It’s an incredible day here at Author! Author!, campers. I believe that this is the first time in the five-year history of this blog that we have been able to follow a regular reader — a gentleman that many of you already know as inveterate commenter Shaun Attwood — all the way from writing phase to publication.

So please join me, everyone, in congratulating Shaun on today’s release of his first book, a stunning memoir entitled HARD TIME: A Brit in America’s Toughest Jail. (Mainstream Press/Random House) Kudos, Shaun!

Those of you who have been hanging around here at Author! Author! for a while may well remember Shaun from his devestating guest post last year. That post stirred huge reader response, and rightly: it told the story of a writer who felt so strongly about communicating the truth about inhumane jail conditions that he secretly wrote about them with a golf pencil sharpened on a cement wall, smuggled his pages out into the everyday world, and published it on a blog under an assumed name. Since his release, he has kept the blog going, helping other incarcerated writers get their voices heard, as well as giving talks to teenagers, encouraging them to avoid his mistakes. It is, in fact, a story of rehabilitation and redemption.

So why, given that his memoir on the subject is so enlightening about criminal justice on this side of the pond, isn’t it on bookstore shelves in the United States? Especially at a time jail conditions in Arizona have an excellent reason to be on every American’s mind?

Oh, you can buy Shaun’s memoir right now in the United Kingdom: Amazon UK was even offering free shipping within the country, last time I checked. And those of us who live close to the border could certainly pop up into Canada, or even order it à la distance from Amazon Canada.

But just walk into a brick-and-mortar bookstore in Main Street down here? No such luck.

Fortunately, those of us in the States have two options for procuring it. First, a UK online bookseller, the Book Depository, will ship Hard Time to North America for free. This is a great resource for those of us with a hankering to read books by British authors not yet widely distributed over here; I’m very pleased to be able to let my U.S. readers know about it.

The second method — and perhaps some of you saw this coming? — will be to enter the literary contest I shall be announcing in tomorrow’s post. Hey, why shouldn’t the good fortune of one member of the Author! Author! community spread joy to others?

I don’t want to distract from today’s festivities with contest details, however. I’d rather devote our time today to something I rarely do here: re-running Shaun’s extraordinary contribution to last year’s fascinating Subtle Censorship series — followed immediately by the fresh guest post he was kind enough to write for us while my hand’s been ailing.

Call it a before-and-after portrait of a memoirist — and much-appreciated proof that a good writer with a good story can indeed see his work come to publication. Take it away, Shaun!

Towards the end of my stay at the Madison Street jail in Phoenix, Arizona, I asked a guard how Sheriff Joe Arpaio got away with flagrantly violating federal law by maintaining such subhuman conditions.

“The world has no idea what really goes on in here,” he replied.

I decided that was about to change.

Some of you may be familiar with Sheriff Joe Arpaio, the star of the reality TV show, Smile…You’re Under Arrest! He’s the sheriff who feeds his prisoners green bologna, puts them to work on chain gangs, and makes them wear black-and-white bee stripes and pink underwear.

He has labelled himself “America’s toughest sheriff,” but he never mentions that he is the most sued sheriff in America due to the deaths, violence and medical negligence in a jail system subject to investigation by human rights organisations including Amnesty International and the American Civil Liberties Union.

In a maximum-security cell — about the size of a bus-stop shelter, with two steel bunks and a seatless toilet — I used a golf pencil sharpened on the cement-block wall to document the characters, cockroaches, suicide attempts, and deaths. Wearing only pink boxers, I wrote at the tiny stool and table bolted to the wall, trying to ignore the discomfort from my bleeding bedsores. Outdoor temperatures — that sometimes soared up to 120 °F — converted the cell into a concrete oven, making it difficult to write without the sweat from my hands and arms moistening the paper.

Here are the first few paragraphs I wrote:

19 Feb 04

The toilet I sleep next to is full of sewage. We’ve had no running water for three days. Yesterday, I knew we were in trouble when the mound in our steel throne peaked above sea level.

Inmates often display remarkable ingenuity during difficult occasions and this crisis has resulted in a number of my neighbours defecating in the plastic bags the mouldy breakfast bread is served in. For hours they kept those bags in their cells, then disposed of them downstairs when allowed out for showers. As I write, inmates brandishing plastic bags are going from cell door to door proudly displaying their accomplishments.

The whole building reeks like a giant Portaloo. Putting a towel over the toilet in our tiny cell offers little reprieve. My neighbour, Eduardo, is suffering diarrhoea from the rotten chow. I can’t imagine how bad his cell stinks.

I am hearing that the local Health Department has been contacted. Hopefully they will come to our rescue soon.

Fearing reprisals from guards notorious for murdering prisoners, I wrote under the pseudonym Jon. As the mail officer could inspect outgoing letters, posting my words was too risky. To get my words out undetected by the staff, I employed my aunt.

She visited every week, and I was allowed to release property to her, such as mail I’d received, legal papers, and books I’d read. The visitation staff’s chief concern was stopping incoming contraband such as drugs and tobacco, so they never thoroughly examined outgoing property.

I hid my words in the property I released to my aunt. She smuggled them out of the jail, typed them up and emailed them to my parents who posted them to the Internet. Considering the time involved in maintaining a blog, I was lucky to have such outside help.

That’s how Jon’s Jail Journal came about. It was one of the first prison blogs, and went on to attract international media attention after excerpts were published in The Guardian.

After serving almost six years for money laundering and drugs, I’m now a free man. I’ve kept Jon’s Jail Journal going, so the friends I made inside can share their stories.

Like most prisoners, those in Arizona do not have Internet access. To get their writing online, they need outside help. Unfortunately, most of them do not have family members willing to run a blog for them.

I started Jon’s Jail Journal unaware Arizona had been the first state to censor its prisoners from the Internet. This came about after the widow of a murder victim read an online pen-pal ad in which her husband’s murderer described himself as a kind-hearted lover of cats. A law passed in 2000 carried penalties for prisoners writing for the Internet. Privileges could be taken away, sentences lengthened.

The freedom to speak without censorship or limitation is guaranteed by the First Amendment, so the ACLU stepped in and challenged this law. In May 2003, Judge Earl Carroll declared the law unconstitutional. Since then, no other state has attempted to introduce such a law.

But even with that law repealed, any inmate writing openly about prison is running the risk of reprisals from the staff and the prisoners. The threat of being harmed or killed by your custodians or neighbours is a strong form of censorship.

I always got permission from the prisoners I wrote about. I hate to think of the consequences if I hadn’t. But even with that safeguard in place, I still ran into occasional problems.

I once wrote about how the prisoners made syringes from commissary items. A prisoner received a copy of that blog in the mail, and circulated it on the yard. Some of the older white gang members gave the order to have me smashed, claiming they were concerned the staff would read that blog and stop the inmate store from selling the items the prisoners needed to make the syringes.

Fortunately, I was writing stories about some well-established prisoners at the time. Like Two Tonys, a Mafia associate classified as a mass murderer. Frankie, a Mexican Mafia hitman. C-Ducc, a Crip with one of the toughest reputations on the yard. They intervened, pointing out that the staff were well aware of how the prisoners made syringes, and that I hadn’t divulged anything that the staff didn’t already know about. After a few tense days during which they instructed me not to walk the yard alone, the matter died down.

To avoid conflict with the administration, I never used real staff or prisoner names. Using real names would have enabled the administration to classify me as a threat to the security of the institution. If you are deemed such a threat, the administration can invoke laws that strip you of your standard human rights. You can lose your privileges, be housed in the system’s darkest quarters, and if the staff really have it in for you, you may suddenly receive a gorilla-sized cellmate intent on using you as his plaything.

On that front, I must credit Shannon Clark — my friend in prison who writes the blog Persevering Prison Pages — for being a much braver man than I. He has sprinkled guards’ names liberally throughout his blog, and he’s not exactly praising them for their humanity. Shannon has a reputation for being fast to slap lawsuits on the staff, which I hope continues to protect him from major retaliation.

After my release in December 2007, I figured my censorship battles with the Arizona Department of Corrections were over. I was maintaining the blog mostly for the stories of the friends I’d made inside, stories they were mailing to me in England. But in August 2008, I stopped receiving mail from them. Then in September, I received a disturbing email:

I wanted to let you know that *** called me today with a message for you. I guess the prison spoke to all of the guys that write to you and told them they are not allowed to write to you anymore. He thinks it’s because they (the prison) don’t like what is being said on your blog. It is a free country isn’t it? Can they do that? It’s ridiculous!

Attempting to sabotage Jon’s Jail Journal, certain staff members had ordered the contributors to stop writing to me. If they continued to write to me, they would receive disciplinary sanctions such as losing their visits, phone calls, and commissary.

This violation of their freedom of speech earned me a nerve-racking live spot on Sky’s headline news. The publicity attracted a prisoners’-rights attorney, and the problem eventually went away.

With all of these obstacles, it’s unsurprising that so few prisoners are writing for the Internet.

Googling for prison bloggers, I immediately noticed the absence of women in this fledgling community. I found one writer, but she had been released. Hoping to bring the voices of women prisoners online, I wrote to two women — Renee, a lifer in America serving 60 years, and Andrea, a Scottish woman arrested for the attempted murder of her abusive boyfriend in England. I’m delighted that these two women are now regular contributors to Jon’s Jail Journal, giving their unique insights on what it’s like in women’s prisons.

To keep Jon’s Jail Journal going, I’ve had to overcome censorship from many angles, some foreseen, some unexpected. The blog has managed to survive these challenges, and to build up a loyal readership over the years. It has become a bridge to the outside world for my prisoner friends. They really enjoy the feedback from the public, and some of them receive pen pals from around the world. Through blogging, they are cultivating their own writing skills, and focusing on something positive in such a negative environment. Jon’s Jail Journal has come a long way since when I lived with the cockroaches.

Anne again here: okay, that was the before. Here is the after.

I never set out to be a writer. My sister, Karen Attwood, with her literature degree, job as a journalist, and fluency in five languages, was always the family wordsmith. At age 9, she even put together her own newspaper: “Kag’s Rags.” Before my arrest, the last novel I’d picked up was To Kill a Mockingbird — but only because it was required reading in high school. I viewed fiction as frivolous, and buried myself in books on the stock market.

Then in 2002, along came a SWAT team and a sequence of events that would send my life in a whole new direction. After breaking the law for years, I’d landed myself in the jail run by the king of pink boxer shorts: Sheriff Joe Arpaio. I was a stockbroker gone wild who’d tried to transfer the Manchester rave scene to Phoenix, Arizona, and that included bringing in drugs like Ecstasy. I was charged with money laundering and drug offences.

Letters that I sent home detailing the jail conditions led to my loved ones encouraging me to keep writing. My dad had just read The Clandestine Diary of an Ordinary Iraqi by Salam Pax, containing the blog entries Pax wrote as the bombs rained down on Baghdad. We had the idea to start a blog. Spurred on by a guard who’d told me that the world had no idea what really went on in the jail, I figured a blog might be a good way to expose the human rights violations.

Sheriff Joe Arpaio’s jail has the highest rate of death in America. The jail has paid out tens of millions to family members of the deceased. Some of whom – such as Charles Agster and Scott Norberg — died at the hands of the guards. Setting the blog up clandestinely and recruiting my aunt to smuggle out my golf-pencilled efforts right under the guards’ noses appealed to my rebellious nature.

Jon’s Jail Journal had few hits until The Guardian ran excerpts detailing my relations with the cockroaches. Other media ran stories and it gathered a following.

In 2004, I was signed up by a literary agent out of London who’d read the blog. My sister worked tirelessly with her for years. We co-authored a book. It was structured as Karen’s version of my case and the effects on our family alternating with my blog entries.

I read that reading would improve my writing, so during the almost 6 years I served, I submerged myself in literature. In 2006, I read 268 books. When I told Karen, how many books I’d read, she said, “You lucky bugger! If you weren’t in prison, you’d have a job, bills responsibilities. You’d never find the time to read so much.” It was a fantastic journey through literature, ranging from older works such as Don Quixote to novels by contemporary authors such as Don DeLillo. A lot of the books were kindly mailed to the prison by my blog readers. They filled whole shelves in the prison library.

I was released in December 2007, and finally met my agent. Over wine, we toasted to the coming success of the book, which she was going to present at the London Book Fair. But a few weeks before the fair, she was hospitalised with ovarian cancer. She was sent to her parents’ home where she died at the age of 41.

Having no experience in approaching agents and publishers, I did so unprofessionally. It was like banging my head against a wall. Each rejection made me more depressed. I’d dedicated six years to writing and was getting nowhere. But then I won a first prize in a competition my mum and Prisoners Abroad had entered on my behalf while I was still incarcerated. It was a Koestler Award. I read my story at the Southbank Centre where I met the wonderful Koestler staff. I told them about my predicament, and they suggested I apply for their mentor program, which helps prisoners pursue arts.

I once read in The New Yorker that having a mentor was the final thing a would-be author needed to get published. My mentor, Sally Hinchcliffe, embodied that statement for me. She volunteered her work, travelling from a remote part of Scotland to meet me at the British Library. When we first met, we set the goals of finding me a new agent and raising the standard of my prose to a publishable level. She advised me to start over and write my story in my own voice. She also showed me how to approach literary agents in a professional way. For breathing fire on my prose this tiny bespectacled bird-watcher was labelled “Dragon Lady” by my blog readers.

Six months later, I had a new literary agent. Without Sally working her magic, I would never have achieved so much so fast. I even blogged all of our sessions, which you can read by clicking here.

It took two more people to bring me to the publication finishing line. My literary agent, who helped restructure the book — which we’ve decided to bring out as a trilogy — and my publisher, a division of Random House, for taking a chance on this unknown prison author. I’m really grateful to all of these people and the many others for helping me get this far.

Paul Reynolds, a photographer who creates fake photos for tabloid magazines, wakes up with no idea where he is or how he got there. He can’t even recall his name. A strange man lurks nearby, breathing heavily and slowly flipping through a book. Paul hears the man’s breath, but he cannot see him. He realizes with mounting panic that his eyes no longer function.

Paul Reynolds, a photographer who creates fake photos for tabloid magazines, wakes up with no idea where he is or how he got there. He can’t even recall his name. A strange man lurks nearby, breathing heavily and slowly flipping through a book. Paul hears the man’s breath, but he cannot see him. He realizes with mounting panic that his eyes no longer function.

How can a man die twice?

How can a man die twice?

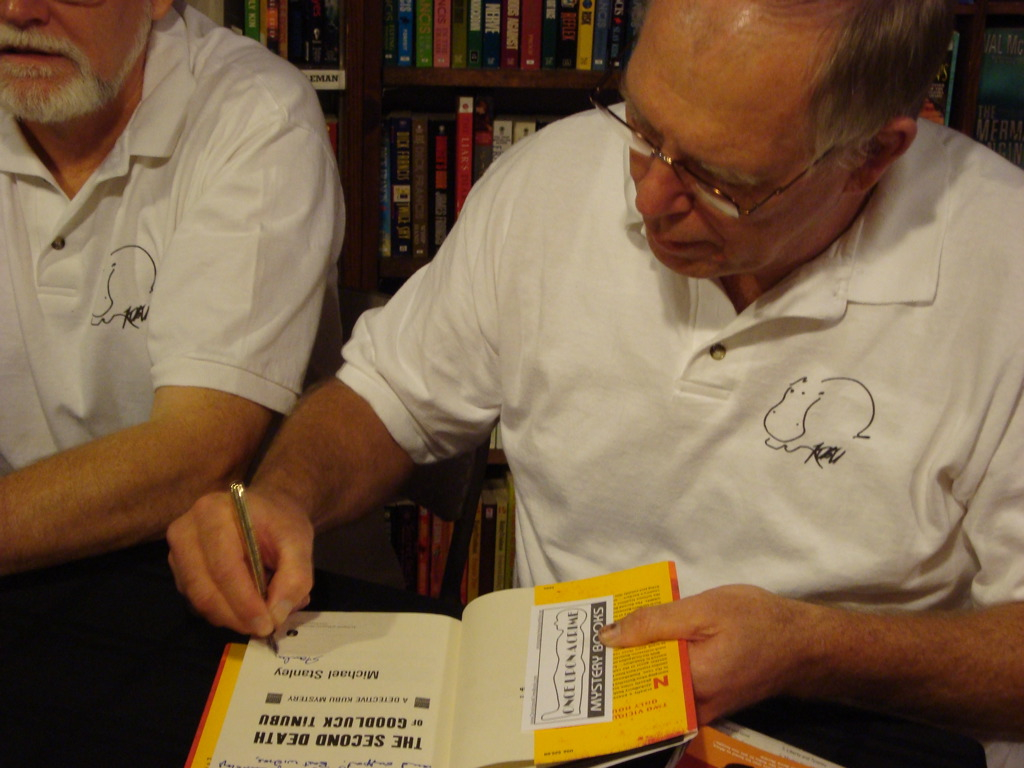

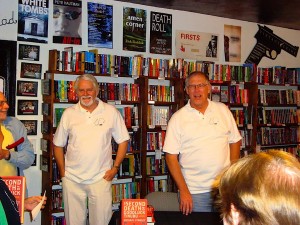

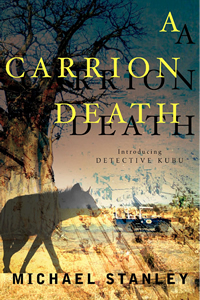

Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip.

Michael Stanley is the writing team of Michael Sears and Stanley Trollip.

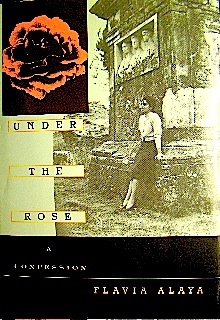

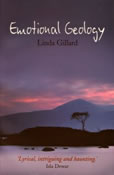

Rose Leonard is on the run from her life. Taking refuge in a remote island community, she cocoons herself in work, silence and solitude in a house by the sea. But she is haunted by her past, by memories and desires she’d hoped were long dead. Rose must decide whether she has in fact chosen a new life or just a different kind of death. Life and love are offered by new friends, her lonely daughter, and most of all Calum, a fragile younger man who has his own demons to exorcise. But does Rose, with her tenuous hold on life and sanity, have the courage to say yes to life and put her past behind her?

Rose Leonard is on the run from her life. Taking refuge in a remote island community, she cocoons herself in work, silence and solitude in a house by the sea. But she is haunted by her past, by memories and desires she’d hoped were long dead. Rose must decide whether she has in fact chosen a new life or just a different kind of death. Life and love are offered by new friends, her lonely daughter, and most of all Calum, a fragile younger man who has his own demons to exorcise. But does Rose, with her tenuous hold on life and sanity, have the courage to say yes to life and put her past behind her? ‘I think I was damned from birth,’ Flora said, staring vacantly into space. ‘Damned by my birth.’

‘I think I was damned from birth,’ Flora said, staring vacantly into space. ‘Damned by my birth.’ Blind since birth, widowed in her twenties, now lonely in her forties, Marianne Fraser lives in Edinburgh in elegant, angry anonymity with her sister, Louisa, a successful novelist. Marianne’s passionate nature finds solace and expression in music, a love she finds she shares with Keir, a man she encounters on her doorstep one winter’s night. Keir makes no concession to her condition. He is abrupt to the point of rudeness, and yet oddly kind. But can Marianne trust her feelings for this reclusive stranger who wants to take a blind woman to his island home on Skye, to ‘show’ her the stars?

Blind since birth, widowed in her twenties, now lonely in her forties, Marianne Fraser lives in Edinburgh in elegant, angry anonymity with her sister, Louisa, a successful novelist. Marianne’s passionate nature finds solace and expression in music, a love she finds she shares with Keir, a man she encounters on her doorstep one winter’s night. Keir makes no concession to her condition. He is abrupt to the point of rudeness, and yet oddly kind. But can Marianne trust her feelings for this reclusive stranger who wants to take a blind woman to his island home on Skye, to ‘show’ her the stars?

Linda Gillard studied Drama and German at Bristol University, then trained as an actress at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. Whilst under-employed at London’s National Theatre, Linda developed a sideline as a freelance journalist. She ran two careers concurrently for a while, then gave up acting to raise a family and write from home.

Linda Gillard studied Drama and German at Bristol University, then trained as an actress at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. Whilst under-employed at London’s National Theatre, Linda developed a sideline as a freelance journalist. She ran two careers concurrently for a while, then gave up acting to raise a family and write from home.

Those of you who were hanging around the Author! Author! virtual lounge may remember Stan from last year, when he was kind enough to visit with

Those of you who were hanging around the Author! Author! virtual lounge may remember Stan from last year, when he was kind enough to visit with

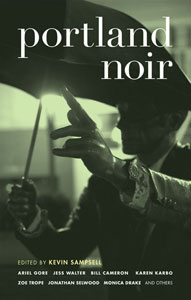

Explore the dark, rainy underbelly of one of America’s most beautiful but enigmatic cities through brand-new stories by Gigi Little, Justin Hocking, Chris A. Bolton, Jess Walter, Monica Drake, Jamie S. Rich (illustrated by Joelle Jones), Dan DeWeese, Zoe Trope, Luciana Lopez, Karen Karbo, Bill Cameron, Ariel Gore, Floyd Skloot, Megan Kruse, Kimberly Warner-Cohen, and Jonathan Selwood.

Explore the dark, rainy underbelly of one of America’s most beautiful but enigmatic cities through brand-new stories by Gigi Little, Justin Hocking, Chris A. Bolton, Jess Walter, Monica Drake, Jamie S. Rich (illustrated by Joelle Jones), Dan DeWeese, Zoe Trope, Luciana Lopez, Karen Karbo, Bill Cameron, Ariel Gore, Floyd Skloot, Megan Kruse, Kimberly Warner-Cohen, and Jonathan Selwood.

Paula Neves has been writing across genres since she was a teen, but has always loved poetry, to which she keeps returning. Her poetry has appeared in

Paula Neves has been writing across genres since she was a teen, but has always loved poetry, to which she keeps returning. Her poetry has appeared in