking of which, let’s move on with our missive-in-progress.

It is not a rant or a historical narrative but a polemic attempt to change the rhetoric.

Sorry to have to stop us again so soon, but just so everyone knows, telling a professional reader that a manuscript is not a rant will automatically raise the suspicion that it is a rant. That’s pretty much the reaction that non-professional readers have to statements like this, too, come to think of it. Just human nature, I’m afraid.

Also, note the non-standard use of polemic. Usually, it means an aggressive attack upon somebody else’s theories. It would have been helpful if Frank had mentioned whose. Pressing on…

Scholarly in tone and temper is how it is presented but metaphors, similes, enthymemes, as well as personal observation and experiences are liberally used.

I’m rather glad that Frank decided to tell, rather than show, the “tone and temper” of his book, because talking about the language in which a manuscript is written is an exceedingly common querying mistake. A book description should aim at informing the professional reader what the book is about, not the kind of linguistic tricks the author has used to tell the tale. Think about it: why should Millicent (or I, for that matter) care that Frank is fond of metaphors, similes, or aphorisms, except insofar as they work in the manuscript itself? Wouldn’t the best — indeed, only — way to demonstrate that they do work be to show them in the writing?

Speaking of demonstrating authorial intentions, as a group, professional readers tend to be suspicious when a book description says the manuscript is written in a style not reflected in the writing of the description itself. Since this letter has not so far been written in scholarly language, the assertion that the book is carries less weight than it otherwise would.

And now that we’re at the end of Frank’s first paragraph, should we not know why he decided to contact me at all? So far, it reads like a query, but why on earth send a blogger a query? He doesn’t seem to have a blog-related question (which should have been posted as a comment on the blog, anyway, right?), nor does he appear to be seeking editorial services. Has he perhaps made the rather ubiquitous mistake of believing that anyone called an editor works at a publishing house?

No, seriously, I hear from aspiring writers laboring under this misconception all the time. Let’s read on to see if that’s what’s on Frank’s mind.

Anyway, I’ve two publishers who want me to send them my manuscript. {He names them here.} They’ve sent me forms to fill out.

Okay, so he’s sent queries to publishers, but I recognize that both of the publishers he names are self-publishing houses. Curious about whether either has recently opened a traditional publishing imprint, I checked both websites. Both offer downloadable forms, asking writers to fill them out and send them along with a manuscript or proposal.

Now I’m even more confused. Both of these printers offer editing services for self-publishing writers. So again, how would he like me to help him? Reading on…

One of the things they want is an annotated table of contents. I googled {sic} it and saw your blog.

Not entirely surprising news, as that’s a standard part of a nonfiction book proposal. As I hope every nonfiction writer reading this is aware, the archive list conveniently located at the lower right-hand corner of this page includes categories specifically aimed at assisting you in pulling together a book proposal. (You’re welcome.)

If he’s having trouble with his annotated ToC, however — which, to be fair, isn’t always easy to write — why not tell me how? Or, better still, ask a question in the comments on the relevant posts?

Or is he seeking my assistance with something else? The next couple of sentences raise a possibility that rather astonished me.

Man you write up a storm-must be one hellava typer. I can’t type worth a {profanity deleted} -my manuscript was hand written-then hunted and pecked.

More hyphens employed as dashes and other offbeat punctuation — and excuse me, but is he asking me to type his manuscript for him? Because I’m such a good little typer?

Jaw firmly dropped, I read on. The rest of the e-mail will have greater impact, I suspect, if I show it in its entirety. Or as much as I can legitimately reproduce on a family-friendly blog.

Anyway, for {profanity deleted} and giggles I just thought you might give me something to work with and/or recommend. Although they haven’t given a deadline I’ve set mine for early next month-this things {sic} been three years in the making and its {sic} time to fish or cut bait.

Thanks for your time and attention-good luck to you.

Sincerely,

Frank Lee Wantstogetpublished

I’m at a loss for words. I also still don’t know for certain why Frank contacted me in the first place — to what, I wondered, could I just thought you might give me something to work with and/or recommend possibly refer? Advice doesn’t make sense — presumably, he turned up what I had to say about annotated ToCs when he Googled the term. Or at any rate would have, had he checked out the posts under the cryptically-named ANNOTATED TABLE OF CONTENTS category on the archive list.

Here, though, is where I part company with most other professional readers. Millicent, for instance, probably would not have taken the time to ask follow-up questions if a query was unclear — or if it swore at her, for that matter. I did consider not answering it for that reason. Still, if Frank was harboring some question that he was too shy to post on the blog, I was reluctant to leave him hanging. Ditto if he just didn’t understand the difference between a freelance editor and the services for which he would be paying at either of the presses he cited.

While I was at it, I thought it might be a good idea to nudge him back toward a professional tone. As I said, it’s surprising how often writers contacting the pros don’t seem to regard it as an occasion for formal courtesy.

Hello, Mr. Wantstogetpublished —

Congratulations upon completing your book, but I’m afraid that your e-mail was a trifle unclear. Are you asking me to recommend a book on how to write a book proposal? Are you asking to book some consultation time with me on the telephone to go over the forms and how to write the annotated table of contents? Or are you looking for someone to hire to computerize your manuscript for you, since no publishing house would accept a handwritten manuscript?

If you are looking for a word processing professional, I have to say, paying a editor with a Ph.D. to do it is probably not the best use of your resources. To find someone in your area with the skills and expertise to present your manuscript professionally, you might want to call the English department at your local community college; students often are eager for this sort of work. Anyone you hire could find both the rules of manuscript formatting and visual examples on my blog.

If, on the other hand, you were asking for a book recommendation, would you mind posting that request on the blog itself? That way, my answer could be of benefit to other writers. I understand the impulse for personal behind-the-scenes contact, but part of the point of blogging is that it permits me not to have to address thousands of readers’ individual concerns one at a time.

Just so you know, though, many, many writers have used my blog’s directions on how to write a book proposal to write a successful annotated table of contents. Check the Nonfiction heading on my archive list. Should you have questions on what I recommend in those posts, please feel free to ask questions in the comments section.

That seemed to cover the bases — but see why Hawkeye and her ilk have fallen out of the habit of responding to vague e-mails like this? If the writer isn’t clear about what he wants, it takes quite a bit of time and effort to spin out a guessing-game’s worth of logical possibilities.

Another reason the pros tend to burn out on following up on these types of missives: about half the time, a thoughtful response like this will go unanswered. Then the writing guru ends up feeling a bit silly for having been nice enough to try to answer a question that was both asked in the wrong place (if the guru happens to blog, that is) and in an indistinct manner.

While I had Frank’s attention, though, there was no reason I shouldn’t try to help him become a better member of the online writing community. After politely expressing the hope that he would find the guidance he was seeking on my blog, I added:

To assist you in your publication efforts, do you mind a little free advice? People in publishing tend to judge writing quality by every single thing a writer sends them. Your e-mail contained two clich?s, something to which editors are specifically trained to respond negatively, regardless of context. You might want to choose your words with a bit more care.

Also, publishing is a formal business; manners count. It would never be appropriate to use even minor profanity in a communication with a publishing professional a writer had never met — and even if we had, it would not be advisable in an initial approach. A word to the wise.

Best of luck with your book!

Not out of line with the advice he might already have seen on the blog, right? Now, if Frank was like most aspiring writers, he would be glad of some feedback from a professional. He would also, I hoped, be pleased that I had told him where to look on my blog for writing tips. As Hawkeye and Millicent would be only too eager to tell you, however, not all aspiring writers who ask for help are particularly overjoyed to receive it.

You can see it coming, can’t you? Very well: here is Frank’s reply in its entirety. Please be kind enough to read it all the way to the end before shouting, “I told you so,” Millie.

Anne-

Your blog is-well a BLOG-its {sic} really hard to navigate and way to {sic} pedantic-as are you. Anyway my proposal letter worked! My manuscript is processed-it was drafted by hand. Oh fyi-Tolstoy re-wrote War and Peace 10 times before he submitted to the printer. Bye, Bye Ms. PHD

Well isn’t that special!

Frank Lee Wantstogetpublished

One hardly knows where to begin, does one? Leaving aside the obvious questions about why somebody who hates blogs would turn to one for advice and why one would go to the trouble of tracking down a blogger whose advice one found pedantic, I can only assume that my subtle hints about formality of tone were lost on poor Frank. And while clearly, he continues to operate under the assumption that a print-for-pay press is the same thing as a traditional publisher, he’s certainly not the only aspiring writer confused by ambiguous wording on a self-publishing site. The best of luck to him, I say.

But if typing was not what he was seeking, why did he contact me in the first place?

We shall never know. I shall limit myself, then, to observations that might help other writers. First, even if Frank found my response unhelpful, a reply that merely vented spleen served no purpose other than to burn a bridge. That made me feel sorry for him, but that would not be most pros’ reaction.

Second, if one feels compelled to cite pop culture references, do try to keep them within the current decade. Better still, avoid them entirely; by definition, quotes are not original writing, and thus not the best way to show off your unique literary voice or analytical acumen.

Third, as hard as I laughed at his evidently not having been able to come up with a stronger zinger than a reference to my degree (“You…you…educated person, you!”), it bears contemplation that the professor he admired enough to cite in his own book’s title graded me in graduate school. As I mentioned above, publishing is stuffed to bursting with former academics; an aspiring writer can never be sure on a first approach if, where, or with whom the publishing professional he’s asking to help him went to grad school. So if one’s tastes run to credential-bashing, a letter to someone in a position to help get a book published might not be the best venue for it.

Oh, and to address an amazingly common misconception about formal salutations: femaleness is not a universal solvent of credentials. If one wishes to address any holder of an earned doctorate formally, the letter should open Dear Dr. X, regardless of whether the recipient is a man or a woman.

Above all, though, if you decide to make direct contact with anyone who works in publishing, do be polite — and do be clear about what kind of favor you’re asking, if you’re writing anything but what Millicent would expect to see in a garden-variety query. Remember, answering aspiring writers’ questions is not part of most professional readers’ job descriptions: agents make their living representing their already-signed writers, just as editors make theirs handling manuscripts and guiding them to publication. Most of the time, it’s entirely up to the recipient whether to respond to such non-standard approaches or not.

Your mother was right, you know. People really will like you better if you use your manners.

Next time, we shall be delving back into the wonderful world of title page examples. Why? Because we like you. Keep up the good work!

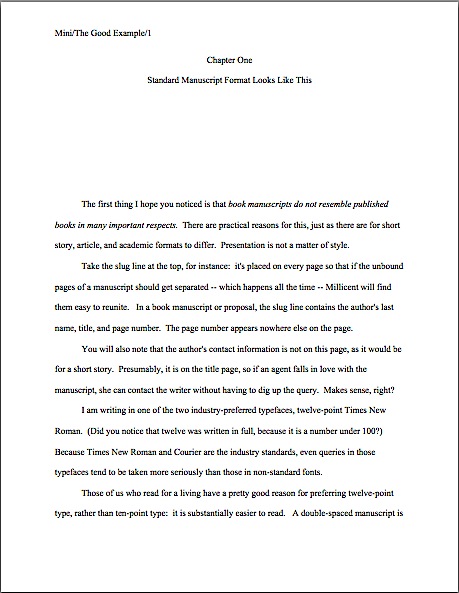

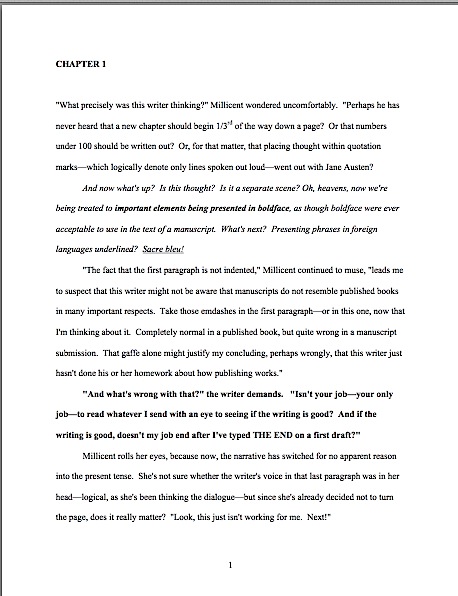

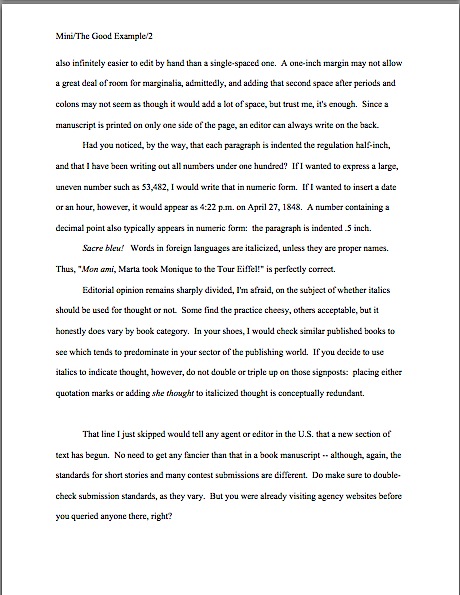

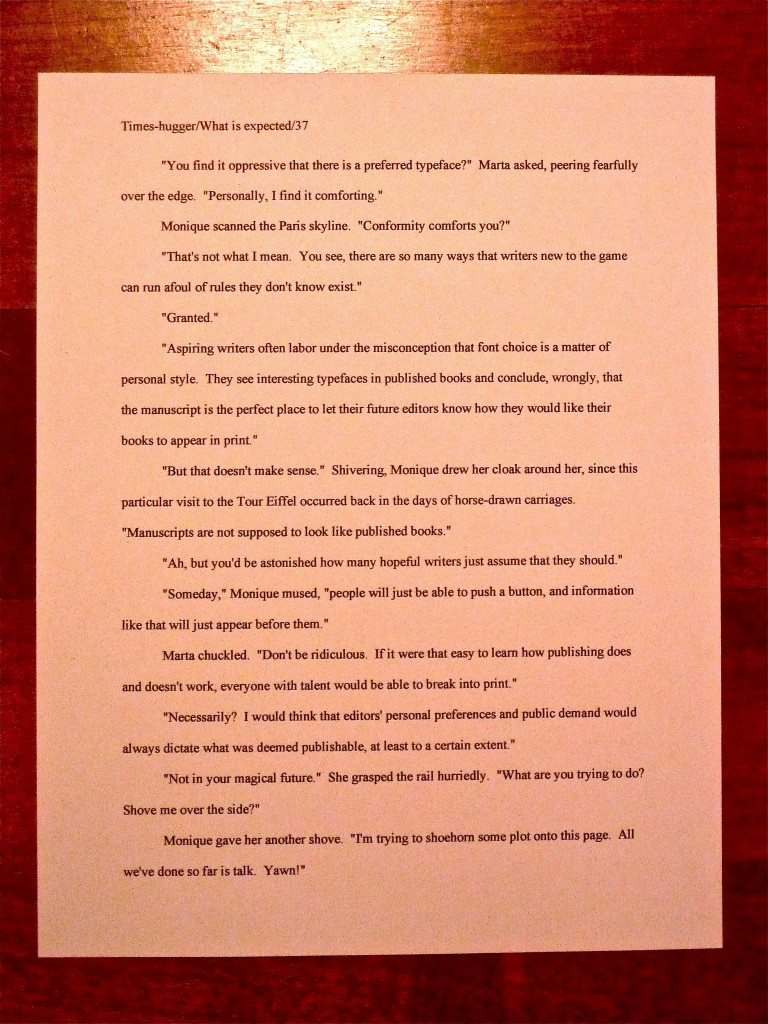

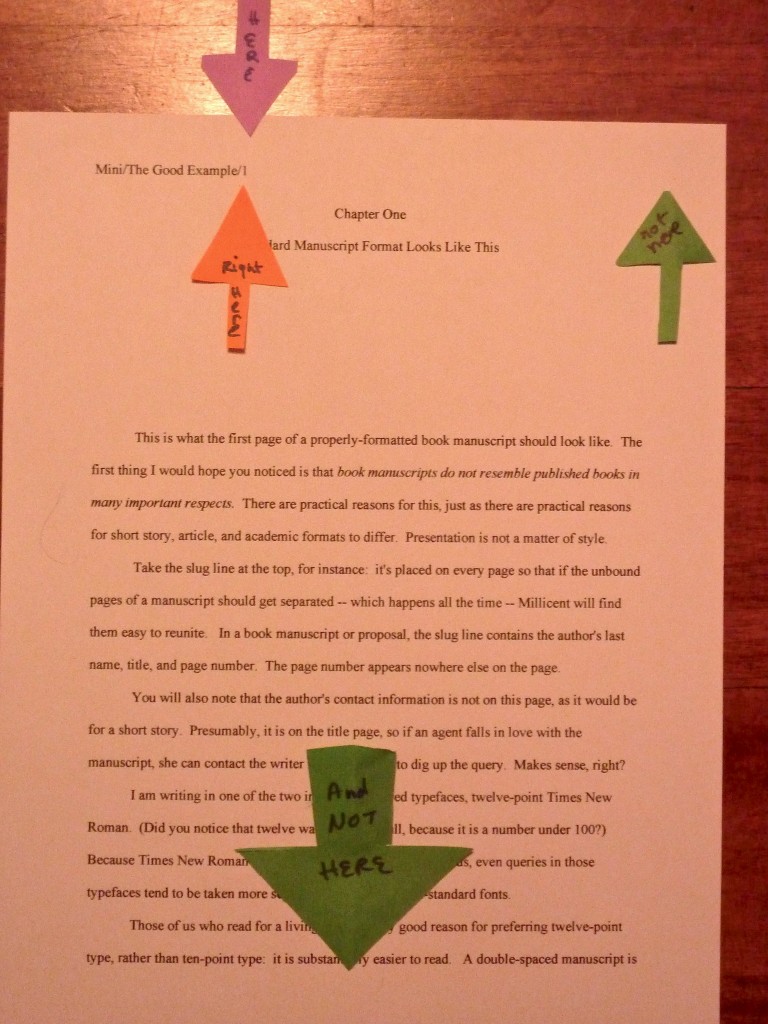

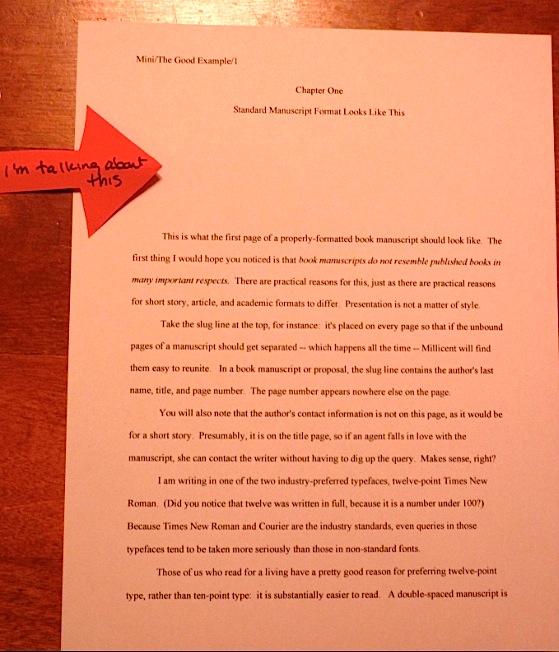

Please recognize that not everything that falls under the general rubric writing should be formatted identically. Book manuscripts should be formatted one way, short stories (to use the most commonly-encountered other set of rules) another.

Please recognize that not everything that falls under the general rubric writing should be formatted identically. Book manuscripts should be formatted one way, short stories (to use the most commonly-encountered other set of rules) another.