For those of you who are tuning in late, I’m currently in residence at an almost mind-bogglingly beautiful artists’ retreat in Southwestern France — thus all of the photos of castles and cathedrals, in case any of you have been wondering if I’d suddenly gone mad for stonemasonry. Another major result of my being here, in case you missed my announcement earlier in the week: the new deadline for the First Periodic Author! Author! Awards for Expressive Excellence has been extended to midnight on Monday, June 1.

You’re welcome.

Let me tell you, I’ve gotten some great entries, in both the Expressive Excellence and Junior Expressive Excellence categories. I’m really looking forward to running the winners here — and to hearing from more of you!

Okay, back to work. If I seem to be talking an unusual amount about cause and effect these days, blame it on the fact that this is my first retreat in a foreign land — at least in one that is not primarily English-speaking; I have retreated in Canada. I must say, I’ve been fascinated by the enlivening effect on the brain caused by switching languages between my writing time (somewhere between 8 and 12 hours per day, in case you’re curious) and out-and-about time (usually about an hour per day, with the occasional day of shopping and/or sightseeing).

While I must confess that one of the effects has been to unearth from the depths of my psyche the perfect word or phrase for the moment in Italian or Greek, another has been a much heightened awareness of how much people think while they’re speaking, even in their native tongue. It’s definitely affecting the way I write dialogue.

I’ve also become very conscious of what the French call faux amis (false friends), words and phrases that sound the same in another language, but mean something quite different in the one you happen to be speaking at the time. Take, for instance, actuellement — it seems as though it should translate as actually, doesn’t it? En fait (in fact, the phrase one uses when one means actually here), it means currently.

And don’t even get me started on the confusion if one refers to an ad as l’avertissement (warning sign) rather than as la publicité. Or if you speak of the book you’re working on as la nouvelle, which means short story, rather than as le roman, a novel.

Because so many English words are lifted from other languages, it is stuffed to the gills with les faux amis, of course, which is why it’s so difficult a language in which to become fluent. Something else a writer in English might want to take into account whilst constructing dialogue, perhaps?

Enough about false friends for the moment. Let’s move on to talking about true ones.

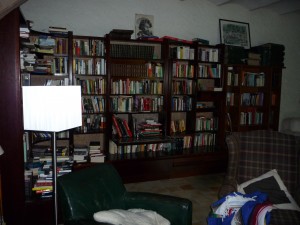

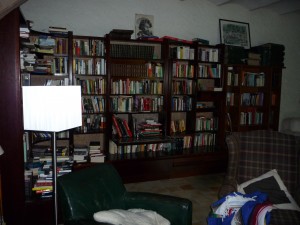

One of the great things about attending a formal writing retreat (that is, an ongoing one for which you apply) is seeing what other writers are reading. Not just the people who are in residence when you are — at La Muse, as at many retreats, that number is pretty small; actuellement, there are four writers, including myself, and two painters — but what those who have been there in the past were toting around in their bookbags.

The happy result: Boccaccio nestles next to Mary Renault and Somerset Maugham; Stan Nicholls abuts Günter Grass and Arundhati Roy. Gabriel García Márquez’ LOVE IN THE TIME OF CHOLERA stands tall next to many volumes of Isaac Bashevis Singer and an apparently misshelved copy of Adam Smith’s THE WEALTH OF NATIONS. Biographies of J.R.R. Tolkien and Charles Bukowski jostle memoirs by Billie Holiday, Roald Dahl, and INCIDENTS IN THE LIFE OF A SLAVE GIRL, WRITTEN BY HERSELF.

Combine that with what the retreat’s organizers consider essential — here, both the complete works of both Charles Dickens and William Shakespeare, as well as many bound volumes of Paris Match, as well as masses of dictionaries in four languages, an extensive array of psychological theory, and mysteriously, a guitar — and you usually find yourself presented with a pretty eclectic collection.

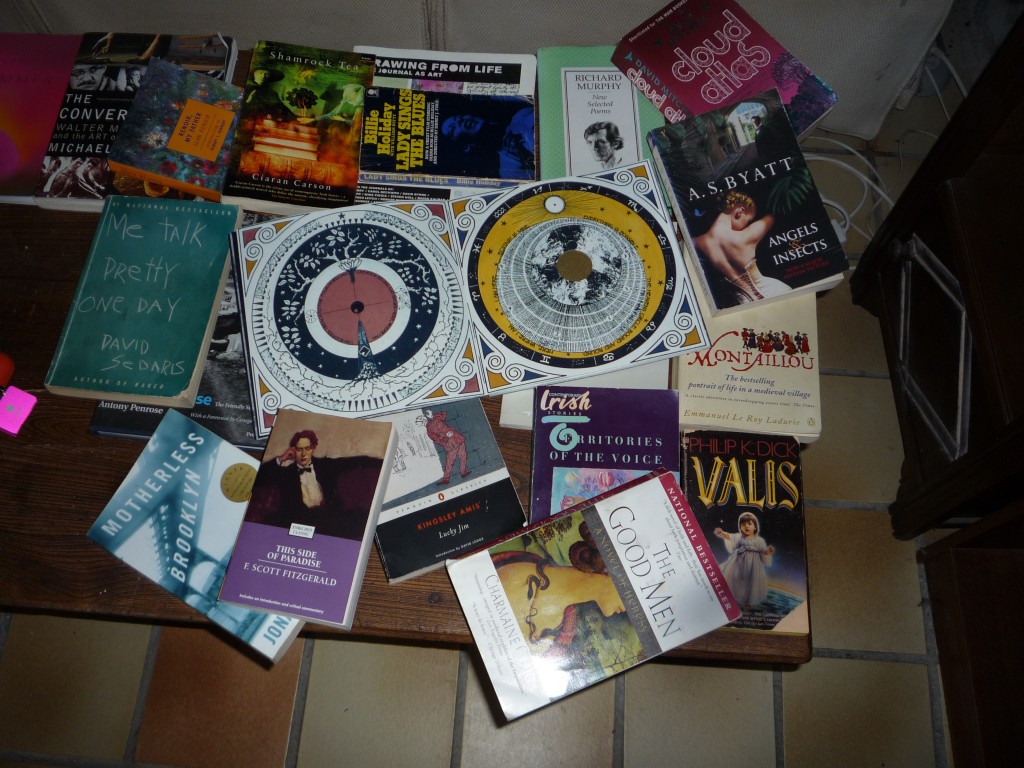

Trust me on this one: you’re going to find something interesting that you have never encountered before. Take a gander at just part of what’s here for the reading:

Yummy, eh?

As a direct and happy result of this kind of ongoing book accumulation, it’s generally well worth your while at an organized writers’ retreat to budget some fairly hefty time for reading. And not just for manuscripts in the library, either — you’re probably going to meet at least one writer with whom you would like to exchange work.

Lovely and rewarding, often, but still, time-consuming. Make sure to allot some time for it.

Truth compels me to mention, however, that actuellement, my opinion on the subject may well be colored by a fellow resident’s just having walked into the library with her thumb drive so I could download her just-this-second completed novel. (And no, this is not the first time I’ve seen someone do this at an artists’ retreat; people like to share. It’s wise to keep your writing schedule flexible enough to make field trips to admire freshly-completed sculptures and canvases upon which the paint is still wet, if you catch my drift.)

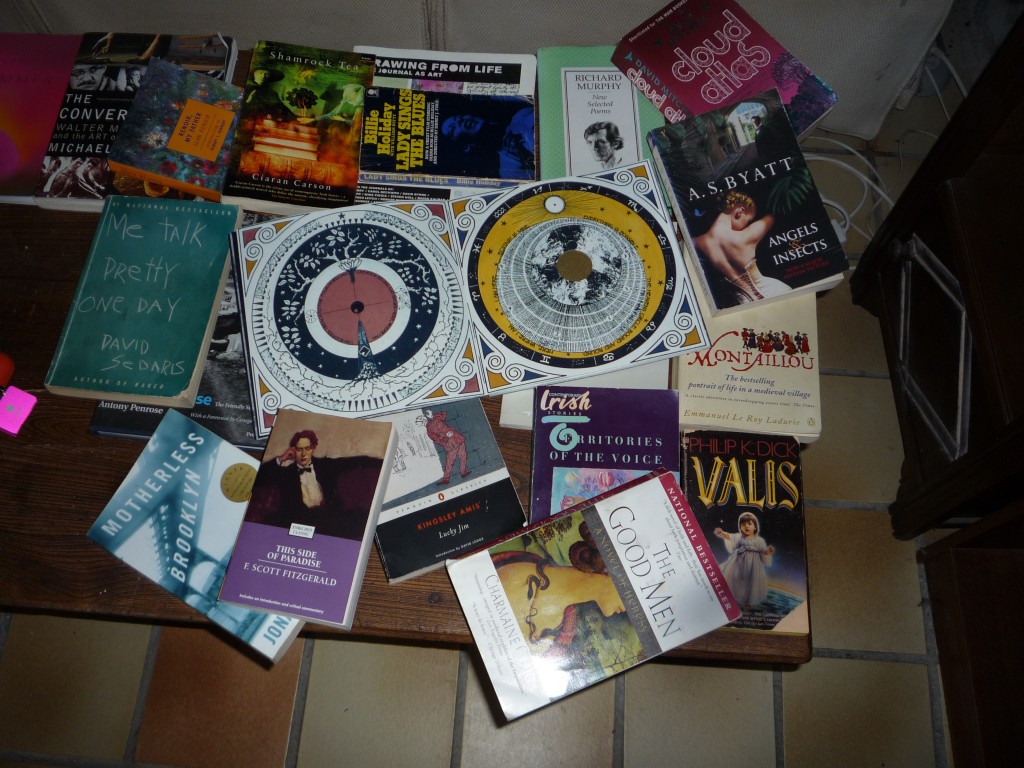

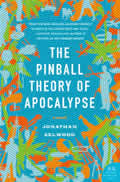

At this retreat, all attendees are asked to donate at least two volumes to the library, one that represented the kind of art we would be producing while in residence and one that reflected the part of the world that had produced us. Since I happened to know that a Seattle-based novelist had attended La Muse within the year, bringing with her the works of Garth Stein and Layne Maheu, I opted to dig deeper into my past and tote along VALIS, a largely autobiographical Philip K. Dick novel that happens to contain a scene set at my childhood home, right next to the hutch where my pet rabbits resided.

So if the moppet on the cover at the bottom right looks a trifle familiar, well, there’s a reason for that:

Yes, I’m perfectly well aware that this photo is gigantic; I wanted you to notice that glorious volume in the middle. As you may see, my contributions paled in comparison to the absolutely gorgeous hand-made book one of the painters brought, but that’s to be expected, right? (If the book-lovers out there want to see more of Nora Lee McGillivray’s astonishingly beautiful individually crafted volumes, check out her website. It will tell you which museums to visit to see them in person.)

Since I’m currently working on a novel set at my alma mater, Harvard, I also imported (literally; I had to hand-carry it through Customs) F. Scott Fitzgerald’s THIS SIDE OF PARADISE, his paean to Princeton. A fascinating novel, if you’ve never read it, the one that catapulted him to early fame. It’s far less polished than his later work, as first novels so often are; the value of repeated revision is not always apparent to the first-time author.

Which brings me to back to my subject du jour, the writer’s true and false friends, via the small miracle of having discovered in this very library a thin volume of rare nonfiction by Edith Wharton that I had never read before.

The front cover bills THE WRITING OF FICTION as “The Classic Guide to the Art of the Short Story and the Novel,” a contention which, if true, renders it even more surprising that I’d never even heard of it before. However, since the back cover’s incorrectly contends that THE AGE OF INNOCENCE, the novel for which our Edith won the Pulitzer Prize — the first woman to do so, incidentally — was her first, whereas if memory serves, THE CUSTOM OF THE COUNTRY came out a good 7 years before, and the lovely THE HOUSE OF MIRTH 15, perhaps the claim of classicism is exaggeration for marketing purposes, rather than a statement of historical fact.

THE WRITING OF FICTION is very thought-provoking, however; it’s sort of what you would have expected a grande dame of letters to have blogged about the current state of literature in 1924, had blogs existed back then.

Yet quite a lot of what she has to say remains astonishingly applicable to today’s writers. Take, for instance:

The distrust of technique and the fear of being original — both symptoms of a certain lack of creative abundance — are in truth leading to pure anarchy in fiction, and one is almost tempted to say that in certain schools formlessness is now regarded as the first condition of form.

Now, the verbiage might be a bit old-fashioned, but this is a true friend. Not entirely coincidentally, it is also sentiment that agents and editors still express at writers’ conferences all the time. They’re perpetually receiving manuscripts that lack structure, either due either to deliberate authorial choice or a writer’s lack of literary experience.

Apparently structure-less scenes containing dialogue are particularly common. Proponents of slice-of-life fiction — an approach that tends to win great applause in short stories, and thus in writing classes that focus upon short works — will frequently make the mistake of trying to make dialogue in a novel absolutely reflective of how people speak in real life.

Why might that be problematic, you ask? Well, ride a bus or sit in a café sometime and eavesdrop on everyday conversation; it’s generally very dull from a non-participant’s perspective.

More to the point, it’s often deadly on the printed page. Real-life conversation is usually repetitive, cliché-ridden, and frankly, not all that character-revealing. It requires genuine artistry, then, to reproduce it well in manuscript form.

Or, as Aunt Edith might have put it, it takes technique. For some pointers on how to put that technique in action, you might want to check out the DIALOGUE THAT RINGS TRUE and DIALOGUE THE MOVES QUICKLY categories on the archive list at right.

For the moment, I want to return to what Aunt Edith was saying. Because I know that you’re all busy people, I’ll skip her comparison of Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy (whose WAR AND PEACE, you may be amused to hear, Henry James once called, “a loose baggy monster,” speaking of structure) and move on to the next part that deals with technique:

…the novelist who would create a given group of people or portray special social conditions must be able to identify himself with them; which is a rather long way of saying that an artist must have imagination.

Not so fast there, Edith: this analogy is a false friend. I think you’re conflating empathy with one’s characters with the ability to imagine what it would like to be them, usually related but not identical phenomena. The first involves feeling for one’s characters enough to present them, if not sympathetically, then at least with fairness; the second can be purely a matter of conjecture, without necessarily involving any actual empathy with the characters at all — or, indeed, any information about how such characters in real life might actually feel or think.

Hey, if it’s purely a matter of imagination, why not just project your own feelings and thoughts onto them? Or, to fall back on my earlier example, to a reader who is already steeped in the culture you’re describing, it’s going to make a big difference whether a character within that culture says actuellement when he actually means en fait, right?

Here, imagination could lead a writer into a fairly major mistake. Another common mistake springing from relying too heavily on imagination alone — no, make that two: characters made up out of whole cloth tend to be prone to falling into stereotypes, and if the author doesn’t care about a character enough to empathize with him, why should the reader?

Ponder that last one a moment. I’ll wait.

The stereotyping problem is particularly rampant, and not just in terms of clichés. Think about how villains, or even just plain unlikable characters, tend to be portrayed in fiction — or in memoir and creative nonfiction, for that matter. One sees quite imaginative but essentially unsympathetic approaches to bad guys all the time.

And even to not-so-bad guys. Few writerly attitudes lead so surely to two-dimensional characters as the dismissive assumption that the reader isn’t going to like ‘em, anyway.

As it happens, I have a GREAT example right at my fingertips. Not long ago, a friend from my home town alerted me to the fact that a recent bestselling account of the rise and fall of a Napa Valley wine dynasty contained a rather odd reference to my late father, Norman Mini. Not all that surprising; he was, among other things, quite a well-respected winemaker descended from centuries of winemakers; it would have been rather difficult to write about enology in Northern California without at least passing reference to someone in my family.

Yet when I looked up the actual reference, it was quite apparent that his winemaking acumen had nothing to do with why the author had mentioned him: on the page, he comes across as that paragon of writerly false friends, the straw man who is mentioned only to be knocked down.

Speaking of phrases that wouldn’t translate all that well into other languages.

The funny thing is, enough of the facts in the story she tells are correct that you might actually have had to meet the man (or interview someone who had, as her website claimed she had done in some 500 instances) in order to realize just how far from the truth the book’s account is. How is that possible, you cry? Well, although the bulk of the anecdote about him is more or less as it happened, barring some easily-corrected factual errors (which is why I am not mentioning the book or the author’s name here, in order to allow her time to correct them in the next edition), the purport of the anecdote as folks in my former neck of the woods have habitually told it for the last 30 years showed him in quite a positive light, even a charming one.

As the anecdote is re-told in this book, however, he comes across as a quite sinister character.

I’m sensing some disbelief out there. “Just a moment, Anne,” come the incredulous murmurs. “Again, how is that possible, since the book in question is nonfiction? Isn’t the whole point of objective reporting to avoid this sort of contretemps? Just the facts, ma’am.”

Well, not having written the pages in question myself, I naturally cannot be absolutely sure how an ostensibly true story ended up untrue on the printed page, but my guess would be that the author relied on a false friend or two. A lack of authorial empathy, perhaps, combined with an incomplete set of facts, with the holes filled in by imagination.

What did that look like in practice? Actually, the misrepresentation was quite skillfully done: the author simply opened the anecdote by describing my father as a Napoleonic 5’4″ of bowl haircut aspiring to be taller, thereby establishing him as self-deluded. From there, all it took was some generalities about how his outspokenness rubbed a few people the wrong way to convey the impression of an abrasive, in-your-face lecturer. (Quoth my learned and soft-spoken father: “Never trust someone whom everybody likes. He’s got to be lying to someone.”) The author then went on to bolster the impression of thwarted power selective quotes from another source, something Henry Miller wrote about my father in BIG SUR AND THE ORANGES OF HIERONYMUS BOSCH.

Et violà! After such a set-up, what reader wouldn’t look upon the anecdote that followed with a jaundiced eye?

While I can think of any number of problems with this approach — up to and including the fact that I know from long extended-family experience that once a biographical untruth appears in print, it will be repeated elsewhere; lies are far more durable than truths, evidently — here are the three least contestable:

(1) my father was fully 6 feet tall;

(2) his hair was so curly that he could not possibly have achieved the haircut she described as integral to his character, and

(3) a full reading of even the page from which she had cherry-picked Miller quotes would have demonstrated clearly that the man I knew as Uncle Henry intended the passage she cited to create exactly the opposite impression in his book from what she was trying to convey in hers.

Since Edith Wharton was notoriously careful about checking factual details, I can’t believe that she would have approved, despite her quip above. Since neither my father nor our Edith are, alas, still around to defend their points of view, I naturally tracked down the author’s website and e-mailed her to point out — politely, I thought, given the provocation — that her book contained a few inaccuracies.

Her response was, at best, huffy. Her research for the book had been extensive, she explained to me so it was unlikely that she had made a mistake. In making her case that perhaps I was at fault, she cited by name three people known to me in my early childhood as The Nice Man Who Gave Me a Puppy, Mr. Bob, and That Woman Who Broke Up Mr. Bob’s Marriage as the most likely sources of, say, a misidentified photo, if indeed any misidentification had occurred. Although she was willing to believe that I hadn’t contacted her just to insult her, I really should have checked her book’s 800 notes before even considering contacting her, because any photo would probably (her word) have been cited there.

Yeah, I know — I seriously considered posting her answer in its entirety as the centerpiece about how NOT to respond to a question from a reader, ever. Simply thanking me for my note and telling me that she would look into it would have served precisely the same purpose — getting me off her back, me with my annoying propensity to regard things like height and incidents that occurred within my memory as matters upon which I have a right to express myself — without leaving me with an anecdote that any professional author would have expected me to pass along to at least a couple of other people.

The general rule of thumb for avoiding insulting one’s readers, in case you’re wondering, is that an author should ALWAYS be polite to anyone who approaches her about her book, even if she feels that the yahoo currently in front of her is being rude. Even if the author is in the right, bad word of mouth tends to spread much, much faster than “Gee, I met this author, and she was so nice.”

Human nature, I’m afraid. Just as an untruth in one biography tends to spawn repetitions in the next ten, a rebuffed reader can tell fifty potential book-buyers to stay away from that jerk — or 5,000, if he chooses to share the anecdote online. The rise of the Internet has made bad reputations much, much easier to establish.

In fairness to my rebuffer, I probably should have contacted her publisher directly about the quite easily verifiable factual errors, The extent of her research was something she also boasted about on her website, which should have placed me on guard that she might conceivably be touchy about it: as experienced nonfiction writers tend to assume that thoroughness is the minimum requirement for the job, not an additional selling point, it’s rare for the author of a nonfiction book on a not particularly contentious topic actually to list the number of interviews she conducted. In the bio on her website, no less.

All that being said, it would be easy just to write this situation off as poor research — I suspect what actually happened here is that she mistook someone else for my father in a photograph, and just didn’t bother to double-check. (There I go again, fact-hugging.) But let’s think about the writing strategy involved in producing the questionable impression on the page:

a) An author had a real-life character she wanted to use for a specific purpose in her book. In order to make that character come to life, she uses her imagination. I suspect all of us can identify with that, right?

b) Because that specific purpose was negative, she chose her descriptions (and, in this case, quotes) in order to bolster that effect — again, something most writers do.

c) In a search for telling details that would convey the desired impression — which, lest we forget, was necessarily a product of the writerly imagination, since the author never actually met the man she was describing — and because she was not approaching the character with empathy, she selected bits that conformed to her preconceived notion of the character. Again, this is a fairly standard writing practice.

d) Unfortunately, the research that provided those bits was insufficient, and she ran into trouble.

Obviously, this was an instance that annoyed me, as did her reaction to my pointing out the factual errors in this part of her book. (If I understood her correctly — and her response contained enough spelling and grammatical errors that I’m not sure that I did — she was trying to argue that my recollections of my father’s height were more likely to be mistaken than her research.)

But did you notice the narrative trick I employed in telling you this real-life story — one that I used to comic effect even in the last paragraph?

No? Let me be brutally honest about my writerly motivations: I was writing an anecdote about a person I have some legitimate reason to dislike, so I don’t have a lot of incentive to present her with empathy, do I? So while the facts in the anecdote are all true, my telling of them clearly reflected that dislike — and in order to make you, dear readers, dislike her, too, I used my imagination in order to create motivations for her.

Oh, all of the actions I described did in fact occur. But there is no such thing as a story that creates its own tone or word choices, is there?

Starting to get the picture?

If those of you who write memoir are shaking in your booties, you probably are. The fact is, for all of the blather about the desirability of objective distance from one’s subject, if a writer is trying to create an emotional response in the reader, objectivity is often not possible. Nor, especially in memoir, is it always desirable.

However, an ostensible just-the-facts presentation is sometimes a false friend to the reader — and to the writer as well. Yes, even in fiction: if a writer tries to scare up some empathy for even the characters the reader isn’t supposed to like, the result is usually more complex characters and better character development.

In other words, it’s a better means of creating three-dimensional characters.

Case in point: in the anecdote I told above, the characters were pretty black-and-white — the maligned late father, the unsympathetic writer. Yet had I exercised a bit more empathy toward the latter, I could have told factually the same story, yet conveyed the impression of a more well-rounded — and consequently more interesting, from the reader’s perspective — villain. Lookee:

An old friend pointed out to me that a bestselling book contained some rather odd assertions about my father. I checked, and it was true: the anecdote about him was told unsympathetically, and the physical description was so off-base that she could only have been describing someone else. She specifically said that he was eight inches shorter than he actually had been, for instance, with straight hair fashioned into a haircut that had not been fashionable since ancient Rome.

Puzzled, I contacted her and asked: was it possible that someone had misidentified a photo for her? Would she be open to correcting the factual errors in a future edition?

She responded so quickly that she must have received the message on her Blackberry. She was on a research trip for her next book, she said, and thus could not possibly check her notes to see if I was correct until she got back to her office; if my story did turn out to have merit, she would of course take steps to correct the minor errors in future editions. However, if I had troubled to check through the book’s 800 notes about her 500 interviews — a number that would have represented approximately 20% of my home town’s population at the time, incidentally — the photograph in question was doubtless referenced, so she doubted that she had any errors. She was quite sure, she concluded, that I hadn’t intended to impugn her journalistic credibility by implying that she hadn’t done her homework properly.

I was entirely mistaken about my father’s height, in other words; presumably, she had a source that had said so. Clearly, I owed her an apology for having brought any of it up at all, especially when, as the author of a single book that sold well, she is so important to the literary world that her research trips are times of well-advertised mourning in bookstores everywhere. At the very least, I should have waited until she got back.

Quite a different story, isn’t it? Yet in some ways, she’s a more effective villain in the second version than the first: by allowing some of her good points some page space, she comes across as having more complex motivations. (I also think this version is funnier, because it presents more of her response from her perspective, rather than mine.)

“Philosophy is not insensitivity,” as brilliant novelist, nonfiction writer, and inveterate fact-checker Mme. de Staël tells us. An authorial inability — or outright unwillingness — to empathize with her characters’ points of view does not always equal an admirable objectivity. Sometimes, it’s the result of a failure of imagination, rather than a surfeit of it.

But in order to create well-rounded, plausible characters, whether from scratch out of one’s imagination or lifted from real life, a good writer needs both empathy and imagination.

Okay, so maybe I wanted to tell this particular story — which, as you may be able to tell by how miffed I am about it, just transpired about a week ago — more than I wanted to engage in banter with Edith Wharton. As a writer, that’s certainly my prerogative: I have the power to focus my narrative in the direction that I find the most satisfying. And as a blogger, I also have the power to return to the debate with Edith in a future post. There honestly is a lot to talk about there.

Hey, the lady had some great insights into true and false friends.

Which brings me back to some semblance of my original point — believe it or not, I did have one throughout this long, wide-ranging post. First, it always behooves a writer to read widely, whether in doing manuscript research (cough, cough) or just to see how others have done what you’re trying so hard to do well. If you don’t have access to a thoughtfully-constructed, inspirational library like La Muse’s, start asking writers you respect for recommendations.

Most writers are book-lovers, after all. It’s a question that seldom fails to elicit a smile at a book signing, even from the most retiring author.

Second — and you’ve heard this one from me before — just because someone’s won a Nobel prize in literature (or has 800 notes in her bestseller) doesn’t automatically mean that everything she says in print is true. Use your own judgment, especially about writing advice.

Don’t be afraid to examine a gift horse’s dental hygiene before accepting it as your own, if you catch my drift.

Third, if you’re writing about real people, the false friend of ostensible objectivity is no excuse not to treat them with the empathy with which a good writer habitually approaches her fictional characters. Quadruple-check your facts before committing them to the printed page, and try to present even the characters you don’t like as well-rounded, plausible characters. You may even find that they work better as villains that way.

You also never know whose daughter is likely to blog about you, right?

Keep up the good work!

Following a twenty-two-year US Navy career, D. Andrew McChesney continues a passionate interest in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century naval history. Long fascinated with USS Constitution, he was privileged to be aboard “Old Ironsides” for a turn-around cruise in Boston Harbor. A tour of HMS Victory in Portsmouth, England while serving aboard USS Forrestal provides further inspiration as he crafts a series of naval adventures having fantasy elements. Beyond the Ocean’s Edge and Sailing Dangerous Waters are complete. Work is underway on Darnahsian Pirates.

Following a twenty-two-year US Navy career, D. Andrew McChesney continues a passionate interest in late eighteenth and early nineteenth century naval history. Long fascinated with USS Constitution, he was privileged to be aboard “Old Ironsides” for a turn-around cruise in Boston Harbor. A tour of HMS Victory in Portsmouth, England while serving aboard USS Forrestal provides further inspiration as he crafts a series of naval adventures having fantasy elements. Beyond the Ocean’s Edge and Sailing Dangerous Waters are complete. Work is underway on Darnahsian Pirates.

Auburn McCanta is a Pacific Northwest girl gone south. After growing up literally surrounded by her mother’s prized Portland roses, McCanta now lives in Phoenix with her husband, one Golden Retriever and one impossible Labradoodle. She’s become accustomed to the Sonoran Desert with its occasional neighborhood coyote and scorpion rout.

Auburn McCanta is a Pacific Northwest girl gone south. After growing up literally surrounded by her mother’s prized Portland roses, McCanta now lives in Phoenix with her husband, one Golden Retriever and one impossible Labradoodle. She’s become accustomed to the Sonoran Desert with its occasional neighborhood coyote and scorpion rout.

According to family lore, F. Gerard Jefferson’s claim of “always wanting to be a writer” dates back to kindergarten when, after the first day, he came home upset because he still couldn’t read. He would follow a more traditional arc after this — writing for enjoyment in spiral notebooks, becoming yearbook editor his senior year in high school, fleeing the craft because of the sobering fiscal realities of becoming an artist — but the “I still can’t read!” episode is, by far, the most telling expression for the ambition that defines F. Gerard Jefferson’s life and, hopefully, his writing.

According to family lore, F. Gerard Jefferson’s claim of “always wanting to be a writer” dates back to kindergarten when, after the first day, he came home upset because he still couldn’t read. He would follow a more traditional arc after this — writing for enjoyment in spiral notebooks, becoming yearbook editor his senior year in high school, fleeing the craft because of the sobering fiscal realities of becoming an artist — but the “I still can’t read!” episode is, by far, the most telling expression for the ambition that defines F. Gerard Jefferson’s life and, hopefully, his writing.

Rose Leonard is on the run from her life. Taking refuge in a remote island community, she cocoons herself in work, silence and solitude in a house by the sea. But she is haunted by her past, by memories and desires she’d hoped were long dead. Rose must decide whether she has in fact chosen a new life or just a different kind of death. Life and love are offered by new friends, her lonely daughter, and most of all Calum, a fragile younger man who has his own demons to exorcise. But does Rose, with her tenuous hold on life and sanity, have the courage to say yes to life and put her past behind her?

Rose Leonard is on the run from her life. Taking refuge in a remote island community, she cocoons herself in work, silence and solitude in a house by the sea. But she is haunted by her past, by memories and desires she’d hoped were long dead. Rose must decide whether she has in fact chosen a new life or just a different kind of death. Life and love are offered by new friends, her lonely daughter, and most of all Calum, a fragile younger man who has his own demons to exorcise. But does Rose, with her tenuous hold on life and sanity, have the courage to say yes to life and put her past behind her? ‘I think I was damned from birth,’ Flora said, staring vacantly into space. ‘Damned by my birth.’

‘I think I was damned from birth,’ Flora said, staring vacantly into space. ‘Damned by my birth.’ Blind since birth, widowed in her twenties, now lonely in her forties, Marianne Fraser lives in Edinburgh in elegant, angry anonymity with her sister, Louisa, a successful novelist. Marianne’s passionate nature finds solace and expression in music, a love she finds she shares with Keir, a man she encounters on her doorstep one winter’s night. Keir makes no concession to her condition. He is abrupt to the point of rudeness, and yet oddly kind. But can Marianne trust her feelings for this reclusive stranger who wants to take a blind woman to his island home on Skye, to ‘show’ her the stars?

Blind since birth, widowed in her twenties, now lonely in her forties, Marianne Fraser lives in Edinburgh in elegant, angry anonymity with her sister, Louisa, a successful novelist. Marianne’s passionate nature finds solace and expression in music, a love she finds she shares with Keir, a man she encounters on her doorstep one winter’s night. Keir makes no concession to her condition. He is abrupt to the point of rudeness, and yet oddly kind. But can Marianne trust her feelings for this reclusive stranger who wants to take a blind woman to his island home on Skye, to ‘show’ her the stars?

Linda Gillard studied Drama and German at Bristol University, then trained as an actress at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. Whilst under-employed at London’s National Theatre, Linda developed a sideline as a freelance journalist. She ran two careers concurrently for a while, then gave up acting to raise a family and write from home.

Linda Gillard studied Drama and German at Bristol University, then trained as an actress at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. Whilst under-employed at London’s National Theatre, Linda developed a sideline as a freelance journalist. She ran two careers concurrently for a while, then gave up acting to raise a family and write from home.

Those of you who were hanging around the Author! Author! virtual lounge may remember Stan from last year, when he was kind enough to visit with

Those of you who were hanging around the Author! Author! virtual lounge may remember Stan from last year, when he was kind enough to visit with  How can a man die twice?

How can a man die twice?

Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip.

Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip.

Explore the dark, rainy underbelly of one of America’s most beautiful but enigmatic cities through brand-new stories by Gigi Little, Justin Hocking, Chris A. Bolton, Jess Walter, Monica Drake, Jamie S. Rich (illustrated by Joelle Jones), Dan DeWeese, Zoe Trope, Luciana Lopez, Karen Karbo, Bill Cameron, Ariel Gore, Floyd Skloot, Megan Kruse, Kimberly Warner-Cohen, and Jonathan Selwood.

Explore the dark, rainy underbelly of one of America’s most beautiful but enigmatic cities through brand-new stories by Gigi Little, Justin Hocking, Chris A. Bolton, Jess Walter, Monica Drake, Jamie S. Rich (illustrated by Joelle Jones), Dan DeWeese, Zoe Trope, Luciana Lopez, Karen Karbo, Bill Cameron, Ariel Gore, Floyd Skloot, Megan Kruse, Kimberly Warner-Cohen, and Jonathan Selwood.

Paula Neves has been writing across genres since she was a teen, but has always loved poetry, to which she keeps returning. Her poetry has appeared in

Paula Neves has been writing across genres since she was a teen, but has always loved poetry, to which she keeps returning. Her poetry has appeared in